Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

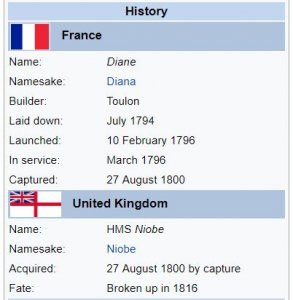

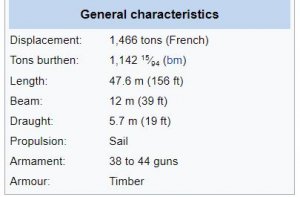

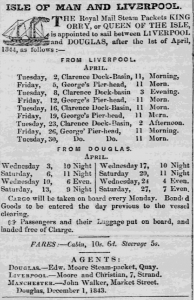

10 February 1758 – Launch of HMS Liverpool, a 28-gun Coventry-class sixth-rate frigate

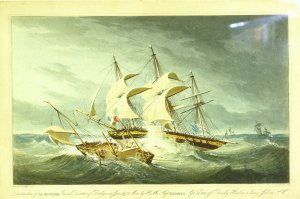

HMS Liverpool was a 28-gun Coventry-class sixth-rate frigate of the Royal Navy. Launched in 1758, she saw active service in the Seven Years' War and the American Revolutionary War. She was wrecked in Jamaica Bay, near New York, in 1778.

Construction

Liverpool was an oak-built 28-gun sixth-rate, one of 18 vessels forming part of the Coventry class of frigates. As with others in her class she was loosely modeled on the design and external dimensions of HMS Tartar, launched in 1756 and responsible for capturing five French privateers in her first twelve months at sea. The Admiralty Order to build the Coventry-class vessels was made after the outbreak of the Seven Years' War, and at a time in which the Royal Dockyards were fully engaged in constructing or fitting-out the Navy's ships of the line. Consequently, despite Navy Board misgivings about reliability and cost, contracts for all but one of Coventry-class vessels were issued to private shipyards with an emphasis on rapid completion of the task.

Contracts for Liverpool's construction were issued on 3 September 1756 to commercial shipwrights John Gorill and William Pownall. As Gorill and Pownall's shipyard was in the city of Liverpool, Admiralty determined that this would also be the name of the vessel herself. It was stipulated that work should be completed within eleven months for a 28-gun vessel measuring approximately 590 tons burthen. Subject to satisfactory completion, Gorill and Pownall would receive a modest fee of £8.7s per ton – the lowest for any Coventry-class vessel – to be paid through periodic imprests drawn against the Navy Board. Private shipyards were not subject to rigorous naval oversight, and the Admiralty therefore granted authority for "such alterations withinboard as shall be judged necessary" in order to cater for the preferences or ability of individual shipwrights, and for experimentation with internal design.

Liverpool's keel was laid down on 1 October 1756, but work proceeded slowly and the completed vessel was not ready for launch until 10 February 1758, a full six months behind schedule. As built, Liverpool was slightly longer and narrower than her sister ships in the Coventry-class, being 118 ft 4 in (36.1 m) long with a 97 ft 7 in (29.7 m) keel, a beam of 33 ft 8 in (10.26 m) and with a hold depth of 10 ft 6 in (3.2 m). Her tons burthen were measured at 589 85⁄94 tons.

Navy frigates were routinely fitted out and armed at Royal Dockyards, but Liverpool received her guns while still at the builder's yard. These comprised 24 nine-pounder cannons to be located along her gun deck, supported by four three-pounder cannons on the quarterdeck and twelve 1⁄2-pounder swivel guns ranged along her sides.

The vessel was named after the city of Liverpool in North West England. In selecting her name the Board of Admiralty continued a tradition, dating to 1644, of using geographic features; overall, ten of the nineteen Coventry-class vessels, were named after well-known regions, rivers or towns. With few exceptions the remainder of the class were named after figures from classical antiquity, following a more modern trend initiated in 1748 by John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich in his capacity as First Lord of the Admiralty.

In sailing qualities Liverpool was broadly comparable with French frigates of equivalent size, but with a shorter and sturdier hull and greater weight in her broadside guns. She was also comparatively broad-beamed which provided ample space for provisions, the ship's mess and a large magazine for powder and round shot. Taken together, these characteristics would enable Liverpool to remain at sea for long periods without resupply. She was also built with broad and heavy masts, which balanced the weight of her hull, improved stability in rough weather and made her capable of carrying a greater quantity of sail. The disadvantages of this comparatively heavy design were a decline in manoeuvrability and slower speed when sailing in light winds.

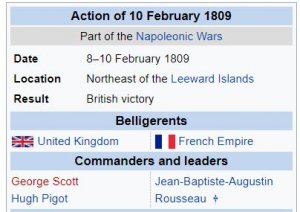

Her designated complement was 200, comprising two commissioned officers – a captain and a lieutenant – overseeing 40 warrant and petty officers, 91 naval ratings, 38 Marines and 29 servants and other ranks. Among these other ranks were four positions reserved for widow's men – fictitious crew members whose pay was intended to be reallocated to the families of sailors who died at sea.

Seven Years' War

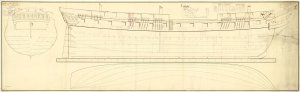

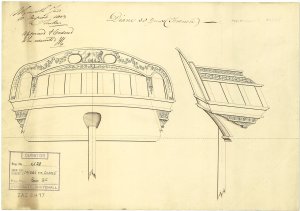

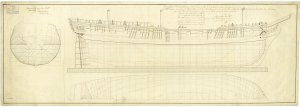

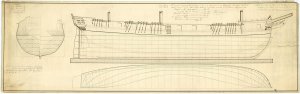

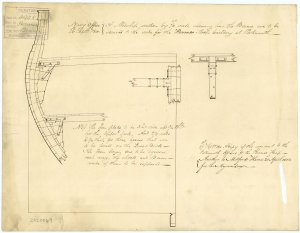

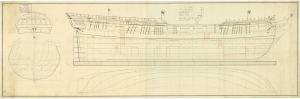

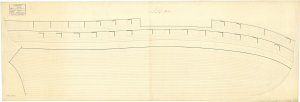

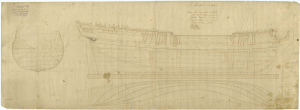

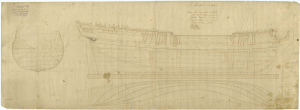

Plan showing the body plan, sheer lines with inboard detail and longitudinal half breadth as proposed for the Liverpool, 1756

Liverpool was launched on 10 February 1758 and immediately commissioned into the Navy under the command of Captain Richard Knight. After taking on her crew, she was assigned to the Royal Navy squadron patrolling the English Channel near Dunkirk, on watch for French vessels seeking to prey on British merchant shipping. On 11 May 1759 Levant captured L'Emerillon, an 8-gun French privateer. The vessel and her 52 crew were subsequently delivered to British authorities at Yarmouth. Two further victories followed, with the capture of La Nouvelle Hirondelle on 7 July and Le Glaneur on 20 November.

In March 1760 she was reassigned to convoy protection duties, between Britain and colonial outposts in the East Indies and North America. After two years she was again reassigned, as a support vessel for the Royal Navy's loose blockade of the port of Brest. In this role Liverpool was responsible for carrying messages between the blockading ships, and watching for French attempts to leave port. On 25 April 1762, while still engaged in these duties, the frigate encountered and overwhelmed Le Grand Admiral, a privateer from Bayonne. This was Richard Knight's last engagement as captain of Liverpool; in June 1762 he surrendered his command and returned to England. In Knight's absence, Liverpool secured her fifth victory at sea with the capture of French privateer Le Jacques.

Liverpool's captaincy was filled in September with the appointment of Edward Clark, formerly the first lieutenant of the 14-gun sloop HMS Fortune. War with France was drawing to a close, and by January 1763 negotiations were well advanced for the peace settlement that would be finalised in the Treaty of Paris. On 20 January 1763 Clark was ordered to sail for the East Indies with news of imminent peace. Captain Clarke committed suicide in March 1764, during Liverpool's return voyage. On reaching England, the frigate was declared surplus to the Navy's peacetime requirements, and taken to Woolwich Dockyard for decommissioning.

Inter-war period

Liverpool underwent a "great repair" between March 1766 and April 1767, and was re-commissioned in March 1767. She was subsequently ordered to Newfoundland. After two years service there, she journeyed to the Mediterranean, remaining there until her eventual return for paying off in Chatham, England in March 1772.

American Revolutionary War

Liverpool was re-commissioned in July 1775, shortly after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War. Command was given to Captain Henry Bellew, with the frigate setting sail for North America on 14 September. On 26 August 1776 she was on patrol off Nova Scotia when she encountered two rebel schooners, USS Warren and USS Lynch. The American vessels fled in separate directions, with Bellew electing to follow Warren. After a short chase the American schooner was overhauled and captured; she was transformed into a ship's tender for Liverpool and her crew kept under guard until September when they were transferred to HMS Milford along with Warren's guns.

In 1777, Liverpool was added to a fleet under the overall command of Viscount Howe. On 11 February 1778, she was wrecked in Jamaica Bay, Long Island.

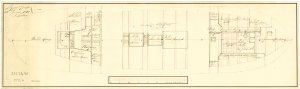

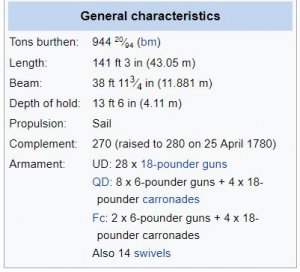

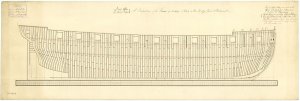

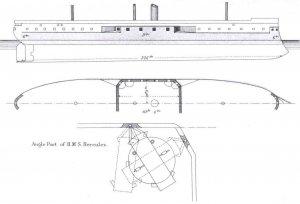

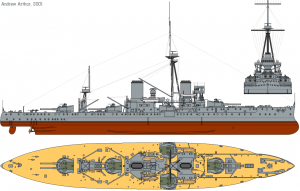

Scale 1:48. Plan showing the body plan, sheer lines with inboard detail, longitudinal half breadth for Coventry (1757), Lizard (1757),Liverpool (1757), Maidstone (1758), Acteon (1757), Shannon (1757), Levant (1757), Coberus (1757), Griffin (1757), Hussar (1757), all 28-gun, Sixth Rate Frigates, based on the plan for Lowestoft (1756) and Tartar (1756, which were the same as Unicorn (1748) and Lyme (1748). Maidstone (1758), Cerberus (1757), Griffin (1757), Acteon (1757), Shannon (1757),Bureas (1757) and Trent (1757) had the House holes moved to the upper deck. There are construction amendments for the first built Frigates. Annoted in the top right: " Body, same as the Lestaff and Tartar, except one havng a Beakhead and the other a round bow, withou the least alteration below the surface of the water - and the Tartar and Leostaff are exactly the same Body as the Unicorn and Lime. "

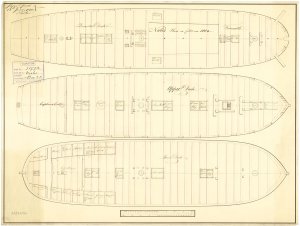

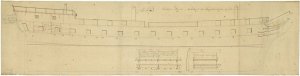

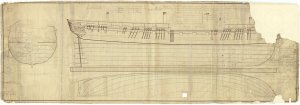

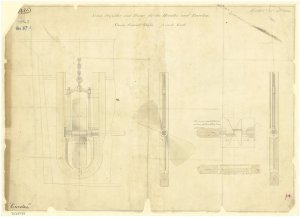

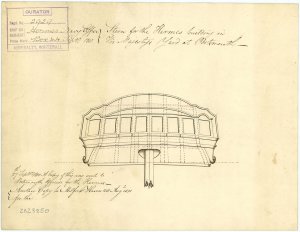

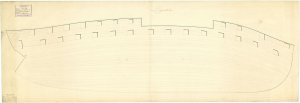

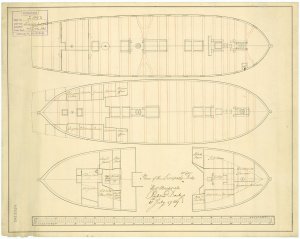

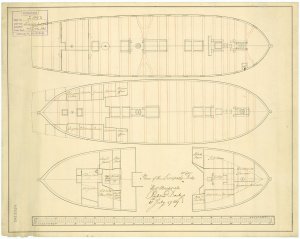

Scale 1:48. Plan showing the upper deck, lower deck and fore & aft platforms as proposed for Liverpool (1758), a 28-gun, Sixth Rate Frigate.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Liverpool_(1758)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coventry-class_frigate

https://collections.rmg.co.uk/colle...el-326411;browseBy=vessel;vesselFacetLetter=L

10 February 1758 – Launch of HMS Liverpool, a 28-gun Coventry-class sixth-rate frigate

HMS Liverpool was a 28-gun Coventry-class sixth-rate frigate of the Royal Navy. Launched in 1758, she saw active service in the Seven Years' War and the American Revolutionary War. She was wrecked in Jamaica Bay, near New York, in 1778.

Construction

Liverpool was an oak-built 28-gun sixth-rate, one of 18 vessels forming part of the Coventry class of frigates. As with others in her class she was loosely modeled on the design and external dimensions of HMS Tartar, launched in 1756 and responsible for capturing five French privateers in her first twelve months at sea. The Admiralty Order to build the Coventry-class vessels was made after the outbreak of the Seven Years' War, and at a time in which the Royal Dockyards were fully engaged in constructing or fitting-out the Navy's ships of the line. Consequently, despite Navy Board misgivings about reliability and cost, contracts for all but one of Coventry-class vessels were issued to private shipyards with an emphasis on rapid completion of the task.

Contracts for Liverpool's construction were issued on 3 September 1756 to commercial shipwrights John Gorill and William Pownall. As Gorill and Pownall's shipyard was in the city of Liverpool, Admiralty determined that this would also be the name of the vessel herself. It was stipulated that work should be completed within eleven months for a 28-gun vessel measuring approximately 590 tons burthen. Subject to satisfactory completion, Gorill and Pownall would receive a modest fee of £8.7s per ton – the lowest for any Coventry-class vessel – to be paid through periodic imprests drawn against the Navy Board. Private shipyards were not subject to rigorous naval oversight, and the Admiralty therefore granted authority for "such alterations withinboard as shall be judged necessary" in order to cater for the preferences or ability of individual shipwrights, and for experimentation with internal design.

Liverpool's keel was laid down on 1 October 1756, but work proceeded slowly and the completed vessel was not ready for launch until 10 February 1758, a full six months behind schedule. As built, Liverpool was slightly longer and narrower than her sister ships in the Coventry-class, being 118 ft 4 in (36.1 m) long with a 97 ft 7 in (29.7 m) keel, a beam of 33 ft 8 in (10.26 m) and with a hold depth of 10 ft 6 in (3.2 m). Her tons burthen were measured at 589 85⁄94 tons.

Navy frigates were routinely fitted out and armed at Royal Dockyards, but Liverpool received her guns while still at the builder's yard. These comprised 24 nine-pounder cannons to be located along her gun deck, supported by four three-pounder cannons on the quarterdeck and twelve 1⁄2-pounder swivel guns ranged along her sides.

The vessel was named after the city of Liverpool in North West England. In selecting her name the Board of Admiralty continued a tradition, dating to 1644, of using geographic features; overall, ten of the nineteen Coventry-class vessels, were named after well-known regions, rivers or towns. With few exceptions the remainder of the class were named after figures from classical antiquity, following a more modern trend initiated in 1748 by John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich in his capacity as First Lord of the Admiralty.

In sailing qualities Liverpool was broadly comparable with French frigates of equivalent size, but with a shorter and sturdier hull and greater weight in her broadside guns. She was also comparatively broad-beamed which provided ample space for provisions, the ship's mess and a large magazine for powder and round shot. Taken together, these characteristics would enable Liverpool to remain at sea for long periods without resupply. She was also built with broad and heavy masts, which balanced the weight of her hull, improved stability in rough weather and made her capable of carrying a greater quantity of sail. The disadvantages of this comparatively heavy design were a decline in manoeuvrability and slower speed when sailing in light winds.

Her designated complement was 200, comprising two commissioned officers – a captain and a lieutenant – overseeing 40 warrant and petty officers, 91 naval ratings, 38 Marines and 29 servants and other ranks. Among these other ranks were four positions reserved for widow's men – fictitious crew members whose pay was intended to be reallocated to the families of sailors who died at sea.

Seven Years' War

Plan showing the body plan, sheer lines with inboard detail and longitudinal half breadth as proposed for the Liverpool, 1756

Liverpool was launched on 10 February 1758 and immediately commissioned into the Navy under the command of Captain Richard Knight. After taking on her crew, she was assigned to the Royal Navy squadron patrolling the English Channel near Dunkirk, on watch for French vessels seeking to prey on British merchant shipping. On 11 May 1759 Levant captured L'Emerillon, an 8-gun French privateer. The vessel and her 52 crew were subsequently delivered to British authorities at Yarmouth. Two further victories followed, with the capture of La Nouvelle Hirondelle on 7 July and Le Glaneur on 20 November.

In March 1760 she was reassigned to convoy protection duties, between Britain and colonial outposts in the East Indies and North America. After two years she was again reassigned, as a support vessel for the Royal Navy's loose blockade of the port of Brest. In this role Liverpool was responsible for carrying messages between the blockading ships, and watching for French attempts to leave port. On 25 April 1762, while still engaged in these duties, the frigate encountered and overwhelmed Le Grand Admiral, a privateer from Bayonne. This was Richard Knight's last engagement as captain of Liverpool; in June 1762 he surrendered his command and returned to England. In Knight's absence, Liverpool secured her fifth victory at sea with the capture of French privateer Le Jacques.

Liverpool's captaincy was filled in September with the appointment of Edward Clark, formerly the first lieutenant of the 14-gun sloop HMS Fortune. War with France was drawing to a close, and by January 1763 negotiations were well advanced for the peace settlement that would be finalised in the Treaty of Paris. On 20 January 1763 Clark was ordered to sail for the East Indies with news of imminent peace. Captain Clarke committed suicide in March 1764, during Liverpool's return voyage. On reaching England, the frigate was declared surplus to the Navy's peacetime requirements, and taken to Woolwich Dockyard for decommissioning.

Inter-war period

Liverpool underwent a "great repair" between March 1766 and April 1767, and was re-commissioned in March 1767. She was subsequently ordered to Newfoundland. After two years service there, she journeyed to the Mediterranean, remaining there until her eventual return for paying off in Chatham, England in March 1772.

American Revolutionary War

Liverpool was re-commissioned in July 1775, shortly after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War. Command was given to Captain Henry Bellew, with the frigate setting sail for North America on 14 September. On 26 August 1776 she was on patrol off Nova Scotia when she encountered two rebel schooners, USS Warren and USS Lynch. The American vessels fled in separate directions, with Bellew electing to follow Warren. After a short chase the American schooner was overhauled and captured; she was transformed into a ship's tender for Liverpool and her crew kept under guard until September when they were transferred to HMS Milford along with Warren's guns.

In 1777, Liverpool was added to a fleet under the overall command of Viscount Howe. On 11 February 1778, she was wrecked in Jamaica Bay, Long Island.

Scale 1:48. Plan showing the body plan, sheer lines with inboard detail, longitudinal half breadth for Coventry (1757), Lizard (1757),Liverpool (1757), Maidstone (1758), Acteon (1757), Shannon (1757), Levant (1757), Coberus (1757), Griffin (1757), Hussar (1757), all 28-gun, Sixth Rate Frigates, based on the plan for Lowestoft (1756) and Tartar (1756, which were the same as Unicorn (1748) and Lyme (1748). Maidstone (1758), Cerberus (1757), Griffin (1757), Acteon (1757), Shannon (1757),Bureas (1757) and Trent (1757) had the House holes moved to the upper deck. There are construction amendments for the first built Frigates. Annoted in the top right: " Body, same as the Lestaff and Tartar, except one havng a Beakhead and the other a round bow, withou the least alteration below the surface of the water - and the Tartar and Leostaff are exactly the same Body as the Unicorn and Lime. "

Scale 1:48. Plan showing the upper deck, lower deck and fore & aft platforms as proposed for Liverpool (1758), a 28-gun, Sixth Rate Frigate.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Liverpool_(1758)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coventry-class_frigate

https://collections.rmg.co.uk/colle...el-326411;browseBy=vessel;vesselFacetLetter=L