Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

Other Events on 17 September

1574 – Death of Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, Spanish admiral and explorer, founded St. Augustine, Florida (b. 1519)

Pedro Menéndez de Avilés (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈpeðɾo mẽˈnẽndeθ ðe aβiˈles]; 15 February 1519 – 17 September 1574) was a Spanish admiral and explorer from the region of Asturias, Spain, who is remembered for planning the first regular trans-oceanic convoys and for founding St. Augustine, Florida, in 1565. This was the first successful Spanish settlement in La Florida and the most significant city in the region for nearly three centuries. St. Augustine is the oldest continuously-inhabited, European-established settlement in the continental United States. Menéndez de Avilés was also the first governor of Florida (1565–74).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pedro_Menéndez_de_Avilés

1812 Boats of HMS Eagle (1804 – 74 – Repulse-class), Cptn. Charles Rowley, capture 2 gunboats and 15 vessels laden with oil and destroy 6 gunboats off the mouths of the Po.

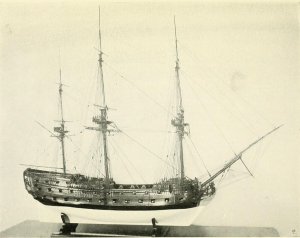

HMS Eagle was a 74-gun third rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, launched on 27 February 1804 at Northfleet.

On 11 November 1804, Glatton, together with Eagle, Majestic, Princess of Orange, Raisonable, Africiane, Inspector, Beaver, and the hired armed vessels Swift and Agnes, shared in the capture of the Upstalsboom, H.L. De Haase, Master.

In 1830 she was reduced to a 50-gun ship, and became a training ship in 1860. She was renamed HMS Eaglet in 1919, when she was the Royal Naval Reserve training centre for North West England. A fire destroyed Eagle in 1926

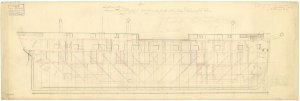

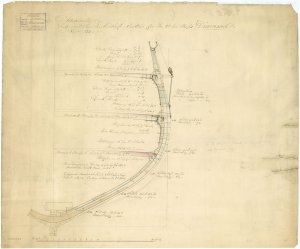

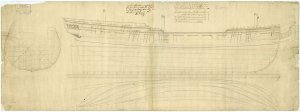

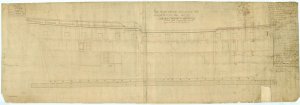

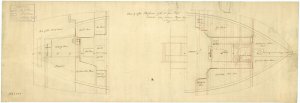

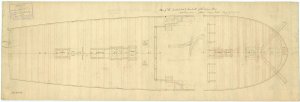

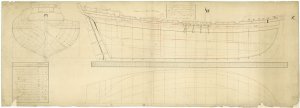

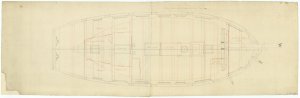

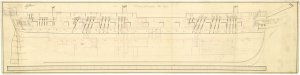

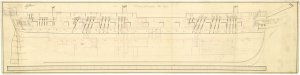

Scale: 1:48. Plan showing the inboard profile for 'Eagle' (1804), a 74-gun Third Rate, two-decker, as cut down to a 50-gun Fourth Rate Frigate at Chatham Dockyard in 1831. Signed by William Stone [Master Shipwright, Chatham Dockyard, 1830-1839].

Read more at http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/81585.html#514HmyLO46aZgtcm.99

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Eagle_(1804)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Repulse-class_ship_of_the_line

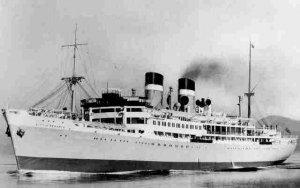

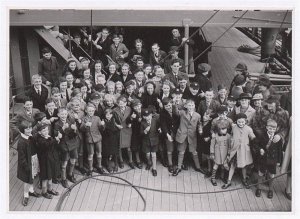

1921 – Launch of SS Munargo, commercial cargo and passenger ship

SS Munargo was a commercial cargo and passenger ship built for the Munson Steamship Lines by New York Shipbuilding Corp., Camden, New Jersey launched 17 September 1921. Munargo operated for the line in the New York-Bahamas-Cuba-Miami service passenger cargo trade. In June 1930 the United States and Mexican soccer teams took passage aboard Munargo from New York to Uruguay for the 1930 FIFA World Cup. The ship was acquired by the War Shipping Administration and immediately purchased by the War Department for service as a troop carrier during World War II. Shortly after acquisition the War Department transferred the ship to the U.S. Navy which commissioned the ship USS Munargo (AP-20). She operated in the Atlantic Ocean for the Navy until returned to the War Department in 1943 for conversion into the Hospital ship USAHS Thistle.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SS_Munargo_(1921)

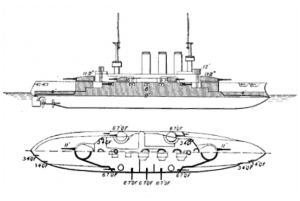

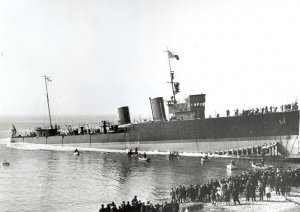

1940 – Italian destroyer Borea sunk

Italian destroyer Borea was a Turbine-class destroyer built for the Royal Italian Navy (Regia Marina) during late 1920s. She was named after a northerly wind, Borea, bringing frigid, dry air to the Italian peninsula.

In the evening of September 16, 1940 Borea together with destroyers Aquilone and Turbine was berthed in Benghazi harbor. At 19:30 steamers Maria Eugenia and Gloria Stella escorted by Fratelli Cairoli arrived from Tripoli bringing the total number of vessels present in the harbor to 32.[10] During the night of September 16 and 17, nine Swordfish bombers of 815 Squadron RAF carrying bombs and torpedoes, and six from 819 Squadron RAF armed with mines took off from Illustrious and approximately at 00:30 arrived undetected over Benghazi harbor. The anti-aircraft defenses opened fire but were unable to stop the attack. After passing over the harbor to determine their targets, Swordfish bombers made their first attack at 00:57 hitting and sinking Gloria Stella and severely damaging torpedo boat Cigno, harbor tug Salvatore Primo and an auxiliary vessel Giuliana. The bombers then conducted a second assault at 1:00 striking and sinking Maria Eugenia. Borea was also targeted during the second sweep, with the first bomb exploding between the destroyer and the steamer Città di Livorno but causing no damage to either ship. A short while later, a second bomb hit Borea on her port side, around 40/39 mm cannon platform. The bomb penetrated all the way down into the hold and exploded breaking the ship in two causing rapid flooding and sinking in shallow waters of the harbor. Due to rapid sinking most of the crew was able to easily abandon ship either by jumping or simply walking off the bridge and swimming towards destroyer Aquilone. There was a single casualty, a sailor who at the moment of the attack was sleeping in the engine room, near the area of bomb explosion.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Italian_destroyer_Borea_(1927)

Other Events on 17 September

1574 – Death of Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, Spanish admiral and explorer, founded St. Augustine, Florida (b. 1519)

Pedro Menéndez de Avilés (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈpeðɾo mẽˈnẽndeθ ðe aβiˈles]; 15 February 1519 – 17 September 1574) was a Spanish admiral and explorer from the region of Asturias, Spain, who is remembered for planning the first regular trans-oceanic convoys and for founding St. Augustine, Florida, in 1565. This was the first successful Spanish settlement in La Florida and the most significant city in the region for nearly three centuries. St. Augustine is the oldest continuously-inhabited, European-established settlement in the continental United States. Menéndez de Avilés was also the first governor of Florida (1565–74).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pedro_Menéndez_de_Avilés

1812 Boats of HMS Eagle (1804 – 74 – Repulse-class), Cptn. Charles Rowley, capture 2 gunboats and 15 vessels laden with oil and destroy 6 gunboats off the mouths of the Po.

HMS Eagle was a 74-gun third rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, launched on 27 February 1804 at Northfleet.

On 11 November 1804, Glatton, together with Eagle, Majestic, Princess of Orange, Raisonable, Africiane, Inspector, Beaver, and the hired armed vessels Swift and Agnes, shared in the capture of the Upstalsboom, H.L. De Haase, Master.

In 1830 she was reduced to a 50-gun ship, and became a training ship in 1860. She was renamed HMS Eaglet in 1919, when she was the Royal Naval Reserve training centre for North West England. A fire destroyed Eagle in 1926

Scale: 1:48. Plan showing the inboard profile for 'Eagle' (1804), a 74-gun Third Rate, two-decker, as cut down to a 50-gun Fourth Rate Frigate at Chatham Dockyard in 1831. Signed by William Stone [Master Shipwright, Chatham Dockyard, 1830-1839].

Read more at http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/81585.html#514HmyLO46aZgtcm.99

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Eagle_(1804)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Repulse-class_ship_of_the_line

1921 – Launch of SS Munargo, commercial cargo and passenger ship

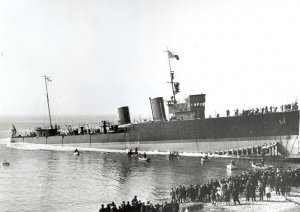

SS Munargo was a commercial cargo and passenger ship built for the Munson Steamship Lines by New York Shipbuilding Corp., Camden, New Jersey launched 17 September 1921. Munargo operated for the line in the New York-Bahamas-Cuba-Miami service passenger cargo trade. In June 1930 the United States and Mexican soccer teams took passage aboard Munargo from New York to Uruguay for the 1930 FIFA World Cup. The ship was acquired by the War Shipping Administration and immediately purchased by the War Department for service as a troop carrier during World War II. Shortly after acquisition the War Department transferred the ship to the U.S. Navy which commissioned the ship USS Munargo (AP-20). She operated in the Atlantic Ocean for the Navy until returned to the War Department in 1943 for conversion into the Hospital ship USAHS Thistle.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SS_Munargo_(1921)

1940 – Italian destroyer Borea sunk

Italian destroyer Borea was a Turbine-class destroyer built for the Royal Italian Navy (Regia Marina) during late 1920s. She was named after a northerly wind, Borea, bringing frigid, dry air to the Italian peninsula.

In the evening of September 16, 1940 Borea together with destroyers Aquilone and Turbine was berthed in Benghazi harbor. At 19:30 steamers Maria Eugenia and Gloria Stella escorted by Fratelli Cairoli arrived from Tripoli bringing the total number of vessels present in the harbor to 32.[10] During the night of September 16 and 17, nine Swordfish bombers of 815 Squadron RAF carrying bombs and torpedoes, and six from 819 Squadron RAF armed with mines took off from Illustrious and approximately at 00:30 arrived undetected over Benghazi harbor. The anti-aircraft defenses opened fire but were unable to stop the attack. After passing over the harbor to determine their targets, Swordfish bombers made their first attack at 00:57 hitting and sinking Gloria Stella and severely damaging torpedo boat Cigno, harbor tug Salvatore Primo and an auxiliary vessel Giuliana. The bombers then conducted a second assault at 1:00 striking and sinking Maria Eugenia. Borea was also targeted during the second sweep, with the first bomb exploding between the destroyer and the steamer Città di Livorno but causing no damage to either ship. A short while later, a second bomb hit Borea on her port side, around 40/39 mm cannon platform. The bomb penetrated all the way down into the hold and exploded breaking the ship in two causing rapid flooding and sinking in shallow waters of the harbor. Due to rapid sinking most of the crew was able to easily abandon ship either by jumping or simply walking off the bridge and swimming towards destroyer Aquilone. There was a single casualty, a sailor who at the moment of the attack was sleeping in the engine room, near the area of bomb explosion.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Italian_destroyer_Borea_(1927)