Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

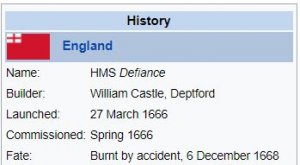

27 March 1666 – Launch of HMS Defiance, a 64-gun third rate ship of the line of the English Royal Navy,

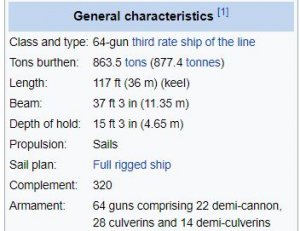

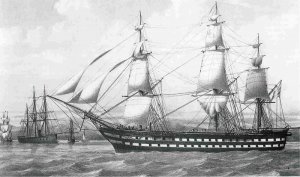

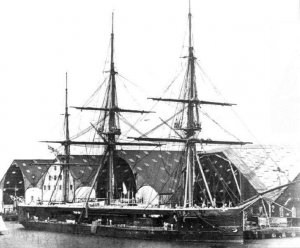

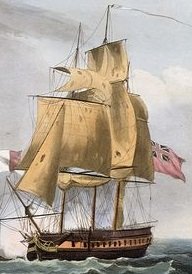

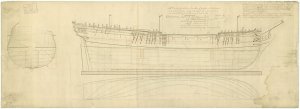

HMS Defiance was a 64-gun third rate ship of the line of the English Royal Navy, ordered on 26 October 1664 under the new construction programme of that year, and launched on 27 March 1666 at William Castle's private shipyard at Deptford in the presence of King Charles II.

She was commissioned under Sir Robert Holmes and took part in the Four Days Battle on 1 June 1666—4 June 1666. Following the battle, Holmes was briefly replaced by Captain William Flawes, but a month later command was taken by Rear-Admiral Sir John Kempthorne. In September 1667 Holmes, now Commander-in-Chief at Portsmouth, was back in command, but later that year he gave way to Sir John Harman in the same role. Defiance was accidentally destroyed by fire at Chatham on 6 December 1668.

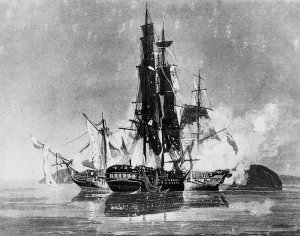

An incident during the second year of the Second Dutch War, 1665-67. It was fought in the southern North Sea between an English fleet of 56 ships under the command of the Duke of Albermarle and a larger Dutch fleet commanded by Lieutenant-Admiral Michiel de Ruyter. The action was fiercely contested, but eventually the English gained the weather position and comparative safety, although large numbers of casualties were incurred on both sides. This is a large and highly detailed painting of the action. In the immediate foreground, two English ships are shown in their last moments afloat. On the left is a partially dismasted and sinking two-decker with a blue ensign, in starboard-quarter view, and on her beam-ends to port. The royal crest on her stern is still visible and men can be seen clinging to the rigging, or in the water around the sinking vessel, awaiting rescue by some of the small boats nearby. The topmast of a vessel that has totally sunk is shown to the right of this ship. On the right in the foreground another two-decker, in port-broadside view, is burning. Men are swimming away from the vessel but several are shown clinging to the top of the mast. The focal point of the painting is the group of ships containing the two commanders-in-chief in the middle distance and left centre. The Duke of Albermarle, Admiral of the Red, in the 'Royal Charles', 80 guns, in starboard-bow view, is engaged with de Ruyter's flagship 'Zeven Provincien', 80 guns, port quarter view. She in her turn is engaging Rear-Admiral Robert Holmes's flagship the 'Defiance', 66 guns in starboard-quarter view, to the right. On the right-hand side of the painting, an English ship with a blue ensign, in starboard-quarter view, is surrendering and to her right the English 'Royal Prince', 85 guns, in starboard-quarter view, and another ship of her squadron following her are fighting it out with the Dutch Lieutenant-Admiral Cornelis Evertsen senior on the 'Walcheren', 68 guns, and Vice-Admiral Adrianne Banckert on the 'Tholen', 60 guns. In the background beyond the 'Royal Prince' and to the left Rear-Admiral John Harman in the 'Henry', 82 guns, in port-quarter view, is surrounded by three Dutch ships the right-hand one being Rear-Admiral Cornelis Evertsen junior's flagship. In the extreme right background is a melée of private ships with two English ones surrendered and one of these sailing out of the canvas and the action. In the extreme left middle distance is the 'Royal Prince', in action with two Dutch ships, and to the right of this and in the background Tromp's flagship, 'Hollandia', 86 guns, in starboard-quarter view. This is before he shifted his command and he is shown with the correct striped 'double prince' flags, unlike the other flag officers in his squadron, Sweers and van de Hulst. Despite the size of the painting and the number of ships depicted in the action, two-thirds of the picture consists of sky. The artist worked in Amsterdam, where he was burgomaster in 1642. He may have trained with the marine artist Claes Claesz Wou, and he is best known for panoramic battle scenes from the time of the Second Dutch War.

Samuel Pepys was a member of the Court Martial of the ship's gunner who was accused of causing the loss of the ship. In Pepys' diary entry for 25 March 1669, he writes that the ship was lost due to the "neglect" of the gunner "in trusting a girl to carry fire into his cabin".

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

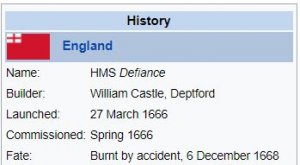

27 March 1666 – Launch of HMS Defiance, a 64-gun third rate ship of the line of the English Royal Navy,

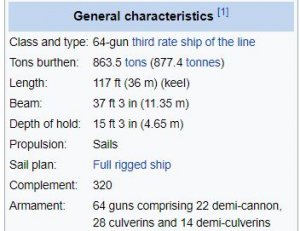

HMS Defiance was a 64-gun third rate ship of the line of the English Royal Navy, ordered on 26 October 1664 under the new construction programme of that year, and launched on 27 March 1666 at William Castle's private shipyard at Deptford in the presence of King Charles II.

She was commissioned under Sir Robert Holmes and took part in the Four Days Battle on 1 June 1666—4 June 1666. Following the battle, Holmes was briefly replaced by Captain William Flawes, but a month later command was taken by Rear-Admiral Sir John Kempthorne. In September 1667 Holmes, now Commander-in-Chief at Portsmouth, was back in command, but later that year he gave way to Sir John Harman in the same role. Defiance was accidentally destroyed by fire at Chatham on 6 December 1668.

An incident during the second year of the Second Dutch War, 1665-67. It was fought in the southern North Sea between an English fleet of 56 ships under the command of the Duke of Albermarle and a larger Dutch fleet commanded by Lieutenant-Admiral Michiel de Ruyter. The action was fiercely contested, but eventually the English gained the weather position and comparative safety, although large numbers of casualties were incurred on both sides. This is a large and highly detailed painting of the action. In the immediate foreground, two English ships are shown in their last moments afloat. On the left is a partially dismasted and sinking two-decker with a blue ensign, in starboard-quarter view, and on her beam-ends to port. The royal crest on her stern is still visible and men can be seen clinging to the rigging, or in the water around the sinking vessel, awaiting rescue by some of the small boats nearby. The topmast of a vessel that has totally sunk is shown to the right of this ship. On the right in the foreground another two-decker, in port-broadside view, is burning. Men are swimming away from the vessel but several are shown clinging to the top of the mast. The focal point of the painting is the group of ships containing the two commanders-in-chief in the middle distance and left centre. The Duke of Albermarle, Admiral of the Red, in the 'Royal Charles', 80 guns, in starboard-bow view, is engaged with de Ruyter's flagship 'Zeven Provincien', 80 guns, port quarter view. She in her turn is engaging Rear-Admiral Robert Holmes's flagship the 'Defiance', 66 guns in starboard-quarter view, to the right. On the right-hand side of the painting, an English ship with a blue ensign, in starboard-quarter view, is surrendering and to her right the English 'Royal Prince', 85 guns, in starboard-quarter view, and another ship of her squadron following her are fighting it out with the Dutch Lieutenant-Admiral Cornelis Evertsen senior on the 'Walcheren', 68 guns, and Vice-Admiral Adrianne Banckert on the 'Tholen', 60 guns. In the background beyond the 'Royal Prince' and to the left Rear-Admiral John Harman in the 'Henry', 82 guns, in port-quarter view, is surrounded by three Dutch ships the right-hand one being Rear-Admiral Cornelis Evertsen junior's flagship. In the extreme right background is a melée of private ships with two English ones surrendered and one of these sailing out of the canvas and the action. In the extreme left middle distance is the 'Royal Prince', in action with two Dutch ships, and to the right of this and in the background Tromp's flagship, 'Hollandia', 86 guns, in starboard-quarter view. This is before he shifted his command and he is shown with the correct striped 'double prince' flags, unlike the other flag officers in his squadron, Sweers and van de Hulst. Despite the size of the painting and the number of ships depicted in the action, two-thirds of the picture consists of sky. The artist worked in Amsterdam, where he was burgomaster in 1642. He may have trained with the marine artist Claes Claesz Wou, and he is best known for panoramic battle scenes from the time of the Second Dutch War.

Samuel Pepys was a member of the Court Martial of the ship's gunner who was accused of causing the loss of the ship. In Pepys' diary entry for 25 March 1669, he writes that the ship was lost due to the "neglect" of the gunner "in trusting a girl to carry fire into his cabin".

straaten

straaten

of the success reached London in August.

of the success reached London in August.