Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

12 - 15 November 1942 – World War II: Naval Battle of Guadalcanal between Japanese and American forces near Guadalcanal - Day 3/4 (14/15th)

Second Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, 14–15 November

Prelude

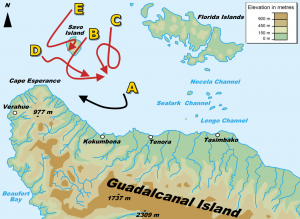

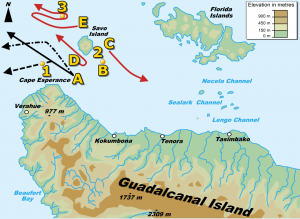

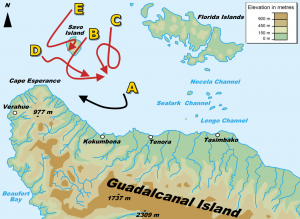

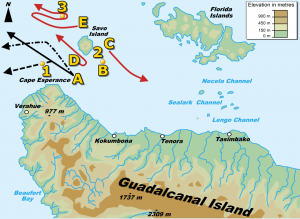

First phase of the engagement, 23:17–23:30, 14 November. Red lines are Japanese warship forces and black line is the U.S. warship force.

Kondo's force approached Guadalcanal via Indispensable Strait around midnight on 14 November, and a quarter moon provided moderate visibility of about 7 km (3.8 nmi; 4.3 mi). The force included

Kirishima, heavy cruisers

Atago and

Takao, light cruisers

Nagara and

Sendai, and nine destroyers, some of the destroyers being survivors (along with

Kirishima and

Nagara) of the first night engagement two days prior. Kondo flew his flag in the cruiser

Atago.

Low on undamaged ships, Admiral

William Halsey, Jr., detached the new battleships

Washington and

South Dakota, of

Enterprise's support group, together with four destroyers, as TF 64 under Admiral

Willis A. Lee to defend Guadalcanal and Henderson Field. It was a scratch force; the battleships had operated together for only a few days, and their four escorts were from four different divisions—chosen simply because, of the available destroyers, they had the most fuel.

[92] The U.S. force arrived in Ironbottom Sound in the evening of 14 November and began patrolling around Savo Island. The U.S. warships were in column formation with the four destroyers in the lead, followed by

Washington, with

South Dakota bringing up the rear. At 22:55 on 14 November, radar on

South Dakota and

Washington began picking up Kondo's approaching ships near Savo Island, at a distance of around 18,000 m (20,000 yd).

Action

Kondo split his force into several groups, with one group—commanded by

Shintaro Hashimoto and consisting of

Sendai and destroyers

Shikinami and

Uranami ("C" on the maps)—sweeping along the east side of Savo Island, and destroyer

Ayanami("B" on the maps) sweeping counterclockwise around the southwest side of Savo Island to check for the presence of Allied ships. The Japanese ships spotted Lee's force around 23:00, though Kondo misidentified the battleships as cruisers. Kondo ordered the

Sendai group of ships—plus

Nagara and four destroyers ("D" on the maps)—to engage and destroy the U.S. force before he brought the bombardment force of

Kirishima and heavy cruisers ("E" on the maps) into Ironbottom Sound.

[89] The U.S. ships ("A" on the maps) detected the

Sendai force on radar but did not detect the other groups of Japanese ships. Using radar targeting, the two U.S. battleships opened fire on the

Sendai group at 23:17. Admiral Lee ordered a cease fire about five minutes later after the northern group disappeared from his ship's radar. However,

Sendai,

Uranami, and

Shikinami were undamaged and circled out of the danger area.

Second phase of the engagement, 23:30–02:00. Red lines are Japanese warship forces and black lines are U.S. warships. Numbered yellow dots represent sinking warships.

Meanwhile, the four U.S. destroyers in the vanguard of the U.S. formation began engaging both

Ayanami and the

Nagara group of ships at 23:22.

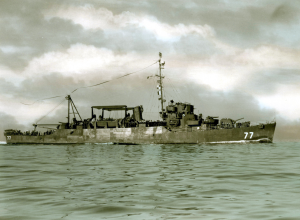

Nagara and her escorting destroyers responded effectively with accurate gunfire and torpedoes, and destroyers

Walke and

Preston were hit and sunk within 10 minutes with heavy loss of life. The destroyer

Benham had part of her bow blown off by a torpedo and had to retreat (she sank the next day), and destroyer

Gwin was hit in her engine room and put out of the fight. However, the U.S. destroyers had completed their mission as screens for the battleships, absorbing the initial impact of contact with the enemy, although at great cost. Lee ordered the retirement of

Benham and

Gwin at 23:48.

Washington passed through the area still occupied by the damaged and sinking U.S. destroyers and fired on

Ayanami with her secondary batteries, setting her afire. Following close behind,

South Dakota suddenly suffered a series of electrical failures, reportedly during repairs when her chief engineer locked down a

circuit breaker in violation of safety procedures, causing her circuits repeatedly to go into

series, making her radar, radios, and most of her gun batteries inoperable. However, she continued to follow

Washington towards the western side of Savo Island until 23:35, when

Washington changed course left to pass to the southward behind the burning destroyers.

South Dakota tried to follow but had to turn to starboard to avoid

Benham, which resulted in the ship being silhouetted by the fires of the burning destroyers and made her a closer and easier target for the Japanese.

Receiving reports of the destruction of the U.S. destroyers from

Ayanami and his other ships, Kondo pointed his bombardment force towards Guadalcanal, believing that the U.S. warship force had been defeated. His force and the two U.S. battleships were now heading towards each other.

Almost blind and unable to effectively fire her main and secondary armament,

South Dakota was illuminated by searchlights and targeted by gunfire and torpedoes by most of the ships of the Japanese force, including

Kirishima, beginning around midnight on 15 November. Although able to score a few hits on

Kirishima,

South Dakota took 26 hits—some of which did not explode—that completely knocked out her communications and remaining gunfire control operations, set portions of her upper decks on fire, and forced her to try to steer away from the engagement. All of the Japanese torpedoes missed. Admiral Lee later described the cumulative effect of the gunfire damage to

South Dakota as to, "render one of our new battleships deaf, dumb, blind, and impotent".

South Dakota's crew casualties were 39 killed and 59 wounded, and she turned away from the battle at 00:17 without informing Admiral Lee, though observed by Kondo's lookouts.

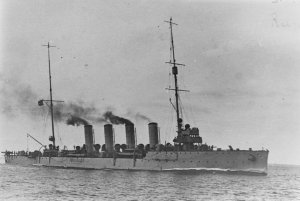

Washington

Washington fires upon

Kirishimaduring the battle on 15 November.

The Japanese ships continued to concentrate their fire on

South Dakota and none detected

Washington approaching to within 9,000 yd (8,200 m).

Washington was tracking a large target (

Kirishima) for some time but refrained from firing since there was a chance it could be

South Dakota.

Washington had not been able to track

South Dakota's movements because she was in a blind spot in

Washington's radar and Lee could not raise her on the radio to confirm her position. When the Japanese illuminated and fired on

South Dakota, all doubts were removed as to which ships were friend or foe. From this close range,

Washington opened fire and quickly hit

Kirishima with at least nine (and possibly up to 20) main battery shells and at least seventeen secondary ones, disabling all of

Kirishima's main gun turrets, causing major flooding, and setting her aflame.

Kirishima was hit below the waterline and suffered a jammed rudder, causing her to circle uncontrollably to port.

At 00:25, Kondo ordered all of his ships that were able to converge and destroy any remaining U.S. ships. However, the Japanese ships still did not know where

Washington was located, and the other surviving U.S. ships had already departed the battle area.

Washington steered a northwesterly course toward the

Russell Islands to draw the Japanese force away from Guadalcanal and the presumably damaged

South Dakota. The Imperial ships finally sighted

Washington and launched several torpedo attacks, but she avoided all of them and also avoided running aground in shallow waters. At length, believing that the way was clear for the transport convoy to proceed to Guadalcanal (but apparently disregarding the threat of air attack in the morning), Kondo ordered his remaining ships to break contact and retire from the area about 01:04, which most of the Japanese warships complied with by 01:30.

Aftermath

Ayanami was

scuttled by

Uranami at 2:00, while

Kirishima capsized and sank by 03:25 on 15 November.

Uranami rescued survivors from

Ayanami and destroyers

Asagumo,

Teruzuki, and

Samidare rescued the remaining crew from

Kirishima. In the engagement, 242 U.S. and 249 Japanese sailors died. The engagement was one of only two battleship-against-battleship surface battles in the entire Pacific campaign of World War II, the other being at the

Surigao Strait during the

Battle of Leyte Gulf.

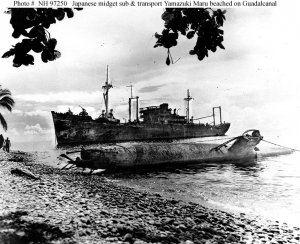

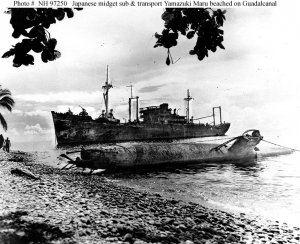

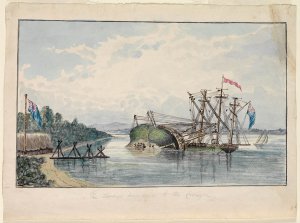

Two Japanese transports beached on Guadalcanal and burning on 15 November

The four Japanese transports beached themselves at Tassafaronga on Guadalcanal by 04:00 on 15 November, and Tanaka and the escort destroyers departed and raced back up the Slot toward safer waters. The transports were attacked, beginning at 05:55, by U.S. aircraft from Henderson Field and elsewhere, and by field artillery from U.S. ground forces on Guadalcanal. Later, destroyer

Meade approached and opened fire on the beached transports and surrounding area. These attacks set the transports afire and destroyed any equipment on them that the Japanese had not yet managed to unload. Only 2,000 to 3,000 of the embarked troops made it to Guadalcanal, and most of their ammunition and food were lost.

Yamamoto's reaction to Kondo's failure to accomplish his mission of neutralizing Henderson Field and ensuring the safe landing of troops and supplies was milder than his earlier reaction to Abe's withdrawal, perhaps because of Imperial Navy culture and politics. Kondo, who also held the position of second in command of the Combined Fleet, was a member of the upper staff and battleship "clique" of the Imperial Navy while Abe was a career destroyer specialist. Admiral Kondo was not reprimanded or reassigned but instead was left in command of one of the large ship fleets based at Truk.

Significance

The failure to deliver to Guadalcanal most of the troops and especially supplies in the convoy prevented the Japanese from launching another offensive to retake Henderson Field. Thereafter, the Imperial Navy was only able to deliver subsistence supplies and a few replacement troops to Japanese Army forces on Guadalcanal. Because of the continuing threat from Allied aircraft based at Henderson Field, plus nearby U.S.

aircraft carriers, the Japanese had to continue to rely on Tokyo Express warship deliveries to their forces on Guadalcanal. However, these supplies and replacements were not enough to sustain Japanese troops on the island, who – by 7 December 1942 – were losing about 50 men each day from malnutrition, disease, and Allied ground and air attacks. On 12 December, the Japanese Navy proposed that Guadalcanal be abandoned. Despite opposition from Japanese Army leaders, who still hoped that Guadalcanal could be retaken from the Allies, Japan's

Imperial General Headquarters—with approval from the

Emperor—agreed on 31 December to the

evacuation of all Japanese forces from the island and establishment of a new line of defense for the Solomons on

New Georgia.

The wreck of one of the four Japanese transports "Kinugawa Maru" beached and destroyed at Guadalcanal on 15 November 1942, photographed one year later.

The wreck of the "Yamazuki Maru" and a Japanese

midget submarine off Guadalcanal

Thus, the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal was the last major attempt by the Japanese to seize control of the seas around Guadalcanal or to retake the island. In contrast, the U.S. Navy was thereafter able to resupply the U.S. forces at Guadalcanal at will, including the delivery of two fresh divisions by late December 1942. The inability to neutralize Henderson Field doomed the Japanese effort to successfully combat the Allied conquest of Guadalcanal. The last Japanese resistance in the Guadalcanal campaign ended on 9 February 1943, with the successful evacuation of most of the surviving Japanese troops from the island by the Japanese Navy in

Operation Ke. Building on their success at Guadalcanal and elsewhere, the Allies continued their campaign against Japan, which culminated in Japan's defeat and the end of World War II. U.S. President

Franklin Roosevelt, upon learning of the results of the battle, commented, "It would seem that the turning point in this war has at last been reached."

Historian

Eric Hammel sums up the significance of the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal this way:

On November 12, 1942, the (Japanese) Imperial Navy had the better ships and the better tactics. After November 15, 1942, its leaders lost heart and it lacked the strategic depth to face the burgeoning U.S. Navy and its vastly improving weapons and tactics. The Japanese never got better while, after November 1942, the U.S. Navy never stopped getting better.

General

Alexander Vandegrift, the commander of the troops on Guadalcanal, paid tribute to the sailors who fought the battle:

We believe the enemy has undoubtedly suffered a crushing defeat. We thank Admiral Kinkaid for his intervention yesterday. We thank Lee for his sturdy effort last night. Our own aircraft has been grand in its relentless hammering of the foe. All those efforts are appreciated but our greatest homage goes to Callaghan, Scott and their men who with magnificent courage against seemingly hopeless odds drove back the first hostile attack and paved the way for the success to follow. To them the men of Cactus lift their battered helmets in deepest admiration.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Naval_Battle_of_Guadalcanal

ett, undertook the task and by about 5 o'clock in the morning Phipps was close enough to start an action with one of the luggers. For a quarter of an hour the lugger's crew fired small arms at Phipps and tried to run her ashore. Bell decided that as the water was only three and a half fathoms deep, the only way to capture the lugger was by boarding. Lieutenant Robert Tryon led the boarding party. The lugger surrendered after a few minutes fighting during which a seaman was killed and Tryon was dangerously wounded.[8] Tyson died eight weeks later in London of complications from his wounds, which were the result of his being hit by a cannonball accidentally discharged from Phipps.

ett, undertook the task and by about 5 o'clock in the morning Phipps was close enough to start an action with one of the luggers. For a quarter of an hour the lugger's crew fired small arms at Phipps and tried to run her ashore. Bell decided that as the water was only three and a half fathoms deep, the only way to capture the lugger was by boarding. Lieutenant Robert Tryon led the boarding party. The lugger surrendered after a few minutes fighting during which a seaman was killed and Tryon was dangerously wounded.[8] Tyson died eight weeks later in London of complications from his wounds, which were the result of his being hit by a cannonball accidentally discharged from Phipps.