There is something fascinating in those pre-dreadnought battleships...the way they look, the way they operate and their fate...13 May 1906 – Launch of Ioann Zlatoust (Russian: Иоанн Златоуст), an Evstafi-class pre-dreadnought battleship of the Imperial Russian Navy's Black Sea Fleet.

-

Win a Free Custom Engraved Brass Coin!!!

As a way to introduce our brass coins to the community, we will raffle off a free coin during the month of August. Follow link ABOVE for instructions for entering.

-

PRE-ORDER SHIPS IN SCALE TODAY!

The beloved Ships in Scale Magazine is back and charting a new course for 2026!

Discover new skills, new techniques, and new inspirations in every issue.

NOTE THAT OUR FIRST ISSUE WILL BE JAN/FEB 2026

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Naval/Maritime History 27th of August - Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

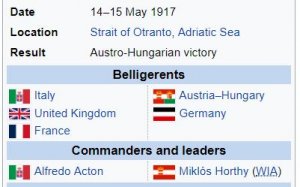

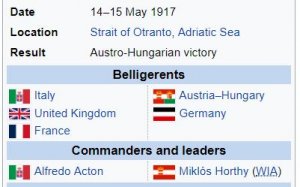

14 May 1917 - The 1917 Battle of the Strait of Otranto was the result of an Austro-Hungarian raid on the Otranto Barrage, an Allied naval blockade of the Strait of Otranto.

The battle took place on 14–15 May 1917, and was the largest surface action in the Adriatic Sea during World War I

The 1917 Battle of the Strait of Otranto was the result of an Austro-Hungarian raid on the Otranto Barrage, an Allied naval blockade of the Strait of Otranto. The battle took place on 14–15 May 1917, and was the largest surface action in the Adriatic Sea during World War I. The Otranto Barrage was a fixed barrier, composed of lightly armed drifters with anti-submarine nets coupled with minefields and supported by Allied naval patrols.

The Austro-Hungarian navy planned to raid the Otranto Barrage with a force of three light cruisers and two destroyers under the command of Commander (later Admiral) Miklós Horthy, in an attempt to break the barrier to allow U-boats freer access to the Mediterranean, and Allied shipping. An Allied force composed of ships from three navies responded to the raid and in the ensuing battle, heavily damaged the Austro-Hungarian cruiser SMS Novara. However, the rapid approach of the Austro-Hungarian relief force persuaded Rear Admiral Acton, the Allied commander, to retreat.

SMS Novara in action

Disposition of forces

Under the command of Horthy, three Austro-Hungarian cruisers (Novara, Saida, and Helgoland, modified to resemble large British destroyers) were ordered to attack the drifters on the night of 14 May and attempt to destroy as many as possible before daybreak. The destroyers Csepel and Balatonwere to mount a diversionary raid off the Albanian coast in order to confuse any Allied counter-attack. Two Austro-Hungarian U-boats—U-4 and U-27, along with the German U-boat UC-25—were to participate in the operation as well. A supporting force composed of the armored cruiser Sankt Georg, two destroyers, and four 250t-class torpedo boats was on standby if the raiders ran into trouble. The old pre-dreadnought battleship SMS Budapest and three more 250t-class torpedo boats were also available if necessary.

An Allied destroyer patrol was in the area on the night of 14 May, to the north of the Barrage. The Italian flotilla leader Mirabello was accompanied by the French destroyers Commandant Rivière, Bisson and Cimeterre. The Italian destroyer Borea was also in the area, escorting a small convoy to Valona. A support force was based in the port of Brindisi, consisting of the British cruisers Dartmouth and Bristol and several French and Italian destroyers.

Raid on the drifters

British drifters sailing from their base in the Adriatic to the Barrage

The Italian convoy escorted by Borea was attacked by the Austro-Hungarian destroyers Csepel and Balaton at approximately 03:24. The Austro-Hungarians sank Borea and a munitions ship, and a second was set on fire and abandoned.

The three cruisers were able to pass through the line of drifters, and at 03:30 began attacking the small barrage ships. The Austro-Hungarians frequently gave the drifter crews warning to abandon ship before opening fire. In some instances, the drifter crews chose to fight: Gowan Lee returned fire on the Austro-Hungarian ships. The ship was heavily damaged, but remained afloat; her captain—Joseph Watt—was later awarded the Victoria Cross for his actions during the battle.

There were 47 drifters in Barrage on the night of 14 May; the Austro-Hungarians managed to sink 14 drifters and damage four more. The lack of sufficient Allied escorts forced the withdrawal of the remaining blockading ships, although only for a short time.

Battle

By this time, the Allied naval forces in the area were aware of the raid, and were in a position to block the Austro-Hungarian retreat. Rear Admiral Alfredo Acton—the commanding officer of the Italian Scouting Division—ordered Mirabello's group southward at 04:35, while he embarked on the British light cruiser HMS Dartmouth. By 06:45, the cruisers Dartmouth and Bristol—along with the Italian destroyers Mosto, Pilo, Schiaffino, Acerbi, and Aquila—were sailing north in an attempt to cut off the Austro-Hungarian cruisers. The Italian light cruiser Marsala, the flotilla leader Racchia, and the destroyers Insidioso, Indomito, and Impavido were readying to sail in support as well.

The Mirabello group engaged the Austro-Hungarian cruisers at 07:00, but were heavily outgunned, and instead attempted to shadow the fleeing cruisers. At 07:45, Rear Admiral Acton's ships encountered the destroyers Csepel and Balaton. After 20 minutes, the Italian destroyers were able to close the distance to the Austro-Hungarian ships; the two groups engaged in a short artillery duel before a shot from Csepel struck Aquila and disabled the ship's boilers. By this time, the Austro-Hungarian destroyers were under the cover of the coastal batteries at Durazzo, and were able to make good their escape.

At 09:00, Bristol's lookouts spotted the smoke from the Austro-Hungarian cruisers to the south of her position. The Allied ships turned to engage the Austro-Hungarian ships; the British ships had a superiority both in numbers and in firepower; Dartmouth was armed with eight 6 in (150 mm) guns and Bristol had two 6 inch and ten 4 in (100 mm), compared to the nine 3.9 in (99 mm) guns on each of the Austro-Hungarian ships. Unfortunately for the Allies, their numerical superiority was quickly lost, as their destroyers were either occupied with mechanical problems, or protecting those destroyers suffering from breakdowns. The support forces of both sides—the Sankt Georg group for the Austro-Hungarians, and the Marsala group for the Allies—were quickly dispatched to the battle.

Italian FBA seaplanes from the seaplane carrier Europa shadowed the Austro-Hungarian cruisers and eventually dropped bombs on Helgoland, only scoring a near-miss that dislodged some rivets in her rudder.

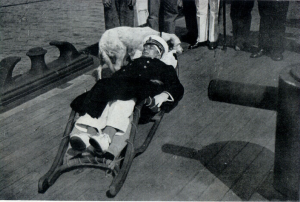

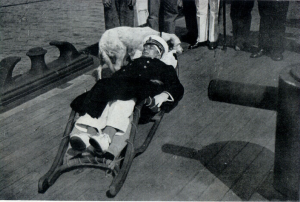

Horthy, seriously wounded, commanded the Austro-Hungarian fleet until falling unconscious.

Dartmouth—faster than Bristol—closed to effective engagement range with the Austro-Hungarian ships, and opened fire. A shell from Dartmouth struck Novara, at which point the Austro-Hungarian ships laid a smoke screen in order to close the distance. Dartmouth was struck several times, and by 11:00, Acton ordered the ship to reduce speed to allow Bristol to catch up. Novara was hit several more times, and her main feed pumps and starboard auxiliary steam pipe had been damaged, which caused the ship to begin losing speed. At 11:05, Acton turned away in an attempt to separate Saida from Novara and Helgoland. At this point, Sankt Georgwas approaching the scene, which prompted Acton to temporarily withdraw to consolidate his forces. This break in the action was enough time for the Austro-Hungarians to save the crippled Novara; Saida took the ship under tow while Helgoland covered them.

Unaware that Novara had been disabled, and fearing that his ships would be drawn too close to the Austrian naval base at Cattaro, Acton broke off the pursuit. The destroyer Acerbi misread the signal, and attempted to launch a torpedo attack, but was driven off by the combined fire of Novara, Saida, and Helgoland. At 12:05, Acton realized the dire situation Novara was in, but by this time, the Sankt Georg group was too close. The Sankt Georg group rendezvoused with Novara, Saida, and Helgoland, and Csepel and Balaton reached the scene as well. The entire group returned to Cattaro together.

At 13:30, the submarine UC-25 torpedoed Dartmouth, causing serious damage. The escorting destroyers forced UC-25 from the area, but Dartmouth had to be abandoned for a period of time, before it could be towed back to port. The French destroyer Boutefeu attempted to pursue the German submarine, but struck a mine laid by UC-25 that morning and sank rapidly.

Aftermath

Monument for "heroes of Otranto battle" on Prevlaka in today Croatia

As a result of the raid, it was decided by the British naval command that unless sufficient destroyers were available to protect the barrage, the drifters would have to be withdrawn at night. The drifters would only be operating for less than twelve hours a day, and would have to leave their positions by 15:00 every day. Despite the damage received by the Austro-Hungarian cruisers during the pursuit by Dartmouth and Bristol, the Austro-Hungarian forces inflicted more serious casualties on the Allied blockade. In addition to the sunk and damaged drifters, the cruiser Dartmouth was nearly sunk by the German submarine UC-25, the French destroyer Boutefeu was mined and sunk, and a munitions convoy to Valona was interdicted.

However, in a strategic sense, the battle had little impact on the war. The barrage was never particularly effective at preventing the U-boat operations of Germany and Austria-Hungary in the first place. The drifters could cover approximately .5 mi (0.80 km) apiece; of the 40 mi (64 km)-wide Strait, only slightly more than half was covered. The raid risked some of the most advanced units of the Austro-Hungarian fleet on an operation that offered minimal strategic returns.

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

14 May 1917 - The 1917 Battle of the Strait of Otranto was the result of an Austro-Hungarian raid on the Otranto Barrage, an Allied naval blockade of the Strait of Otranto.

The battle took place on 14–15 May 1917, and was the largest surface action in the Adriatic Sea during World War I

The 1917 Battle of the Strait of Otranto was the result of an Austro-Hungarian raid on the Otranto Barrage, an Allied naval blockade of the Strait of Otranto. The battle took place on 14–15 May 1917, and was the largest surface action in the Adriatic Sea during World War I. The Otranto Barrage was a fixed barrier, composed of lightly armed drifters with anti-submarine nets coupled with minefields and supported by Allied naval patrols.

The Austro-Hungarian navy planned to raid the Otranto Barrage with a force of three light cruisers and two destroyers under the command of Commander (later Admiral) Miklós Horthy, in an attempt to break the barrier to allow U-boats freer access to the Mediterranean, and Allied shipping. An Allied force composed of ships from three navies responded to the raid and in the ensuing battle, heavily damaged the Austro-Hungarian cruiser SMS Novara. However, the rapid approach of the Austro-Hungarian relief force persuaded Rear Admiral Acton, the Allied commander, to retreat.

SMS Novara in action

Disposition of forces

Under the command of Horthy, three Austro-Hungarian cruisers (Novara, Saida, and Helgoland, modified to resemble large British destroyers) were ordered to attack the drifters on the night of 14 May and attempt to destroy as many as possible before daybreak. The destroyers Csepel and Balatonwere to mount a diversionary raid off the Albanian coast in order to confuse any Allied counter-attack. Two Austro-Hungarian U-boats—U-4 and U-27, along with the German U-boat UC-25—were to participate in the operation as well. A supporting force composed of the armored cruiser Sankt Georg, two destroyers, and four 250t-class torpedo boats was on standby if the raiders ran into trouble. The old pre-dreadnought battleship SMS Budapest and three more 250t-class torpedo boats were also available if necessary.

An Allied destroyer patrol was in the area on the night of 14 May, to the north of the Barrage. The Italian flotilla leader Mirabello was accompanied by the French destroyers Commandant Rivière, Bisson and Cimeterre. The Italian destroyer Borea was also in the area, escorting a small convoy to Valona. A support force was based in the port of Brindisi, consisting of the British cruisers Dartmouth and Bristol and several French and Italian destroyers.

Raid on the drifters

British drifters sailing from their base in the Adriatic to the Barrage

The Italian convoy escorted by Borea was attacked by the Austro-Hungarian destroyers Csepel and Balaton at approximately 03:24. The Austro-Hungarians sank Borea and a munitions ship, and a second was set on fire and abandoned.

The three cruisers were able to pass through the line of drifters, and at 03:30 began attacking the small barrage ships. The Austro-Hungarians frequently gave the drifter crews warning to abandon ship before opening fire. In some instances, the drifter crews chose to fight: Gowan Lee returned fire on the Austro-Hungarian ships. The ship was heavily damaged, but remained afloat; her captain—Joseph Watt—was later awarded the Victoria Cross for his actions during the battle.

There were 47 drifters in Barrage on the night of 14 May; the Austro-Hungarians managed to sink 14 drifters and damage four more. The lack of sufficient Allied escorts forced the withdrawal of the remaining blockading ships, although only for a short time.

Battle

By this time, the Allied naval forces in the area were aware of the raid, and were in a position to block the Austro-Hungarian retreat. Rear Admiral Alfredo Acton—the commanding officer of the Italian Scouting Division—ordered Mirabello's group southward at 04:35, while he embarked on the British light cruiser HMS Dartmouth. By 06:45, the cruisers Dartmouth and Bristol—along with the Italian destroyers Mosto, Pilo, Schiaffino, Acerbi, and Aquila—were sailing north in an attempt to cut off the Austro-Hungarian cruisers. The Italian light cruiser Marsala, the flotilla leader Racchia, and the destroyers Insidioso, Indomito, and Impavido were readying to sail in support as well.

The Mirabello group engaged the Austro-Hungarian cruisers at 07:00, but were heavily outgunned, and instead attempted to shadow the fleeing cruisers. At 07:45, Rear Admiral Acton's ships encountered the destroyers Csepel and Balaton. After 20 minutes, the Italian destroyers were able to close the distance to the Austro-Hungarian ships; the two groups engaged in a short artillery duel before a shot from Csepel struck Aquila and disabled the ship's boilers. By this time, the Austro-Hungarian destroyers were under the cover of the coastal batteries at Durazzo, and were able to make good their escape.

At 09:00, Bristol's lookouts spotted the smoke from the Austro-Hungarian cruisers to the south of her position. The Allied ships turned to engage the Austro-Hungarian ships; the British ships had a superiority both in numbers and in firepower; Dartmouth was armed with eight 6 in (150 mm) guns and Bristol had two 6 inch and ten 4 in (100 mm), compared to the nine 3.9 in (99 mm) guns on each of the Austro-Hungarian ships. Unfortunately for the Allies, their numerical superiority was quickly lost, as their destroyers were either occupied with mechanical problems, or protecting those destroyers suffering from breakdowns. The support forces of both sides—the Sankt Georg group for the Austro-Hungarians, and the Marsala group for the Allies—were quickly dispatched to the battle.

Italian FBA seaplanes from the seaplane carrier Europa shadowed the Austro-Hungarian cruisers and eventually dropped bombs on Helgoland, only scoring a near-miss that dislodged some rivets in her rudder.

Horthy, seriously wounded, commanded the Austro-Hungarian fleet until falling unconscious.

Dartmouth—faster than Bristol—closed to effective engagement range with the Austro-Hungarian ships, and opened fire. A shell from Dartmouth struck Novara, at which point the Austro-Hungarian ships laid a smoke screen in order to close the distance. Dartmouth was struck several times, and by 11:00, Acton ordered the ship to reduce speed to allow Bristol to catch up. Novara was hit several more times, and her main feed pumps and starboard auxiliary steam pipe had been damaged, which caused the ship to begin losing speed. At 11:05, Acton turned away in an attempt to separate Saida from Novara and Helgoland. At this point, Sankt Georgwas approaching the scene, which prompted Acton to temporarily withdraw to consolidate his forces. This break in the action was enough time for the Austro-Hungarians to save the crippled Novara; Saida took the ship under tow while Helgoland covered them.

Unaware that Novara had been disabled, and fearing that his ships would be drawn too close to the Austrian naval base at Cattaro, Acton broke off the pursuit. The destroyer Acerbi misread the signal, and attempted to launch a torpedo attack, but was driven off by the combined fire of Novara, Saida, and Helgoland. At 12:05, Acton realized the dire situation Novara was in, but by this time, the Sankt Georg group was too close. The Sankt Georg group rendezvoused with Novara, Saida, and Helgoland, and Csepel and Balaton reached the scene as well. The entire group returned to Cattaro together.

At 13:30, the submarine UC-25 torpedoed Dartmouth, causing serious damage. The escorting destroyers forced UC-25 from the area, but Dartmouth had to be abandoned for a period of time, before it could be towed back to port. The French destroyer Boutefeu attempted to pursue the German submarine, but struck a mine laid by UC-25 that morning and sank rapidly.

Aftermath

Monument for "heroes of Otranto battle" on Prevlaka in today Croatia

As a result of the raid, it was decided by the British naval command that unless sufficient destroyers were available to protect the barrage, the drifters would have to be withdrawn at night. The drifters would only be operating for less than twelve hours a day, and would have to leave their positions by 15:00 every day. Despite the damage received by the Austro-Hungarian cruisers during the pursuit by Dartmouth and Bristol, the Austro-Hungarian forces inflicted more serious casualties on the Allied blockade. In addition to the sunk and damaged drifters, the cruiser Dartmouth was nearly sunk by the German submarine UC-25, the French destroyer Boutefeu was mined and sunk, and a munitions convoy to Valona was interdicted.

However, in a strategic sense, the battle had little impact on the war. The barrage was never particularly effective at preventing the U-boat operations of Germany and Austria-Hungary in the first place. The drifters could cover approximately .5 mi (0.80 km) apiece; of the 40 mi (64 km)-wide Strait, only slightly more than half was covered. The raid risked some of the most advanced units of the Austro-Hungarian fleet on an operation that offered minimal strategic returns.

Battle of the Strait of Otranto (1917) - Wikipedia

Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

14 May 1918 - 1918 - HMS Phoenix, an Acheron-class destroyer of the British Royal Navy, was the only British warship ever to be sunk by the Austro-Hungarian Navy.

HMS Phoenix was an Acheron-class destroyer of the British Royal Navy. She is named for the mythical bird, and was the fifteenth ship of the Royal Navy to bear the name. She was the only British warship ever to be sunk by the Austro-Hungarian Navy

Design

The Acheron-class (redesignated the I-class in October 1913) was an improved version of the Acorn-class destroyer which had been built for the Royal Navy under the 1909–1910 shipbuilding programme. Fourteen destroyers were ordered for the Royal Navy to the standard Admiralty design, with six more as 'builder's specials', to the design of specialist destroyer shipyards, later followed by three more high-speed specials and six for Australia.

The Acherons were 246 ft (74.98 m) long overall, with a beam of 25 feet 8 inches (7.82 m) and a draught of 9 feet (2.7 m). Displacement was about 773 long tons (785 t) legend and 990 long tons (1,010 t)} deep load. Three Yarrow water-tube boilers fed steam to Parsons steam turbines which drove three shafts. The machinery was rated at 13,500 shaft horsepower (10,100 kW), giving a speed of 27 knots (31 mph; 50 km/h). Two funnels were fitted.

The ships were armed with two 4-inch (102 mm) BL Mk VIII on the centreline and two 12-pounder 12 cwt[a] guns on the ship's beam. Two single 21-inch (533 mm) torpedo tubes were fitted. The ships had a complement of 72 men.

Phoenix was laid down at Vickers' Barrow-in-Furness shipyard on 4 January 1911, was launched on 9 October 1911 and was completed in May 1912.

Career

At the beginning of the First World War, Phoenix was part of the First Destroyer Flotilla operating in the North Sea. She and her sisters were attached to the Grand Fleet as soon as the war started.

Action on 16 August 1914

On 16 August 1914, within days of the outbreak of war, the First Destroyer Flotilla engaged an enemy cruiser off the mouth of the Elbe, which is reported with great verve by an author writing under the pseudonym "Clinker Knocker" in 1938:

The Battle of Heligoland Bight

She was present with First Destroyer Flotilla on 28 August 1914 at the Battle of Heligoland Bight, led by the light cruiser Fearless.[9] Phoenix suffered one man wounded during the action

The Battle of Dogger Bank

On 24 January 1915 Phoenix took part in the Battle of Dogger Bank, and her crew shared in the Prize Money for the German armoured cruiser Blücher.

The Battle of Jutland

Phoenix was not present with her flotilla at the Battle of Jutland on 31 May 1916.

HMAT Ballarat

Phoenix was escorting the Australian troopship Ballarat when she was attacked by a German submarine on Anzac Day (25 April) 1917 in the English Channel. Although efforts were made to tow Ballarat to shallow water, she sank off The Lizard the following morning. No lives were lost of the 1,752 souls on board, a striking testament to the calmness and discipline of the troops.

Mediterranean Service

In September 1917, Phoenix transferred to the Fifth Destroyer Flotilla which was operating in the Mediterranean. This posting was to be her last.[13]

HMS Phoenix lists to port after being torpedoed, viewed from HMAS Warrego

Loss

At 9:18 on 14 May 1918, while patrolling the Otranto Barrage, the Phoenix was torpedoed amidships by the Austro-Hungarian submarine SM U-27, HMAS Warrego made an unsuccessful attempt to tow her to Valona (now Vlorë in Albania), but she sank within sight of the port at 13:10. The crew had been taken off before she capsized, and there were only two fatalities; a Leading Stoker and an Engine Room Artificer.

SM U-27 or U-XXVII was the lead boat of the U-27 class of U-boats or submarines for the Austro-Hungarian Navy. U-27 was built by the Austrian firm of Cantiere Navale Triestino (CNT) at the Pola Navy Yard and launched on 19 October 1916. She was commissioned on 24 February 1917.

She had a single hull and was just over 121 feet (37 m) in length. She displaced nearly 265 metric tons (261 long tons) when surfaced and over 300 metric tons (295 long tons) when submerged. Her two diesel engines moved her at up to 9 knots (17 km/h) on the surface, while her twin electric motorspropelled her at up to 7.5 knots (13.9 km/h) while underwater. She was armed with two bow torpedo tubes and could carry a load of up to four torpedoes. She was also equipped with a 75 mm (3.0 in) deck gun and a machine gun.

During her service career, U-27 sank the British destroyer Phoenix, damaged the Japanese destroyer Sakaki, and sank or captured 34 other ships totaling 14,386 GRT. U-27 was surrendered at Pola at war's end and handed over to Italy as a war reparation in 1919. She was broken up the following year. Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships, 1906–1921 calls U-27 Austria-Hungary's "most successful submarine".

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Phoenix_(1911)

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

14 May 1918 - 1918 - HMS Phoenix, an Acheron-class destroyer of the British Royal Navy, was the only British warship ever to be sunk by the Austro-Hungarian Navy.

HMS Phoenix was an Acheron-class destroyer of the British Royal Navy. She is named for the mythical bird, and was the fifteenth ship of the Royal Navy to bear the name. She was the only British warship ever to be sunk by the Austro-Hungarian Navy

Design

The Acheron-class (redesignated the I-class in October 1913) was an improved version of the Acorn-class destroyer which had been built for the Royal Navy under the 1909–1910 shipbuilding programme. Fourteen destroyers were ordered for the Royal Navy to the standard Admiralty design, with six more as 'builder's specials', to the design of specialist destroyer shipyards, later followed by three more high-speed specials and six for Australia.

The Acherons were 246 ft (74.98 m) long overall, with a beam of 25 feet 8 inches (7.82 m) and a draught of 9 feet (2.7 m). Displacement was about 773 long tons (785 t) legend and 990 long tons (1,010 t)} deep load. Three Yarrow water-tube boilers fed steam to Parsons steam turbines which drove three shafts. The machinery was rated at 13,500 shaft horsepower (10,100 kW), giving a speed of 27 knots (31 mph; 50 km/h). Two funnels were fitted.

The ships were armed with two 4-inch (102 mm) BL Mk VIII on the centreline and two 12-pounder 12 cwt[a] guns on the ship's beam. Two single 21-inch (533 mm) torpedo tubes were fitted. The ships had a complement of 72 men.

Phoenix was laid down at Vickers' Barrow-in-Furness shipyard on 4 January 1911, was launched on 9 October 1911 and was completed in May 1912.

Career

At the beginning of the First World War, Phoenix was part of the First Destroyer Flotilla operating in the North Sea. She and her sisters were attached to the Grand Fleet as soon as the war started.

Action on 16 August 1914

On 16 August 1914, within days of the outbreak of war, the First Destroyer Flotilla engaged an enemy cruiser off the mouth of the Elbe, which is reported with great verve by an author writing under the pseudonym "Clinker Knocker" in 1938:

| “ | On Aug 16th we had our first brush with the enemy, and our flotilla received a sample of German gunnery which our own gunners acknowledged was excellent. We were on our usual Dutch coast patrol, known as the 'broad fourteens' and were somewhere off the mouth of the river Elbe off the German coast. At daybreak we chased a German collier and made contact with a powerful armoured cruiser, which opened fire on us with 8.2 inch guns. Our heaviest gun was four-inch, so the enemy easily outranged us, and straddled us with her accurate salvo firing. The Goshawk and Phoenix were disabled, and shells were ricochetting over us. Fearless led us in a determined attack to close with torpedos, but the large German Cruiser foiled our intentions by running for home, and we did not blame her. We were very disappointed, however at not being able to equalise matters with the third flotilla, but the Yorch or Roon or whichever ship it may have been was too near home for us to follow, and we left the vicinity after the Goshawk and Phoenix had patched up their wounds. | ” |

| — Aye, Aye, Sir, a saga of the lower deck by Clinker Knocke |

The Battle of Heligoland Bight

She was present with First Destroyer Flotilla on 28 August 1914 at the Battle of Heligoland Bight, led by the light cruiser Fearless.[9] Phoenix suffered one man wounded during the action

The Battle of Dogger Bank

On 24 January 1915 Phoenix took part in the Battle of Dogger Bank, and her crew shared in the Prize Money for the German armoured cruiser Blücher.

The Battle of Jutland

Phoenix was not present with her flotilla at the Battle of Jutland on 31 May 1916.

HMAT Ballarat

Phoenix was escorting the Australian troopship Ballarat when she was attacked by a German submarine on Anzac Day (25 April) 1917 in the English Channel. Although efforts were made to tow Ballarat to shallow water, she sank off The Lizard the following morning. No lives were lost of the 1,752 souls on board, a striking testament to the calmness and discipline of the troops.

Mediterranean Service

In September 1917, Phoenix transferred to the Fifth Destroyer Flotilla which was operating in the Mediterranean. This posting was to be her last.[13]

HMS Phoenix lists to port after being torpedoed, viewed from HMAS Warrego

Loss

At 9:18 on 14 May 1918, while patrolling the Otranto Barrage, the Phoenix was torpedoed amidships by the Austro-Hungarian submarine SM U-27, HMAS Warrego made an unsuccessful attempt to tow her to Valona (now Vlorë in Albania), but she sank within sight of the port at 13:10. The crew had been taken off before she capsized, and there were only two fatalities; a Leading Stoker and an Engine Room Artificer.

SM U-27 or U-XXVII was the lead boat of the U-27 class of U-boats or submarines for the Austro-Hungarian Navy. U-27 was built by the Austrian firm of Cantiere Navale Triestino (CNT) at the Pola Navy Yard and launched on 19 October 1916. She was commissioned on 24 February 1917.

She had a single hull and was just over 121 feet (37 m) in length. She displaced nearly 265 metric tons (261 long tons) when surfaced and over 300 metric tons (295 long tons) when submerged. Her two diesel engines moved her at up to 9 knots (17 km/h) on the surface, while her twin electric motorspropelled her at up to 7.5 knots (13.9 km/h) while underwater. She was armed with two bow torpedo tubes and could carry a load of up to four torpedoes. She was also equipped with a 75 mm (3.0 in) deck gun and a machine gun.

During her service career, U-27 sank the British destroyer Phoenix, damaged the Japanese destroyer Sakaki, and sank or captured 34 other ships totaling 14,386 GRT. U-27 was surrendered at Pola at war's end and handed over to Italy as a war reparation in 1919. She was broken up the following year. Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships, 1906–1921 calls U-27 Austria-Hungary's "most successful submarine".

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Phoenix_(1911)

SM U-27 (Austria-Hungary) - Wikipedia

Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

14 May 1943 – World War II: A Japanese submarine sinks AHS Centaur off the coast of Queensland.

Australian Hospital Ship (AHS) Centaur was a hospital ship which was attacked and sunk by a Japanese submarine off the coast of Queensland, Australia, on 14 May 1943. Of the 332 medical personnel and civilian crew aboard, 268 died, including 63 of the 65 army personnel.

The Scottish-built vessel was launched in 1924 as a combination passenger liner and refrigerated cargo ship and operated a trade route between Western Australia and Singapore via the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), carrying passengers, cargo, and livestock. At the start of World War II, Centaur (like all British Merchant Navy vessels) was placed under British Admiralty control, but after being fitted with defensive equipment, was allowed to continue normal operations. In November 1941, the ship rescued German survivors of the engagement between Kormoran and HMAS Sydney. Centaur was relocated to Australia's east coast in October 1942, and used to transport materiel to New Guinea.

In January 1943, Centaur was handed over to the Australian military for conversion into a hospital ship, as the ship's small size made her suitable for operating in Maritime Southeast Asia. The refit (including installation of medical facilities and repainting with Red Cross markings) was completed in March, and the ship undertook a trial voyage: transporting wounded from Townsville to Brisbane, then from Port Moresby to Brisbane. After replenishing in Sydney, Centaur embarked the 2/12th Field Ambulance for transport to New Guinea, and sailed on 12 May. Before dawn on 14 May 1943, during her second voyage, Centaur was torpedoed and sunk by a Japanese submarine off North Stradbroke Island, Queensland. The majority of the 332 aboard died in the attack; the 64 survivors were discovered 36 hours later. The incident resulted in public outrage as attacking a hospital ship is considered a war crime under the 1907 Hague Convention. Protests were made by the Australian and British governments to Japan and efforts were made to discover the people responsible so they could be tried at a war crimes tribunal. In the 1970s the probable identity of the attacking submarine, I-177, became public.

The reason for the attack is unknown, with theories that Centaur was in breach of the international conventions that should have protected her, that I-177's commander was unaware that Centaur was a hospital ship, or that the submarine commander knowingly attacked a protected vessel. The wreck of Centaur was found on 20 December 2009; a claimed discovery in 1995 had been proven to be a different shipwreck.

AHS Centaur following her conversion to a hospital ship. The Red Cross designation "47" can be seen on the bow.

Sinking

At approximately 4:10 am on 14 May 1943, while on her second run from Sydney to Port Moresby, Centaur was torpedoed by an unsighted submarine. The torpedo struck the portside oil fuel tank approximately 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) below the waterline, creating a hole 8 to 10 metres (26 to 33 ft) across, igniting the fuel, and setting the ship on fire from the bridge aft. Many of those on board were immediately killed by concussion or perished in the inferno. Centaur quickly took on water through the impact site, rolled to port, then sank bow-first, submerging completely in less than three minutes. The rapid sinking prevented the deployment of lifeboats, although two broke off from Centaur as she sank, along with several damaged liferafts.

According to the position extrapolated by Second Officer Gordon Rippon from the 4:00 am dead reckoning position, Centaur was attacked approximately 24 nautical miles (44 km; 28 mi) east-northeast of Point Lookout, North Stradbroke Island, Queensland. Doubts were initially cast on the accuracy of both the calculated point of sinking and the dead reckoning position, but the 2009 discovery of the wreck found both to be correct, with Centaur located within 1 nautical mile (1.9 km; 1.2 mi) of Rippon's coordinates.

The survivors spent 36 hours in the water, using barrels, wreckage, and the two damaged lifeboats for flotation. During this time, they drifted approximately 19.6 nautical miles (36.3 km; 22.6 mi) north east of Centaur's calculated point of sinking and spread out over an area of 2 nautical miles (3.7 km; 2.3 mi). The survivors saw at least four ships and several aircraft, but could not attract their attention.

At the time of rescue, the survivors were in two large and three small groups, with several more floating alone. Amongst those rescued were Sister Ellen Savage, the only surviving nurse from 12 aboard; Leslie Outridge, the only surviving doctor from 18 aboard; Gordon Rippon, second officer and most senior surviving crew member; and Richard Salt, the Torres Strait ship pilot. In 1944, Ellen Savage was presented with the George Medal for providing medical care, boosting morale, and displaying courage during the wait for rescue.

Rescue

Sister Ellen Savage was the sole survivor of the 12 female nurses on board Centaur.

On the morning of 15 May 1943, the American destroyer USS Mugford departed Brisbane to escort the 11,063 ton New Zealand freighter Sussex on the first stage of the latter's trans-Tasman voyage. At 2:00 pm, a lookout aboard Mugford reported an object on the horizon. Around the same time, a Royal Australian Air Force Avro Ansonof No. 71 Squadron, flying ahead on anti-submarine watch, dived towards the object. The aircraft returned to the two ships and signalled that there were shipwreck survivors in the water requiring rescue. Mugford's commanding officer ordered Sussex to continue alone as Mugford collected the survivors. Marksmen were positioned around the ship to shoot sharks, and sailors stood ready to dive in and assist the wounded. Mugford's medics inspected each person as they came aboard and provided necessary medical care. The American crew learned from the first group of survivors that they were from the hospital ship Centaur.

At 2:14 pm, Mugford made contact with the Naval Officer-in-Charge in Brisbane, and announced that the ship was recovering survivors from Centaur at 27°03′S 154°12′E, the first that anyone in Australia had knowledge of the attack on the hospital ship. The rescue of the 64 survivors took an hour and twenty minutes, although Mugford remained in the area until dark, searching an area of approximately 7 by 14 nautical miles (13 by 26 km; 8 by 16 mi) for more survivors. After darkness fell, Mugford returned to Brisbane, arriving shortly before midnight. Further searches of the waters off North Stradbroke Island were made by USS Helm during the night of 15 May until 6:00 pm on 16 May, and by HMAS Lithgow and four motor torpedo boats from 16 to 21 May, with neither search finding more survivors.

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

14 May 1943 – World War II: A Japanese submarine sinks AHS Centaur off the coast of Queensland.

Australian Hospital Ship (AHS) Centaur was a hospital ship which was attacked and sunk by a Japanese submarine off the coast of Queensland, Australia, on 14 May 1943. Of the 332 medical personnel and civilian crew aboard, 268 died, including 63 of the 65 army personnel.

The Scottish-built vessel was launched in 1924 as a combination passenger liner and refrigerated cargo ship and operated a trade route between Western Australia and Singapore via the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), carrying passengers, cargo, and livestock. At the start of World War II, Centaur (like all British Merchant Navy vessels) was placed under British Admiralty control, but after being fitted with defensive equipment, was allowed to continue normal operations. In November 1941, the ship rescued German survivors of the engagement between Kormoran and HMAS Sydney. Centaur was relocated to Australia's east coast in October 1942, and used to transport materiel to New Guinea.

In January 1943, Centaur was handed over to the Australian military for conversion into a hospital ship, as the ship's small size made her suitable for operating in Maritime Southeast Asia. The refit (including installation of medical facilities and repainting with Red Cross markings) was completed in March, and the ship undertook a trial voyage: transporting wounded from Townsville to Brisbane, then from Port Moresby to Brisbane. After replenishing in Sydney, Centaur embarked the 2/12th Field Ambulance for transport to New Guinea, and sailed on 12 May. Before dawn on 14 May 1943, during her second voyage, Centaur was torpedoed and sunk by a Japanese submarine off North Stradbroke Island, Queensland. The majority of the 332 aboard died in the attack; the 64 survivors were discovered 36 hours later. The incident resulted in public outrage as attacking a hospital ship is considered a war crime under the 1907 Hague Convention. Protests were made by the Australian and British governments to Japan and efforts were made to discover the people responsible so they could be tried at a war crimes tribunal. In the 1970s the probable identity of the attacking submarine, I-177, became public.

The reason for the attack is unknown, with theories that Centaur was in breach of the international conventions that should have protected her, that I-177's commander was unaware that Centaur was a hospital ship, or that the submarine commander knowingly attacked a protected vessel. The wreck of Centaur was found on 20 December 2009; a claimed discovery in 1995 had been proven to be a different shipwreck.

AHS Centaur following her conversion to a hospital ship. The Red Cross designation "47" can be seen on the bow.

Sinking

At approximately 4:10 am on 14 May 1943, while on her second run from Sydney to Port Moresby, Centaur was torpedoed by an unsighted submarine. The torpedo struck the portside oil fuel tank approximately 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) below the waterline, creating a hole 8 to 10 metres (26 to 33 ft) across, igniting the fuel, and setting the ship on fire from the bridge aft. Many of those on board were immediately killed by concussion or perished in the inferno. Centaur quickly took on water through the impact site, rolled to port, then sank bow-first, submerging completely in less than three minutes. The rapid sinking prevented the deployment of lifeboats, although two broke off from Centaur as she sank, along with several damaged liferafts.

According to the position extrapolated by Second Officer Gordon Rippon from the 4:00 am dead reckoning position, Centaur was attacked approximately 24 nautical miles (44 km; 28 mi) east-northeast of Point Lookout, North Stradbroke Island, Queensland. Doubts were initially cast on the accuracy of both the calculated point of sinking and the dead reckoning position, but the 2009 discovery of the wreck found both to be correct, with Centaur located within 1 nautical mile (1.9 km; 1.2 mi) of Rippon's coordinates.

The survivors spent 36 hours in the water, using barrels, wreckage, and the two damaged lifeboats for flotation. During this time, they drifted approximately 19.6 nautical miles (36.3 km; 22.6 mi) north east of Centaur's calculated point of sinking and spread out over an area of 2 nautical miles (3.7 km; 2.3 mi). The survivors saw at least four ships and several aircraft, but could not attract their attention.

At the time of rescue, the survivors were in two large and three small groups, with several more floating alone. Amongst those rescued were Sister Ellen Savage, the only surviving nurse from 12 aboard; Leslie Outridge, the only surviving doctor from 18 aboard; Gordon Rippon, second officer and most senior surviving crew member; and Richard Salt, the Torres Strait ship pilot. In 1944, Ellen Savage was presented with the George Medal for providing medical care, boosting morale, and displaying courage during the wait for rescue.

Rescue

Sister Ellen Savage was the sole survivor of the 12 female nurses on board Centaur.

On the morning of 15 May 1943, the American destroyer USS Mugford departed Brisbane to escort the 11,063 ton New Zealand freighter Sussex on the first stage of the latter's trans-Tasman voyage. At 2:00 pm, a lookout aboard Mugford reported an object on the horizon. Around the same time, a Royal Australian Air Force Avro Ansonof No. 71 Squadron, flying ahead on anti-submarine watch, dived towards the object. The aircraft returned to the two ships and signalled that there were shipwreck survivors in the water requiring rescue. Mugford's commanding officer ordered Sussex to continue alone as Mugford collected the survivors. Marksmen were positioned around the ship to shoot sharks, and sailors stood ready to dive in and assist the wounded. Mugford's medics inspected each person as they came aboard and provided necessary medical care. The American crew learned from the first group of survivors that they were from the hospital ship Centaur.

At 2:14 pm, Mugford made contact with the Naval Officer-in-Charge in Brisbane, and announced that the ship was recovering survivors from Centaur at 27°03′S 154°12′E, the first that anyone in Australia had knowledge of the attack on the hospital ship. The rescue of the 64 survivors took an hour and twenty minutes, although Mugford remained in the area until dark, searching an area of approximately 7 by 14 nautical miles (13 by 26 km; 8 by 16 mi) for more survivors. After darkness fell, Mugford returned to Brisbane, arriving shortly before midnight. Further searches of the waters off North Stradbroke Island were made by USS Helm during the night of 15 May until 6:00 pm on 16 May, and by HMAS Lithgow and four motor torpedo boats from 16 to 21 May, with neither search finding more survivors.

AHS Centaur - Wikipedia

Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

Other Events on 14 May

1695 - Launch of french Fougueux 50 guns (designed and built by Blaise Pangalo, launched 14 May 1695 at Brest) – captured by the English in 1696, sank 1696

1717 - May 14 or 15 - Danish attack on Göteborg is defeated

1757 HMS Antelope (54), Cptn. Alexander Arthur Hood, drove ashore and wrecked Aquilon (50) in Audierne Bay.

HMS Antelope was a 50-gun fourth rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, launched at Rotherhithe on 13 March 1703. She was rebuilt once during her career, and served in the Seven Years' War and the American Revolutionary War.

Orders were issued on 9 January 1738 for Antelope to be taken to pieces and rebuilt according to the 1733 proposals of the 1719 Establishment at Woolwich, from where she was relaunched on 27 January 1741.

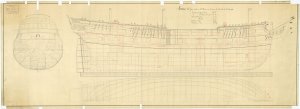

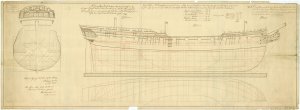

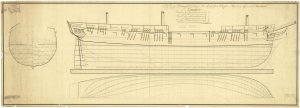

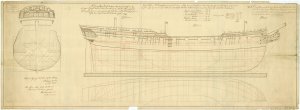

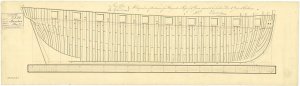

Scale: 1:48. Plan showing the body plan from midships to bow, body plan from midships to stern with stern board decoration, sheer lines with some inboard detail and figurehead, and longitudinal half-breadth with some lower deck detail for Antelope (1703), a 50-gun Fourth Rate two-decker. This may be the ship as she was when in Plymouth Dockyard in 1713. An attached letter (not scanned) lays out the dimensions of the ship, as taken at Plymouth on 7 March 1713

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

1757 - Aquilon 42, later 48 guns (launched 16 March 1741 at Toulon, designed and built by Jean-Armand Levasseur) – wrecked 14 May 1757.

1776 – Launch of HMS Romulus, a Roebuck-class ship was a class of twenty 44-gun sailing two-decker warships of the Royal Navy.

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

1778 – Launch of HMS Janus was a 44-gun Roebuck-class fifth rate of the Royal Navy.

HMS Janus was a 44-gun Roebuck-class fifth rate of the Royal Navy.

From May 1780 she was under the command of Captain Horatio Nelson, though he was superseded by September that year.

In 1793 she was under the command of Captain Sandford Tatham

Loss

HMS Dromedary was wrecked on the Parasol Rocks, Trinidad on 10 August 1800. Her entire complement survived.

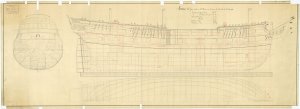

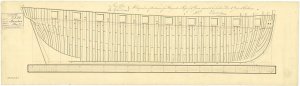

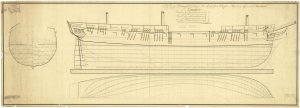

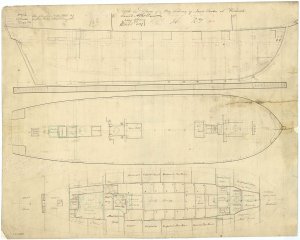

Scale: 1:48. Plan showing the body plan with stern board outline, sheer lines with inboard detail, and longitudinal half-breadth for Janus (1778), a 44-gun Fifth Rate, two-decker, as built at Limehouse by Mr Batson. The plan was possibly draughted at Deptford Dockyard as Janus was completed there between May and August 1778

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Janus_(1778)

1781 HMS Nonsuch (64), Cptn. Sir James Wallace, engaged Actif (74).

On 14 May 1781, on the homeward voyage, while scouting ahead, Nonsuch chased and brought to action the French 74-gun Actif, hoping to detain her until some others of the fleet came up. However, Actif was able to repulse Nonsuch, causing her to suffer 26 men killed and 64 wounded, and continued on to Brest.

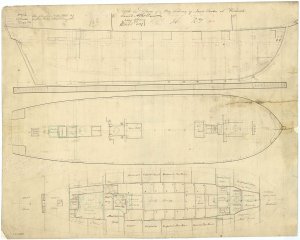

Scale: 1:48. Plan showing the body plan, sheer lines, and longitudinal half-breadth for Ruby (1776) and Nonsuch (1774), and later for Vigilant (1774), Eagle (1774), and America (1777), all 64-gun Third Rate, two-deckers. Signed by John Williams [Surveyor of the Navy, 1765-1784]

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

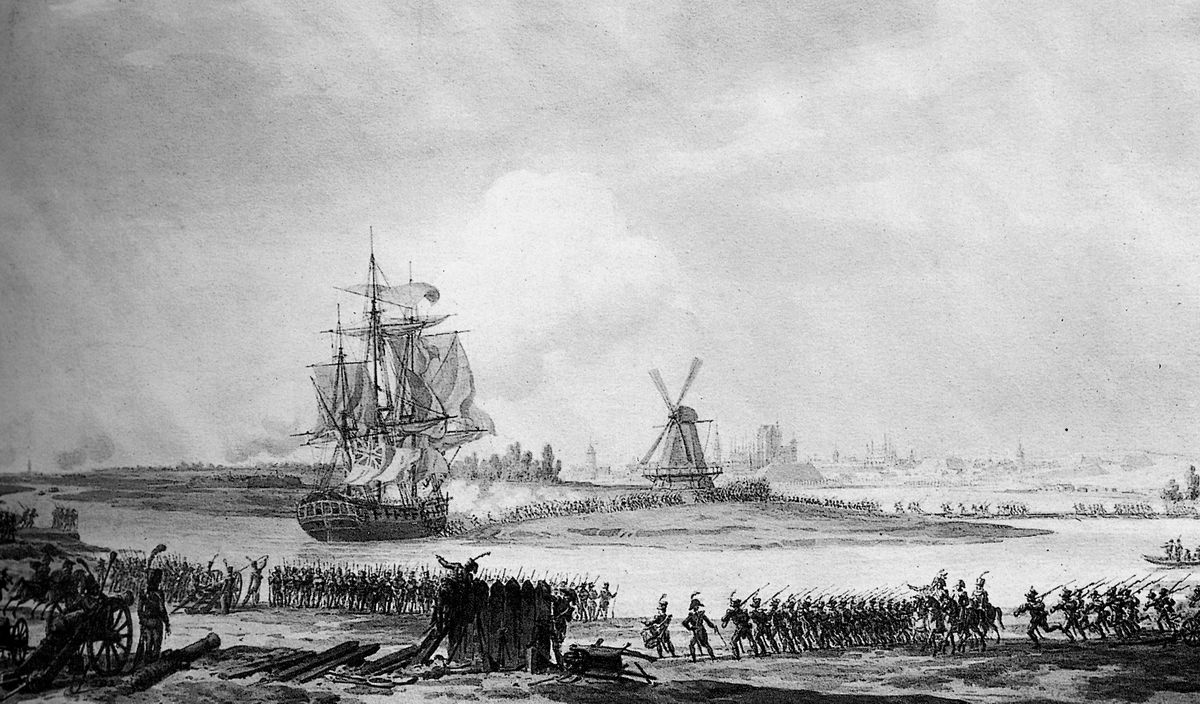

1801 - Tripoli declares war on the United States for not increasing the annual tribute paid as protection money to prevent raids on its ships. Within a week, a squadron with USS President, USS Philadelphia and USS Essex sets sail to protect American interests.

In May, Commodore Richard Dale selected President as his flagship for the assignment in the Mediterranean. Dale's orders were to present a show of force off Algiers, Tripoli, and Tunis and maintain peace with promises of tribute. Dale was authorized to commence hostilities at his discretion if any Barbary State had declared war by the time of his arrival. Dale's squadron consisted of President, Philadelphia, Essex, and Enterprise. The squadron arrived at Gibraltar on 1 July; President and Enterprise quickly continued to Algiers, where their presence convinced the regent to withdraw threats he had made against American merchant ships. President and Enterprise subsequently made appearances at Tunis and Tripoli before President arrived at Malta on 16 August to replenish drinking water supplies.

Blockading the harbor of Tripoli on 24 August, President captured a Greek vessel with Tripolitan soldiers aboard. Dale negotiated an exchange of prisoners that resulted in the release of several Americans held captive in Tripoli.[27][28] President arrived at Gibraltar on 3 September. Near Mahón in early December, President struck a large rock while traveling at 6 knots (11 km/h; 6.9 mph). The impact brought Dale on deck and he successfully navigated President out of danger. An inspection revealed that the impact had twisted off a short section of her keel. President remained in the Mediterranean until March 1802; she departed for the United States and arrived on 14 April.

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

1807 Boats of HMS Spartan (38), Cptn. Jahleel Brenton, repulsed by a polacca off Nice.

HMS Spartan was a Royal Navy 38-gun fifth-rate frigate, launched at Rochester in 1806. During the Napoleonic Wars she was active in the Adriatic and in the Ionian Islands. She then moved to the American coast during the War of 1812, where she captured a number of small vessels, including a US Revenue Cutter and a privateer, the Dart. She then returned to the Mediterranean, where she remained for a few years. She went on to serve off the American coast again, and in the Caribbean, before being broken up in 1822.

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

1812 HMS Thames (32), Cptn. Charles Napier, and HMS Pilot (18), Cptn. John Toup Nicholas took 29 vessels at Port Sapri, Calabria. Most were destroyed by a gale during the night.

HMS Thames (1805) was another 32-gun fifth rate, launched in 1805 and broken up in 1816.

HMS Pilot (1807) was an 18-gun Cruizer-class brig-sloop launched in 1807 and sold in 1828. She became a whaler, making five whale fishing voyages between 1830 and 1842; she was last listed in 1844.

1832 – Launch of HMS Cockatrice was a six-gun schooner, the name ship of her class, built for the Royal Navy during the 1830s.

HMS Cockatrice was a six-gun schooner, the name ship of her class, built for the Royal Navy during the 1830s. She was sold for scrap in 1858.

Description

Cockatrice had a length at the gundeck of 80 feet (24.4 m) and 64 feet 2 inches (19.6 m) at the keel. She had a beam of 23 feet 4 inches (7.1 m), a draught of about 9 feet 5 inches (2.9 m) and a depth of hold of 9 feet 10 inches (3.0 m). The ship's tonnage was 181 78/94 tons burthen. The Cockatrice class was armed with two 6-pounder cannon and four 12-pounder carronades. The ships had a crew of 33–42 officers and ratings.

Construction and career

Cockatrice, the second ship of her name to serve in the Royal Navy, was ordered on 11 September 1828, laid down in July 1831 at Pembroke Dockyard, Wales, and launched on 14 May 1832. She was completed on 15 September 1832 at Plymouth Dockyard.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Cockatrice_(1832)

1836 - Congress authorizes the U.S. Exploring Expedition to conduct an exploration of the Pacific Ocean and South Seas, making the first major US scientific expedition overseas. Lt. Charles Wilkes leads the expedition to survey South America, Antarctica, the Far East, and the North Pacific in his flagship USS Vincennes.

The United States Exploring Expedition of 1838–1842 was an exploring and surveying expedition of the Pacific Ocean and surrounding lands conducted by the United States. The original appointed commanding officer was Commodore Thomas ap Catesby Jones. Funding for the original expedition was requested by President John Quincy Adams in 1828, however, Congress would not implement funding until eight years later. In May 1836, the oceanic exploration voyage was finally authorized by Congress and created by President Andrew Jackson.

The expedition is sometimes called the "U.S. Ex. Ex." for short, or the "Wilkes Expedition" in honor of its next appointed commanding officer, United States Navy Lieutenant Charles Wilkes. The expedition was of major importance to the growth of science in the United States, in particular the then-young field of oceanography. During the event, armed conflict between Pacific islanders and the expedition was common and dozens of natives were killed in action, as well as a few Americans.

Vincennes at Disappointment Bay, Antarctica, early 1840

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

1845 - SS Spitfire, of New Orleans, captured on the coast of Africa, under American flag and the captain indicted in Boston

1919 - The Marine detachment from USS Arizona (BB 39) guards the U.S. consulate at Constantinople, Turkey, during the Greek occupation of the city.

1927 – Launch of Cap Arcona, named after Cape Arkona on the island of Rügen, was a large German ocean liner and the flagship of the Hamburg Südamerikanische Dampfschifffahrts-Gesellschaft ("Hamburg-South America Line").

Cap Arcona, named after Cape Arkona on the island of Rügen, was a large German ocean liner and the flagship of the Hamburg Südamerikanische Dampfschifffahrts-Gesellschaft ("Hamburg-South America Line"). She took her maiden voyage on 29 October 1927, carrying passengers and cargo between Germany and the east coast of South America, and in her time was the largest and quickest ship on the route.

In 1940 the Kriegsmarine requisitioned her as an accommodation ship. In 1942 she served as the set for the German propaganda feature film Titanic. In 1945 she evacuated almost 26,000 German soldiers and civilians from East Prussia before the advance of the Red Army.

Cap Arcona's final use was as a prison ship. In May 1945 she was heavily laden with prisoners from Nazi concentration camps when the Royal Air Force sank her, killing about 5,000 people; with more than 2,000 further casualties in the sinkings of the accompanying vessels of the prison fleet; Deutschland and Thielbek. This was one of the biggest single-incident maritime losses of life in the Second World War, the largest being the wartime sinking of the German evacuation liner Wilhelm Gustloff in January 1945 in World War II by a Soviet Navy submarine, with an estimated loss of about 9,400 people

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

1944 - USS Bonefish (SS 223) attacks a Japanese convoy bound for Sibitu Passage, Borneo, and sinks Japanese destroyer Inazuma near TawiTawi, east of Borneo and survives counter-attacks by Japanese destroyer Hibiki. Also on this date, USS Aspro (SS 309) and USS Bowfin (SS 287) attack a Japanese convoy and sinks cargo ship BisanMaru.

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

1945 - German submarine (U 858) arrives at Cape May, Del., after surrendering at sea four days earlier. USS bury (DE 133) and USS Pope (DE 134) arrive later that day, take over the boat, place U.S. Navy crew on board, and remove 1/2 of her German crew, including three of her four officers. (U 858) is later scuttled off the coast of New England during torpedo trials.

bury (DE 133) and USS Pope (DE 134) arrive later that day, take over the boat, place U.S. Navy crew on board, and remove 1/2 of her German crew, including three of her four officers. (U 858) is later scuttled off the coast of New England during torpedo trials.

German submarine U-858 was a Type IXC/40 U-boat of Nazi Germany's Kriegsmarine during World War II. She was ordered on 5 June 1941, laid downon 11 December 1942 and launched on 30 September 1943. She had one commander for her three patrols, Kapitänleutnant Thilo Bode.

U-858 after her surrender in May 1945

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

Other Events on 14 May

1695 - Launch of french Fougueux 50 guns (designed and built by Blaise Pangalo, launched 14 May 1695 at Brest) – captured by the English in 1696, sank 1696

1717 - May 14 or 15 - Danish attack on Göteborg is defeated

1757 HMS Antelope (54), Cptn. Alexander Arthur Hood, drove ashore and wrecked Aquilon (50) in Audierne Bay.

HMS Antelope was a 50-gun fourth rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, launched at Rotherhithe on 13 March 1703. She was rebuilt once during her career, and served in the Seven Years' War and the American Revolutionary War.

Orders were issued on 9 January 1738 for Antelope to be taken to pieces and rebuilt according to the 1733 proposals of the 1719 Establishment at Woolwich, from where she was relaunched on 27 January 1741.

Scale: 1:48. Plan showing the body plan from midships to bow, body plan from midships to stern with stern board decoration, sheer lines with some inboard detail and figurehead, and longitudinal half-breadth with some lower deck detail for Antelope (1703), a 50-gun Fourth Rate two-decker. This may be the ship as she was when in Plymouth Dockyard in 1713. An attached letter (not scanned) lays out the dimensions of the ship, as taken at Plymouth on 7 March 1713

HMS Antelope (1703) - Wikipedia

1757 - Aquilon 42, later 48 guns (launched 16 March 1741 at Toulon, designed and built by Jean-Armand Levasseur) – wrecked 14 May 1757.

1776 – Launch of HMS Romulus, a Roebuck-class ship was a class of twenty 44-gun sailing two-decker warships of the Royal Navy.

Roebuck-class ship - Wikipedia

1778 – Launch of HMS Janus was a 44-gun Roebuck-class fifth rate of the Royal Navy.

HMS Janus was a 44-gun Roebuck-class fifth rate of the Royal Navy.

From May 1780 she was under the command of Captain Horatio Nelson, though he was superseded by September that year.

In 1793 she was under the command of Captain Sandford Tatham

Loss

HMS Dromedary was wrecked on the Parasol Rocks, Trinidad on 10 August 1800. Her entire complement survived.

Scale: 1:48. Plan showing the body plan with stern board outline, sheer lines with inboard detail, and longitudinal half-breadth for Janus (1778), a 44-gun Fifth Rate, two-decker, as built at Limehouse by Mr Batson. The plan was possibly draughted at Deptford Dockyard as Janus was completed there between May and August 1778

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Janus_(1778)

1781 HMS Nonsuch (64), Cptn. Sir James Wallace, engaged Actif (74).

On 14 May 1781, on the homeward voyage, while scouting ahead, Nonsuch chased and brought to action the French 74-gun Actif, hoping to detain her until some others of the fleet came up. However, Actif was able to repulse Nonsuch, causing her to suffer 26 men killed and 64 wounded, and continued on to Brest.

Scale: 1:48. Plan showing the body plan, sheer lines, and longitudinal half-breadth for Ruby (1776) and Nonsuch (1774), and later for Vigilant (1774), Eagle (1774), and America (1777), all 64-gun Third Rate, two-deckers. Signed by John Williams [Surveyor of the Navy, 1765-1784]

HMS Nonsuch (1774) - Wikipedia

1801 - Tripoli declares war on the United States for not increasing the annual tribute paid as protection money to prevent raids on its ships. Within a week, a squadron with USS President, USS Philadelphia and USS Essex sets sail to protect American interests.

In May, Commodore Richard Dale selected President as his flagship for the assignment in the Mediterranean. Dale's orders were to present a show of force off Algiers, Tripoli, and Tunis and maintain peace with promises of tribute. Dale was authorized to commence hostilities at his discretion if any Barbary State had declared war by the time of his arrival. Dale's squadron consisted of President, Philadelphia, Essex, and Enterprise. The squadron arrived at Gibraltar on 1 July; President and Enterprise quickly continued to Algiers, where their presence convinced the regent to withdraw threats he had made against American merchant ships. President and Enterprise subsequently made appearances at Tunis and Tripoli before President arrived at Malta on 16 August to replenish drinking water supplies.

Blockading the harbor of Tripoli on 24 August, President captured a Greek vessel with Tripolitan soldiers aboard. Dale negotiated an exchange of prisoners that resulted in the release of several Americans held captive in Tripoli.[27][28] President arrived at Gibraltar on 3 September. Near Mahón in early December, President struck a large rock while traveling at 6 knots (11 km/h; 6.9 mph). The impact brought Dale on deck and he successfully navigated President out of danger. An inspection revealed that the impact had twisted off a short section of her keel. President remained in the Mediterranean until March 1802; she departed for the United States and arrived on 14 April.

USS President (1800) - Wikipedia

First Barbary War - Wikipedia

1807 Boats of HMS Spartan (38), Cptn. Jahleel Brenton, repulsed by a polacca off Nice.

HMS Spartan was a Royal Navy 38-gun fifth-rate frigate, launched at Rochester in 1806. During the Napoleonic Wars she was active in the Adriatic and in the Ionian Islands. She then moved to the American coast during the War of 1812, where she captured a number of small vessels, including a US Revenue Cutter and a privateer, the Dart. She then returned to the Mediterranean, where she remained for a few years. She went on to serve off the American coast again, and in the Caribbean, before being broken up in 1822.

HMS Spartan (1806) - Wikipedia

1812 HMS Thames (32), Cptn. Charles Napier, and HMS Pilot (18), Cptn. John Toup Nicholas took 29 vessels at Port Sapri, Calabria. Most were destroyed by a gale during the night.

HMS Thames (1805) was another 32-gun fifth rate, launched in 1805 and broken up in 1816.

HMS Pilot (1807) was an 18-gun Cruizer-class brig-sloop launched in 1807 and sold in 1828. She became a whaler, making five whale fishing voyages between 1830 and 1842; she was last listed in 1844.

1832 – Launch of HMS Cockatrice was a six-gun schooner, the name ship of her class, built for the Royal Navy during the 1830s.

HMS Cockatrice was a six-gun schooner, the name ship of her class, built for the Royal Navy during the 1830s. She was sold for scrap in 1858.

Description

Cockatrice had a length at the gundeck of 80 feet (24.4 m) and 64 feet 2 inches (19.6 m) at the keel. She had a beam of 23 feet 4 inches (7.1 m), a draught of about 9 feet 5 inches (2.9 m) and a depth of hold of 9 feet 10 inches (3.0 m). The ship's tonnage was 181 78/94 tons burthen. The Cockatrice class was armed with two 6-pounder cannon and four 12-pounder carronades. The ships had a crew of 33–42 officers and ratings.

Construction and career

Cockatrice, the second ship of her name to serve in the Royal Navy, was ordered on 11 September 1828, laid down in July 1831 at Pembroke Dockyard, Wales, and launched on 14 May 1832. She was completed on 15 September 1832 at Plymouth Dockyard.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Cockatrice_(1832)

Naval/Maritime History - 27th of August - Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History 12 May 1808 - HMS Tartar (32), Cptn. G. E. B. Bettesworth (Killed in Action), and boats engaged at Bergen. HMS Tartar left Leith roads on 10 May 1807 and arrived off Bergen on the 12th, but heavy fog prevented her from getting closer...

shipsofscale.com

1836 - Congress authorizes the U.S. Exploring Expedition to conduct an exploration of the Pacific Ocean and South Seas, making the first major US scientific expedition overseas. Lt. Charles Wilkes leads the expedition to survey South America, Antarctica, the Far East, and the North Pacific in his flagship USS Vincennes.

The United States Exploring Expedition of 1838–1842 was an exploring and surveying expedition of the Pacific Ocean and surrounding lands conducted by the United States. The original appointed commanding officer was Commodore Thomas ap Catesby Jones. Funding for the original expedition was requested by President John Quincy Adams in 1828, however, Congress would not implement funding until eight years later. In May 1836, the oceanic exploration voyage was finally authorized by Congress and created by President Andrew Jackson.

The expedition is sometimes called the "U.S. Ex. Ex." for short, or the "Wilkes Expedition" in honor of its next appointed commanding officer, United States Navy Lieutenant Charles Wilkes. The expedition was of major importance to the growth of science in the United States, in particular the then-young field of oceanography. During the event, armed conflict between Pacific islanders and the expedition was common and dozens of natives were killed in action, as well as a few Americans.

Vincennes at Disappointment Bay, Antarctica, early 1840

United States Exploring Expedition - Wikipedia

1845 - SS Spitfire, of New Orleans, captured on the coast of Africa, under American flag and the captain indicted in Boston

1919 - The Marine detachment from USS Arizona (BB 39) guards the U.S. consulate at Constantinople, Turkey, during the Greek occupation of the city.

1927 – Launch of Cap Arcona, named after Cape Arkona on the island of Rügen, was a large German ocean liner and the flagship of the Hamburg Südamerikanische Dampfschifffahrts-Gesellschaft ("Hamburg-South America Line").

Cap Arcona, named after Cape Arkona on the island of Rügen, was a large German ocean liner and the flagship of the Hamburg Südamerikanische Dampfschifffahrts-Gesellschaft ("Hamburg-South America Line"). She took her maiden voyage on 29 October 1927, carrying passengers and cargo between Germany and the east coast of South America, and in her time was the largest and quickest ship on the route.

In 1940 the Kriegsmarine requisitioned her as an accommodation ship. In 1942 she served as the set for the German propaganda feature film Titanic. In 1945 she evacuated almost 26,000 German soldiers and civilians from East Prussia before the advance of the Red Army.

Cap Arcona's final use was as a prison ship. In May 1945 she was heavily laden with prisoners from Nazi concentration camps when the Royal Air Force sank her, killing about 5,000 people; with more than 2,000 further casualties in the sinkings of the accompanying vessels of the prison fleet; Deutschland and Thielbek. This was one of the biggest single-incident maritime losses of life in the Second World War, the largest being the wartime sinking of the German evacuation liner Wilhelm Gustloff in January 1945 in World War II by a Soviet Navy submarine, with an estimated loss of about 9,400 people

SS Cap Arcona - Wikipedia

1944 - USS Bonefish (SS 223) attacks a Japanese convoy bound for Sibitu Passage, Borneo, and sinks Japanese destroyer Inazuma near TawiTawi, east of Borneo and survives counter-attacks by Japanese destroyer Hibiki. Also on this date, USS Aspro (SS 309) and USS Bowfin (SS 287) attack a Japanese convoy and sinks cargo ship BisanMaru.

USS Bonefish (SS-223) - Wikipedia

1945 - German submarine (U 858) arrives at Cape May, Del., after surrendering at sea four days earlier. USS

bury (DE 133) and USS Pope (DE 134) arrive later that day, take over the boat, place U.S. Navy crew on board, and remove 1/2 of her German crew, including three of her four officers. (U 858) is later scuttled off the coast of New England during torpedo trials.

bury (DE 133) and USS Pope (DE 134) arrive later that day, take over the boat, place U.S. Navy crew on board, and remove 1/2 of her German crew, including three of her four officers. (U 858) is later scuttled off the coast of New England during torpedo trials.German submarine U-858 was a Type IXC/40 U-boat of Nazi Germany's Kriegsmarine during World War II. She was ordered on 5 June 1941, laid downon 11 December 1942 and launched on 30 September 1943. She had one commander for her three patrols, Kapitänleutnant Thilo Bode.

U-858 after her surrender in May 1945

German submarine U-858 - Wikipedia

Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

15 May 1812 – Launch of French Aréthuse, a 46-gun 18-pounder frigate of the French Navy.

The Aréthuse was a 46-gun 18-pounder frigate of the French Navy. She served during the Napoleonic Wars, taking part in a major single-ship action. Much later she took part in the conquest of Algeria, and ended her days as a coal depot in Brest.

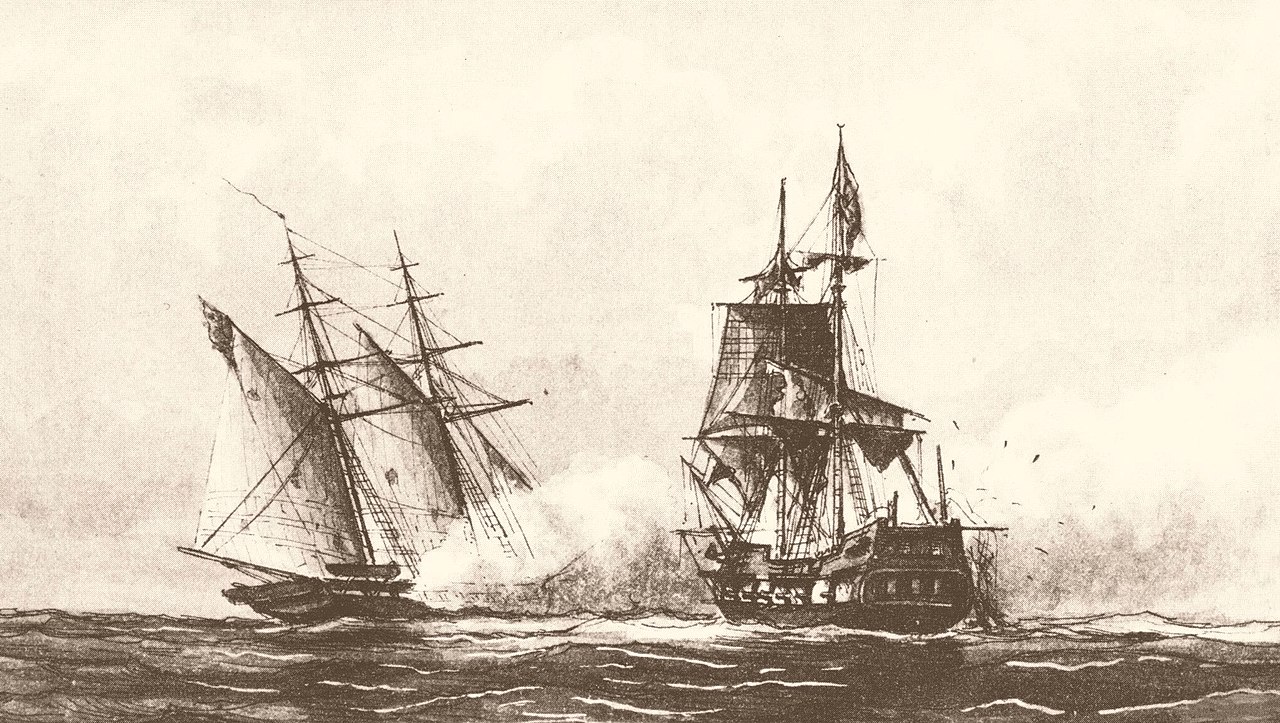

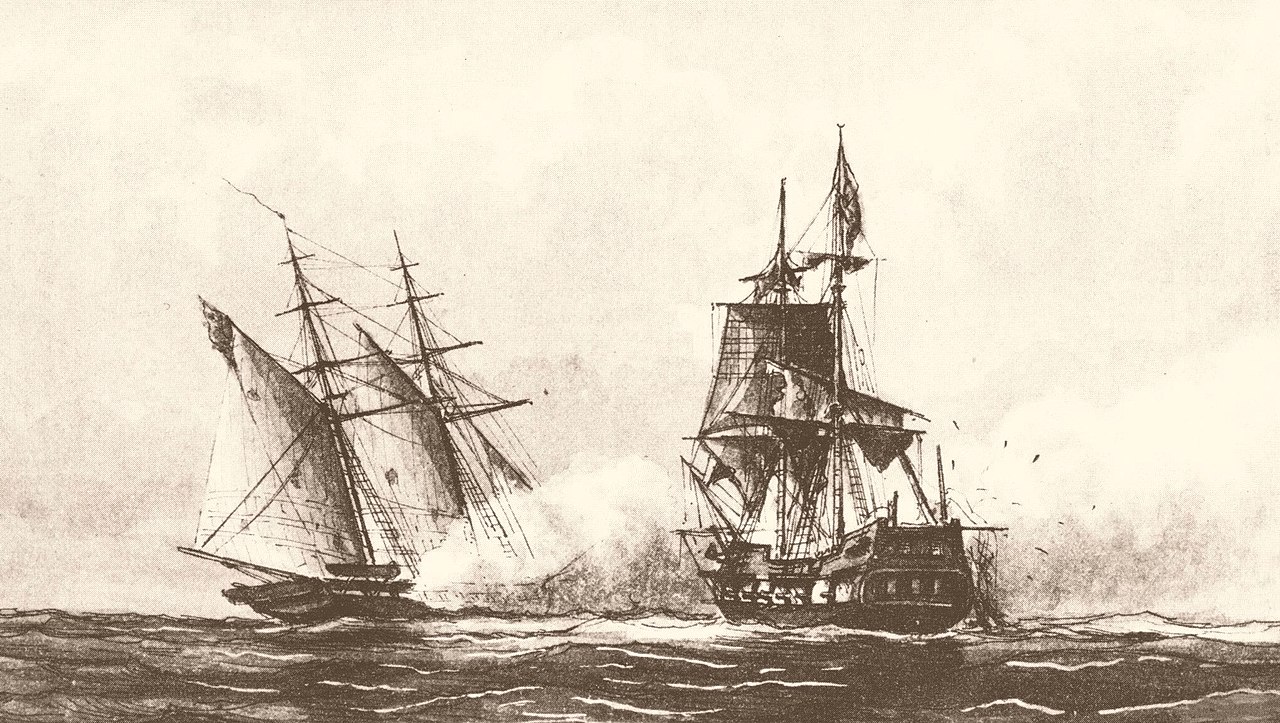

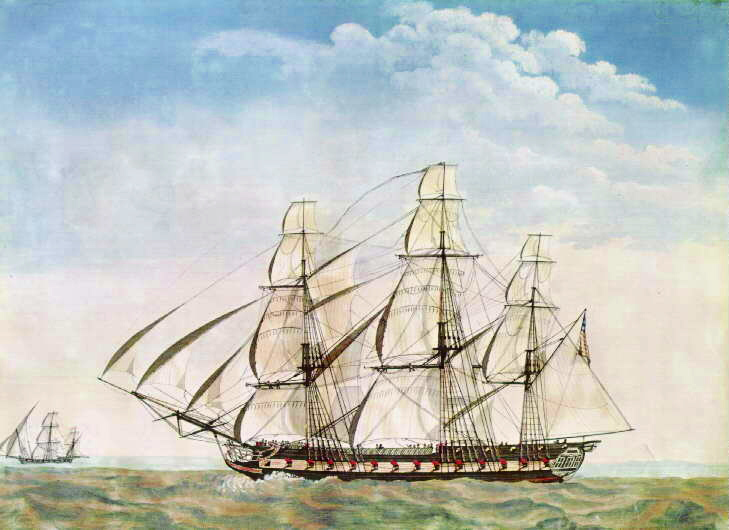

A depiction of the battle between the French frigate Aréthuse and the H.M.S. Amelia off the shores of Guinea, 7 February 1813.

Construction

Aréthuse was laid down at Nantes in 1807 and launched on 15 May 1812.

Career

Cruise off West Africa, 1812-1813

Main article: Action of 7 February 1813

On 25 November 1812 the frigates Aréthuse (Captain Pierre Bouvet) and Rubis sailed from Nantes to intercept British trade off West Africa. In January, having captured a Portuguese ship, La Serra, they reached Cap-Vert. They also captured Little Belt, J. Wilson, master, sailing from Altea to London, Friends, Houston, master, sailing from Teneriffe to Belfast, and a Spanish brig sailing from Majorca to Puerto Rico. The French put the masters and crews on Delphina, a Portuguese they had captured and plundered. Delphina arrived at Pernambuco on 31 January.

On 27 January 1813, Aréthuse intercepted the brig HMS Daring (Lieutenant Pascoe) off Tamara (one of the Iles de Los off Guinea). Pascoe ran Daring aground and set fire to her to avoid her capture. The French managed to take part of her crew prisoner but released them against their parole and put them in a boat. Pascoe and those of his men who had escaped capture sailed to the Sierra Leone River, where they arrived the next day. There they reported the presence of the French frigates to HMS Amelia (Captain Frederick Paul Irby).

In the night of 5 February, a storm threw Rubis ashore, wrecking her. The same storm damaged Aréthuse' rudder. Rubis was abandoned and set afire, while Aréthuse effect her repairs.

HMS Amelia in action with the French Frigate Aréthuse, 1813, by John Christian Schetky, 1852

On 6 February, HMS Amelia, guided and reinforced by sailors from Daring, attacked Aréthuse. A furious, 4-hour night battle followed. Aréthuse and Amelia disabled each other by shooting at their sails and rigging. Eventually the ships parted, neither able to gain the upper hand, and both with heavy casualties: Amelia had 46 killed and 51 wounded; Aréthuse suffered over 20 killed and 88 wounded, and 30 round shot had struck her hull on the starboard side below the quarter deck.

Aréthuse returned to the wreck of Rubis to gather her crew, and returned to France. Soon afterwards Aréthuse captured the British privateer Cerberus, and arrived back in St Malo on 19 April having taken 15 prizes.

Later life and disposal

She took part in the Invasion of Algiers in 1830 as a transport. In 1833, she was razeed into a corvette. She was decommissioned in 1861 and used as a coal depot in Brest.

A dramatic night scene depiciting the battle between the French 'Arethuse', in the left foreground, and the British 'Amelia' near Guinea. The battle resulted in a stalemate, but both ships returned to port claiming victory. Inscription reads: 'Engagement between His Majesty's Ship Amelia carrying 48 Guns and 300 Men - and L'Arethuse, (French Frigate) carrying 48 Guns, and 380 Men, Off the Isle de Loss, on the Coast of Africa, On the Night of The 7th of February 1813 - The Rubus (Arethuse's Consort) carrying 48 Guns & 375 Men, having been in sight previous to the Action.' In 'The Royal Navy - a history' (Vol. 5, p521), William Laird Clowes lists 'Amelia's' guns as 24 and crew as 319 "men and boys" and 'Arethuse's' guns as 22 and crew as "about 340 men"

Model of a Pallas-class frigate

The Pallas class constituted the standard design of 40-gun frigates of the French Navy during the Napoleonic Empire period. Jacques-Noël Sanédesigned them in 1805, as a development of his seven-ship Hortense class of 1802, and over the next eight years the Napoléonic government ordered in total 62 frigates to be built to this new design. Of these some 54 were completed, although ten of them were begun for the French Navy in shipyards within the French-occupied Netherlands or Italy, which were then under French occupation; these latter ships were completed for the Netherlands or Austrian navies after 1813.

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

15 May 1812 – Launch of French Aréthuse, a 46-gun 18-pounder frigate of the French Navy.

The Aréthuse was a 46-gun 18-pounder frigate of the French Navy. She served during the Napoleonic Wars, taking part in a major single-ship action. Much later she took part in the conquest of Algeria, and ended her days as a coal depot in Brest.

A depiction of the battle between the French frigate Aréthuse and the H.M.S. Amelia off the shores of Guinea, 7 February 1813.

Construction

Aréthuse was laid down at Nantes in 1807 and launched on 15 May 1812.

Career

Cruise off West Africa, 1812-1813

Main article: Action of 7 February 1813

On 25 November 1812 the frigates Aréthuse (Captain Pierre Bouvet) and Rubis sailed from Nantes to intercept British trade off West Africa. In January, having captured a Portuguese ship, La Serra, they reached Cap-Vert. They also captured Little Belt, J. Wilson, master, sailing from Altea to London, Friends, Houston, master, sailing from Teneriffe to Belfast, and a Spanish brig sailing from Majorca to Puerto Rico. The French put the masters and crews on Delphina, a Portuguese they had captured and plundered. Delphina arrived at Pernambuco on 31 January.

On 27 January 1813, Aréthuse intercepted the brig HMS Daring (Lieutenant Pascoe) off Tamara (one of the Iles de Los off Guinea). Pascoe ran Daring aground and set fire to her to avoid her capture. The French managed to take part of her crew prisoner but released them against their parole and put them in a boat. Pascoe and those of his men who had escaped capture sailed to the Sierra Leone River, where they arrived the next day. There they reported the presence of the French frigates to HMS Amelia (Captain Frederick Paul Irby).

In the night of 5 February, a storm threw Rubis ashore, wrecking her. The same storm damaged Aréthuse' rudder. Rubis was abandoned and set afire, while Aréthuse effect her repairs.

HMS Amelia in action with the French Frigate Aréthuse, 1813, by John Christian Schetky, 1852

On 6 February, HMS Amelia, guided and reinforced by sailors from Daring, attacked Aréthuse. A furious, 4-hour night battle followed. Aréthuse and Amelia disabled each other by shooting at their sails and rigging. Eventually the ships parted, neither able to gain the upper hand, and both with heavy casualties: Amelia had 46 killed and 51 wounded; Aréthuse suffered over 20 killed and 88 wounded, and 30 round shot had struck her hull on the starboard side below the quarter deck.

Aréthuse returned to the wreck of Rubis to gather her crew, and returned to France. Soon afterwards Aréthuse captured the British privateer Cerberus, and arrived back in St Malo on 19 April having taken 15 prizes.

Later life and disposal

She took part in the Invasion of Algiers in 1830 as a transport. In 1833, she was razeed into a corvette. She was decommissioned in 1861 and used as a coal depot in Brest.

A dramatic night scene depiciting the battle between the French 'Arethuse', in the left foreground, and the British 'Amelia' near Guinea. The battle resulted in a stalemate, but both ships returned to port claiming victory. Inscription reads: 'Engagement between His Majesty's Ship Amelia carrying 48 Guns and 300 Men - and L'Arethuse, (French Frigate) carrying 48 Guns, and 380 Men, Off the Isle de Loss, on the Coast of Africa, On the Night of The 7th of February 1813 - The Rubus (Arethuse's Consort) carrying 48 Guns & 375 Men, having been in sight previous to the Action.' In 'The Royal Navy - a history' (Vol. 5, p521), William Laird Clowes lists 'Amelia's' guns as 24 and crew as 319 "men and boys" and 'Arethuse's' guns as 22 and crew as "about 340 men"

Model of a Pallas-class frigate

The Pallas class constituted the standard design of 40-gun frigates of the French Navy during the Napoleonic Empire period. Jacques-Noël Sanédesigned them in 1805, as a development of his seven-ship Hortense class of 1802, and over the next eight years the Napoléonic government ordered in total 62 frigates to be built to this new design. Of these some 54 were completed, although ten of them were begun for the French Navy in shipyards within the French-occupied Netherlands or Italy, which were then under French occupation; these latter ships were completed for the Netherlands or Austrian navies after 1813.

French frigate Aréthuse (1812) - Wikipedia

Pallas-class frigate (1808) - Wikipedia

Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

15 May 1839 – Launch of HMS Queen, a 110-gun first-rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, at Portsmouth.

HMS Queen was a 110-gun first-rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, launched on 15 May 1839 at Portsmouth. She was the last purely sailing battleship to be completed - subsequent ones had steam engines as well although all British battleships were constructed with sailing rig until the 1870s.

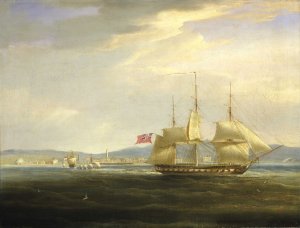

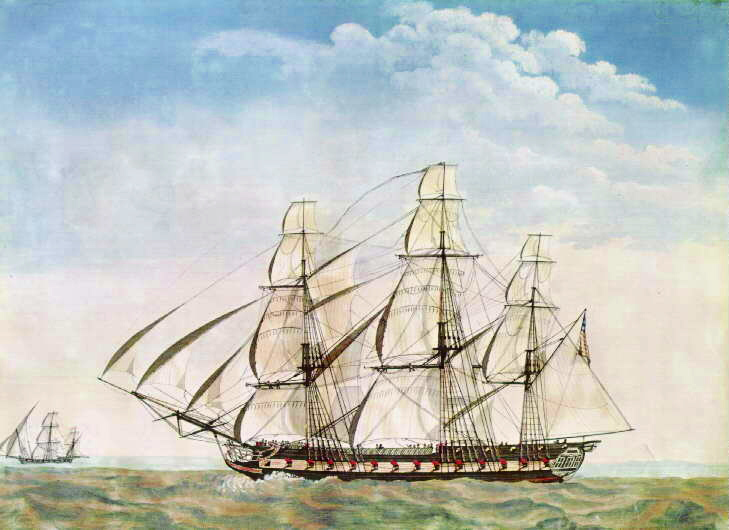

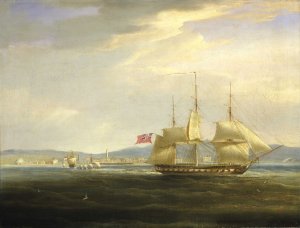

HMS Queen, Flagship of Vice Admiral Sir Edward Rich Owen, Commander-in-Chief of the Mediterranean fleet, leaving Malta (Robert Strickland Thomas, 1842)

Ordered

She was ordered in 1827 under the name Royal Frederick, but renamed on 12 April 1839 while still on the stocks in honour of the recently enthroned Queen Victoria. She was originally ordered as the final ship of the broadened Caledonia class, but on 3 September 1833 she was re-ordered to a new design by Sir William Symonds.