Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

16 September 1782 - The Central Atlantic hurricane of 1782, was a hurricane that hit the fleet of British Admiral Thomas Graves as it sailed across the North Atlantic in September 1782. It is believed to have killed some 3,500 people.

The Central Atlantic hurricane of 1782, was a hurricane that hit the fleet of British Admiral Thomas Graves as it sailed across the North Atlantic in September 1782. It is believed to have killed some 3,500 people.

On 25 July Admiral Graves sailed a fleet from Bluefields, Jamaica, escorted by a naval force consisting of his flagship, the 74-gun HMS Ramillies, and the 74-gun ships HMS Canada and HMS Centaur, with the 36-gun frigate HMS Pallas. Graves was escorting a number of French ships captured by the British during operations off North and Central America. These were the 110-gun Ville de Paris, the 74-gun ships Glorieux and Hector and the 64-gun Ardent, all captured at the Battle of the Saintes by Sir George Brydges Rodney's fleet, and the 74-gun Caton, captured at the Battle of the Mona Passageby Sir Samuel Hood. Also with the fleet were a number of British merchant ships. Graves also had under his command the captured former-French 74-gun Jason, but she did not leave with the rest of the fleet, having stayed at Jamaica to complete her watering.

Sinking of the Ville de Paris

In the night of 5 September, Hector met the French frigates Aigle and Gloire; in the ensuing Action of 5 September 1782, Hector sustained severe damage, but was saved from capture by the rest of the convoy.

On 17 September 1782, the fleet under Admiral Graves was caught in a violent storm off the banks of Newfoundland. Ardent and Caton were forced to leave the fleet and make for a safe anchorage, Ardent returning to Jamaica and Caton making for Halifax in company with Pallas. Of the rest of the warships, only Canada and Jason survived to reach England. The French prizes Ville de Paris, Glorieux and Hector foundered, as did HMS Centaur. HMS Ramillies had to be abandoned, and was burnt. A number of the merchant fleet, including Dutton, British Queen, Withywood, Rodney, Ann, Minerva and Mentor also foundered. Altogether around 3,500 lives were lost from the various ships.

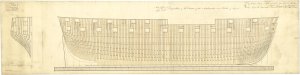

The French ship Glorieux was a second-rate 74-gun ship of the line in the French Navy. Built by Clairin Deslauriers at Rochefort and launched on 10 August 1756, she was rebuilt in 1777.

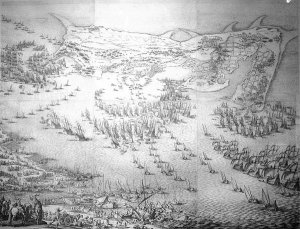

The view from Lady Juliana on the morning after the hurricane, featuring Glorieux along with HMS Centaurand HMS Ville de Paris

French service

On 30 August 1781, she was with the French fleet under Admiral de Grasse. According to French sources, the British sloop Loyalist and the frigate Guadeloupe were on picket duty in the Chesapeake when they encountered the French fleet. Guadeloupe escaped up the York River to York Town, where she would later be scuttled.[1] The English court martial records report that Loyalist was returning to the British fleet off the Jersey coast when she encountered the main French fleet. The French frigate Aigrette, with the 74-gun Glorieux in sight, was able to overtake Loyalist.[2] The French took her into service as Loyaliste in September, but then gave her to the Americans in November 1781.

The British captured Glorieux at the Battle of the Saintes on 12 April 1782 despite the best efforts of Denis Decrès, and commissioned her into the Royal Navy as HMS Glorieux or HMS Glorious the following day. She was rated as a third rate.

Fate

She sailed with the fleet for England on 25 July 1782 but was lost later that year in a hurricane storm off Newfoundland on 16–17 September, along with the other captured French prize ships Ville de Paris, Hector and Caton. Glorieux was lost with all hands, including her captain, Thomas Cadogan, son of Charles Cadogan, 3rd Baron Cadogan.

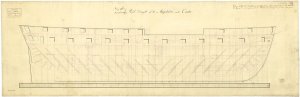

HMS Ramillies was a 74-gun third rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, launched on 15 April 1763 at Chatham Dockyard.

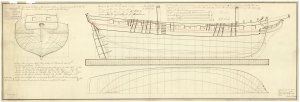

Loss of HMS Ramillies, September 1782: before the storm breaks

In 1782 she was the flagship of a fleet under Admiral Thomas Graves off Newfoundland. Ramillies was badly damaged in a violent storm of 1782, and was finally abandoned and burned on 21 September 1782.

On 16–19 September, she was escorting a convoy from Jamaica when they were hit by the storm. Frantic efforts were made to save her. All anchors, cannon, and masts were shipped over the side. The hull was bound together with rope, officers and men manned the pumps for 24 hours a day for 3 days. However despite all the water continued to rise. The exhausted crew were rescued by nearby merchantmen, and the last man, Captain Sylverius Moriarty, set her on fire as he left.

’The Storm increas'd. Distressed situation of the Ramillies when Day broke with the Dutton Store Ship foundering'

Robert Dodd painted a series of four documenting the tragedy. "The demise of the Ramillies" comprises: A storm coming on (shown right), ’The Storm increas'd (shown left), The Ramillies Water Logg'd with her Admiral & Crew quitting the Wreck, and The Ramillies Destroyed. In 1795 a set of four coloured mezzotints were engraved and published by Jukes from his shop at No.10 Howland Street.

Ville de Paris was a large three-decker French ship of the line that became famous as the flagship of the Comte de Grasse during the American Revolutionary War.

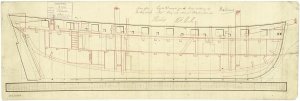

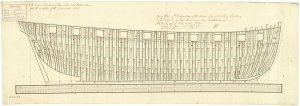

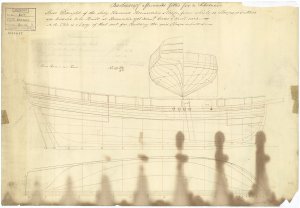

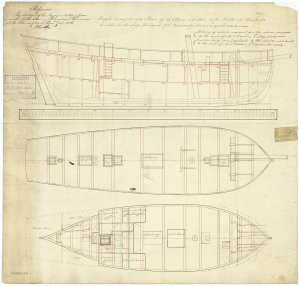

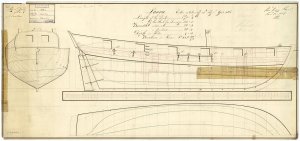

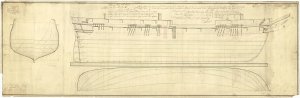

French warship Ville de Paris in 1764.

Originally laid down in 1757 as the 90-gun Impétueux, she was funded by the City of Paris and renamed Ville de Paris in 1762 as a result of the don des vaisseaux, Duc de Choiseul’s campaign to raise funds for the navy from the cities and provinces of France.

She was completed in 1764 as a 90-gun first rate, just too late to serve in the Seven Years' War. She was one of the first three-deckers to be completed for the French navy since the 1720s. In 1778, on the French entry into the American Revolutionary War she was commissioned at Brest, joining the fleet as the flagship of the Comte de Guichen. In July she fought in the indecisive Battle of Ushant (1778).

At some point during the next two years, she had an additional 14 small guns mounted on her previously unarmed quarterdeck, making her a 104-gun ship.

In March 1781 she sailed for the West Indies as flagship of a fleet of 20 ships of the line under the Comte de Grasse. She then fought at the Battle of Fort Royal, and the Battle of the Chesapeake. In 1782, she fought in the Battle of St. Kitts as De Grasse's flagship.

The Battle of the Saintes, 12 April 1782: surrender of the Ville de Paris by Thomas Whitcombe, painted 1783, shows Hood's Barfleur, centre, attacking the French flagship Ville de Paris, right.

At the Battle of the Saintes on 12 April 1782, the British fleet under Admiral Sir George Rodney defeated the French fleet under the Comte de Grasse, and captured Ville de Paris.

The ship did not live up to the motto of her namesake city, Fluctuat nec mergitur (Latin: Tossed by the waves, she does not sink), for she sank in September 1782 with other ships when the 1782 Central Atlantic hurricane hit the fleet off Newfoundland Admiral Graves was leading back to England. Ville de Paris sank with the loss of all hands but one.

The Hector was a 74-gun ship of the line of the French Navy, lead ship of her class.

Hector was launched on 23 July 1755, and commissioned under Captain Vilarzel d'Hélie.

In 1757, the departed Toulon on 18 March, arriving in Louisbourg on 15 June. Returning to Brest on 23 November with 5000 sick aboard, she spread the typhus to the town;[2] the ensuing epidemic caused 10 000 fatalities. She was then decommissioned and stayed in the reserve in Brest.

In July 1762, while cruising off Cap Français, she struck the bottom on a rock. The same spot had been the theatre of the wreck of French ship Dragon (1748) on 17 March of the same year. Between 1763 and 1777, she was decommissioned in Toulon. During the American War of Independence, she reactivated, sailing to the Delaware in July 1778. She arrived at Newport on 8 August 1778

On 14 August 1778, Hector and the 64-gun Vaillant captured the bombship HMS Thunder. The same day, she also captured the 16-gun HMS Senegal at Sandy Hook. Hector then took part in the Battle of Grenada on 6 July 1779 and in the Siege of Savannah, before returning to Brest, arriving on 10 December 1779. She was decommissioned in Lorient on 21 December, before rearming and thaking part in the Battle of the Chesapeake on 5 September 1781.

During the Battle of the Saintes, from 9 to 12 April 1782, she battled HMS Canada and Alcide and was captured. He captain, Lavicomté, died in the action.

The British took her to Jamaica, where she was repaired and recommissioned in the Royal Navy as HMS Hector.

She took part in the Action of 5 September 1782, where she was damaged by the frigates Aigle and Gloire.

Much damaged in this action and after suffering the 1782 Central Atlantic hurricane of 17 September, she sank on 4 October 1782. The privateer Hawke saved 200 of her crew.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Glorieux

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Ramillies_(1763)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_ship_Ville_de_Paris_(1764)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_ship_Hector_(1756)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1782_Central_Atlantic_hurricane

16 September 1782 - The Central Atlantic hurricane of 1782, was a hurricane that hit the fleet of British Admiral Thomas Graves as it sailed across the North Atlantic in September 1782. It is believed to have killed some 3,500 people.

The Central Atlantic hurricane of 1782, was a hurricane that hit the fleet of British Admiral Thomas Graves as it sailed across the North Atlantic in September 1782. It is believed to have killed some 3,500 people.

On 25 July Admiral Graves sailed a fleet from Bluefields, Jamaica, escorted by a naval force consisting of his flagship, the 74-gun HMS Ramillies, and the 74-gun ships HMS Canada and HMS Centaur, with the 36-gun frigate HMS Pallas. Graves was escorting a number of French ships captured by the British during operations off North and Central America. These were the 110-gun Ville de Paris, the 74-gun ships Glorieux and Hector and the 64-gun Ardent, all captured at the Battle of the Saintes by Sir George Brydges Rodney's fleet, and the 74-gun Caton, captured at the Battle of the Mona Passageby Sir Samuel Hood. Also with the fleet were a number of British merchant ships. Graves also had under his command the captured former-French 74-gun Jason, but she did not leave with the rest of the fleet, having stayed at Jamaica to complete her watering.

Sinking of the Ville de Paris

In the night of 5 September, Hector met the French frigates Aigle and Gloire; in the ensuing Action of 5 September 1782, Hector sustained severe damage, but was saved from capture by the rest of the convoy.

On 17 September 1782, the fleet under Admiral Graves was caught in a violent storm off the banks of Newfoundland. Ardent and Caton were forced to leave the fleet and make for a safe anchorage, Ardent returning to Jamaica and Caton making for Halifax in company with Pallas. Of the rest of the warships, only Canada and Jason survived to reach England. The French prizes Ville de Paris, Glorieux and Hector foundered, as did HMS Centaur. HMS Ramillies had to be abandoned, and was burnt. A number of the merchant fleet, including Dutton, British Queen, Withywood, Rodney, Ann, Minerva and Mentor also foundered. Altogether around 3,500 lives were lost from the various ships.

The French ship Glorieux was a second-rate 74-gun ship of the line in the French Navy. Built by Clairin Deslauriers at Rochefort and launched on 10 August 1756, she was rebuilt in 1777.

The view from Lady Juliana on the morning after the hurricane, featuring Glorieux along with HMS Centaurand HMS Ville de Paris

French service

On 30 August 1781, she was with the French fleet under Admiral de Grasse. According to French sources, the British sloop Loyalist and the frigate Guadeloupe were on picket duty in the Chesapeake when they encountered the French fleet. Guadeloupe escaped up the York River to York Town, where she would later be scuttled.[1] The English court martial records report that Loyalist was returning to the British fleet off the Jersey coast when she encountered the main French fleet. The French frigate Aigrette, with the 74-gun Glorieux in sight, was able to overtake Loyalist.[2] The French took her into service as Loyaliste in September, but then gave her to the Americans in November 1781.

The British captured Glorieux at the Battle of the Saintes on 12 April 1782 despite the best efforts of Denis Decrès, and commissioned her into the Royal Navy as HMS Glorieux or HMS Glorious the following day. She was rated as a third rate.

Fate

She sailed with the fleet for England on 25 July 1782 but was lost later that year in a hurricane storm off Newfoundland on 16–17 September, along with the other captured French prize ships Ville de Paris, Hector and Caton. Glorieux was lost with all hands, including her captain, Thomas Cadogan, son of Charles Cadogan, 3rd Baron Cadogan.

HMS Ramillies was a 74-gun third rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, launched on 15 April 1763 at Chatham Dockyard.

Loss of HMS Ramillies, September 1782: before the storm breaks

In 1782 she was the flagship of a fleet under Admiral Thomas Graves off Newfoundland. Ramillies was badly damaged in a violent storm of 1782, and was finally abandoned and burned on 21 September 1782.

On 16–19 September, she was escorting a convoy from Jamaica when they were hit by the storm. Frantic efforts were made to save her. All anchors, cannon, and masts were shipped over the side. The hull was bound together with rope, officers and men manned the pumps for 24 hours a day for 3 days. However despite all the water continued to rise. The exhausted crew were rescued by nearby merchantmen, and the last man, Captain Sylverius Moriarty, set her on fire as he left.

’The Storm increas'd. Distressed situation of the Ramillies when Day broke with the Dutton Store Ship foundering'

Robert Dodd painted a series of four documenting the tragedy. "The demise of the Ramillies" comprises: A storm coming on (shown right), ’The Storm increas'd (shown left), The Ramillies Water Logg'd with her Admiral & Crew quitting the Wreck, and The Ramillies Destroyed. In 1795 a set of four coloured mezzotints were engraved and published by Jukes from his shop at No.10 Howland Street.

Ville de Paris was a large three-decker French ship of the line that became famous as the flagship of the Comte de Grasse during the American Revolutionary War.

French warship Ville de Paris in 1764.

Originally laid down in 1757 as the 90-gun Impétueux, she was funded by the City of Paris and renamed Ville de Paris in 1762 as a result of the don des vaisseaux, Duc de Choiseul’s campaign to raise funds for the navy from the cities and provinces of France.

She was completed in 1764 as a 90-gun first rate, just too late to serve in the Seven Years' War. She was one of the first three-deckers to be completed for the French navy since the 1720s. In 1778, on the French entry into the American Revolutionary War she was commissioned at Brest, joining the fleet as the flagship of the Comte de Guichen. In July she fought in the indecisive Battle of Ushant (1778).

At some point during the next two years, she had an additional 14 small guns mounted on her previously unarmed quarterdeck, making her a 104-gun ship.

In March 1781 she sailed for the West Indies as flagship of a fleet of 20 ships of the line under the Comte de Grasse. She then fought at the Battle of Fort Royal, and the Battle of the Chesapeake. In 1782, she fought in the Battle of St. Kitts as De Grasse's flagship.

The Battle of the Saintes, 12 April 1782: surrender of the Ville de Paris by Thomas Whitcombe, painted 1783, shows Hood's Barfleur, centre, attacking the French flagship Ville de Paris, right.

At the Battle of the Saintes on 12 April 1782, the British fleet under Admiral Sir George Rodney defeated the French fleet under the Comte de Grasse, and captured Ville de Paris.

The ship did not live up to the motto of her namesake city, Fluctuat nec mergitur (Latin: Tossed by the waves, she does not sink), for she sank in September 1782 with other ships when the 1782 Central Atlantic hurricane hit the fleet off Newfoundland Admiral Graves was leading back to England. Ville de Paris sank with the loss of all hands but one.

The Hector was a 74-gun ship of the line of the French Navy, lead ship of her class.

Hector was launched on 23 July 1755, and commissioned under Captain Vilarzel d'Hélie.

In 1757, the departed Toulon on 18 March, arriving in Louisbourg on 15 June. Returning to Brest on 23 November with 5000 sick aboard, she spread the typhus to the town;[2] the ensuing epidemic caused 10 000 fatalities. She was then decommissioned and stayed in the reserve in Brest.

In July 1762, while cruising off Cap Français, she struck the bottom on a rock. The same spot had been the theatre of the wreck of French ship Dragon (1748) on 17 March of the same year. Between 1763 and 1777, she was decommissioned in Toulon. During the American War of Independence, she reactivated, sailing to the Delaware in July 1778. She arrived at Newport on 8 August 1778

On 14 August 1778, Hector and the 64-gun Vaillant captured the bombship HMS Thunder. The same day, she also captured the 16-gun HMS Senegal at Sandy Hook. Hector then took part in the Battle of Grenada on 6 July 1779 and in the Siege of Savannah, before returning to Brest, arriving on 10 December 1779. She was decommissioned in Lorient on 21 December, before rearming and thaking part in the Battle of the Chesapeake on 5 September 1781.

During the Battle of the Saintes, from 9 to 12 April 1782, she battled HMS Canada and Alcide and was captured. He captain, Lavicomté, died in the action.

The British took her to Jamaica, where she was repaired and recommissioned in the Royal Navy as HMS Hector.

She took part in the Action of 5 September 1782, where she was damaged by the frigates Aigle and Gloire.

Much damaged in this action and after suffering the 1782 Central Atlantic hurricane of 17 September, she sank on 4 October 1782. The privateer Hawke saved 200 of her crew.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Glorieux

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Ramillies_(1763)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_ship_Ville_de_Paris_(1764)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_ship_Hector_(1756)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1782_Central_Atlantic_hurricane