Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

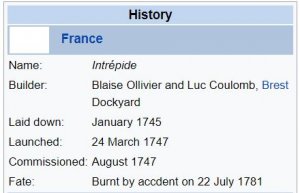

24 March 1747 – Launch of French Intrépide 74 at Brest - burnt by accident in July 1781

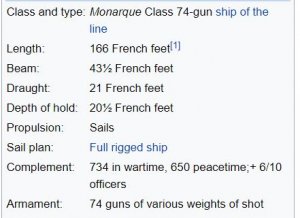

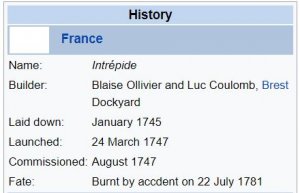

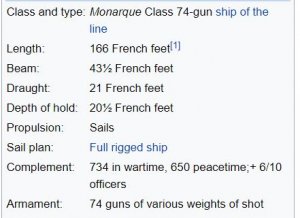

The Intrépide was a 74-gun ship of the line of the French Navy. She was of three ships of the Monarque class, all launched in 1747, the others being the Monarque and the Sceptre.

Design

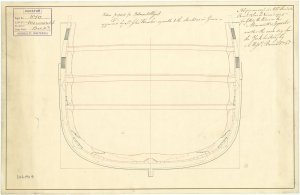

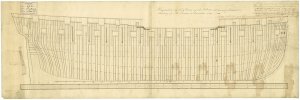

Designed by Blaise Ollivier and built by him until his death in October 1746, then completed by Luc Coulomb, her keel was laid down at Brest on 14 November 1745 towards the end of the War of the Austrian Succession and she was launched on 24 March 1747. The fifth ship of this type to be built by the French Navy, she was designed to the norms set for ships of the line by French shipbuilders in the 1740s to try to match the cost, armament and manouvrability of their British counterparts, since the Royal Navy had had a greater number of ships than the French since the end of the wars of Louis XIV.[3] Without being standardized, dozens of French 74s were based on these norms right up until the start of the 19th century, slowly evolving to match new shipbuilding technologies and the wishes of naval tacticians and strategists.

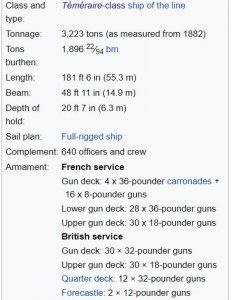

Her 74 guns comprised 28 x 36-pounders on the lower deck, 30 x 18-pounders on the upper deck, 10 x 8-pounders on the quarterdeck and 6 x 8-pounders on the forecastle.

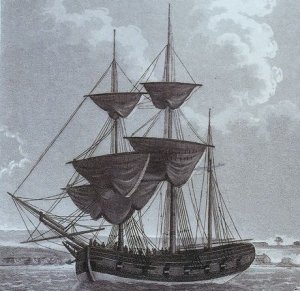

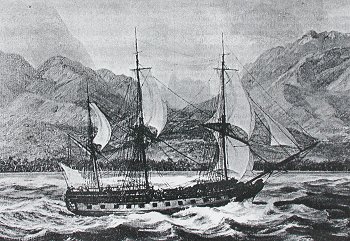

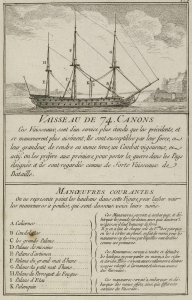

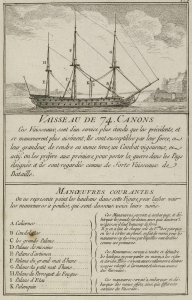

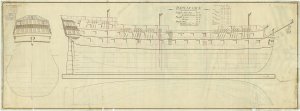

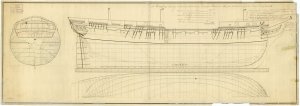

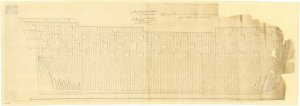

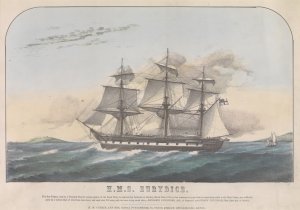

A French 74-gun ship of the same type as the Intrépide, drawn by Nicolas Ozanne.

Service

War of the Austrian Succession

The Intrépide fought at the Second Battle of Cape Finisterre on 25 October 1747, forming part of Henri-François des Herbiers's division, which also included the admiral's flagship the 80-gun Tonnant, the 74-gun Monarque and Terrible, four 56-to-68 gun ships and a 26-gun frigate. They were charged with escorting a convoy of over 250 merchantmen to the Antilles and faced Edward Hawkeand his 14-ship squadron.

The engagement lasted nearly seven hours and saw six French ships captured. Heading the French line and captained by the experienced commander de Vaudreuil, the Intrépide was little damaged, since she was the last ship attacked by the British squadron. She escaped her pursuers and saved the Tonnant, allowing her to disengage. The following dawn the Intrépide managed to take the Tonnant in tow. Their success was not only down to their commanders but also the fact that they were new powerful ships, easier to handle and with more modern armament than older ships in the British and French fleets. They arrived in Brest on 9 November 1747 whilst the convoy safely reached the Antilles.

She was used as the test-bed for an inclining experiment (the first such ever recorded) which was performed in May 1748 by François-Guillaume Clairain-Deslauriers.

The English painter Samuel Scott (1702–1772) specialised in marine painting and views of London. A strong influence of the art of Willem van de Velde the Younger can be detected particularly in his early work. This composition of the large-scale oil painting of Lord Anson's victory off Cape Finisterre, 3 May 1747, bears strong resemblance to Willem van de Velde’s ‘Battle of Texel, 1687’ (BHC0315). In the War of the Austrian Succession, Cape Finisterre was the scene of a naval battle between a British fleet of 14 ships of the line commanded by Sir George Anson, who had recently been promoted to Vice-Admiral of the Blue, and two French squadrons that had not yet parted company to proceed to their separate destinations. One was making for North America for the recovery of Cape Breton Island, the other, together with a convoy, was intended to operate against the British settlements on the Coromandel Coast of India. Viewed on eye level the spectator beholds the action unfolding in the middle distance across the open water. The victorious vessel, Anson’s flagship the ‘Prince George’, can be seen just off stern in the centre of the composition, her sails brightly lit from the right, firing her guns. On either side, set back along the horizon, other ships of the English and the French fleet are engaged in the battle.

Battle of Cape Finisterre (October 1747). "Battle of the ship Intrepid against several British ships"

Seven Years' War

In 1756 the Intrépide was put under the command of Guy François de Kersaint and made the flagship of a fleet charged with capturing all British ships operating off the coast of Guinea. This proved a success and the Intrépide moved to the Antilles, where she was attacked near Caicos on 21 October 1757 by three British ships in the battle of Cap-Français. This lasted several hours and the Intrépide was almost completely dismasted, whilst her captain was wounded twice, though she managed to force the British ships to retreat.

In 1759 she joined a twenty-one ship invasion fleet under maréchal de Conflans. She took part in the battle of Les Cardinaux on 20 November that year under the command of Charles Le Mercerel de Chasteloger, joining the Soleil-Royal in her attack on the British flagship HMS Royal George. On the day after the French defeat the Intrépide and seven other ships left the combat area to take refuge at Rochefort.

The Intrépide subsequently underwent a rebuilding at Brest from 1758 to April 1759, carried out by Léon-Michel Guignace.

American Revolutionary War

From January 1776 to March 1778 the Intrépide was commanded by François Joseph Paul de Grasse. She took part in the Battle of Ushant on 27 July 1778 under the command of Louis-André de Beaussier de Châteauvert in the blue squadron, which formed the French fleet's rearguard and was commanded by Louis-Philippe d'Orléans. In 1780 she joined de Guichen's fleet sent to fight in the Antilles. On 17 April 1780, under the command of Louis Guillaume de Parscau du Plessix, she fought in the battle of Martinique, again in the rearguard. She was finally lost on 22 July 1781 off Cape Français, when a barrel of local rum caught fire and the ship was burned and sunk.

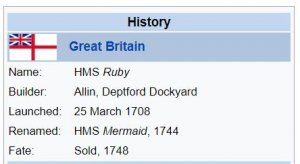

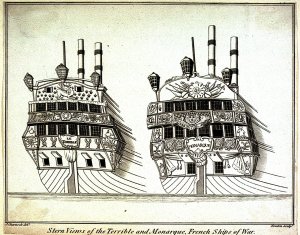

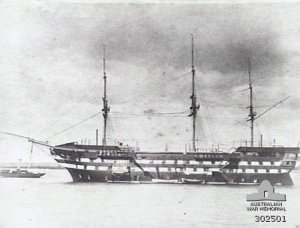

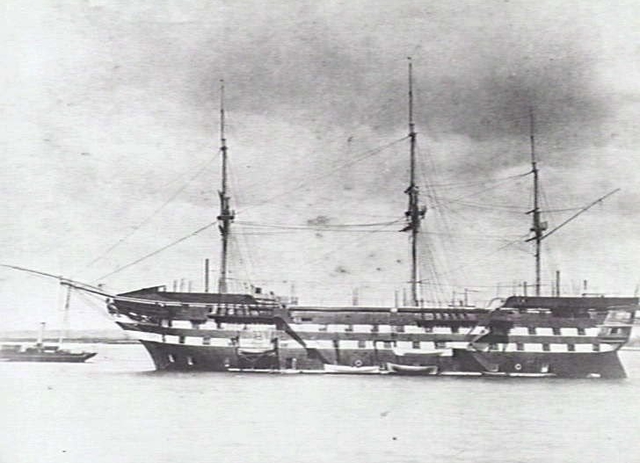

sistership Monarque

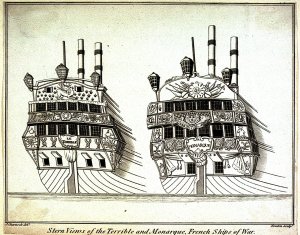

Stern Views of the Terrible and Monarque, French Ships of War (PAD0249)

Monarque Class. Three ships built at Brest to a design by Blaise Ollivier, 1745. Following his death in October 1746, the three ships were completed by Luc Coulomb.

Monarque 74 (launched March 1747 at Brest) – captured by the British in the Second Battle of Cape Finisterre in October 1747

Intrépide 74 (launched 24 March 1747 at Brest) - burnt by accident in July 1781

Sceptre 74 (launched 21 June 1747 at Brest) - hulked at Brest in January 1779

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

24 March 1747 – Launch of French Intrépide 74 at Brest - burnt by accident in July 1781

The Intrépide was a 74-gun ship of the line of the French Navy. She was of three ships of the Monarque class, all launched in 1747, the others being the Monarque and the Sceptre.

Design

Designed by Blaise Ollivier and built by him until his death in October 1746, then completed by Luc Coulomb, her keel was laid down at Brest on 14 November 1745 towards the end of the War of the Austrian Succession and she was launched on 24 March 1747. The fifth ship of this type to be built by the French Navy, she was designed to the norms set for ships of the line by French shipbuilders in the 1740s to try to match the cost, armament and manouvrability of their British counterparts, since the Royal Navy had had a greater number of ships than the French since the end of the wars of Louis XIV.[3] Without being standardized, dozens of French 74s were based on these norms right up until the start of the 19th century, slowly evolving to match new shipbuilding technologies and the wishes of naval tacticians and strategists.

Her 74 guns comprised 28 x 36-pounders on the lower deck, 30 x 18-pounders on the upper deck, 10 x 8-pounders on the quarterdeck and 6 x 8-pounders on the forecastle.

A French 74-gun ship of the same type as the Intrépide, drawn by Nicolas Ozanne.

Service

War of the Austrian Succession

The Intrépide fought at the Second Battle of Cape Finisterre on 25 October 1747, forming part of Henri-François des Herbiers's division, which also included the admiral's flagship the 80-gun Tonnant, the 74-gun Monarque and Terrible, four 56-to-68 gun ships and a 26-gun frigate. They were charged with escorting a convoy of over 250 merchantmen to the Antilles and faced Edward Hawkeand his 14-ship squadron.

The engagement lasted nearly seven hours and saw six French ships captured. Heading the French line and captained by the experienced commander de Vaudreuil, the Intrépide was little damaged, since she was the last ship attacked by the British squadron. She escaped her pursuers and saved the Tonnant, allowing her to disengage. The following dawn the Intrépide managed to take the Tonnant in tow. Their success was not only down to their commanders but also the fact that they were new powerful ships, easier to handle and with more modern armament than older ships in the British and French fleets. They arrived in Brest on 9 November 1747 whilst the convoy safely reached the Antilles.

She was used as the test-bed for an inclining experiment (the first such ever recorded) which was performed in May 1748 by François-Guillaume Clairain-Deslauriers.

The English painter Samuel Scott (1702–1772) specialised in marine painting and views of London. A strong influence of the art of Willem van de Velde the Younger can be detected particularly in his early work. This composition of the large-scale oil painting of Lord Anson's victory off Cape Finisterre, 3 May 1747, bears strong resemblance to Willem van de Velde’s ‘Battle of Texel, 1687’ (BHC0315). In the War of the Austrian Succession, Cape Finisterre was the scene of a naval battle between a British fleet of 14 ships of the line commanded by Sir George Anson, who had recently been promoted to Vice-Admiral of the Blue, and two French squadrons that had not yet parted company to proceed to their separate destinations. One was making for North America for the recovery of Cape Breton Island, the other, together with a convoy, was intended to operate against the British settlements on the Coromandel Coast of India. Viewed on eye level the spectator beholds the action unfolding in the middle distance across the open water. The victorious vessel, Anson’s flagship the ‘Prince George’, can be seen just off stern in the centre of the composition, her sails brightly lit from the right, firing her guns. On either side, set back along the horizon, other ships of the English and the French fleet are engaged in the battle.

Battle of Cape Finisterre (October 1747). "Battle of the ship Intrepid against several British ships"

Seven Years' War

In 1756 the Intrépide was put under the command of Guy François de Kersaint and made the flagship of a fleet charged with capturing all British ships operating off the coast of Guinea. This proved a success and the Intrépide moved to the Antilles, where she was attacked near Caicos on 21 October 1757 by three British ships in the battle of Cap-Français. This lasted several hours and the Intrépide was almost completely dismasted, whilst her captain was wounded twice, though she managed to force the British ships to retreat.

In 1759 she joined a twenty-one ship invasion fleet under maréchal de Conflans. She took part in the battle of Les Cardinaux on 20 November that year under the command of Charles Le Mercerel de Chasteloger, joining the Soleil-Royal in her attack on the British flagship HMS Royal George. On the day after the French defeat the Intrépide and seven other ships left the combat area to take refuge at Rochefort.

The Intrépide subsequently underwent a rebuilding at Brest from 1758 to April 1759, carried out by Léon-Michel Guignace.

American Revolutionary War

From January 1776 to March 1778 the Intrépide was commanded by François Joseph Paul de Grasse. She took part in the Battle of Ushant on 27 July 1778 under the command of Louis-André de Beaussier de Châteauvert in the blue squadron, which formed the French fleet's rearguard and was commanded by Louis-Philippe d'Orléans. In 1780 she joined de Guichen's fleet sent to fight in the Antilles. On 17 April 1780, under the command of Louis Guillaume de Parscau du Plessix, she fought in the battle of Martinique, again in the rearguard. She was finally lost on 22 July 1781 off Cape Français, when a barrel of local rum caught fire and the ship was burned and sunk.

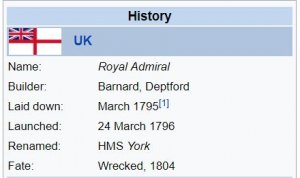

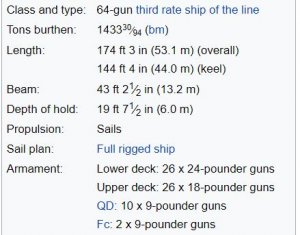

sistership Monarque

Stern Views of the Terrible and Monarque, French Ships of War (PAD0249)

Monarque Class. Three ships built at Brest to a design by Blaise Ollivier, 1745. Following his death in October 1746, the three ships were completed by Luc Coulomb.

Monarque 74 (launched March 1747 at Brest) – captured by the British in the Second Battle of Cape Finisterre in October 1747

Intrépide 74 (launched 24 March 1747 at Brest) - burnt by accident in July 1781

Sceptre 74 (launched 21 June 1747 at Brest) - hulked at Brest in January 1779

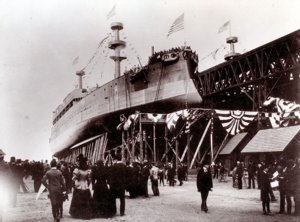

Shipbuilding Company

Shipbuilding Company

bury

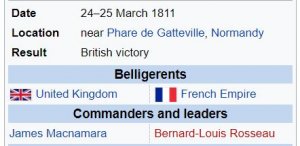

bury