Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

27 April 1785 – Launch of HMS Victorious, a 74-gun third rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, launched at Blackwall Yard, London

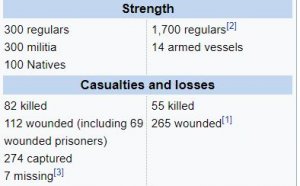

HMS Victorious was a 74-gun third rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, launched at Blackwall Yard, London on 27 April 1785. She was the first ship of the Royal Navy to bear the name.

Career

In April 1795, Victorious ran aground on the Shipwash Sand, in the North Sea off the coast of Suffolk and was dismasted.

During the month of February 1796, Victorious encountered and captured the French privateer brig Hasard, formerly the British pilot ship Cartier, which was returning to Île de France (Mauritius) with a 10-man crew after having captured the East Indiaman Triton.

She took part in the Action of 8 September 1796.

Victorious participated in the capture of the Dutch colony of Cape Town, in which an invasion had been caused due to fears of France's expansion across the world. Britain seized the strategic Cape Town and thus secured the nation its routes to the East. The rest of her career was spent in the warm climates of the East Indies, patrolling the vast waters in that region.

In 1801 Captain Pulteney Malcolm took command as Victorous served as flagship for Admiral Peter Rainier.

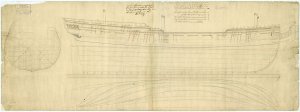

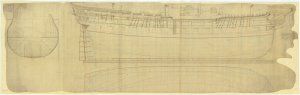

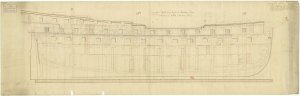

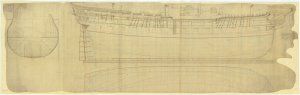

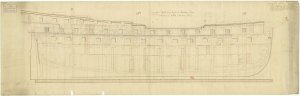

Plan showing the body plan, sheer lines, and longitudinal half-breadth for Thunderer (1783), Terrible (1785), Venerable (1784), Victorious (1785), Theseus (1786), Ramillies(1785), and Hannibal (1786), all 74-gun Third Rate, two-deckers. The plan also records alterations dated January 1813 for cutting down 74-gun Third Rates to Frigates, relating specifically to Majestic (1785), Resolution (1770), and Culloden (1783), all 74-gun Third Rate, two-deckers. Only the Majestic was cut down to a 58-gun Fourth Rate, as the other two were broken up in 1813.

Fate

On her homeward passage from the East Indies in 1803, Victorious proved exceedingly leaky. When she met with heavy weather in the North Atlantic, her crew had difficulty keeping her afloat till she reached the Tagus, where she was run ashore. Malcolm, with the officers and crew, returned to England in two vessels that he chartered at Lisbon. She was condemned and then broken up in August at Lisbon.

On 1 August Sir Andrew Mitchell arrived at Portsmouth, in company with Calpe, carrying Malcolm, his officers, and crew.[5] Sir Andrew Mitchell, R. Gilmore, master, was a 14-year old, 522-ton (bm) ship on the Cork-Lisbon trade.

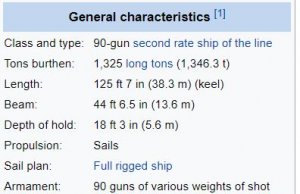

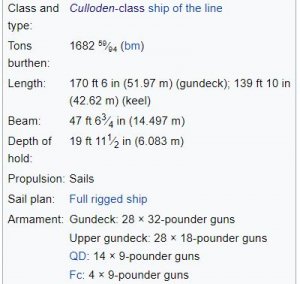

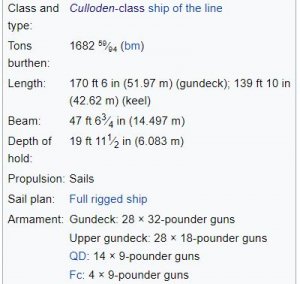

The Culloden-class ships of the line were a class of eight 74-gun third rates, designed for the Royal Navy by Sir Thomas Slade. The Cullodens were the last class of 74s which Slade designed before his death in 1771.

Ships

Builder: Deptford Dockyard

Ordered: 30 November 1769

Launched: 18 May 1776

Fate: Wrecked, 1781

Builder: Wells, Rotherhithe

Ordered: 23 August 1781

Launched: 13 November 1783

Fate: Broken up, 1814

Builder: Perry, Wells & Green, Blackwall Yard

Ordered: 9 August 1781

Launched: 19 April 1784

Fate: Wrecked, 1804

Builder: Wells, Rotherhithe

Ordered: 13 December 1781

Launched: 28 March 1785

Fate: Broken up, 1836

Builder: Perry, Blackwall Yard

Ordered: 28 December 1781

Launched: 27 April 1785

Fate: Broken up, 1803

Builder: Randall, Rotherhithe

Ordered: 19 June 1782

Launched: 12 July 1785

Fate: Broken up, 1850

Builder: Perry, Blackwall Yard

Ordered: 19 June 1782

Launched: 15 April 1786

Fate: Captured, 1801

Builder: Perry, Blackwall Yard

Ordered: 11 July 1780

Launched: 25 September 1786

Fate: Broken up, 1814

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Victorious_(1785)

en.wikipedia.org

https://collections.rmg.co.uk/colle...el-357740;browseBy=vessel;vesselFacetLetter=V

en.wikipedia.org

https://collections.rmg.co.uk/colle...el-357740;browseBy=vessel;vesselFacetLetter=V

27 April 1785 – Launch of HMS Victorious, a 74-gun third rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, launched at Blackwall Yard, London

HMS Victorious was a 74-gun third rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, launched at Blackwall Yard, London on 27 April 1785. She was the first ship of the Royal Navy to bear the name.

Career

In April 1795, Victorious ran aground on the Shipwash Sand, in the North Sea off the coast of Suffolk and was dismasted.

During the month of February 1796, Victorious encountered and captured the French privateer brig Hasard, formerly the British pilot ship Cartier, which was returning to Île de France (Mauritius) with a 10-man crew after having captured the East Indiaman Triton.

She took part in the Action of 8 September 1796.

Victorious participated in the capture of the Dutch colony of Cape Town, in which an invasion had been caused due to fears of France's expansion across the world. Britain seized the strategic Cape Town and thus secured the nation its routes to the East. The rest of her career was spent in the warm climates of the East Indies, patrolling the vast waters in that region.

In 1801 Captain Pulteney Malcolm took command as Victorous served as flagship for Admiral Peter Rainier.

Plan showing the body plan, sheer lines, and longitudinal half-breadth for Thunderer (1783), Terrible (1785), Venerable (1784), Victorious (1785), Theseus (1786), Ramillies(1785), and Hannibal (1786), all 74-gun Third Rate, two-deckers. The plan also records alterations dated January 1813 for cutting down 74-gun Third Rates to Frigates, relating specifically to Majestic (1785), Resolution (1770), and Culloden (1783), all 74-gun Third Rate, two-deckers. Only the Majestic was cut down to a 58-gun Fourth Rate, as the other two were broken up in 1813.

Fate

On her homeward passage from the East Indies in 1803, Victorious proved exceedingly leaky. When she met with heavy weather in the North Atlantic, her crew had difficulty keeping her afloat till she reached the Tagus, where she was run ashore. Malcolm, with the officers and crew, returned to England in two vessels that he chartered at Lisbon. She was condemned and then broken up in August at Lisbon.

On 1 August Sir Andrew Mitchell arrived at Portsmouth, in company with Calpe, carrying Malcolm, his officers, and crew.[5] Sir Andrew Mitchell, R. Gilmore, master, was a 14-year old, 522-ton (bm) ship on the Cork-Lisbon trade.

The Culloden-class ships of the line were a class of eight 74-gun third rates, designed for the Royal Navy by Sir Thomas Slade. The Cullodens were the last class of 74s which Slade designed before his death in 1771.

Ships

Builder: Deptford Dockyard

Ordered: 30 November 1769

Launched: 18 May 1776

Fate: Wrecked, 1781

Builder: Wells, Rotherhithe

Ordered: 23 August 1781

Launched: 13 November 1783

Fate: Broken up, 1814

Builder: Perry, Wells & Green, Blackwall Yard

Ordered: 9 August 1781

Launched: 19 April 1784

Fate: Wrecked, 1804

Builder: Wells, Rotherhithe

Ordered: 13 December 1781

Launched: 28 March 1785

Fate: Broken up, 1836

Builder: Perry, Blackwall Yard

Ordered: 28 December 1781

Launched: 27 April 1785

Fate: Broken up, 1803

Builder: Randall, Rotherhithe

Ordered: 19 June 1782

Launched: 12 July 1785

Fate: Broken up, 1850

Builder: Perry, Blackwall Yard

Ordered: 19 June 1782

Launched: 15 April 1786

Fate: Captured, 1801

Builder: Perry, Blackwall Yard

Ordered: 11 July 1780

Launched: 25 September 1786

Fate: Broken up, 1814

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Victorious_(1785)

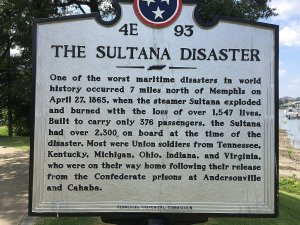

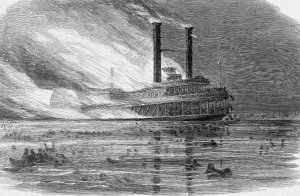

paper accounts indicate that the people of Memphis had sympathy for the victims despite the fact that they were an occupied city. The Chicago Opera Troupe, a minstrel group that had traveled upriver on the Sultana before getting off at Memphis, staged a benefit, while the crew of the gunboat Essex raised $1,000.

paper accounts indicate that the people of Memphis had sympathy for the victims despite the fact that they were an occupied city. The Chicago Opera Troupe, a minstrel group that had traveled upriver on the Sultana before getting off at Memphis, staged a benefit, while the crew of the gunboat Essex raised $1,000.