Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

24 April 1913 – Launch of Caio Duilio, an Italian Andrea Doria-class battleship that served in the Regia Marina during World War I and World War II

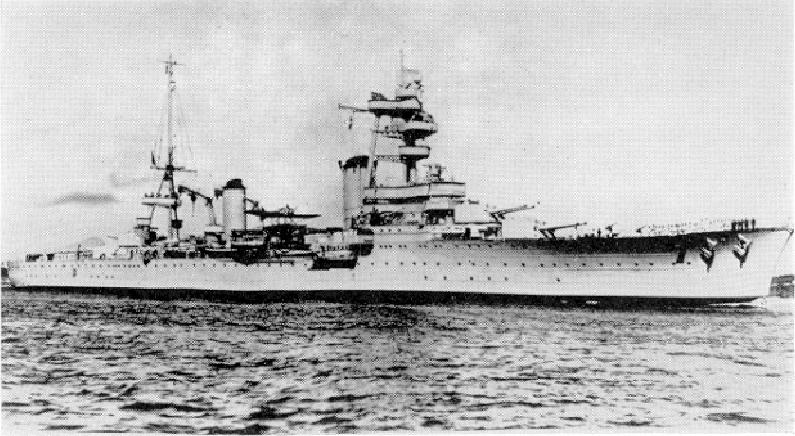

Caio Duilio was an Italian Andrea Doria-class battleship that served in the Regia Marina during World War I and World War II. She was named after the Roman fleet commander Gaius Duilius. Caio Duilio was laid down in February 1912, launched in April 1913, and completed in May 1916. She was initially armed with a main battery of thirteen 305 mm (12.0 in) guns, but a major reconstruction in the late 1930s replaced these with ten 320 mm (13 in) guns. Caio Duilio saw no action during World War I owing to the inactivity of the Austro-Hungarian fleet during the conflict. She cruised the Mediterranean in the 1920s and was involved in the Corfu incident in 1923.

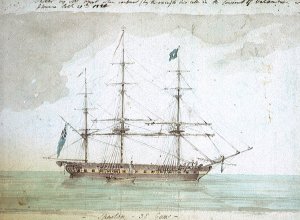

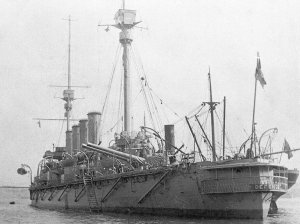

Italian battleship Caio Duilio in 1948.

During World War II, she participated in numerous patrols and sorties into the Mediterranean, both to escort Italian convoys to North Africa and in attempts to catch the British Mediterranean Fleet. In November 1940, the British launched an air raid on Taranto; Caio Duilio was hit by one torpedo launched by a Fairey Swordfish torpedo bomber, which caused significant damage. Repairs lasted some five months, after which the ship returned to convoy escort duties. A fuel shortage immobilized the bulk of the Italian surface fleet in 1942, and Caio Duilio remained out of service until the Italian surrender in September 1943. She was thereafter interned at Malta until 1944, when the Allies permitted her return to Italian waters. She survived the war, and continued to serve in the post-war Italian navy, primarily as a training ship. Caio Duilio was placed in reserve for a final time in 1953; she remained in the Italian navy's inventory for another three years before she was stricken from the naval register in late 1956 and sold for scrapping the following year.

Design

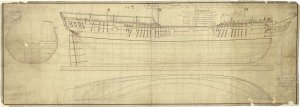

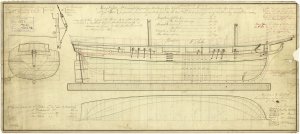

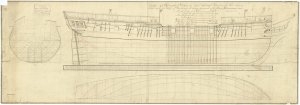

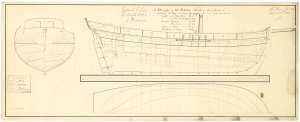

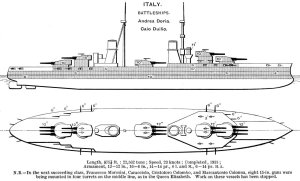

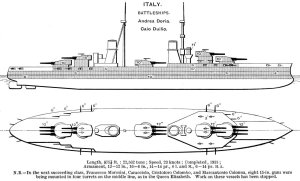

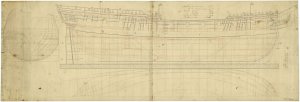

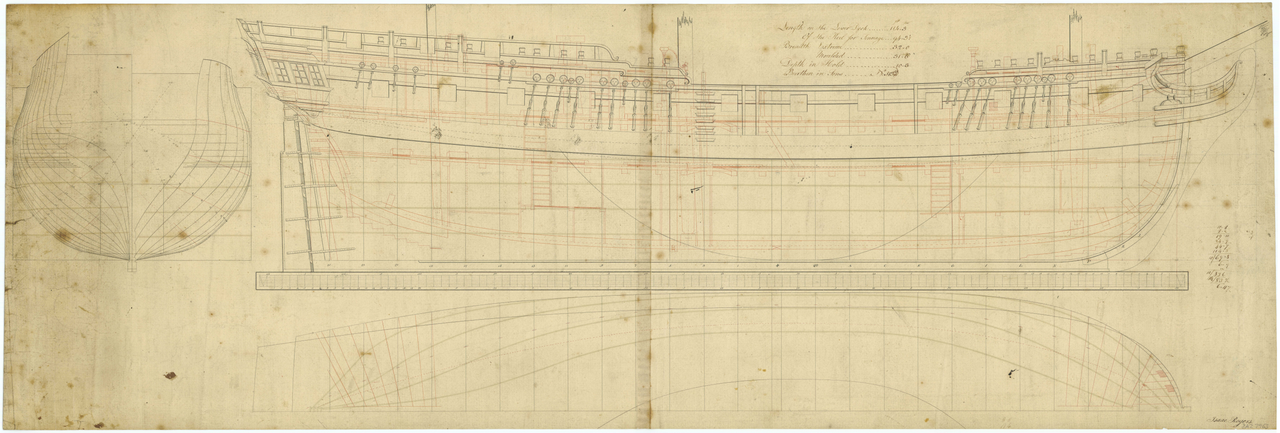

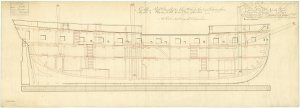

Right elevation and deck plan of the Andrea Doria class.

Main article: Andrea Doria-class battleship

Caio Duilio was 176 meters (577 ft) long overall and had a beam of 28 m (92 ft) and a draft of 9.4 m (31 ft). At full combat load, she displaced up to 24,715 metric tons (24,325 long tons; 27,244 short tons). She had a crew of 35 officers and 1,198 enlisted men. She was powered by four Parsons steam turbines, with steam provided by eight oil-fired and twelve coal and oil burning Yarrow boilers. The boilers were trunked into two large funnels. The engines were rated at 30,000 shaft horsepower (22,000 kW), which provided a top speed of 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph). She had a cruising radius of 4,800 nautical miles (8,900 km; 5,500 mi) at 10 kn (19 km/h; 12 mph).

The ship was armed with a main battery of thirteen 305 mm (12.0 in) 46-caliber guns in three triple turrets and two twin turrets. The secondary battery comprised sixteen 152 mm (6.0 in) 45-caliber guns, all mounted in casemates clustered around the forward and aft main battery turrets. Caio Duilio was also armed with thirteen 76 mm (3.0 in) 50-caliber guns and six 76-mm anti-aircraft guns. As was customary for capital ships of the period, she was equipped with three submerged 450 mm (18 in) torpedo tubes. She was protected with Krupp cemented steel manufactured by U.S. Steel. The belt armor was 254 mm (10.0 in) thick and the main deck was 98 mm (3.9 in) thick. The conning tower and main battery turrets were protected with 280 mm (11 in) worth of armor plating.

Modifications

Caio Duilio was heavily rebuilt in 1937–1940 at Genoa. Her forecastle deck was extended further aft, until it reached the mainmast. The stern and bow were rebuilt, increasing the length of the ship to 186.9 m (613 ft), and the displacement grew to 28,882 t (28,426 long tons; 31,837 short tons). Her old machinery was replaced with more efficient equipment and her twenty boilers were replaced with eight oil-fired models; the new power plant was rated at 75,000 shp (56,000 kW) and speed increased to 26 kn (48 km/h; 30 mph). The ship's amidships turret was removed and the remaining guns were bored out to 320 mm (13 in). Her secondary battery was completely overhauled; the 152 mm guns were replaced with twelve 135 mm (5.3 in) guns in triple turrets amidships. The anti-aircraft battery was significantly improved, to include ten 90 mm (3.5 in) guns, fifteen 37 mm (1.5 in) 54-cal. guns, and sixteen 20 mm (0.79 in) guns. Later, during World War II, four more 37 mm guns were installed and two of the 20 mm guns were removed. After emerging from the modernization, Caio Duilio's crew numbered 35 officers and 1,450 enlisted men

Caio Duilio sailing to Malta for internment, 9 September 1943.

The Andrea Doria class (usually called Caio Duilio class in Italian sources) was a pair of dreadnought battleships built for the Royal Italian Navy (Regia Marina) between 1912 and 1916. The two ships—Andrea Doriaand Caio Duilio—were completed during World War I. The class was an incremental improvement over the preceding Conte di Cavour class. Like the earlier ships, Andrea Doria and Caio Duilio were armed with a main battery of thirteen 305-millimeter (12.0 in) guns.

Andrea Doria during World War I

The two ships were based in southern Italy during World War I to help ensure that the Austro-Hungarian Navy's surface fleet would be contained in the Adriatic. Neither vessel saw any combat during the conflict. After the war, they cruised the Mediterranean and were involved in several international incidents, including at Corfu in 1923. In 1933, both ships were placed in reserve. In 1937 the ships began a lengthy reconstruction. The modifications included removing their center main battery turret and boring out the rest of the guns to 320 mm (12.6 in), strengthening their armor protection, installing new boilers and steam turbines, and lengthening their hulls. The reconstruction work lasted until 1940, by which time Italy was already engaged in World War II.

The two ships were moored in Taranto on the night of 11/12 November 1940 when the British launched a carrier strike on the Italian fleet. In the resulting Battle of Taranto, Caio Duilio was hit by a torpedo and forced to beach to avoid sinking. Andrea Doria was undamaged in the raid; repairs for Caio Duilio lasted until May 1941. Both ships escorted convoys to North Africa in late 1941, including Operation M42, where Andrea Doriasaw action at the inconclusive First Battle of Sirte on 17 December. Fuel shortages curtailed further activities in 1942 and 1943, and both ships were interned at Malta following Italy's surrender in September 1943. Italy was permitted to retain both battleships after the war, and they alternated as fleet flagship until the early 1950s, when they were removed from active service. Both ships were scrapped after 1956.

en.wikipedia.org

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrea_Doria-class_battleship

en.wikipedia.org

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrea_Doria-class_battleship

24 April 1913 – Launch of Caio Duilio, an Italian Andrea Doria-class battleship that served in the Regia Marina during World War I and World War II

Caio Duilio was an Italian Andrea Doria-class battleship that served in the Regia Marina during World War I and World War II. She was named after the Roman fleet commander Gaius Duilius. Caio Duilio was laid down in February 1912, launched in April 1913, and completed in May 1916. She was initially armed with a main battery of thirteen 305 mm (12.0 in) guns, but a major reconstruction in the late 1930s replaced these with ten 320 mm (13 in) guns. Caio Duilio saw no action during World War I owing to the inactivity of the Austro-Hungarian fleet during the conflict. She cruised the Mediterranean in the 1920s and was involved in the Corfu incident in 1923.

Italian battleship Caio Duilio in 1948.

During World War II, she participated in numerous patrols and sorties into the Mediterranean, both to escort Italian convoys to North Africa and in attempts to catch the British Mediterranean Fleet. In November 1940, the British launched an air raid on Taranto; Caio Duilio was hit by one torpedo launched by a Fairey Swordfish torpedo bomber, which caused significant damage. Repairs lasted some five months, after which the ship returned to convoy escort duties. A fuel shortage immobilized the bulk of the Italian surface fleet in 1942, and Caio Duilio remained out of service until the Italian surrender in September 1943. She was thereafter interned at Malta until 1944, when the Allies permitted her return to Italian waters. She survived the war, and continued to serve in the post-war Italian navy, primarily as a training ship. Caio Duilio was placed in reserve for a final time in 1953; she remained in the Italian navy's inventory for another three years before she was stricken from the naval register in late 1956 and sold for scrapping the following year.

Design

Right elevation and deck plan of the Andrea Doria class.

Main article: Andrea Doria-class battleship

Caio Duilio was 176 meters (577 ft) long overall and had a beam of 28 m (92 ft) and a draft of 9.4 m (31 ft). At full combat load, she displaced up to 24,715 metric tons (24,325 long tons; 27,244 short tons). She had a crew of 35 officers and 1,198 enlisted men. She was powered by four Parsons steam turbines, with steam provided by eight oil-fired and twelve coal and oil burning Yarrow boilers. The boilers were trunked into two large funnels. The engines were rated at 30,000 shaft horsepower (22,000 kW), which provided a top speed of 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph). She had a cruising radius of 4,800 nautical miles (8,900 km; 5,500 mi) at 10 kn (19 km/h; 12 mph).

The ship was armed with a main battery of thirteen 305 mm (12.0 in) 46-caliber guns in three triple turrets and two twin turrets. The secondary battery comprised sixteen 152 mm (6.0 in) 45-caliber guns, all mounted in casemates clustered around the forward and aft main battery turrets. Caio Duilio was also armed with thirteen 76 mm (3.0 in) 50-caliber guns and six 76-mm anti-aircraft guns. As was customary for capital ships of the period, she was equipped with three submerged 450 mm (18 in) torpedo tubes. She was protected with Krupp cemented steel manufactured by U.S. Steel. The belt armor was 254 mm (10.0 in) thick and the main deck was 98 mm (3.9 in) thick. The conning tower and main battery turrets were protected with 280 mm (11 in) worth of armor plating.

Modifications

Caio Duilio was heavily rebuilt in 1937–1940 at Genoa. Her forecastle deck was extended further aft, until it reached the mainmast. The stern and bow were rebuilt, increasing the length of the ship to 186.9 m (613 ft), and the displacement grew to 28,882 t (28,426 long tons; 31,837 short tons). Her old machinery was replaced with more efficient equipment and her twenty boilers were replaced with eight oil-fired models; the new power plant was rated at 75,000 shp (56,000 kW) and speed increased to 26 kn (48 km/h; 30 mph). The ship's amidships turret was removed and the remaining guns were bored out to 320 mm (13 in). Her secondary battery was completely overhauled; the 152 mm guns were replaced with twelve 135 mm (5.3 in) guns in triple turrets amidships. The anti-aircraft battery was significantly improved, to include ten 90 mm (3.5 in) guns, fifteen 37 mm (1.5 in) 54-cal. guns, and sixteen 20 mm (0.79 in) guns. Later, during World War II, four more 37 mm guns were installed and two of the 20 mm guns were removed. After emerging from the modernization, Caio Duilio's crew numbered 35 officers and 1,450 enlisted men

Caio Duilio sailing to Malta for internment, 9 September 1943.

The Andrea Doria class (usually called Caio Duilio class in Italian sources) was a pair of dreadnought battleships built for the Royal Italian Navy (Regia Marina) between 1912 and 1916. The two ships—Andrea Doriaand Caio Duilio—were completed during World War I. The class was an incremental improvement over the preceding Conte di Cavour class. Like the earlier ships, Andrea Doria and Caio Duilio were armed with a main battery of thirteen 305-millimeter (12.0 in) guns.

Andrea Doria during World War I

The two ships were based in southern Italy during World War I to help ensure that the Austro-Hungarian Navy's surface fleet would be contained in the Adriatic. Neither vessel saw any combat during the conflict. After the war, they cruised the Mediterranean and were involved in several international incidents, including at Corfu in 1923. In 1933, both ships were placed in reserve. In 1937 the ships began a lengthy reconstruction. The modifications included removing their center main battery turret and boring out the rest of the guns to 320 mm (12.6 in), strengthening their armor protection, installing new boilers and steam turbines, and lengthening their hulls. The reconstruction work lasted until 1940, by which time Italy was already engaged in World War II.

The two ships were moored in Taranto on the night of 11/12 November 1940 when the British launched a carrier strike on the Italian fleet. In the resulting Battle of Taranto, Caio Duilio was hit by a torpedo and forced to beach to avoid sinking. Andrea Doria was undamaged in the raid; repairs for Caio Duilio lasted until May 1941. Both ships escorted convoys to North Africa in late 1941, including Operation M42, where Andrea Doriasaw action at the inconclusive First Battle of Sirte on 17 December. Fuel shortages curtailed further activities in 1942 and 1943, and both ships were interned at Malta following Italy's surrender in September 1943. Italy was permitted to retain both battleships after the war, and they alternated as fleet flagship until the early 1950s, when they were removed from active service. Both ships were scrapped after 1956.

(The Black Bear),

(The Black Bear),

in 1864 of Royal Sovereignafter her conversion into a

in 1864 of Royal Sovereignafter her conversion into a