Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

16 April 1767 - Birth of Richard Parker, later President of the "Floating Republic" at the Nore,

Richard Parker (16 April 1767 – 30 June 1797) was an English sailor executed for his role as president of the so-called "Floating Republic", a naval mutiny in the Royal Navy which took place at the Nore between 12 May and 16 June 1797.

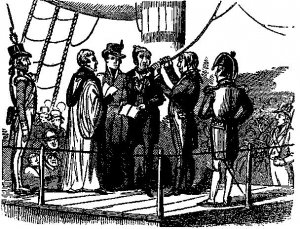

Richard Parker about to be hanged for mutiny

Early life and career

He was born in Exeter, the son of a successful baker, and was apprenticed as a navigator in 1779. From 1782 until 1793 he served on various ships of the Royal Navy mainly in the Mediterranean and India service, achieving the rank of master's mate and a probationary period as lieutenant. In December 1793 he was serving as a midshipman aboard HMS Assurance when he refused an order to clear away his hammock at daybreak. The clearing of hammocks was a common obligation of ordinary seamen but was less routinely demanded of petty officers. Parker's refusal to follow the order led to a court martial for insubordination and a reduction to the rank of seaman. He was eventually discharged from the Navy in November 1794.

Parker returned to Exeter to reunite with his wife Anne. He struggled to earn a living and was jailed for outstanding debts in early 1797. After three weeks in jail, he accepted a quota of £20 in return for reenlistment in the navy, his despair at the prospect such that he attempted suicide on the way to the embarkation point at Sheerness by flinging himself overboard.

The Nore mutiny

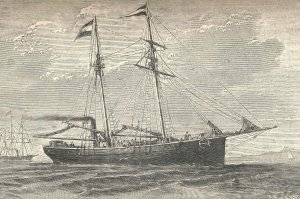

Upon his arrival at the Nore, one of the bases of the North Sea fleet, Parker was assigned to the ship HMS Sandwich which was widely regarded[by whom?] as one of the worst in terms of its squalid and overcrowded conditions. It was on the Sandwich, on 12 May, that the Nore mutiny broke out; Parker played no role in organizing the mutiny, but he was soon invited by the mutineers to join their ranks, and was subsequently appointed "President of the Delegates of the Fleet" due to his obvious intelligence, education, and empathy with the suffering of the sailors.

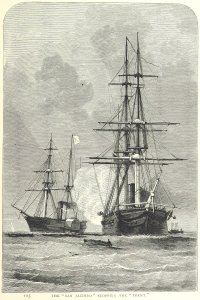

His degree of control over the direction of the mutiny was limited; his role as President was largely symbolic, mainly involving supervision of the processions of delegates in boats that plied between the involved ships for communication and morale purposes. Despite the chaotic nature of the mutiny and his ill-defined powers, Parker did manage to exert control, as on 2 June when the sloop HMS Hound arrived at the Nore and was boarded by a party of delegates. The Hound's crew and commander violently resisted this intrusion, but Parker’s arrival and display of authority quickly convinced the Captain to submit and join the mutiny. During the mutineers' blockade of the Thames, only ships bearing a pass signed by Parker were allowed to pass without being stopped and searched.

Crisis and collapse

On 6 June he organized a meeting of the delegates with Lord Northesk to whom he handed a petition and a form of ultimatum that their grievances be addressed within a period of 54 hours, after which he warned "such steps by the Fleet will be taken as will astonish their dear countrymen". The increasing tension led to the desertion of the mutiny by several ships and even some of the radical delegates began to sense the end and fled abroad. The fear that the by now thoroughly demonized Parker would also escape led to a reward of £500 (equivalent to £50,000 in present-day terms) being posted for his arrest.

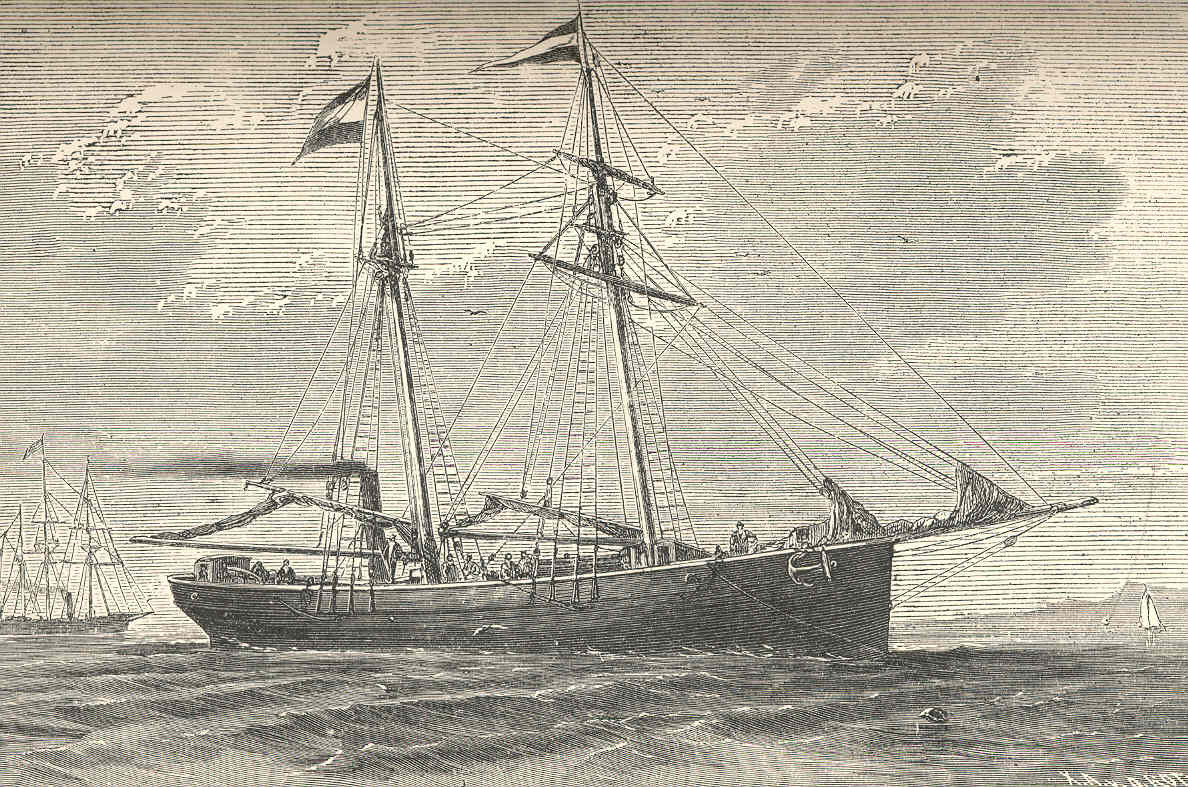

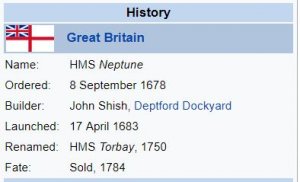

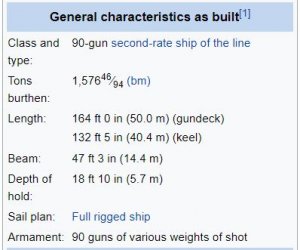

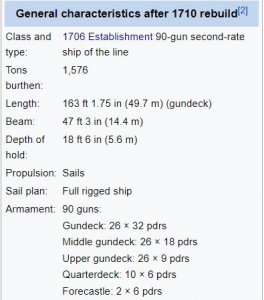

When the delegates' deadline passed without reply, Parker ordered that the fleet sail for Texel on the morning of 9 June. However, no ship moved when the signal to sail was given and the mutiny was effectively over. Parker was arrested on 13 June, brought briefly to Sheerness under heavy guard, then taken to HMS Neptune the flag ship of Commodore Sir Erasmus Gower where he was court-martialled, found guilty of treason and piracy and sentenced to death. He was executed on board the Sandwich amid much ceremony on 30 June 1797.

His body was not publicly gibbetted after death, contrary to the wishes of King George III.[citation needed] Parker's wife Anne, who had worked tirelessly to prevent his execution, later rescued his body from an unconsecrated burial ground and smuggled it into London, where crowds gathered to see it. After receiving Christian rites, it was buried in the grounds of St Mary Matfelon Church, Whitechapel.. His death mask was thought to be at Sir John Soane's Museum in London, but it is actually the death mask of Oliver Cromwell.

A song entitled "The Death of Parker" was collected at St Merryn, Cornwall, in 1905.

Popular culture

Parker's story was the subject of the folk-punk song "The Colours" by The Men They Couldn't Hang. The song is sung from Parker's point of view, exploring his last thoughts as he is led to the scaffold.

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

16 April 1767 - Birth of Richard Parker, later President of the "Floating Republic" at the Nore,

Richard Parker (16 April 1767 – 30 June 1797) was an English sailor executed for his role as president of the so-called "Floating Republic", a naval mutiny in the Royal Navy which took place at the Nore between 12 May and 16 June 1797.

Richard Parker about to be hanged for mutiny

Early life and career

He was born in Exeter, the son of a successful baker, and was apprenticed as a navigator in 1779. From 1782 until 1793 he served on various ships of the Royal Navy mainly in the Mediterranean and India service, achieving the rank of master's mate and a probationary period as lieutenant. In December 1793 he was serving as a midshipman aboard HMS Assurance when he refused an order to clear away his hammock at daybreak. The clearing of hammocks was a common obligation of ordinary seamen but was less routinely demanded of petty officers. Parker's refusal to follow the order led to a court martial for insubordination and a reduction to the rank of seaman. He was eventually discharged from the Navy in November 1794.

Parker returned to Exeter to reunite with his wife Anne. He struggled to earn a living and was jailed for outstanding debts in early 1797. After three weeks in jail, he accepted a quota of £20 in return for reenlistment in the navy, his despair at the prospect such that he attempted suicide on the way to the embarkation point at Sheerness by flinging himself overboard.

The Nore mutiny

Upon his arrival at the Nore, one of the bases of the North Sea fleet, Parker was assigned to the ship HMS Sandwich which was widely regarded[by whom?] as one of the worst in terms of its squalid and overcrowded conditions. It was on the Sandwich, on 12 May, that the Nore mutiny broke out; Parker played no role in organizing the mutiny, but he was soon invited by the mutineers to join their ranks, and was subsequently appointed "President of the Delegates of the Fleet" due to his obvious intelligence, education, and empathy with the suffering of the sailors.

His degree of control over the direction of the mutiny was limited; his role as President was largely symbolic, mainly involving supervision of the processions of delegates in boats that plied between the involved ships for communication and morale purposes. Despite the chaotic nature of the mutiny and his ill-defined powers, Parker did manage to exert control, as on 2 June when the sloop HMS Hound arrived at the Nore and was boarded by a party of delegates. The Hound's crew and commander violently resisted this intrusion, but Parker’s arrival and display of authority quickly convinced the Captain to submit and join the mutiny. During the mutineers' blockade of the Thames, only ships bearing a pass signed by Parker were allowed to pass without being stopped and searched.

Crisis and collapse

On 6 June he organized a meeting of the delegates with Lord Northesk to whom he handed a petition and a form of ultimatum that their grievances be addressed within a period of 54 hours, after which he warned "such steps by the Fleet will be taken as will astonish their dear countrymen". The increasing tension led to the desertion of the mutiny by several ships and even some of the radical delegates began to sense the end and fled abroad. The fear that the by now thoroughly demonized Parker would also escape led to a reward of £500 (equivalent to £50,000 in present-day terms) being posted for his arrest.

When the delegates' deadline passed without reply, Parker ordered that the fleet sail for Texel on the morning of 9 June. However, no ship moved when the signal to sail was given and the mutiny was effectively over. Parker was arrested on 13 June, brought briefly to Sheerness under heavy guard, then taken to HMS Neptune the flag ship of Commodore Sir Erasmus Gower where he was court-martialled, found guilty of treason and piracy and sentenced to death. He was executed on board the Sandwich amid much ceremony on 30 June 1797.

His body was not publicly gibbetted after death, contrary to the wishes of King George III.[citation needed] Parker's wife Anne, who had worked tirelessly to prevent his execution, later rescued his body from an unconsecrated burial ground and smuggled it into London, where crowds gathered to see it. After receiving Christian rites, it was buried in the grounds of St Mary Matfelon Church, Whitechapel.. His death mask was thought to be at Sir John Soane's Museum in London, but it is actually the death mask of Oliver Cromwell.

A song entitled "The Death of Parker" was collected at St Merryn, Cornwall, in 1905.

Popular culture

Parker's story was the subject of the folk-punk song "The Colours" by The Men They Couldn't Hang. The song is sung from Parker's point of view, exploring his last thoughts as he is led to the scaffold.

s

s