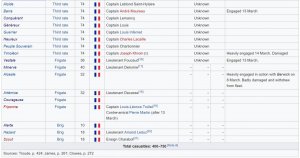

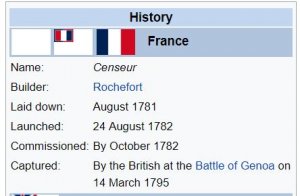

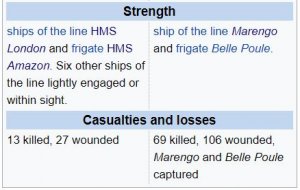

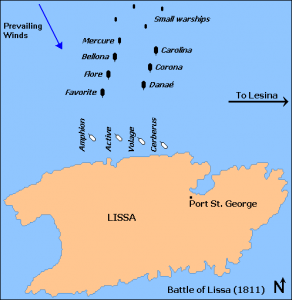

Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

13 March 1780 - HMS Alexander (74) and HMS Courageux (74), Cptn. Charles Feilding, took french Monsieur.

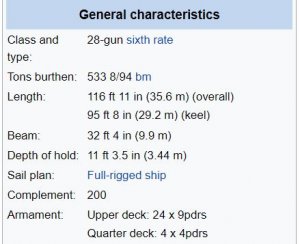

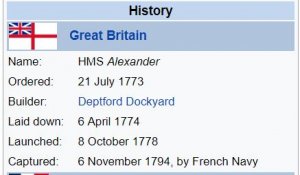

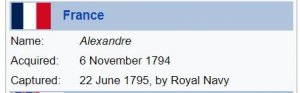

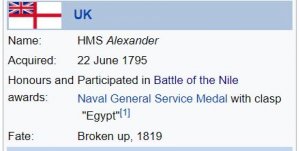

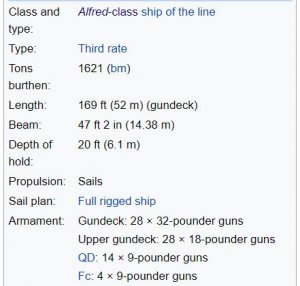

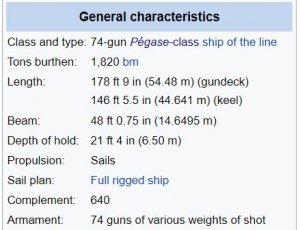

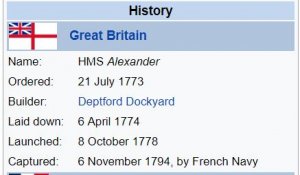

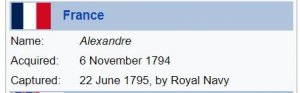

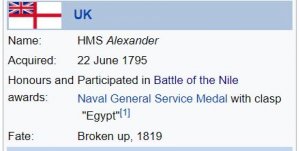

HMS Alexander was a 74-gun

third-rate of the

Royal Navy. She was launched at

Deptford Dockyard on 8 October 1778. During her career she was captured by the French, and later recaptured by the British. She fought at the Nile in 1798, and was broken up in 1819. She was named after

Alexander the Great.

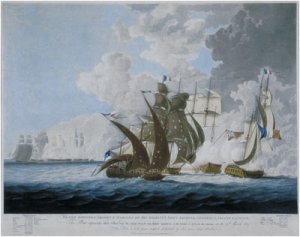

Launch of HMS

Alexander at Deptford in 1778 (BHC1875), by

John Cleveley the Younger (

NMM) - HMS

Alexander is the ship still on the

slipway, centre background

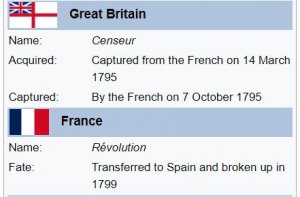

British service and capture

British service and capture

On 13 March 1780,

Alexander and

HMS Courageaux captured the 40-gun French privateer

Monsieur after a long chase and some exchange of fire. The Royal Navy took the privateer into service as

HMS Monsieur.

In 1794, whilst returning to England in the company of

HMS Canada after escorting a convoy to Spain,

Alexander, under the command of Rear-Admiral

Richard Rodney Bligh, fell in with a French squadron of five 74-gun ships, and three frigates, led by

Joseph-Marie Nielly. In the

Action of 6 November 1794 Alexander was overrun by the

Droits de l'Homme, but escaped when she damaged the

Droits de l'Homme's rigging.

Alexander was then caught by

Marat, which came behind her

stern and

raked her. Then, the 74 gun

third-rate Jean Bart closed in and fired

broadsides at close range, forcing Bligh to surrender

Alexander. In the meantime,

Canada escaped. The subsequent court martial honourably acquitted Bligh of any blame for the loss of his ship.

The French took her to Brest and then into their French Navy under the name

Alexandre. On 22 June 1795, she was with a French fleet off

Belle Île when the

Channel Fleet under

Lord Bridport discovered them. The British ships chased the French fleet, and brought them to action in the

Battle of Groix. During the battle

HMS Sans Pareil and

HMS Colossus recaptured

Alexander. After the battle,

HMS Révolutionnaire towed her back to Plymouth.

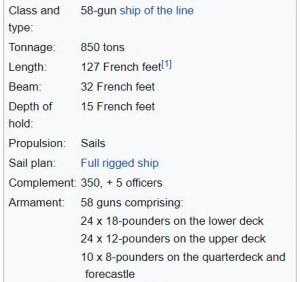

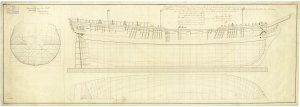

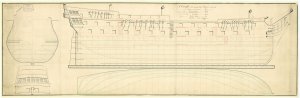

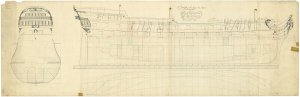

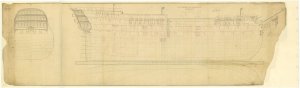

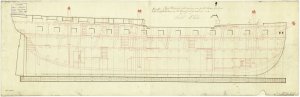

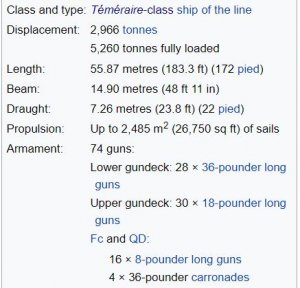

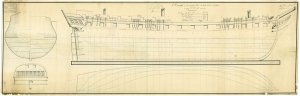

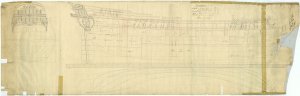

Scale: 1:48. Plan showing the body plan with stern board outline, sheer lines with inboard detail, and longitudinal half-breadth for

Alexander (1778), a 74-gun Third Rate, two-decker, as built at Deptford Dockyard.

Return to British service

The

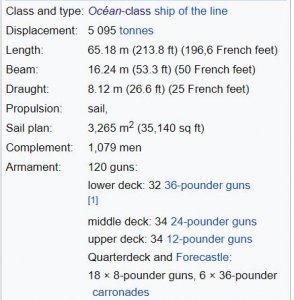

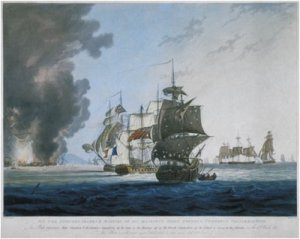

Alexander took part in the

Battle of the Nile in 1798, under the command of Captain

Alexander Ball. She was the second ship to fire upon the French fleet, engaging the flagship,

L'Orient. The

Alexander sank three French ships before she had to withdraw due to a small fire on board. The

Alexander was one of the few ships not carrying a detachment of soldiers.

Northumberland,

Alexander,

Penelope,

Bonne Citoyenne, and the brig

Vincejo shared in the proceeds of the French

polaccaVengeance, captured entering

Valletta, Malta on 6 April.

Alexander served in the navy's Egyptian campaign between 8 March 1801 and 2 September, which qualified her officers and crew for the clasp "Egypt" to the Naval General Service Medal that the

Admiralty issued in 1847 to all surviving claimants.

Fate

From 1803 she was out of commission in

Plymouth, and was finally broken up in 1819.

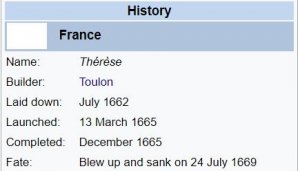

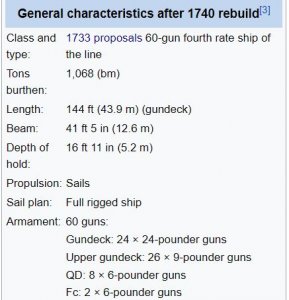

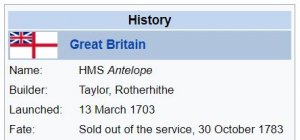

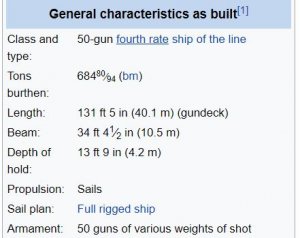

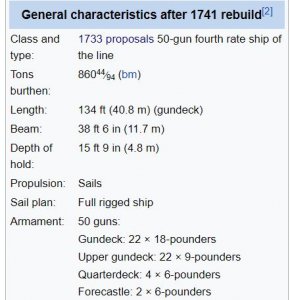

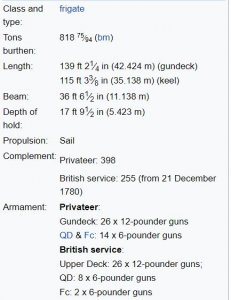

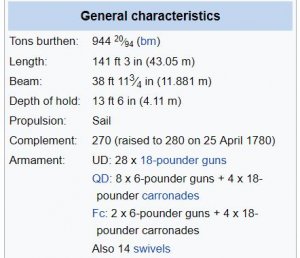

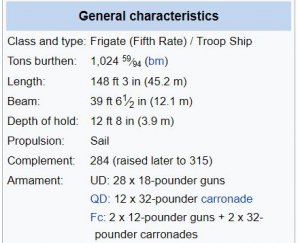

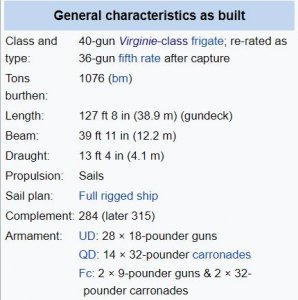

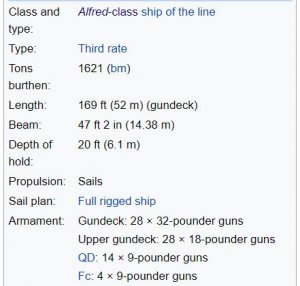

HMS Monsieur was the former 40-gun French privateer

Monsieur, built at Le Havre between July 1778 and 1779, then armed at

Granville. The

Royal Navy captured her in 1780 and subsequently put her into service as a 36-gun

Fifth Rate. This

frigate was sold in 1783.

Privateer

Privateer

From August 1779 to March 1780, Nicholas Guidelou was her captain. On her first cruise, in the space of four months, he captured 28 prizes off the English and Irish coasts. Only three of his prizes were retaken, and he brought into port 543 prisoners and 120 cannon. King

Louis XVI honoured Guidelou with a sword and a letter of thanks.

On 28 March 1779,

Monsieur captured the Scots

letter of marque Leveller, off the harbour of

Cork. Two days later, five

leaguesoff Cape Clear,

Monsieur captured the

Polly, sailing for Liverpool. After

Polly was ransomed for 1250

guineas, the privateer let her continue her journey. The next day, 1 April, another French privateer fired at

Polly, but she was able to take refuge in the port of

Skibbereen.

On 14 August 1779

John Paul Jones led a small squadron consisting of

Bon Homme Richard,

Alliance,

Pallas,

Vengeance,

Cerf, and two privateers,

Monsieur and

Granville, out of

Groa. On 18 August they recaptured the Dutch vessel

Verwagting, which an English privateer had captured eight days earlier. She had been carrying brandy and wine from Barcelona to Dunkirk. During the night

Monsieur's captain took what he wanted from the prize, and then sent her off to Ostend under his name and with his prize crew. Jones overhauled the prize, put his own prize crew aboard, and sent her off to

Lorient under his orders. The next evening

Monsieur left Jones's squadron.

Granville left either at the same time or soon thereafter.

On 22 January 1780, the

Lively was sailing from London to Liverpool when she fell victim to the Irish pirate vessel

Black Prince.

Lively escaped only to fall victim to

Monsieur two days later.

Monsieur took all the crew out of

Lively, except for three boys, and put a 13-man prize crew aboard. On 4 February, the boys recaptured the ship while almost the entire prize crew was asleep. The next day they sailed to

Kinsale where the

letter of marque Hercules took possession.

Capture

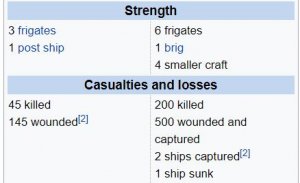

On 12 March 1780 the

Third Rate Alexander, under the command of Captain

Lord Longford, was west of

Scilly when she spotted a frigate.

Alexander gave chase and after 18 hours got within range, at which time the quarry raised French colours. The two vessels exchanged fire for some two hours, the quarry using stern chasers to answer

Alexander's bow chasers. As

Alexander pulled alongside the quarry,

Alexander's fore-top-mast simply fell over due to rot. Fortunately,

Courageux, Captain Charles Fielding, had joined the engagement and she took up the chase. Some time and some firing later, the quarry

struck. She turned out to be the

Monsieur, of

Granville, under the command of Jean de Bochet. She was armed with 40 guns, 12-pounders on the gundeck and 6-pounders on the quarterdeck and forecastle, and had a crew of 362 men. She was eight days out of Lorient but had taken no prizes. Longford described her as "a very fine frigate, almost new".

British service

The prize was brought into

Portsmouth harbour on 19 March, a week after her capture, and the Admiralty decided to take her into service. She was refitted for Royal Naval service at a cost of £8,364 between May and October 1780, and re-armed as a 36-gun frigate.

The Royal Navy commissioned her as HMS

Monsieur under the command of Captain

the Honourable Charles Phipps in July 1780. On 10 December,

Monsieur, in company with

Vestal,

St Albans,

Portland, and

Solebay captured

Comtess de Buzancois. A few days later, on 15 December,

Monsieur captured the French cutter

Chevreuil.

Chevreuil, of

Saint-Malo, was armed with twenty 6-pounder guns, had a crew of 116 men, and had been launched on 1 March 1779.

In 1781,

Monsieur, now commanded by Captain the Honourable Seymour Finch, was serving with Vice-Admiral

Darby's Channel Fleet. She therefore participated in the

relief of Gibraltar, with the fleet sailing from Spithead on 13 March and arriving at Gibraltar on 12 April. At some point, vessels of the Fleet engaged Spanish

gunboats off Cadiz, during which

Monsieur and

Minerva had some men badly wounded.

Monsieur was among the many ships of Darby's fleet that shared in the prize money for the capture of

Duc de Chartres, the Spanish frigate

Santa Leocadia, and the French brig

Trois Amis.

On 9 October 1781,

Monsieur,

Minerva, Captain Charles Fielding,

Flora and

Crocodile captured the American privateer

Hercules, of 20 guns and 120 men. The next day

Minervaand

Monsieur captured the American privateer

Jason, of 22 guns.

Minerva captured the privateer

Wexford, which was six weeks out of Boston and had captured nothing. All three privateers were taken off

Cape Clear Island, Ireland, and taken into

Cork.

On 12 December at the

Second Battle of Ushant, Admiral

Richard Kempenfelt captured 15 French transports.

Monsieur was among the many vessels that shared in the prize money for the

Emille Sophie de Brest and the

Margueritte, and presumably other prizes.

In the middle of July 1782,

Monsieur was in a squadron of four

third rates and three frigates under the command of Captain Reeve, in the recently launched

Crown, as commodore. In the Bay of Biscay the squadron captured three prizes: the

Pigmy cutter, the

Hermione, a victualler with 90 bullocks for the combined fleet, and a brig carrying salt.

Fate

Following the conclusion of the war,

Monsieur was paid off at Deptford in March 1783. She was sold for £820 on 25 September of that year.

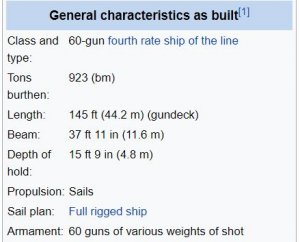

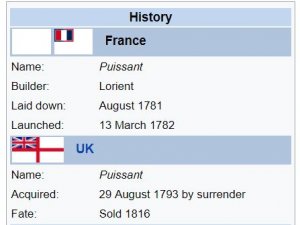

Courageux was a heavy 74-gun

ship-of-the-line of the

French Navy, launched in 1753. She was captured by the Royal Navy in 1761 and taken into service as

HMS Courageux. In 1778, she joined the

Channel Fleet and later, was part of the squadron commanded by

Commodore Charles Fielding, that controversially captured a Dutch convoy on 31 December 1779, in what became known as the

Affair of Fielding and Bylandt. On 4 January 1781,

Courageux was west of

Ushant, when she recaptured

Minerva in a close range action that lasted more than an hour. The following Spring,

Courageux joined the convoy, under

George Darby, which successfully relieved the besieged

Gibraltar.

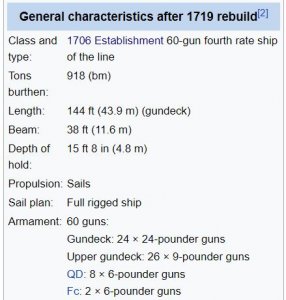

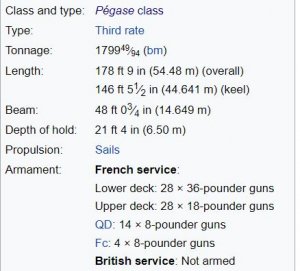

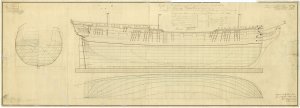

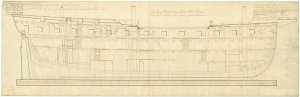

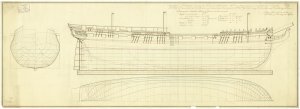

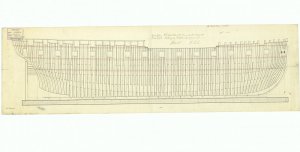

Scale: 1:48. Plan showing the body plan with stern board decoration and name in a cartouche on the counter, the sheer lines with inboard detail and figurehead, and the longitudinal half-breadth for

'Courageux' (1761), a captured French Third Rate, as taken off prior to fitting as a 74-gun Third Rate, two-decker at Portsmouth Dockyard.

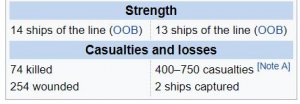

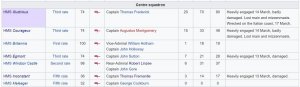

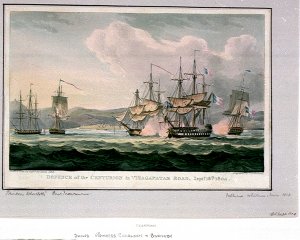

At the start of

French Revolutionary War,

Courageux took part in the blockade and subsequent occupation of

Toulon. In September 1793, she was sent with a squadron under

Robert Linzee, to support an insurrection in

Corsica and took part in the unsuccessful attack on

San Fiorenzo. When Toulon was evacuated,

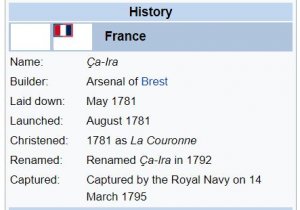

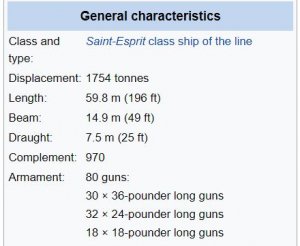

Courageux was in a state of disrepair and was forced to warp out of her mooring without a rudder. She was however able to complete repairs while she rescued allied troops from the waterfront. At the

Battle of Genoa in March 1795, she was instrumental in the capture of the French ships

Ça Ira and

Censeur but at the subsequent

Battle of the Hyères Islands, she was so slow getting into the action that by the time she arrived, the order had been given to disengage.

In December 1796,

Courageux was with the

Mediterranean fleet, anchored in the bay of Gibraltar, when a great storm tore her from her mooring and drove her onto the rocks of the

Barbary coast. Of the 593 officers and men that were on board, only 129 escaped; five by means of a launch, and the rest by clambering along the fallen mainmast to the shore.

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org