Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

18 November 1800 - HMS Leda launched at Chatham. The first of the largest class of sailing frigates ever built for the Royal Navy.

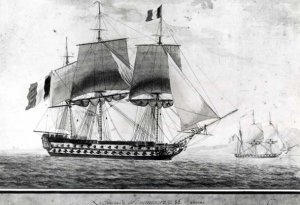

MS Leda, launched in 1800, was the lead ship of a successful class of forty-seven British Royal Navy 38-gun sailing frigates. Leda's design was based on the French Hébé, which the British had captured in 1782. (Hébé herself was the name vessel for the French Hébé-class frigates. Hébé, therefore, has the rare distinction of being the model for both a French and a British frigate class.) Leda was wrecked at the mouth of Milford Haven in 1808, Capt Honeyman was exonerated of all blame, as it was a pilot error.

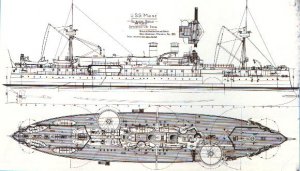

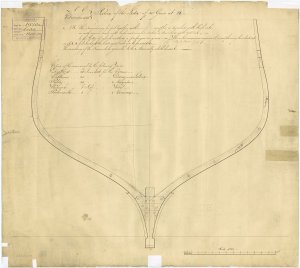

Scale: 1:48. Plan showing the body plan, sheer lines, and longitudinal half-breadth for 'Leda' (1800)

Read more at http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/84700.html#1MlB17rIAvmX9Mqt.99

Class and type: Leda-class frigate

Tons burthen: 107111⁄94 (bm)

Length:

Depth of hold: 12 ft 9 in (3.89 m)

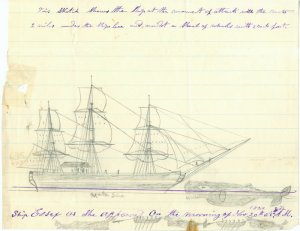

Sail plan: Full-rigged ship

Complement: 284 (later 300);

Armament:

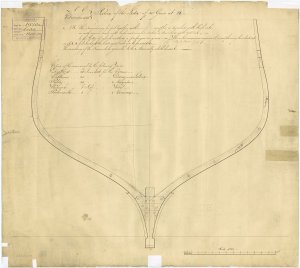

Scale: 1:48. Plan showing the framing profile (disposition) for 'Leda' (1800), a 38-gun Fifth Rate, Frigate, building at Chatham Dockyard.

French Revolutionary Wars

Captain George Johnstone Hope commissioned Leda in November 1800. In 1801 he sailed her in the English Channel and to the coast of Egypt.

On 12 March 1801, Leda recaptured Bolton, Captain Watson, a 20-gun letter of marque that had sailed from Demerara to Liverpool some 6 weeks previously in company with Union and Dart. These two vessels were also letters of marque, all carrying valuable cargoes of sugar, coffee, indigo and cotton. During the voyage Union started to take on water so her crew transferred to Bolton. Then Bolton and Dart parted company in a gale. Next, Bolton had the misfortune to meet the French privateer Gironde, which was armed with 26 guns and had a crew of 260 men. Gironde captured Bolton in an hour-long fight that killed two passengers and wounded Watson and five men. Although Gironde was damaged, she had suffered no casualties. Bolton was also carrying ivory, a tiger, and a large collection of birds, monkeys, and the like.

Then on 5 April Leda captured the French ship Desiree, of eight men and 70 tons. She was sailing from Bordeaux to Brell with a cargo of wheat. Four days later Leda recaptured the Portuguese ship Cæsar, of 10 men and 100 tons. Cæsar had been sailing from Bristol to Lisbon with a cargo of sundries when the French privateer Laura had captured her.

Lastly, on 1 May, Leda captured the French privateer Jupiter. Jupiter, of 90 tons, was armed with 16 guns and had a crew of 60 men. She was from Morlaix on cruise. On the same day Leda recaptured the Portuguese vessel Tejo. Then on 2 September Leda captured Venturose.

Because Leda served in the navy's Egyptian campaign (8 March to 8 September 1801), her officers and crew qualified for the clasp "Egypt" to the Naval General Service Medal that the Admiralty issued in 1847 to all surviving claimants.

In September 1802 Leda came under the command of Captain John (or James) Hardy.

Napoleonic Wars

Captain Robert Honyman (or Honeyman) recommissioned Leda in August 1803 for the North Sea. he would remain her captain until her loss in 1808. Still, at various times Leda was under the temporary command of Captain Henry Digby in 1804 and Captain John Hartley in February 1805.

In 1803 Leda was in the Channel. When the war with France recommenced, Honeyman was put in charge of a small squadron of gun-brigs off Boulogne. On 18 May Leda and Amelia detained the Dutch ship Phoenix. The next day Leda captured Bodes Lust.

Five days after that, Leda, Amelia, Raisonable and Gelikheid were in company at the capture of the Dutch ship Twee Vrienden.

On 29 September Honyman and his squadron attacked a division of 26 enemy gun boats. The engagement lasted several hours until the gunboats took refuge off the pier in Boulogne. Honyman wanted to have his bomb vessels engage them, but winds and tide were unfavorable. The next day 25 more French gunboats arrived. However, before they could join the division that had arrived the night before, the British were able to drive two on shore where they were wrecked. The British suffered no casualties or material damage though a shell did explode in Leda's hold. Fortunately, this did little damage and caused no casualties.

On 21 October Honyman sighted a convoy of six French sloops, some armed, under the escort of a gun-brig. He sent Harpy and Lark to pursue them but the winds were uncooperative and the squadron was unable to engage. Instead, the hired armed cutter Admiral Mitchell, which had only 35 men and twelve 12-pounder carronades, came up and attacked the convoy. After two and a half hours of cannonading, Admiral Mitchell succeeded in driving one sloop and the brig, which was armed with twelve 32-pounder guns, on the rocks. Admiral Mitchell had one gun dismounted, suffered damage to her mast and rigging, and had five men wounded, two seriously.

At the end of July 1804, a boarding party under Lieutenant M'Lean took Leda's boats to mount an unsuccessful attack on a French gunvessel in Boulogne Roads. The attackers succeeded in capturing their target, but the strong tide prevented them from retrieving her. Casualties were heavy in the cutting out party and M'Lean was among the dead; in all, only 14 out of the 38 men in the boarding party returned to Leda.

Early in the morning of 24 April 1805, Leda, again under Honyman's command after Hartley's temporary command, sighted twenty-six French vessels rounding Cap Gris Nez. Honyman immediately ordered Fury, Harpy, Railleur, Bruiser, Gallant, Archer, Locust, Tickler, Watchful, Monkey, Firm and Starling to intercept. After a fight of about two hours, Starling and Locust had captured seven armed schuyts in an action within pistol-shot of the shore batteries on Cap Gris Nez. The schuyts were all of 25 to 28 tons burthen, and carried in all 117 soldiers and 43 seamen under the command of officers from the 51st. Infantry Regiment. The French convoy had been bound for Ambleteuse from Dunkirk. On the British side the only casualty was one man wounded on Archer.

The next day Archer brought in two more schuyts, each armed with one 24-pounder and two 12-pounders. On 25 April 1805 Railleur towed eight of the French schuyts into the Downs. Starling, which had received a great deal of damage, followed Railleur in.

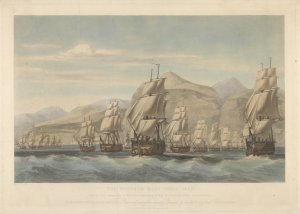

Leda was one of the escorts to a convoy of transports and EIC vessels that were part of the expedition under General Sir David Baird and Admiral Sir Home Riggs Popham that would in 1806 capture the Dutch Cape Colony. They would carry supplies and troops to the Cape, and then continue on their voyages.

At 3:30a.m. on 1 November, near Rocas Atoll Leda sighted breakers and fired a gun, the signal to tack, herself barely missing the danger. King George was unable to tack and wrecked. As Britannia was on the point of tacking she ran afoul of Streatham and lost her bowsprit and foretopmast. She then drifted on to the atoll where she lost her rudder and bilged. In the morning Leda was able to rescue the survivors from King George and Comet, Europe, and Varuna sent their boats and were able to rescue about 400 people from Britannia, including Captain Brisk, his crew, and recruits for the EIC's armies.

The British fleet, including Leda, arrived in Table Bay on 5 January 1806 and anchored off Robben Island. Leda supported the landing of the troops.

On 6 January 1807 Leda was in company with Pheasant and Daphne at the capture of Ann, Denning, master. Leda shared in the capture of the Rolla on 21 February. On 4 March she was at Table Bay and in sight when Diademcaptured the French frigate Volontaire and the two transports that Volontaire was escorting, which turned out to be two British transports that the frigate had captured in the Bay of Biscay, together with the British troops on board. On 19 March the squadron captured the General Izidro.

In June 1810 the prize money for the capture of the Cape of Good Hope was payable. Then in July 1810 there was further distribution of money for the capture of Volontaire and Rolla. In December 1810 prize money for General Izidro was payable.

Leda then accompanied Home Popham across the Atlantic for his expedition to the River Plate. On 9 September 1806 Leda pursued a brigantine on her way to Montevideo until the brigantine's crew beached her. Leda then sent her boats to retrieve or destroy the brigantine. However, when the boarding party reached the brigantine they discovered that her crew had already abandoned her. They also found that she was unarmed, though pierced for 14 guns. Because of the heavy seas the boarding party could not retrieve the brigantine, or even burn her. Instead they simply set her adrift among the breakers. During the operation small arms fire from the shore wounded four men.

Leda remained in South America until the final British evacuation in about September 1807. On 22 August she was in sight, together with a number of other warships, when Procris captured Minerva. Leda then returned to Sheerness and served in the Channel.

At eight o'clock on the morning of 4 December, some 4 leagues (19 km) off Cap de Caux, Leda sighted a privateer lugger making for the French coast, as well as a brig that appeared to be her prize. The brig ran for Havre de Grace but the lugger sailed in another direction as Leda pursued her. After six hours Leda succeeded in capturing the lugger, which turned out to be the brand new vessel Adolphe, under the command of Nicholas Famenter. Adolphe was armed with ten 18-pound carronades, four 4-pounder guns, two 2-pounder guns and two swivel guns. She was eight days out of Boulogne. She had only 25 men on board as she had already put another 45 men of her crew on prizes. She ran ashore on the Bemberg Ledge and it was unlikely she would be gotten off.

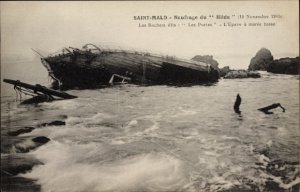

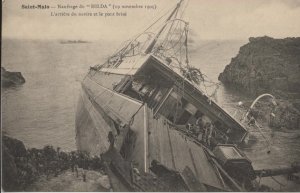

Loss

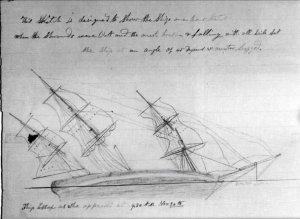

On 31 January 1808, Leda was caught in a gale that did much damage to the ship. Honeyman decided to try to take refuge at Milford Haven but she was wrecked at the mouth of the harbour. The quarantine master for the port came aboard Leda to urge her abandonment. The entire crew was able to get off safely.

A court martial held on board the HMS Salvador del Mundo in the Hamoaze acquitted Honeyman and his crew of all blame. It found that the pilot, James Garretty, had laid a wrong course after mistaking Thorn Island for the Stack Rocks, a mistake that was due to the bad weather and poor visibility.

The Leda-class frigates, were a successful class of forty-seven British Royal Navy 38-gun sailing frigates constructed from 1805-1832. Based on a French design, the class came in five major groups, all with minor differences in their design. During their careers, they fought in the Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812. Forty-five of the 47 were eventually scrapped; two still exist

HMS Trincomalee in the historic dockyard, Hartlepool.

Scale: 1:48. Plan showing the section at Station 25 illustrating the scarph joints of the framing for Leda (1800), and copies later used for Venus (1820), Diana (1822), Latona (1821), Melampus (1820), Hebe (1826), and Minerva (1820), all 38-gun Fifth Rate, Frigates. Signed by Robert Seppings [Surveyor of the Navy, 1813-1832].

Scale: 1:24. Plan showing the midship section for Leda (1800), with copies sent to the various dockyards for Venus (1820), Diana (1822), Latona (1821), Melampus (1820), Hebe (1826), and Minerva (1820), all 38-gun Fifth Rate Frigates. Signed by Robert Seppings [Surveyor of the Navy, 1813-1832].

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Leda_(1800)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leda-class_frigate

18 November 1800 - HMS Leda launched at Chatham. The first of the largest class of sailing frigates ever built for the Royal Navy.

MS Leda, launched in 1800, was the lead ship of a successful class of forty-seven British Royal Navy 38-gun sailing frigates. Leda's design was based on the French Hébé, which the British had captured in 1782. (Hébé herself was the name vessel for the French Hébé-class frigates. Hébé, therefore, has the rare distinction of being the model for both a French and a British frigate class.) Leda was wrecked at the mouth of Milford Haven in 1808, Capt Honeyman was exonerated of all blame, as it was a pilot error.

Scale: 1:48. Plan showing the body plan, sheer lines, and longitudinal half-breadth for 'Leda' (1800)

Read more at http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/84700.html#1MlB17rIAvmX9Mqt.99

Class and type: Leda-class frigate

Tons burthen: 107111⁄94 (bm)

Length:

- 150 ft 2 in (45.77 m) (gundeck)

- 125 ft 4 in (38.20 m) (keel)

Depth of hold: 12 ft 9 in (3.89 m)

Sail plan: Full-rigged ship

Complement: 284 (later 300);

Armament:

- Upper deck: 28 x 18-pounder guns

- QD: 8 x 9-pounder guns + 6 x 32-pounder carronades

- Fc: 2 x 9-pounder guns + 2 x 32-pounder carronades

Scale: 1:48. Plan showing the framing profile (disposition) for 'Leda' (1800), a 38-gun Fifth Rate, Frigate, building at Chatham Dockyard.

French Revolutionary Wars

Captain George Johnstone Hope commissioned Leda in November 1800. In 1801 he sailed her in the English Channel and to the coast of Egypt.

On 12 March 1801, Leda recaptured Bolton, Captain Watson, a 20-gun letter of marque that had sailed from Demerara to Liverpool some 6 weeks previously in company with Union and Dart. These two vessels were also letters of marque, all carrying valuable cargoes of sugar, coffee, indigo and cotton. During the voyage Union started to take on water so her crew transferred to Bolton. Then Bolton and Dart parted company in a gale. Next, Bolton had the misfortune to meet the French privateer Gironde, which was armed with 26 guns and had a crew of 260 men. Gironde captured Bolton in an hour-long fight that killed two passengers and wounded Watson and five men. Although Gironde was damaged, she had suffered no casualties. Bolton was also carrying ivory, a tiger, and a large collection of birds, monkeys, and the like.

Then on 5 April Leda captured the French ship Desiree, of eight men and 70 tons. She was sailing from Bordeaux to Brell with a cargo of wheat. Four days later Leda recaptured the Portuguese ship Cæsar, of 10 men and 100 tons. Cæsar had been sailing from Bristol to Lisbon with a cargo of sundries when the French privateer Laura had captured her.

Lastly, on 1 May, Leda captured the French privateer Jupiter. Jupiter, of 90 tons, was armed with 16 guns and had a crew of 60 men. She was from Morlaix on cruise. On the same day Leda recaptured the Portuguese vessel Tejo. Then on 2 September Leda captured Venturose.

Because Leda served in the navy's Egyptian campaign (8 March to 8 September 1801), her officers and crew qualified for the clasp "Egypt" to the Naval General Service Medal that the Admiralty issued in 1847 to all surviving claimants.

In September 1802 Leda came under the command of Captain John (or James) Hardy.

Napoleonic Wars

Captain Robert Honyman (or Honeyman) recommissioned Leda in August 1803 for the North Sea. he would remain her captain until her loss in 1808. Still, at various times Leda was under the temporary command of Captain Henry Digby in 1804 and Captain John Hartley in February 1805.

In 1803 Leda was in the Channel. When the war with France recommenced, Honeyman was put in charge of a small squadron of gun-brigs off Boulogne. On 18 May Leda and Amelia detained the Dutch ship Phoenix. The next day Leda captured Bodes Lust.

Five days after that, Leda, Amelia, Raisonable and Gelikheid were in company at the capture of the Dutch ship Twee Vrienden.

On 29 September Honyman and his squadron attacked a division of 26 enemy gun boats. The engagement lasted several hours until the gunboats took refuge off the pier in Boulogne. Honyman wanted to have his bomb vessels engage them, but winds and tide were unfavorable. The next day 25 more French gunboats arrived. However, before they could join the division that had arrived the night before, the British were able to drive two on shore where they were wrecked. The British suffered no casualties or material damage though a shell did explode in Leda's hold. Fortunately, this did little damage and caused no casualties.

On 21 October Honyman sighted a convoy of six French sloops, some armed, under the escort of a gun-brig. He sent Harpy and Lark to pursue them but the winds were uncooperative and the squadron was unable to engage. Instead, the hired armed cutter Admiral Mitchell, which had only 35 men and twelve 12-pounder carronades, came up and attacked the convoy. After two and a half hours of cannonading, Admiral Mitchell succeeded in driving one sloop and the brig, which was armed with twelve 32-pounder guns, on the rocks. Admiral Mitchell had one gun dismounted, suffered damage to her mast and rigging, and had five men wounded, two seriously.

At the end of July 1804, a boarding party under Lieutenant M'Lean took Leda's boats to mount an unsuccessful attack on a French gunvessel in Boulogne Roads. The attackers succeeded in capturing their target, but the strong tide prevented them from retrieving her. Casualties were heavy in the cutting out party and M'Lean was among the dead; in all, only 14 out of the 38 men in the boarding party returned to Leda.

Early in the morning of 24 April 1805, Leda, again under Honyman's command after Hartley's temporary command, sighted twenty-six French vessels rounding Cap Gris Nez. Honyman immediately ordered Fury, Harpy, Railleur, Bruiser, Gallant, Archer, Locust, Tickler, Watchful, Monkey, Firm and Starling to intercept. After a fight of about two hours, Starling and Locust had captured seven armed schuyts in an action within pistol-shot of the shore batteries on Cap Gris Nez. The schuyts were all of 25 to 28 tons burthen, and carried in all 117 soldiers and 43 seamen under the command of officers from the 51st. Infantry Regiment. The French convoy had been bound for Ambleteuse from Dunkirk. On the British side the only casualty was one man wounded on Archer.

The next day Archer brought in two more schuyts, each armed with one 24-pounder and two 12-pounders. On 25 April 1805 Railleur towed eight of the French schuyts into the Downs. Starling, which had received a great deal of damage, followed Railleur in.

Leda was one of the escorts to a convoy of transports and EIC vessels that were part of the expedition under General Sir David Baird and Admiral Sir Home Riggs Popham that would in 1806 capture the Dutch Cape Colony. They would carry supplies and troops to the Cape, and then continue on their voyages.

At 3:30a.m. on 1 November, near Rocas Atoll Leda sighted breakers and fired a gun, the signal to tack, herself barely missing the danger. King George was unable to tack and wrecked. As Britannia was on the point of tacking she ran afoul of Streatham and lost her bowsprit and foretopmast. She then drifted on to the atoll where she lost her rudder and bilged. In the morning Leda was able to rescue the survivors from King George and Comet, Europe, and Varuna sent their boats and were able to rescue about 400 people from Britannia, including Captain Brisk, his crew, and recruits for the EIC's armies.

The British fleet, including Leda, arrived in Table Bay on 5 January 1806 and anchored off Robben Island. Leda supported the landing of the troops.

On 6 January 1807 Leda was in company with Pheasant and Daphne at the capture of Ann, Denning, master. Leda shared in the capture of the Rolla on 21 February. On 4 March she was at Table Bay and in sight when Diademcaptured the French frigate Volontaire and the two transports that Volontaire was escorting, which turned out to be two British transports that the frigate had captured in the Bay of Biscay, together with the British troops on board. On 19 March the squadron captured the General Izidro.

In June 1810 the prize money for the capture of the Cape of Good Hope was payable. Then in July 1810 there was further distribution of money for the capture of Volontaire and Rolla. In December 1810 prize money for General Izidro was payable.

Leda then accompanied Home Popham across the Atlantic for his expedition to the River Plate. On 9 September 1806 Leda pursued a brigantine on her way to Montevideo until the brigantine's crew beached her. Leda then sent her boats to retrieve or destroy the brigantine. However, when the boarding party reached the brigantine they discovered that her crew had already abandoned her. They also found that she was unarmed, though pierced for 14 guns. Because of the heavy seas the boarding party could not retrieve the brigantine, or even burn her. Instead they simply set her adrift among the breakers. During the operation small arms fire from the shore wounded four men.

Leda remained in South America until the final British evacuation in about September 1807. On 22 August she was in sight, together with a number of other warships, when Procris captured Minerva. Leda then returned to Sheerness and served in the Channel.

At eight o'clock on the morning of 4 December, some 4 leagues (19 km) off Cap de Caux, Leda sighted a privateer lugger making for the French coast, as well as a brig that appeared to be her prize. The brig ran for Havre de Grace but the lugger sailed in another direction as Leda pursued her. After six hours Leda succeeded in capturing the lugger, which turned out to be the brand new vessel Adolphe, under the command of Nicholas Famenter. Adolphe was armed with ten 18-pound carronades, four 4-pounder guns, two 2-pounder guns and two swivel guns. She was eight days out of Boulogne. She had only 25 men on board as she had already put another 45 men of her crew on prizes. She ran ashore on the Bemberg Ledge and it was unlikely she would be gotten off.

Loss

On 31 January 1808, Leda was caught in a gale that did much damage to the ship. Honeyman decided to try to take refuge at Milford Haven but she was wrecked at the mouth of the harbour. The quarantine master for the port came aboard Leda to urge her abandonment. The entire crew was able to get off safely.

A court martial held on board the HMS Salvador del Mundo in the Hamoaze acquitted Honeyman and his crew of all blame. It found that the pilot, James Garretty, had laid a wrong course after mistaking Thorn Island for the Stack Rocks, a mistake that was due to the bad weather and poor visibility.

The Leda-class frigates, were a successful class of forty-seven British Royal Navy 38-gun sailing frigates constructed from 1805-1832. Based on a French design, the class came in five major groups, all with minor differences in their design. During their careers, they fought in the Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812. Forty-five of the 47 were eventually scrapped; two still exist

HMS Trincomalee in the historic dockyard, Hartlepool.

Scale: 1:48. Plan showing the section at Station 25 illustrating the scarph joints of the framing for Leda (1800), and copies later used for Venus (1820), Diana (1822), Latona (1821), Melampus (1820), Hebe (1826), and Minerva (1820), all 38-gun Fifth Rate, Frigates. Signed by Robert Seppings [Surveyor of the Navy, 1813-1832].

Scale: 1:24. Plan showing the midship section for Leda (1800), with copies sent to the various dockyards for Venus (1820), Diana (1822), Latona (1821), Melampus (1820), Hebe (1826), and Minerva (1820), all 38-gun Fifth Rate Frigates. Signed by Robert Seppings [Surveyor of the Navy, 1813-1832].

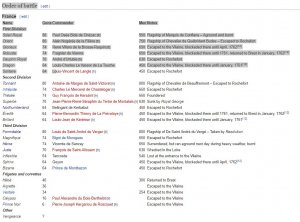

- Leda class 38-gun fifth rates 1800-19, built to the lines of the French Hébé of 1782.

- HMS Leda 1800 - wrecked at the mouth of Milford Haven on 31 January 1808.

- HMS Pomone 1805 - wrecked on the Needles on 14 October 1811.

- HMS Shannon 1806 - hulked as receiving ship at Sheerness in 1831, renamed Saint Lawrence in 1844, broken up 1859.

- HMS Leonidas 1807 - hulked as powder hulk at Sheerness in 1872, sold 1894.

- HMS Briton 1812 - hulked as convict ship at Portsmouth in 1841, broken up 1860.

- HMS Surprise 1812 - hulked as convict ship at Cork in 1822, sold 1837.

- HMS Tenedos 1812 - hulked as convict ship at Bermuda in 1843, converted to accommodation ship in 1863, broken up 1875.

- HMS Lacedemonian 1812 - broken up 1822.

- HMS Lively 1813 - hulked as receiving ship 1831, sold 1863.

- HMS Diamond 1816 - accidentally burnt at Portsmouth on 18 April 1827.

- HMS Amphitrite 1816 - razeed to a 26-gun corvette, transferred to the Coast Guard in 1857.

- HMS Trincomalee 1817 - Teak built, cut down to a 26-gun corvette in 1847, hulked as training ship for volunteers at Sunderland in 1861, sold 1897 to Wheatley Cobb at Falmouth, became training ship Foudroyant, still afloat as museum ship under her original name at Hartlepool.

- HMS Thetis 1817 - wrecked off Cape Frio, Brazil, on 5 December 1830.

- HMS Arethusa 1817 - hulked as lazaretto at Liverpool in 1836, renamed Bacchus in 1844, transferred to Plymouth in 1850, and transformed to coal depot in 1852, sold for breaking in 1883.

- HMS Blanche 1819 - hulked as receiving ship at Portsmouth in 1833, sold for breaking in 1865.

- HMS Fisgard 1819 - hulked as harbour flagship at Woolwich in 1847, broken up 1879.

- modified Leda class 46-gun fifth rates 1820-30

- HMS Venus 1820 - hulked and lent to the Marine Society in 1848, broken up 1865.

- HMS Melampus 1820 - transferred to the Coastguard at Southampton in 1857, returned to the Navy at Portsmouth in 1866, used as an ordnance store for the War Office until 1891, sold 1906.

- HMS Minerva 1820 - broken up 1895.

- HMS Latona 1821 - hulked as mooring vessel at Sheerness in 1868, powder depot at Portsmouth in 1872, broken up 1875.

- HMS Nereus 1821 - hulked as coal depot at Valparaiso in 1843, sold 1879.

- HMS Diana 1822 - hulked as receiving ship at Sheerness in 1868, broken up 1874.

- HMS Hebe 1826 - hulked as receiving ship at Woolwich in 1839, transferred to Sheerness for breaking in 1872.

- HMS Hamadryad 1823 - hulked as hospital ship at Cardiff in 1866, sold 1905.

- HMS Amazon 1821 - cut down to a 26-gun corvette in 1845, sold 1863.

- HMS Aeolus (or Eolus) 1825 - hulked as stores depot at Sheerness in 1846, transferred to Portsmouth as accommodation ship in 1855, transformed into a lazaretto in 1761, broken up in 1886.

- HMS Thisbe 1824 - hulked as floating church at Cardiff 1863, sold 1892.

- HMS Cerberus 1827 - broken up 1866.

- HMS Circe 1827 - hulked as accommodation ship 1866, swimming bath 1885, renamed Impregnable IV, sold for breaking in 1922.

- HMS Clyde 1827 - hulked as RNR training ship at Aberdeen in 1870, sold 1904.

- HMS Thames 1823 - hulked as convict ship at Deptford in 1841, transferred to Bermuda in 1844, sunk in 1863, wreck subsequently sold for breaking.

- HMS Fox 1829 - converted to screw propulsion in 1856, broken up 1882.

- HMS Unicorn 1824 - never fitted for sea, hulked as training ship for the RNR at Dundee in 1860 and still afloat there as museum ship.

- HMS Daedalus 1826 - cut down to a corvette in 1844, hulked as training ship for the RNR at Bristol in 1861, sold for breaking in 1911.

- HMS Proserpine 1830 - sold 1864.

- HMS Mermaid 1825 - hulked as Army powder ship at Purfleet in 1858, returned to the Navy and used as a powder depot at Dublin in 1863, bruken up 1875.

- HMS Mercury 1826 - hulked as coal depot at Woolwich in 1862, transferred to Sheerness in 1873, sold 1906.

- HMS Penelope 1829 - converted to paddle frigate in 1843, sold 1864.

- HMS Thalia 1830 - hulked as Roman Catholic chapel ship at Portsmouth in 1855, broken up 1867.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Leda_(1800)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leda-class_frigate

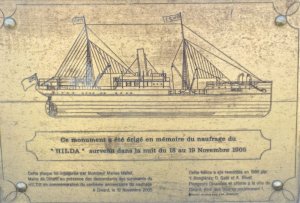

Last edited: