Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

25 October 1799 – The Cutting Out of the Hermione

The Cutting out of the Hermione, or Capture of Hermione, was a naval action that took place at Puerto Cabello, Venezuela on 25 October 1799. The formerly British frigate HMS Hermione, which had been handed over to the Spanish by its crew following a vicious mutiny, lay in the heavily guarded sea port of Puerto Cabello now under the command of Don Ramon de Chalas. A British frigate, HMS Surprise, was sent under Edward Hamilton to recapture Hermione. In naval terms this was called a cutting out operation—a boarding attack by small boats, preferably at night and against an unsuspecting and anchored target. This had become a popular tactic during the later 18th century.

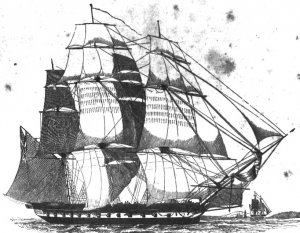

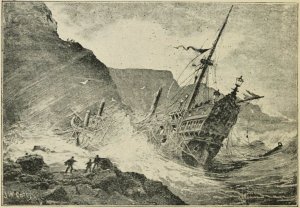

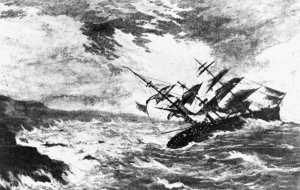

HMS Hermione being cut out of Puerto Cabello by boats from HMS Surprise

Background

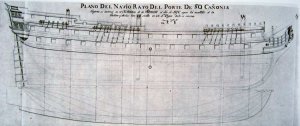

HMS Hermione was a frigate of the Royal Navy, commanded by Captain Hugh Pigot. In September 1797 a number of the crew had risen up against the tyrannical[3] Pigot and had murdered him and nine other officers, throwing their bodies overboard. Fearing retribution for their actions, the mutineers had sailed Hermione to the Spanish port of La Guaira, and handed her over to the Spanish. The mutineers claimed they had set the officers adrift in a small boat, as had happened in the mutiny on Bounty some eight years earlier.

The Spaniards took Hermione into service under the name Santa Cecilia where she remained for two years at La Guaira. Her crew which included 25 of her former crew, remained under Spanish guard.

Meanwhile, news of the fate of Hermione reached Admiral Sir Hyde Parker when HMS Diligence captured a Spanish schooner. Parker wrote to the governor of La Guaira, demanding the return of the ship and the surrender of the mutineers but the governor only moved the ship to Puerto Cabello. Meanwhile Parker dispatched HMS Magicienne under Captain Henry Ricketts to commence negotiations.[4] Parker also set up a system of informers and posted rewards that eventually led to the capture of 33 of the mutineers. eventually reached Parker that Santa Cecilia had been sighted in Puerto Cabello, and ordered HMS Surpriseto intercept her, should she attempt to put to sea.

eventually reached Parker that Santa Cecilia had been sighted in Puerto Cabello, and ordered HMS Surpriseto intercept her, should she attempt to put to sea.

Captain Edward Hamilton of Surprise decided that the honour of the Royal Navy depended on the recovery of the ship, and was determined to retake her.[9] ing near the port he devised a plan to cut her out of the harbour, and asked for a boat and an extra twenty men from Parker. Parker declared the scheme too risky, and refused to send the men, but Hamilton went ahead anyway.

ing near the port he devised a plan to cut her out of the harbour, and asked for a boat and an extra twenty men from Parker. Parker declared the scheme too risky, and refused to send the men, but Hamilton went ahead anyway.

Battle

Santa Cecilia was heavily manned, with around 400 Spanish under the command of Captain Don Ramon de Chalas. She lay under the guns of two shore batteries, together mounting some 200 guns.

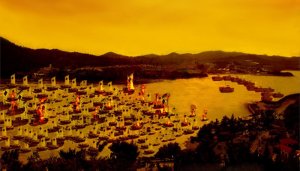

Santa Cecilia being boarded by British marines and sailors in Puerto Cabello

Hamilton had a force of some 100 soldiers, and sailors, in his boats.

Hamilton meticulously planned the capture. The boarding parties were clothed in dark only, with no sign of white or light colours. Each of the boats was placed in a formation of two divisions, and were towed in threes. One division would attack the starboard side while the other was to board the larboard side.[1] Each boat was given as a specific task a part of the ship which they were responsible for securing.

Stealth was a key part of the attack plan, but Hamilton did not achieve this because, as he led his boats for the attack, he was spotted by two Spanish gun-vessels. In addition, some of the boats were caught in a boom, a floating barrier. They soon got free, but this alerted the Spanish shore batteries, which opened fire. With the alarm given, the crew of Santa Cecilia were ready for the British as the boats got alongside her. As the British approached, the Spanish kept up a brisk fire of musketry but fired on their own gun boats as well the attacking British which caused confusion to both sides.

Nevertheless, Santa Cecilia was boarded. Initially, the first party to board was pushed back, and Hamilton was alone on the quarter deck fighting four Spaniards. A musket butt soon knocked him down. At this moment the other division had swung around, and they too boarded the ship. This included the Marines, who, with a single volley, rushed the main deck saving Hamilton. They then charged with the bayonets, driving the Spaniards from the top decks. The Spaniards were then caught in a crossfire, which drove them below deck. The fight continued in the heart of the ship.

As the fight below deck continued, Hamilton's sailors were cutting the cables holding Santa Cecilia at bay, and the sails were loosed to catch the breeze.

Captain de Challas was wounded, captured, and taken below, despite some resistance by a few who tried to take back the ship. The rest of the Spanish surrendered soon after de Challas was captured.

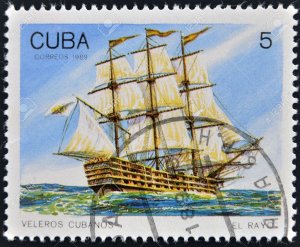

Santa Cecilia is sailed out from Puerto Cabello after being secured - print by Thomas Whitcombe

The batteries surrounding Puerto Cabello opened fire when they saw the ship sailing away, and scored a number of hits on the ship, but no major damage was done. Hamilton ordered no shots to be fired, and no light to be shown; a tactic which worked, as Santa Cecilia sailed out of danger.

By 2:00 a.m. the battle was over and fire from the shore batteries had died down. The boats with Santa Cecilia met up with HMS Surprise by 3:00 a.m.

Aftermath

The Spanish had lost 120 killed, while 231 were taken prisoner, 97 of whom were wounded. All but three including Don Challas and two other officers were subsequently returned to the port the next day. Another fifteen Spanish escaped by jumping overboard and swimming ashore, while 20 more escaped in a launch that had been guarding the ship. By contrast the British had not lost a single man, and had just twelve wounded, four of them seriously. One of them was Hamilton himself, who had suffered a blow to the head from a musket, and wounds from a sabre, pike and grapeshot.

Parker had the recaptured Hermione renamed HMS Retaliation, after which the Admiralty ordered her to be renamed HMS Retribution on 31 January 1800. The prize money was distributed making Hamilton a rich man, so much so that he declined a pension.

For his daring exploit, Hamilton was made a knight by letters patent, a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath (2 January 1815), and eventually became a baronet (20 October 1818). The Jamaica House of Assemblyawarded him a sword worth 300 guineas, and the City of London awarded him the Freedom of the City in a public dinner on 25 October 1800.

In 1847, the Admiralty awarded Hamilton a gold medal for the recapture of Hermione, and the Naval General Service Medal with the clasp, "Surprise with Hermione", to the seven surviving claimants from the action.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cutting_out_of_the_Hermione

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Surprise_(1796)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Hermione_(1782)

25 October 1799 – The Cutting Out of the Hermione

The Cutting out of the Hermione, or Capture of Hermione, was a naval action that took place at Puerto Cabello, Venezuela on 25 October 1799. The formerly British frigate HMS Hermione, which had been handed over to the Spanish by its crew following a vicious mutiny, lay in the heavily guarded sea port of Puerto Cabello now under the command of Don Ramon de Chalas. A British frigate, HMS Surprise, was sent under Edward Hamilton to recapture Hermione. In naval terms this was called a cutting out operation—a boarding attack by small boats, preferably at night and against an unsuspecting and anchored target. This had become a popular tactic during the later 18th century.

HMS Hermione being cut out of Puerto Cabello by boats from HMS Surprise

Background

HMS Hermione was a frigate of the Royal Navy, commanded by Captain Hugh Pigot. In September 1797 a number of the crew had risen up against the tyrannical[3] Pigot and had murdered him and nine other officers, throwing their bodies overboard. Fearing retribution for their actions, the mutineers had sailed Hermione to the Spanish port of La Guaira, and handed her over to the Spanish. The mutineers claimed they had set the officers adrift in a small boat, as had happened in the mutiny on Bounty some eight years earlier.

The Spaniards took Hermione into service under the name Santa Cecilia where she remained for two years at La Guaira. Her crew which included 25 of her former crew, remained under Spanish guard.

Meanwhile, news of the fate of Hermione reached Admiral Sir Hyde Parker when HMS Diligence captured a Spanish schooner. Parker wrote to the governor of La Guaira, demanding the return of the ship and the surrender of the mutineers but the governor only moved the ship to Puerto Cabello. Meanwhile Parker dispatched HMS Magicienne under Captain Henry Ricketts to commence negotiations.[4] Parker also set up a system of informers and posted rewards that eventually led to the capture of 33 of the mutineers.

eventually reached Parker that Santa Cecilia had been sighted in Puerto Cabello, and ordered HMS Surpriseto intercept her, should she attempt to put to sea.

eventually reached Parker that Santa Cecilia had been sighted in Puerto Cabello, and ordered HMS Surpriseto intercept her, should she attempt to put to sea.Captain Edward Hamilton of Surprise decided that the honour of the Royal Navy depended on the recovery of the ship, and was determined to retake her.[9]

ing near the port he devised a plan to cut her out of the harbour, and asked for a boat and an extra twenty men from Parker. Parker declared the scheme too risky, and refused to send the men, but Hamilton went ahead anyway.

ing near the port he devised a plan to cut her out of the harbour, and asked for a boat and an extra twenty men from Parker. Parker declared the scheme too risky, and refused to send the men, but Hamilton went ahead anyway.Battle

Santa Cecilia was heavily manned, with around 400 Spanish under the command of Captain Don Ramon de Chalas. She lay under the guns of two shore batteries, together mounting some 200 guns.

Santa Cecilia being boarded by British marines and sailors in Puerto Cabello

Hamilton had a force of some 100 soldiers, and sailors, in his boats.

Hamilton meticulously planned the capture. The boarding parties were clothed in dark only, with no sign of white or light colours. Each of the boats was placed in a formation of two divisions, and were towed in threes. One division would attack the starboard side while the other was to board the larboard side.[1] Each boat was given as a specific task a part of the ship which they were responsible for securing.

Stealth was a key part of the attack plan, but Hamilton did not achieve this because, as he led his boats for the attack, he was spotted by two Spanish gun-vessels. In addition, some of the boats were caught in a boom, a floating barrier. They soon got free, but this alerted the Spanish shore batteries, which opened fire. With the alarm given, the crew of Santa Cecilia were ready for the British as the boats got alongside her. As the British approached, the Spanish kept up a brisk fire of musketry but fired on their own gun boats as well the attacking British which caused confusion to both sides.

Nevertheless, Santa Cecilia was boarded. Initially, the first party to board was pushed back, and Hamilton was alone on the quarter deck fighting four Spaniards. A musket butt soon knocked him down. At this moment the other division had swung around, and they too boarded the ship. This included the Marines, who, with a single volley, rushed the main deck saving Hamilton. They then charged with the bayonets, driving the Spaniards from the top decks. The Spaniards were then caught in a crossfire, which drove them below deck. The fight continued in the heart of the ship.

As the fight below deck continued, Hamilton's sailors were cutting the cables holding Santa Cecilia at bay, and the sails were loosed to catch the breeze.

Captain de Challas was wounded, captured, and taken below, despite some resistance by a few who tried to take back the ship. The rest of the Spanish surrendered soon after de Challas was captured.

Santa Cecilia is sailed out from Puerto Cabello after being secured - print by Thomas Whitcombe

The batteries surrounding Puerto Cabello opened fire when they saw the ship sailing away, and scored a number of hits on the ship, but no major damage was done. Hamilton ordered no shots to be fired, and no light to be shown; a tactic which worked, as Santa Cecilia sailed out of danger.

By 2:00 a.m. the battle was over and fire from the shore batteries had died down. The boats with Santa Cecilia met up with HMS Surprise by 3:00 a.m.

Aftermath

The Spanish had lost 120 killed, while 231 were taken prisoner, 97 of whom were wounded. All but three including Don Challas and two other officers were subsequently returned to the port the next day. Another fifteen Spanish escaped by jumping overboard and swimming ashore, while 20 more escaped in a launch that had been guarding the ship. By contrast the British had not lost a single man, and had just twelve wounded, four of them seriously. One of them was Hamilton himself, who had suffered a blow to the head from a musket, and wounds from a sabre, pike and grapeshot.

Parker had the recaptured Hermione renamed HMS Retaliation, after which the Admiralty ordered her to be renamed HMS Retribution on 31 January 1800. The prize money was distributed making Hamilton a rich man, so much so that he declined a pension.

For his daring exploit, Hamilton was made a knight by letters patent, a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath (2 January 1815), and eventually became a baronet (20 October 1818). The Jamaica House of Assemblyawarded him a sword worth 300 guineas, and the City of London awarded him the Freedom of the City in a public dinner on 25 October 1800.

In 1847, the Admiralty awarded Hamilton a gold medal for the recapture of Hermione, and the Naval General Service Medal with the clasp, "Surprise with Hermione", to the seven surviving claimants from the action.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cutting_out_of_the_Hermione

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Surprise_(1796)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Hermione_(1782)