Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

14 October 1905 – Launch of SS Kronprinzessin Cecilie was a Hamburg-America Line passenger ship

Kronprinzessin Cecilie was a Hamburg-America Line passenger ship launched on 14 October 1905 by Krupp Aktiengesellschaft Germaniawerft at Kiel, Germany. The ship was placed on the South American service and soon to be overshadowed by the Norddeutscher Lloyd four stack liner Kronprinzessin Cecilie launched on 1 December 1906 that, at 18,372 GRT, was over twice the 8,688 GRT tonnage of the Hamburg-America Line ship.

The ship, after leaving New York on 25 July 1914 sought refuge in the port of Falmouth, Cornwall, Britain not yet having declared war, from a French cruiser. The ship was given permission to leave on Britain's entry into the war, though British and French warships were waiting, refused, and as a result was condemned in a British court, requisitioned by the government and taken into the Royal Navy as HMS Princess in 1915.

The Hamburg-America Cruising Steamer Kronprinzessin Cecilie (1905)

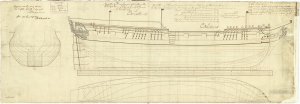

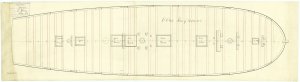

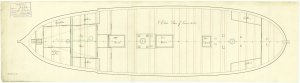

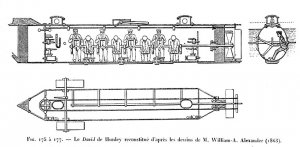

Construction and design

Kronprinzessin Cecilie was built for the Hamburg-America Line by Krupp Aktiengesellschaft Germaniawerft, Kiel, under a June 1904 contract in which the keel was laid on 1 January 1905 and the ship was launched on 14 October 1905.

The ship was 143.25 metres (470 ft 0 in) long between perpendiculars, by 16.76 metres (55 ft 0 in) extreme beam.

Two quadruple expansion main engines, with cylinders of 60 centimetres (23.6 in), 127.5 centimetres (50.2 in), 187.5 centimetres (73.8 in) and 87.5 centimetres (34.4 in) with a stroke of 135.7 centimetres (53.4 in), each developed about 3,035 indicated horsepower (2,263 kW) at 79 revolutions. The engines were in a central engine room without separation bulkheads with common starting and work platforms between and drove two manganese bronze four-bladed propellers, turning outboard going ahead, with 5.41 metres (17.7 ft) diameter and 6.2 metres (20.3 ft) pitch. Steam was provided by three double ended, with three furnaces at each end, and one single ended boiler with three furnaces at the front end for a total of twenty-one furnaces. Electrical power at 102 volts for lights and some auxiliary equipment, including radio, was generated by three dynamos, two aft in the engine room and one above the waterline forward of the main deck engine hatch, each delivering 400 amperes.

Commercial service

On 20 February 1906 the ship steamed from Kiel to Hamburg where she was delivered to Hamburg-America on 24 February and left on her maiden voyage on 14 March for Veracruz and Tampico, Mexico. On the crossing the ship's average speed was 14.41 knots (16.58 mph; 26.69 km/h).

The ship having the same name as the larger Norddeutscher Lloyd ship resulted in occasional confusion as with reports of Kronprinzessin Cecilie being involved in transporting arms to Mexico for General Huerta and taking the Mexican delegation to the mediation conference even while the Norddeutscher Lloyd ship was arriving in New York with the New York Times noting: "the fact that there are two steamers named Kronprinzessin Cecilie has caused much confusion in the minds" of its readers.

The ship was reported to have aboard arms for General Huerta but did not land them at Veracruz and proceeded to Puerto, Mexico. The Mexican delegation of Emilio Rabasa, Augustin Rodriguez and Luis Eiguero departed Veracruz on 10 May 1914 aboard Kronprinzessin Cecilie for the mediation conference to be held at Niagara Falls, Ontario to resolve the dispute between Huerta and the United States.

Kronprinzessin Cecilie had been engaged in tourist service and transport of the Mexican delegation had departed New York on 25 July 1914. Under pursuit by a French cruiser she had put into Falmouth before Britain had declared war.[8] In late March 1916 Kronprinzessin Cecilie and SS Prinz Adalbert were condemned in a British Prize Court on the basis that the ships had been granted permission to leave, even though French and British warships were waiting, and that refusal to leave had removed the ships from Hague Convention protection.[8] At the close of the court proceedings the British government announced the ships had been requisitioned.

HMS Princess

For other ships with the same name, see HMS Princess.

Kronprinzessin Cecilie was taken into the Royal Navy and renamed to become HMS Princess in 1915 and converted to a dummy for the battleship HMS Ajax, with superstructure and guns made of wood. The work was done in Belfast by Harland and Wolff. Princess/Ajax patrolled around Loch Ewe until October 1915, when she was decommissioned and converted to a proper armed merchant cruiser, with eight 6-inch (152 mm) guns. She recommissioned on 6 May 1916 and went to East Africa, where she served until October 1917, before being paid off in Bombay.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SS_Kronprinzessin_Cecilie_(1905)

14 October 1905 – Launch of SS Kronprinzessin Cecilie was a Hamburg-America Line passenger ship

Kronprinzessin Cecilie was a Hamburg-America Line passenger ship launched on 14 October 1905 by Krupp Aktiengesellschaft Germaniawerft at Kiel, Germany. The ship was placed on the South American service and soon to be overshadowed by the Norddeutscher Lloyd four stack liner Kronprinzessin Cecilie launched on 1 December 1906 that, at 18,372 GRT, was over twice the 8,688 GRT tonnage of the Hamburg-America Line ship.

The ship, after leaving New York on 25 July 1914 sought refuge in the port of Falmouth, Cornwall, Britain not yet having declared war, from a French cruiser. The ship was given permission to leave on Britain's entry into the war, though British and French warships were waiting, refused, and as a result was condemned in a British court, requisitioned by the government and taken into the Royal Navy as HMS Princess in 1915.

The Hamburg-America Cruising Steamer Kronprinzessin Cecilie (1905)

Construction and design

Kronprinzessin Cecilie was built for the Hamburg-America Line by Krupp Aktiengesellschaft Germaniawerft, Kiel, under a June 1904 contract in which the keel was laid on 1 January 1905 and the ship was launched on 14 October 1905.

The ship was 143.25 metres (470 ft 0 in) long between perpendiculars, by 16.76 metres (55 ft 0 in) extreme beam.

Two quadruple expansion main engines, with cylinders of 60 centimetres (23.6 in), 127.5 centimetres (50.2 in), 187.5 centimetres (73.8 in) and 87.5 centimetres (34.4 in) with a stroke of 135.7 centimetres (53.4 in), each developed about 3,035 indicated horsepower (2,263 kW) at 79 revolutions. The engines were in a central engine room without separation bulkheads with common starting and work platforms between and drove two manganese bronze four-bladed propellers, turning outboard going ahead, with 5.41 metres (17.7 ft) diameter and 6.2 metres (20.3 ft) pitch. Steam was provided by three double ended, with three furnaces at each end, and one single ended boiler with three furnaces at the front end for a total of twenty-one furnaces. Electrical power at 102 volts for lights and some auxiliary equipment, including radio, was generated by three dynamos, two aft in the engine room and one above the waterline forward of the main deck engine hatch, each delivering 400 amperes.

Commercial service

On 20 February 1906 the ship steamed from Kiel to Hamburg where she was delivered to Hamburg-America on 24 February and left on her maiden voyage on 14 March for Veracruz and Tampico, Mexico. On the crossing the ship's average speed was 14.41 knots (16.58 mph; 26.69 km/h).

The ship having the same name as the larger Norddeutscher Lloyd ship resulted in occasional confusion as with reports of Kronprinzessin Cecilie being involved in transporting arms to Mexico for General Huerta and taking the Mexican delegation to the mediation conference even while the Norddeutscher Lloyd ship was arriving in New York with the New York Times noting: "the fact that there are two steamers named Kronprinzessin Cecilie has caused much confusion in the minds" of its readers.

The ship was reported to have aboard arms for General Huerta but did not land them at Veracruz and proceeded to Puerto, Mexico. The Mexican delegation of Emilio Rabasa, Augustin Rodriguez and Luis Eiguero departed Veracruz on 10 May 1914 aboard Kronprinzessin Cecilie for the mediation conference to be held at Niagara Falls, Ontario to resolve the dispute between Huerta and the United States.

Kronprinzessin Cecilie had been engaged in tourist service and transport of the Mexican delegation had departed New York on 25 July 1914. Under pursuit by a French cruiser she had put into Falmouth before Britain had declared war.[8] In late March 1916 Kronprinzessin Cecilie and SS Prinz Adalbert were condemned in a British Prize Court on the basis that the ships had been granted permission to leave, even though French and British warships were waiting, and that refusal to leave had removed the ships from Hague Convention protection.[8] At the close of the court proceedings the British government announced the ships had been requisitioned.

HMS Princess

For other ships with the same name, see HMS Princess.

Kronprinzessin Cecilie was taken into the Royal Navy and renamed to become HMS Princess in 1915 and converted to a dummy for the battleship HMS Ajax, with superstructure and guns made of wood. The work was done in Belfast by Harland and Wolff. Princess/Ajax patrolled around Loch Ewe until October 1915, when she was decommissioned and converted to a proper armed merchant cruiser, with eight 6-inch (152 mm) guns. She recommissioned on 6 May 1916 and went to East Africa, where she served until October 1917, before being paid off in Bombay.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SS_Kronprinzessin_Cecilie_(1905)