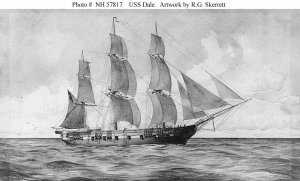

Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

14 December 1907 – The Thomas W. Lawson, the largest ever ship without a heat engine, runs aground and founders near the Hellweather's Reef within the Isles of Scilly in a gale. The pilot and 15 seamen die.

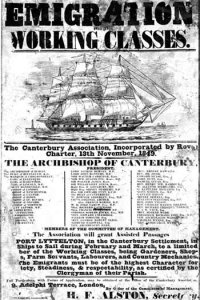

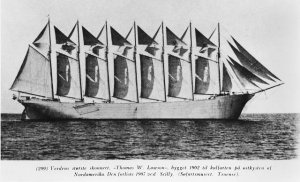

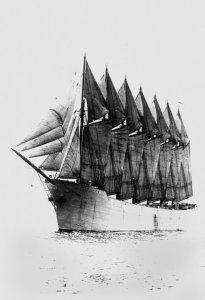

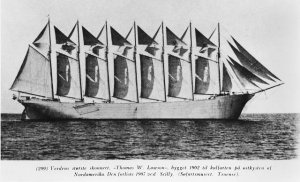

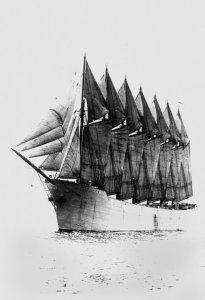

Thomas W. Lawson was a seven-masted, steel-hulled schooner built for the Pacific trade, but used primarily to haul coal and oil along the East Coast of the United States. Named for copper baron Thomas W. Lawson, a Boston millionaire, stock-broker, book author, and President of the Boston Bay State Gas Co., she was launched in 1902 as the largest schooner and largest sailing vessel without an auxiliary engine ever built.

Thomas W. Lawson was destroyed off the uninhabited island of Annet, in the Isles of Scilly, in a storm on December 14, 1907, killing all but two of her eighteen crew and a harbor pilot already aboard. Her cargo of 58,000 barrels of light paraffin oil caused perhaps the first large marine oil spill.

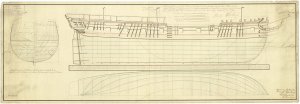

Development and construction

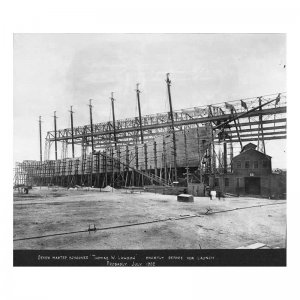

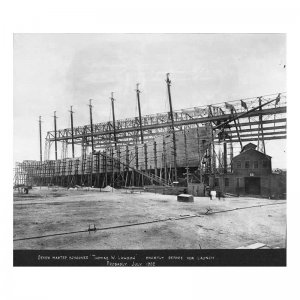

Designed by naval architect Bowdoin B. Crowninshield (famous for his fast yachts) for Captain John G. Crowley of the Coastwise Transportation Company of Boston, Massachusetts, the construction of Thomas W. Lawson was contracted to the Fore River Ship and Engine Company on June 25, 1901. At a cost of approximately $250,000, she was the only seven-masted schooner, the only seven-masted sailing ship in modern time (see Zheng He's Treasure Ships), the largest schooner, and the largest pure sailing vessel, in terms of tonnage, ever built. Larger sailing vessels with auxiliary engines for propulsion were the French France II (1911) and German R. C. Rickmers (1906), both five-masted barques.

Thomas W. Lawson's design and purpose was an ultimately unsuccessful bid to keep sailing ships competitive with the burgeoning steamship freight transport trade. However the ship's submerged hull was too large and sail area too small for good sailing properties; compounded by a forced reduction in load capacity from 11,000 to 7,400 long tons that made “working to capacity” impossible, the combination undermined expected profits.

Class and type:

Displacement: 13,860 ts (at 11,000 ts load); 10,260 ts (at 7,400 ts load)

Length:

Height:

Draft:

Depth of hold: 32 ft (9.8 m)

Decks: 2 continuous steel decks, poop and forecastle decks

Installed power: no auxiliary propulsion; donkey engine for sail winches, steam rudder, generator

Propulsion: wind

Sail plan: 25 sails: 7 gaff main sails (No. 1 to 6 of equal size, spanker sail of larger size), 7 gaff topsails, 6 staysails, 5 foresails with 43.000 sq ft (4,000 m²) [46,617 sq ft (4,330.86 m²)] sail area

Speed: 16 knots (29.632 km/h)

Boats & landing craft carried: three lifeboats and captain's gig (stern)

Complement: 1902: 16: 1907: 18

Crew: 1902: 16; 1907: 18 (captain, engineer, 2 stewards, two helmsmen (1st & 2nd mates), 10 to 12 able seamen)

Launched on July 10, 1902, Thomas W. Lawson was 475 ft (145 m) overall, 395 feet (120.4 m) on deck, and contained seven masts of equal height (193 feet (58.8 m)) which carried 25 sails (seven gaff sails, seven gaff topsails, six topmast staysails and five jib sails (fore staysail, jib, flying jib, jib topsail, balloon jib) encompassing 43,000 square feet (4,000 m²)) of canvas. Originally painted white, the ship's hull was later painted black. The naming of her masts was always a subject for some discussion (see external link "The Masts of the Thomas W. Lawson"). In the original sail plan and during construction named (fore to aft): 'no. 1 to no. 7', no. 7 being replaced by "spanker mast." The names of the masts changed then to: 'fore, main, mizzen, spanker, jigger, driver, and pusher' at launch and to: 'forecastle, fore, main, mizzen, jigger, and spanker' after launch. Different naming systems ensued, e.g. 'fore, main, mizzen, rusher, driver, jigger, and spanker' or 'fore, main, mizzen, no. 4, no. 5, no. 6, and no. 7', the naming preferred by the crew (which incorporated a possible misunderstanding between "fore" meaning "foremast" and "mast no. four"). Even a naming after the days of the week was discussed with the foremast being named "Sunday" and the spankermast "Saturday".

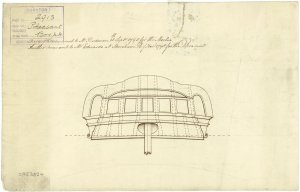

The ship consisted of a steel hull with high bulwarks and a double cellular bottom four feet deep and used 1,000 tons of water ballast. She measured 5,218 gross register tons, could carry nearly 11,000 tons of coal, and was operated by a crew of 16 to 18 including captain, engineer, two helmsmen, and two stewards. Due to the shallow depth of the eastern ports except Newport , VA, she could not enter them with her maximum load. As a result, she carried a reduced capacity of 7,400 tons in order to reduce her working draft. She had two continuous decks, poop and forecastle decks, a large superstructure on the poop deck including the captain's rooms with fine furniture and leather seats, the officers' mess and rooms, card room, and a separate rudder house. On the main deck were two deckhouses around mast no. 5 and behind mast no. 6, as well as six main hatches to access the holds between the masts. Two huge steam winches were built in under the forecastle and behind mast no. 6. on the main deck. Smaller electrically driven winches were installed beside each mast. The exhaust for the donkey engine boiler was horizontally installed. All seven lower steel masts were secured by five (foremast: six) shrouds per side, the wooden topmasts with four shrouds per side to the crosstrees. The two ship's stockless anchors weighed five tons each.

, VA, she could not enter them with her maximum load. As a result, she carried a reduced capacity of 7,400 tons in order to reduce her working draft. She had two continuous decks, poop and forecastle decks, a large superstructure on the poop deck including the captain's rooms with fine furniture and leather seats, the officers' mess and rooms, card room, and a separate rudder house. On the main deck were two deckhouses around mast no. 5 and behind mast no. 6, as well as six main hatches to access the holds between the masts. Two huge steam winches were built in under the forecastle and behind mast no. 6. on the main deck. Smaller electrically driven winches were installed beside each mast. The exhaust for the donkey engine boiler was horizontally installed. All seven lower steel masts were secured by five (foremast: six) shrouds per side, the wooden topmasts with four shrouds per side to the crosstrees. The two ship's stockless anchors weighed five tons each.

Service

Deeply loaded in Boston Harbor, hull painted in black; photo taken in 1906 or 1907

Often criticized by marine writers (and some seamen) and considered difficult to maneuver and sluggish (comparisons to a "bath tub" and a "beached whale" were made), Thomas W. Lawson proved problematic in the ports she was intended to operate in due to the amount of water she displaced. She tended to yaw and needed a strong wind to be held on course. Originally built for the Pacifictrade, the schooner was used as collier along the American East Coast. A year later in 1903, Crowley withdrew her from the coal trade. He had the topmasts, gaff booms and all other wooden sparsremoved and had chartered her out as a sea-going barge for the transportation of case oil. In 1906, she was retrofitted for sail at the Newport Shipbuilding and Drydock Company for use as a bulk oil carrier using the lower steel masts to vent oil gasses from the holds. Her capacity was 60,000 barrels. Under charter to Sun Oil Company, she was the world's first pure sailing tanker, carrying bulk oil from Texas to the eastern seaboard.

Shipbuilding and Drydock Company for use as a bulk oil carrier using the lower steel masts to vent oil gasses from the holds. Her capacity was 60,000 barrels. Under charter to Sun Oil Company, she was the world's first pure sailing tanker, carrying bulk oil from Texas to the eastern seaboard.

Wreck

Thomas W. Lawson

In 1907, Thomas W. Lawson was under charter to the Anglo-American Oil Company (part of Standard Oil) and set sail on November 19 from the piers of Marcus Hook Refinery (20 miles south of Philadelphia) to London with 58,000 barrels of light paraffin oil. Two days before leaving the new captain George Washington Dow had to hire six new men to the crew because six other seamen had quit their jobs due to payment problems. Those new men weren't able seamen and some didn't speak fluent English. Leaving the mouth of the Delaware River, on November 20, the large schooner set course for England under fair weather conditions. But the following day the weather turned considerably worse. The ship was not sighted for more than 20 days during its first transatlantic journey which was quite horrible in extremely stormy weather. With the loss of most of her sails, all but one lifeboat, and the breach of hatch no. 6, causing the ship's pumps to clog due to a mixture of intruding seawater and the engine's coal in the ship's hold, the schooner reached the Celtic Sea north west of the Isles of Scilly. On December 13, entering the English Channel, she mistakenly passed inside the Bishop Rock lighthouse, the westernmost one in Europe, and her captain anchored between the Nundeeps shallows and Gunner's Rock, north-west of the island of Annet, to ride out an impending gale, refusing several requests of St. Agnes and St. Mary's lifeboat crews to abandon the ship. Captain Dow trusting in his anchors only accepted the Trinity House pilot Billy "Cook" Hicks from St. Agnes lifeboat who came aboard at 5 p.m. on Friday 13. Both lifeboats of St. Agnes and St. Mary's had to return to their stations because of an unconscious crewman on the former and a broken mast on the latter. They cabled to Falmouth, Cornwall, for a tug which couldn't put to sea, unable to face the storm.

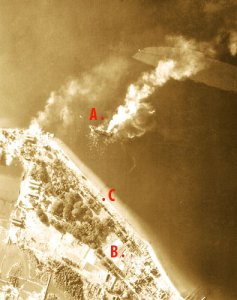

During the night around 1:15 a.m. the storm increased, her port anchor chain broke, and half an hour later the starboard anchor chain snapped close the hawsepipe. Left to the mercy of the raging seas the pounding schooner was smashed starboardside on against Shag Rock near Annet by tremendously heavy seas after having grounded on the dangerous underwater rocks. All seven masts broke off and fell into the sea with all of the seamen who had climbed the rigging for safety, on their captain's command. The stern section broke apart behind mast no. 6, drifting from the capsizing and sinking ship. In the morning light the ship's upturned keel could be seen near the reef from which the wreck slid off into deeper water. Some 16 of the 18 crew and the Scillonian pilot Wm. "Cook" Hicks who was already on board having climbed up the spanker rigging for safety were lost. Captain George W. Dow and engineer Edward L. Rowe from Boston were the only survivors, probably because they managed to get on deck from the rigging and jumped into the sea before the ship capsized. Both were lucky in being washed to a rock in the Hellweathers, to the south of the wrecking site, to be rescued hours later by the pilot's son, in the six-oared gig Slippen, looking for his father, Despite wearing their lifebelts, the other seamen died in the thick oil layer, the smashing seas, and the schooner's rigging that had drowned so many of the crew, including the pilot. Four bodies were found later - those of Mark Stenton from Brooklyn, cabin boy, of two seamen from Germany and Scandinavia, and that of a man from Nova Scotia or Maine. Furthermore, some bodies without heads, legs or arms were also found which could not be identified. They were all buried in a mass grave in St Agnes cemetery.

The broken up and scattered wreck, was relocated in 1969. The bow lies at 56 ft deep on position 49°53′38″N 06°22′55″W to the north-east of Shag Rock and the stern, with the spanker mast 400m to the south-west.[1] It can be visited by scuba divers under calm weather conditions. One of the anchors is now built into the outside wall of Bleak House, Broadstairs, the former home of Charles Dickens, and can be seen with a picture of the schooner.

Memorial

In 2008 a memorial seat was blessed by the Reverend Guy Scott in the churchyard of St Agnes, the nearest inhabitable island to the wreck and the home of the pilot, Billy "Cook" Hicks. The seat, made of granite from a St Breward quarry, faces the mass, unmarked grave of many of Thomas W. Lawson's dead

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_W._Lawson_(ship)

14 December 1907 – The Thomas W. Lawson, the largest ever ship without a heat engine, runs aground and founders near the Hellweather's Reef within the Isles of Scilly in a gale. The pilot and 15 seamen die.

Thomas W. Lawson was a seven-masted, steel-hulled schooner built for the Pacific trade, but used primarily to haul coal and oil along the East Coast of the United States. Named for copper baron Thomas W. Lawson, a Boston millionaire, stock-broker, book author, and President of the Boston Bay State Gas Co., she was launched in 1902 as the largest schooner and largest sailing vessel without an auxiliary engine ever built.

Thomas W. Lawson was destroyed off the uninhabited island of Annet, in the Isles of Scilly, in a storm on December 14, 1907, killing all but two of her eighteen crew and a harbor pilot already aboard. Her cargo of 58,000 barrels of light paraffin oil caused perhaps the first large marine oil spill.

Development and construction

Designed by naval architect Bowdoin B. Crowninshield (famous for his fast yachts) for Captain John G. Crowley of the Coastwise Transportation Company of Boston, Massachusetts, the construction of Thomas W. Lawson was contracted to the Fore River Ship and Engine Company on June 25, 1901. At a cost of approximately $250,000, she was the only seven-masted schooner, the only seven-masted sailing ship in modern time (see Zheng He's Treasure Ships), the largest schooner, and the largest pure sailing vessel, in terms of tonnage, ever built. Larger sailing vessels with auxiliary engines for propulsion were the French France II (1911) and German R. C. Rickmers (1906), both five-masted barques.

Thomas W. Lawson's design and purpose was an ultimately unsuccessful bid to keep sailing ships competitive with the burgeoning steamship freight transport trade. However the ship's submerged hull was too large and sail area too small for good sailing properties; compounded by a forced reduction in load capacity from 11,000 to 7,400 long tons that made “working to capacity” impossible, the combination undermined expected profits.

Class and type:

- seven-masted steel gaffschooner

- collier, case-oil tanker and bulk-oil carrier (1906)

Displacement: 13,860 ts (at 11,000 ts load); 10,260 ts (at 7,400 ts load)

Length:

- 475 ft (145 m) (overall)

- 394.3 ft (120.2 m) (on deck)

- 369.25 ft (112.55 m) (btw. perpendiculars)

Height:

Draft:

- 28 ft (8.5 m) at 7,400 ts

- 35.33 ft (10.77 m) at 11,000 ts

Depth of hold: 32 ft (9.8 m)

Decks: 2 continuous steel decks, poop and forecastle decks

Installed power: no auxiliary propulsion; donkey engine for sail winches, steam rudder, generator

Propulsion: wind

Sail plan: 25 sails: 7 gaff main sails (No. 1 to 6 of equal size, spanker sail of larger size), 7 gaff topsails, 6 staysails, 5 foresails with 43.000 sq ft (4,000 m²) [46,617 sq ft (4,330.86 m²)] sail area

Speed: 16 knots (29.632 km/h)

Boats & landing craft carried: three lifeboats and captain's gig (stern)

Complement: 1902: 16: 1907: 18

Crew: 1902: 16; 1907: 18 (captain, engineer, 2 stewards, two helmsmen (1st & 2nd mates), 10 to 12 able seamen)

Launched on July 10, 1902, Thomas W. Lawson was 475 ft (145 m) overall, 395 feet (120.4 m) on deck, and contained seven masts of equal height (193 feet (58.8 m)) which carried 25 sails (seven gaff sails, seven gaff topsails, six topmast staysails and five jib sails (fore staysail, jib, flying jib, jib topsail, balloon jib) encompassing 43,000 square feet (4,000 m²)) of canvas. Originally painted white, the ship's hull was later painted black. The naming of her masts was always a subject for some discussion (see external link "The Masts of the Thomas W. Lawson"). In the original sail plan and during construction named (fore to aft): 'no. 1 to no. 7', no. 7 being replaced by "spanker mast." The names of the masts changed then to: 'fore, main, mizzen, spanker, jigger, driver, and pusher' at launch and to: 'forecastle, fore, main, mizzen, jigger, and spanker' after launch. Different naming systems ensued, e.g. 'fore, main, mizzen, rusher, driver, jigger, and spanker' or 'fore, main, mizzen, no. 4, no. 5, no. 6, and no. 7', the naming preferred by the crew (which incorporated a possible misunderstanding between "fore" meaning "foremast" and "mast no. four"). Even a naming after the days of the week was discussed with the foremast being named "Sunday" and the spankermast "Saturday".

The ship consisted of a steel hull with high bulwarks and a double cellular bottom four feet deep and used 1,000 tons of water ballast. She measured 5,218 gross register tons, could carry nearly 11,000 tons of coal, and was operated by a crew of 16 to 18 including captain, engineer, two helmsmen, and two stewards. Due to the shallow depth of the eastern ports except Newport

, VA, she could not enter them with her maximum load. As a result, she carried a reduced capacity of 7,400 tons in order to reduce her working draft. She had two continuous decks, poop and forecastle decks, a large superstructure on the poop deck including the captain's rooms with fine furniture and leather seats, the officers' mess and rooms, card room, and a separate rudder house. On the main deck were two deckhouses around mast no. 5 and behind mast no. 6, as well as six main hatches to access the holds between the masts. Two huge steam winches were built in under the forecastle and behind mast no. 6. on the main deck. Smaller electrically driven winches were installed beside each mast. The exhaust for the donkey engine boiler was horizontally installed. All seven lower steel masts were secured by five (foremast: six) shrouds per side, the wooden topmasts with four shrouds per side to the crosstrees. The two ship's stockless anchors weighed five tons each.

, VA, she could not enter them with her maximum load. As a result, she carried a reduced capacity of 7,400 tons in order to reduce her working draft. She had two continuous decks, poop and forecastle decks, a large superstructure on the poop deck including the captain's rooms with fine furniture and leather seats, the officers' mess and rooms, card room, and a separate rudder house. On the main deck were two deckhouses around mast no. 5 and behind mast no. 6, as well as six main hatches to access the holds between the masts. Two huge steam winches were built in under the forecastle and behind mast no. 6. on the main deck. Smaller electrically driven winches were installed beside each mast. The exhaust for the donkey engine boiler was horizontally installed. All seven lower steel masts were secured by five (foremast: six) shrouds per side, the wooden topmasts with four shrouds per side to the crosstrees. The two ship's stockless anchors weighed five tons each.Service

Deeply loaded in Boston Harbor, hull painted in black; photo taken in 1906 or 1907

Often criticized by marine writers (and some seamen) and considered difficult to maneuver and sluggish (comparisons to a "bath tub" and a "beached whale" were made), Thomas W. Lawson proved problematic in the ports she was intended to operate in due to the amount of water she displaced. She tended to yaw and needed a strong wind to be held on course. Originally built for the Pacifictrade, the schooner was used as collier along the American East Coast. A year later in 1903, Crowley withdrew her from the coal trade. He had the topmasts, gaff booms and all other wooden sparsremoved and had chartered her out as a sea-going barge for the transportation of case oil. In 1906, she was retrofitted for sail at the Newport

Shipbuilding and Drydock Company for use as a bulk oil carrier using the lower steel masts to vent oil gasses from the holds. Her capacity was 60,000 barrels. Under charter to Sun Oil Company, she was the world's first pure sailing tanker, carrying bulk oil from Texas to the eastern seaboard.

Shipbuilding and Drydock Company for use as a bulk oil carrier using the lower steel masts to vent oil gasses from the holds. Her capacity was 60,000 barrels. Under charter to Sun Oil Company, she was the world's first pure sailing tanker, carrying bulk oil from Texas to the eastern seaboard.Wreck

Thomas W. Lawson

In 1907, Thomas W. Lawson was under charter to the Anglo-American Oil Company (part of Standard Oil) and set sail on November 19 from the piers of Marcus Hook Refinery (20 miles south of Philadelphia) to London with 58,000 barrels of light paraffin oil. Two days before leaving the new captain George Washington Dow had to hire six new men to the crew because six other seamen had quit their jobs due to payment problems. Those new men weren't able seamen and some didn't speak fluent English. Leaving the mouth of the Delaware River, on November 20, the large schooner set course for England under fair weather conditions. But the following day the weather turned considerably worse. The ship was not sighted for more than 20 days during its first transatlantic journey which was quite horrible in extremely stormy weather. With the loss of most of her sails, all but one lifeboat, and the breach of hatch no. 6, causing the ship's pumps to clog due to a mixture of intruding seawater and the engine's coal in the ship's hold, the schooner reached the Celtic Sea north west of the Isles of Scilly. On December 13, entering the English Channel, she mistakenly passed inside the Bishop Rock lighthouse, the westernmost one in Europe, and her captain anchored between the Nundeeps shallows and Gunner's Rock, north-west of the island of Annet, to ride out an impending gale, refusing several requests of St. Agnes and St. Mary's lifeboat crews to abandon the ship. Captain Dow trusting in his anchors only accepted the Trinity House pilot Billy "Cook" Hicks from St. Agnes lifeboat who came aboard at 5 p.m. on Friday 13. Both lifeboats of St. Agnes and St. Mary's had to return to their stations because of an unconscious crewman on the former and a broken mast on the latter. They cabled to Falmouth, Cornwall, for a tug which couldn't put to sea, unable to face the storm.

During the night around 1:15 a.m. the storm increased, her port anchor chain broke, and half an hour later the starboard anchor chain snapped close the hawsepipe. Left to the mercy of the raging seas the pounding schooner was smashed starboardside on against Shag Rock near Annet by tremendously heavy seas after having grounded on the dangerous underwater rocks. All seven masts broke off and fell into the sea with all of the seamen who had climbed the rigging for safety, on their captain's command. The stern section broke apart behind mast no. 6, drifting from the capsizing and sinking ship. In the morning light the ship's upturned keel could be seen near the reef from which the wreck slid off into deeper water. Some 16 of the 18 crew and the Scillonian pilot Wm. "Cook" Hicks who was already on board having climbed up the spanker rigging for safety were lost. Captain George W. Dow and engineer Edward L. Rowe from Boston were the only survivors, probably because they managed to get on deck from the rigging and jumped into the sea before the ship capsized. Both were lucky in being washed to a rock in the Hellweathers, to the south of the wrecking site, to be rescued hours later by the pilot's son, in the six-oared gig Slippen, looking for his father, Despite wearing their lifebelts, the other seamen died in the thick oil layer, the smashing seas, and the schooner's rigging that had drowned so many of the crew, including the pilot. Four bodies were found later - those of Mark Stenton from Brooklyn, cabin boy, of two seamen from Germany and Scandinavia, and that of a man from Nova Scotia or Maine. Furthermore, some bodies without heads, legs or arms were also found which could not be identified. They were all buried in a mass grave in St Agnes cemetery.

The broken up and scattered wreck, was relocated in 1969. The bow lies at 56 ft deep on position 49°53′38″N 06°22′55″W to the north-east of Shag Rock and the stern, with the spanker mast 400m to the south-west.[1] It can be visited by scuba divers under calm weather conditions. One of the anchors is now built into the outside wall of Bleak House, Broadstairs, the former home of Charles Dickens, and can be seen with a picture of the schooner.

Memorial

In 2008 a memorial seat was blessed by the Reverend Guy Scott in the churchyard of St Agnes, the nearest inhabitable island to the wreck and the home of the pilot, Billy "Cook" Hicks. The seat, made of granite from a St Breward quarry, faces the mass, unmarked grave of many of Thomas W. Lawson's dead

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_W._Lawson_(ship)