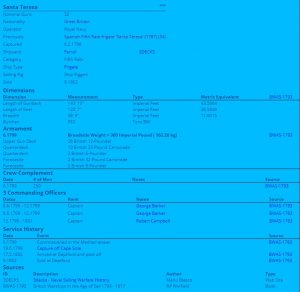

Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

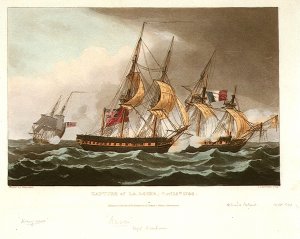

4 February 1807 - HMS Lark (1794 - 16), Cptn. Robert Nicholas, and boats at Zispata Bay. Silenced a battery and engaged a convoy with 3 small escorts. 1 enemy was taken but 2 earlier prizes ran aground and were burnt.

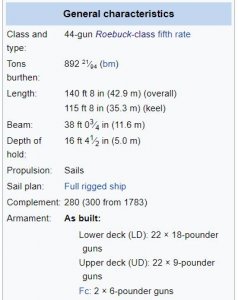

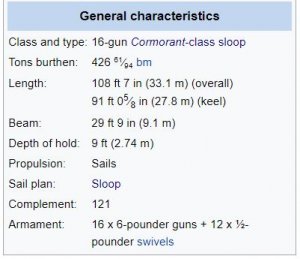

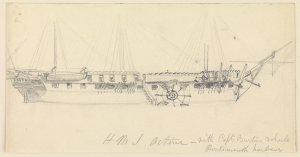

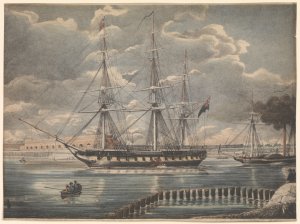

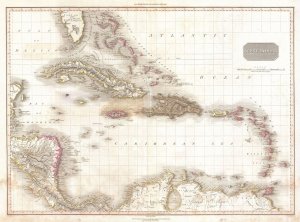

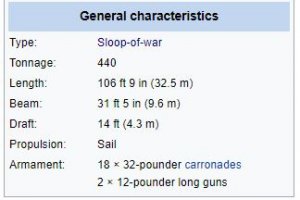

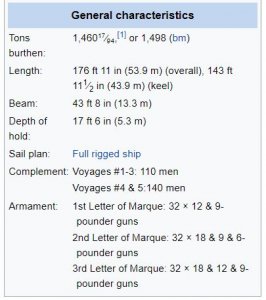

HMS Lark was a 16-gun ship sloop of the Cormorant class, launched in 1794 at Northfleet. She served primarily in the Caribbean, where she took a number of prizes, some after quite intensive action. Lark foundered off San Domingo in August 1809, with the loss of her captain and almost all her crew.

French Revolutionary Wars

Lark was commissioned in March 1794 under Commander Josias Rowley. Later that year Commander Francis Austen, who would go on to rise to the rank of Admiral of the Fleet, served on her when she was part of a fleet that evacuated British troops from Ostend and Nieuwpoort after the French captured the Netherlands. In 1795, the Lark was part of the squadron under Commodore Payne that escorted Princess Caroline of Brunswick to England. That same year she was part of the British naval force that supported the invasion of France by a force of French émigrés.

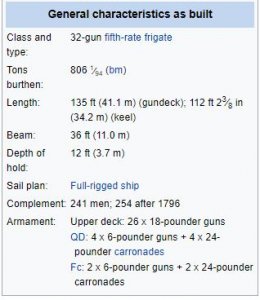

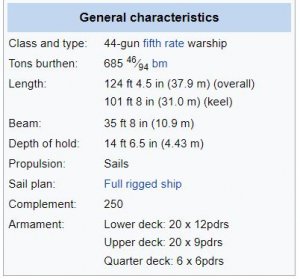

In January 1795 Commander William Ogilvy recommissioned her. On 21 March 1796, Lark joined the 32-gun frigate Ceres, Captain James Newman-Newman, in providing support to an unsuccessful attack by British troops from Port-au-Prince on the town and fort of Léogane on the island of Hispaniola.

Commander James Hayes was appointed captain of Lark in 1798. In late 1798 or early 1799, while on the Jamaica station, boats from the 98-gun second rate Queen and Lark, under the temporary command of Lieutenant Hugh Cooke, cut out a schooner of four guns from Port Nieu in the West Indies. During this period, Lark, with Jamaica captured two merchant vessels and destroyed one, and Lark alone destroyed another.

In April 1799 Commander John Wentworth Loring took command. Lark then captured another schooner. Between 12 February and 21 May 1799, Larkcaptured two small privateers, a French schooner and a Spanish lateen-rigged vessel of one 6-pounder and two swivel guns, as well as seven merchant vessels. At some point between 26 June and October, Lark captured the American brig Sally, which was sailing from St. Thomas to Havana with 23 "new Negroes".

Between 21 July and October Lark captured six more vessels:

Between 9 and 20 March 1800, Lark took or destroyed six privateers and other small vessels. These included the French schooner Creole de Cuba, in ballast and destroyed on 9 March, a canoe loaded with timber taken on 14 March, the sloop Lively recaptured that same day, a French privateer destroyed on 15 March, a Spanish sloop in ballast, destroyed on 19 March, and a French schooner loaded with salt and taken on 20 March.

The most intense action amongst these six captures occurred off Santiago de Cuba on 14 March when Loring saw a privateer schooner in a bay. He sent boats to bring her out but the enemy had established fortifications on the two heights that guarded the bay. From there, the enemy was able to repulse the attack, killing the lieutenant in command of the boats. Lark then put ashore a landing party some ten miles down the coast. This landing party marched up the coast and attacked the privateer from the rear with the result that when Loring led boats back into the bay he found the landing party had already captured the quarry. The privateer had two carriage guns and Loring destroyed her rather than bring her out.

At some point during or after this, Lark captured or destroyed several more vessels. The list below may, but probably does not, overlap the list for the period 9 to 20 March.

Lark's next action occurred on 13 September 1801. With Lieutenant James Johnstone as acting captain, Lark chased a Spanish privateer schooner along the coast of Cuba until evening, when the schooner took refuge within the Portillo Reefs. Johnstone sent his yawl and cutter, each with sixteen men, including officers, to capture her. The privateer, which was armed with a long 8-pounder and two 4-pounders, opened fire on the boarding party. Still, the British prevailed, though they lost one man killed and a midshipman and 12 sailors wounded. The Spanish lost 21 dead, including their captain Joseph Callie, and six wounded; Lark took the remainder of the 45 man crew prisoner. The privateer was the Esperanza out of Santiago, and in the previous month she had taken the British sloop Eliza and the brig Betsey.

In April 1802 Edward Pelham Brenton took command. In July James Tippet may have been appointed to command, but on 4 July Lark left Jamaica for England. On 15 August, two days before she reached Plymouth, Lark encountered the brig Jane. Jane had apparently run out of food and water so Brenton provided her with some. After reaching Plymouth, Lark sailed the next day to Woolwich to be paid off.

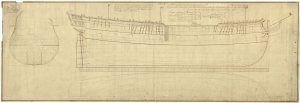

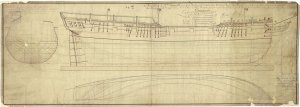

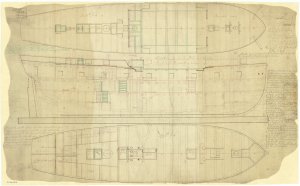

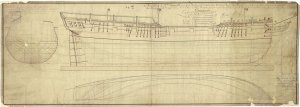

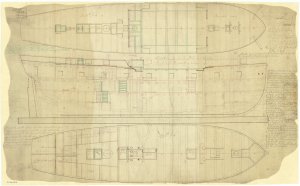

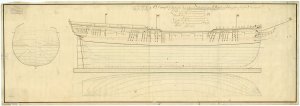

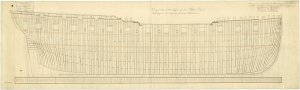

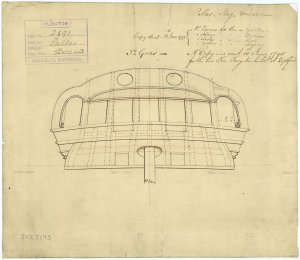

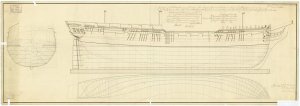

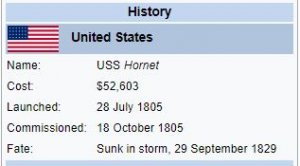

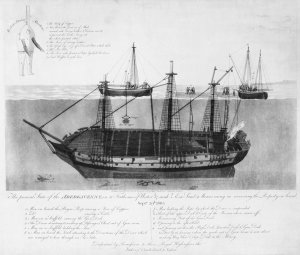

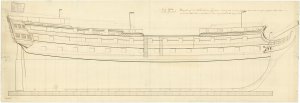

Scale: 1:48. Plan showing the quarterdeck and forecastle, inboard profile, and upper deck for Hornet (1794), Cormorant (1794), Favourite (1794), Lynx (1794), Hazard (1794), Lark (1794), and Stork (1796), all 16-gun Ship Sloops. The plan was later altered in 1805 and used to build Hyacinth (1806), Herald (1806), Sabrina (1806), Cherub (1806), Minstrel (1807), Blossom (1806), Favourite (1806), Sapphire (1806), Wanderer (1806), Partridge (1809), Tweed (1807), Egeria (1807), Ranger (1807), Anacreon (1813), and Acorn (1807), Rosamond (1807), Fawn (1807), Myrtle (1807), Racoon (1808), and North Star (1810) all modified Cormorant class 16-gun Ship Sloops. The plan was altered again in 1808 while building Hesper (1809). The design for this class is 'similar to the French Ship Amazon' - the French Amazon (captured 1745).

Napoleonic Wars

On 31 May 1803 Lark was under the command of John Tower when she captured the French ship Marianne. On 11 April 1804 there was an announcement that when Lark next arrived at Deal that the prize agents would disburse a distribution of £5000 in prize money to those of her captain and crew who had participated in the capture. There was a second disbursement of £1759 in 1804. Lark also shared part of the proceeds of the capture with the English privateers Star and Polecat.

In May 1804 Lark was under the command of Fredrick Langford who in January 1805 took Lark from Portsmouth, headed for West Africa. In late January or early February he found a Spanish merchant vessel at anchor off the Bay of Senegal and captured her. She was the schooner Camerara, with two guns, though she was pierced for 16, and was carrying a cargo of wine. The Camerara was formerly French and had been a successful privateer at Cayenne under the ownership of Victor Hughes. The Governor of Senegal had intended to present her to her former captain, Victor Hughes, with the aim of using her to harass British trade on this part of the coast of Africa.

On 29 May 1805 Lark was in company with Squirrel off the coast of Guinea when they captured the French merchant brigantine Cecile.

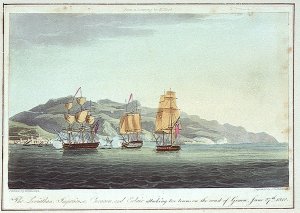

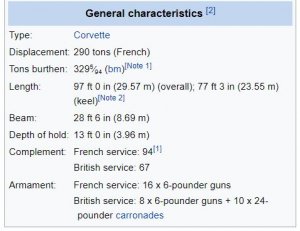

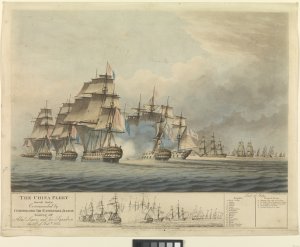

Towards the end of 1806, Lark was escorting six merchantmen from Gorée when by the Savage Islands she came upon a French squadron consisting of five sail of the line, three frigates, a razée and two brig-corvettes. The convoy dispersed and Lark was able to escape and made her way to Cadiz to alert the British fleet there. Lark reached Cadiz on 26 November, and Rear Admiral Sir John Thomas Duckworth immediately took his squadron to try to find the French. The French squadron, under Contre-Admiral Allemand, was part of a French break-out from Brest.

Lark went on to Portsmouth. She then left Portsmouth under the command of Commander Robert Nicholas, bound for the West Indies. On the way, on 19 January 1807, she set off in pursuit of a Spanish schooner. Unfortunately, the schooner was carrying so much sail that a squall capsized her; Lark could not reach the spot where she went down before the schooner's entire crew had already drowned.

Later that January, on the 27th, and after a 14-hour pursuit, Lark captured two Spanish guarda costa (coast guard) vessels sailing from Cartagena to Portobelo. The two vessels were the Postillon (one long 12-pounder gun, two six-pounders, and 76 men), and the Carmen (one 12-pounder, four six pounders, and 72 men).

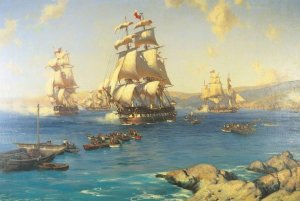

On 4 February Lark was still in company with the two guarda costas when they encountered two gunboats and an armed schooner escorting a Spanish convoy of several small market boats. Lark was able to drive the vessels of the convoy ashore, but the escorts took refuge under the guns of a 4-gun battery in a creek in Bahia Cispata, Colombia. Lark silenced the battery. Nicholas then took his entire crew, less the 20 men he left to guard the two guarda costas, and put them in boats with the aim of capturing the gunboats and the armed schooner. The Spanish gunboats rowed towards the British boats but then retreated as the British drew nearer. Nicholas and three of his men then were wounded while they were capturing the rearmost vessel, a gun boat with one 24-pounder and two 6-pounder guns. Later, Lark had three more men wounded in the continuing action. Nicholas then attempted to pursue the remaining Spanish vessels up a creek but while he was trying to do so, the pilot ran Postillon and Carmen ashore. This forced Nicholas to order their prize crews to burn them, which they did. Postillion blew up and Carmen was solidly aflame when the British last saw her.

On 23 August, Lark, in the company of the Cruizer class brig sloop HMS Ferret, captured the French privateer schooner Mosquito, out of Santo Domingo. She had eight guns and a crew of 58 men.

In 1807, Nicholas became lieutenant governor of Curaçao shortly after the British captured it. When he left, the merchants there gave him a silver plate in appreciation for his efforts in protection of their trade.

In the summer of 1809, Lark participated in the blockade of San Domingo until the city fell on 11 July to Spanish forces and the British under Hugh Lyle Carmichael. The blockading squadron, under Captain William Pryce Cumby in the 64-gun third rate Polyphemus, also included Aurora, Tweed, Sparrow, Thrush, Griffon, Moselle, and Fleur de la Mer. Payment of prize money occurred in January 1826 and October 1832.

Loss

Unfortunately, on 3 August 1809, Lark foundered in a gale off Cape Causada (Point Palenqua), San Domingo. She was at anchor when the gale struck. She set sail at daybreak to get out to sea but while she was shortening sail a squall struck that turned her on her side. At that point a heavy sea struck her and she filled rapidly with water. She sank within 15 minutes, taking most of her crew with her. Some of her crew survived by hanging on to floating wreckage. However, by evening, when the Cruizer-class brig-sloop Moselle arrived, Commander Nicholas and all but three men of her crew of 120 were dead. Moselle then rescued the three survivors. Nicholas had just been promoted to post-captain with orders to command Garland.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Lark_(1794)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cormorant-class_ship-sloop

http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collec...el-324976;browseBy=vessel;vesselFacetLetter=L

https://threedecks.org/index.php?display_type=show_ship&id=5035

4 February 1807 - HMS Lark (1794 - 16), Cptn. Robert Nicholas, and boats at Zispata Bay. Silenced a battery and engaged a convoy with 3 small escorts. 1 enemy was taken but 2 earlier prizes ran aground and were burnt.

HMS Lark was a 16-gun ship sloop of the Cormorant class, launched in 1794 at Northfleet. She served primarily in the Caribbean, where she took a number of prizes, some after quite intensive action. Lark foundered off San Domingo in August 1809, with the loss of her captain and almost all her crew.

French Revolutionary Wars

Lark was commissioned in March 1794 under Commander Josias Rowley. Later that year Commander Francis Austen, who would go on to rise to the rank of Admiral of the Fleet, served on her when she was part of a fleet that evacuated British troops from Ostend and Nieuwpoort after the French captured the Netherlands. In 1795, the Lark was part of the squadron under Commodore Payne that escorted Princess Caroline of Brunswick to England. That same year she was part of the British naval force that supported the invasion of France by a force of French émigrés.

In January 1795 Commander William Ogilvy recommissioned her. On 21 March 1796, Lark joined the 32-gun frigate Ceres, Captain James Newman-Newman, in providing support to an unsuccessful attack by British troops from Port-au-Prince on the town and fort of Léogane on the island of Hispaniola.

Commander James Hayes was appointed captain of Lark in 1798. In late 1798 or early 1799, while on the Jamaica station, boats from the 98-gun second rate Queen and Lark, under the temporary command of Lieutenant Hugh Cooke, cut out a schooner of four guns from Port Nieu in the West Indies. During this period, Lark, with Jamaica captured two merchant vessels and destroyed one, and Lark alone destroyed another.

In April 1799 Commander John Wentworth Loring took command. Lark then captured another schooner. Between 12 February and 21 May 1799, Larkcaptured two small privateers, a French schooner and a Spanish lateen-rigged vessel of one 6-pounder and two swivel guns, as well as seven merchant vessels. At some point between 26 June and October, Lark captured the American brig Sally, which was sailing from St. Thomas to Havana with 23 "new Negroes".

Between 21 July and October Lark captured six more vessels:

- Spanish schooner La Reyna Louisa, from Truxill bound to Havana, laden with nails, paint, white lime, leather, etc.;

- Schooner Aurora, under American colours, from New York bound to Vera Cruz, laden with single sheet tin, pigs (ingots) of tin, dry goods, etc. (Spanish Property);

- Ship America, under American colours, from Providence in America, to Havana, laden with salt; she had already landed part of her cargo at Turk's Island;

- Schooner Betsy, under American colours, from Charleston bound to Havana, laden with sheet and pig lead;

- Schooner Daphne, under American colours, from Philadelphia bound to Havana, laden with dry goods and iron work for sugar mills (Spanish property); and

- Brig Mary, under American colours, from Baltimore bound to Vera Cruz, laden with dry goods (Spanish property).

- Spanish brig Nostra Senora de los Delores. She was of 140 tons, armed with four guns and had a crew of 30 men. She was from Havana bound to Vera Cruz with a cargo of cocoa. Lark was in company with Greyhound and Stork;

- Spanish brig Santo Domingo y San Juan Nepumaceno, taken off Cape Catouche. She was of 110 tons, armed with two guns, and had a crew of ten men. She was carrying a cargo of brandy, wine, oil, olives, and tin;

- Spanish polacca Londre San Antonio de Padua, also taken off Cape Catouche. She was of 120 tons, armed with six guns, and had a crew of 18 men. She was carrying a cargo dry goods, brandy, wine, oil, olives, and tin.

Between 9 and 20 March 1800, Lark took or destroyed six privateers and other small vessels. These included the French schooner Creole de Cuba, in ballast and destroyed on 9 March, a canoe loaded with timber taken on 14 March, the sloop Lively recaptured that same day, a French privateer destroyed on 15 March, a Spanish sloop in ballast, destroyed on 19 March, and a French schooner loaded with salt and taken on 20 March.

The most intense action amongst these six captures occurred off Santiago de Cuba on 14 March when Loring saw a privateer schooner in a bay. He sent boats to bring her out but the enemy had established fortifications on the two heights that guarded the bay. From there, the enemy was able to repulse the attack, killing the lieutenant in command of the boats. Lark then put ashore a landing party some ten miles down the coast. This landing party marched up the coast and attacked the privateer from the rear with the result that when Loring led boats back into the bay he found the landing party had already captured the quarry. The privateer had two carriage guns and Loring destroyed her rather than bring her out.

At some point during or after this, Lark captured or destroyed several more vessels. The list below may, but probably does not, overlap the list for the period 9 to 20 March.

- French brig Voltigeur, which was carrying a cargo of coffee. She was armed with four guns and had a crew of 24 men.

- French schooner Volante in ballast and destroyed;

- French schooner Trompeuse taken while sailing from Jeremie to St. Jago (Santiago de Cuba) with a cargo of salt;

- French schooner Trois Amis taken with a cargo of coffee;

- French sloop of unknown name, taken in ballast;

- French schooner of unknown name taken while sailing from Jeremie to St. Jago with a cargo of salt;

- American schooner Freedom taken while sailing from Turk's Island to St. Jago with a cargo of salt;

- Spanish sloop Fortune, taken while sailing from Porto Bello to Kingston with a cargo of cattle;

- Spanish schooner Misericordia taken while sailing from Old Spain to St. Jago with a cargo of dry goods;

- Two privateer barges; and

- French sloop Hazard, which was in ballast and which Lark destroyed.

- French schooner of unknown name with a cargo of cattle;

- Danish schooner Venus, of 35 tons with a cargo of coffee; and

- American schooner Edward and Edmond, of 80 tons and laden with cocoa.

Lark's next action occurred on 13 September 1801. With Lieutenant James Johnstone as acting captain, Lark chased a Spanish privateer schooner along the coast of Cuba until evening, when the schooner took refuge within the Portillo Reefs. Johnstone sent his yawl and cutter, each with sixteen men, including officers, to capture her. The privateer, which was armed with a long 8-pounder and two 4-pounders, opened fire on the boarding party. Still, the British prevailed, though they lost one man killed and a midshipman and 12 sailors wounded. The Spanish lost 21 dead, including their captain Joseph Callie, and six wounded; Lark took the remainder of the 45 man crew prisoner. The privateer was the Esperanza out of Santiago, and in the previous month she had taken the British sloop Eliza and the brig Betsey.

In April 1802 Edward Pelham Brenton took command. In July James Tippet may have been appointed to command, but on 4 July Lark left Jamaica for England. On 15 August, two days before she reached Plymouth, Lark encountered the brig Jane. Jane had apparently run out of food and water so Brenton provided her with some. After reaching Plymouth, Lark sailed the next day to Woolwich to be paid off.

Scale: 1:48. Plan showing the quarterdeck and forecastle, inboard profile, and upper deck for Hornet (1794), Cormorant (1794), Favourite (1794), Lynx (1794), Hazard (1794), Lark (1794), and Stork (1796), all 16-gun Ship Sloops. The plan was later altered in 1805 and used to build Hyacinth (1806), Herald (1806), Sabrina (1806), Cherub (1806), Minstrel (1807), Blossom (1806), Favourite (1806), Sapphire (1806), Wanderer (1806), Partridge (1809), Tweed (1807), Egeria (1807), Ranger (1807), Anacreon (1813), and Acorn (1807), Rosamond (1807), Fawn (1807), Myrtle (1807), Racoon (1808), and North Star (1810) all modified Cormorant class 16-gun Ship Sloops. The plan was altered again in 1808 while building Hesper (1809). The design for this class is 'similar to the French Ship Amazon' - the French Amazon (captured 1745).

Napoleonic Wars

On 31 May 1803 Lark was under the command of John Tower when she captured the French ship Marianne. On 11 April 1804 there was an announcement that when Lark next arrived at Deal that the prize agents would disburse a distribution of £5000 in prize money to those of her captain and crew who had participated in the capture. There was a second disbursement of £1759 in 1804. Lark also shared part of the proceeds of the capture with the English privateers Star and Polecat.

In May 1804 Lark was under the command of Fredrick Langford who in January 1805 took Lark from Portsmouth, headed for West Africa. In late January or early February he found a Spanish merchant vessel at anchor off the Bay of Senegal and captured her. She was the schooner Camerara, with two guns, though she was pierced for 16, and was carrying a cargo of wine. The Camerara was formerly French and had been a successful privateer at Cayenne under the ownership of Victor Hughes. The Governor of Senegal had intended to present her to her former captain, Victor Hughes, with the aim of using her to harass British trade on this part of the coast of Africa.

On 29 May 1805 Lark was in company with Squirrel off the coast of Guinea when they captured the French merchant brigantine Cecile.

Towards the end of 1806, Lark was escorting six merchantmen from Gorée when by the Savage Islands she came upon a French squadron consisting of five sail of the line, three frigates, a razée and two brig-corvettes. The convoy dispersed and Lark was able to escape and made her way to Cadiz to alert the British fleet there. Lark reached Cadiz on 26 November, and Rear Admiral Sir John Thomas Duckworth immediately took his squadron to try to find the French. The French squadron, under Contre-Admiral Allemand, was part of a French break-out from Brest.

Lark went on to Portsmouth. She then left Portsmouth under the command of Commander Robert Nicholas, bound for the West Indies. On the way, on 19 January 1807, she set off in pursuit of a Spanish schooner. Unfortunately, the schooner was carrying so much sail that a squall capsized her; Lark could not reach the spot where she went down before the schooner's entire crew had already drowned.

Later that January, on the 27th, and after a 14-hour pursuit, Lark captured two Spanish guarda costa (coast guard) vessels sailing from Cartagena to Portobelo. The two vessels were the Postillon (one long 12-pounder gun, two six-pounders, and 76 men), and the Carmen (one 12-pounder, four six pounders, and 72 men).

On 4 February Lark was still in company with the two guarda costas when they encountered two gunboats and an armed schooner escorting a Spanish convoy of several small market boats. Lark was able to drive the vessels of the convoy ashore, but the escorts took refuge under the guns of a 4-gun battery in a creek in Bahia Cispata, Colombia. Lark silenced the battery. Nicholas then took his entire crew, less the 20 men he left to guard the two guarda costas, and put them in boats with the aim of capturing the gunboats and the armed schooner. The Spanish gunboats rowed towards the British boats but then retreated as the British drew nearer. Nicholas and three of his men then were wounded while they were capturing the rearmost vessel, a gun boat with one 24-pounder and two 6-pounder guns. Later, Lark had three more men wounded in the continuing action. Nicholas then attempted to pursue the remaining Spanish vessels up a creek but while he was trying to do so, the pilot ran Postillon and Carmen ashore. This forced Nicholas to order their prize crews to burn them, which they did. Postillion blew up and Carmen was solidly aflame when the British last saw her.

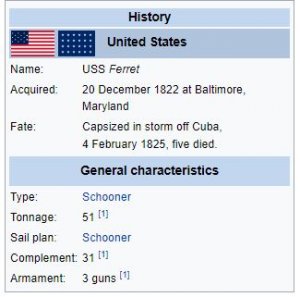

On 23 August, Lark, in the company of the Cruizer class brig sloop HMS Ferret, captured the French privateer schooner Mosquito, out of Santo Domingo. She had eight guns and a crew of 58 men.

In 1807, Nicholas became lieutenant governor of Curaçao shortly after the British captured it. When he left, the merchants there gave him a silver plate in appreciation for his efforts in protection of their trade.

In the summer of 1809, Lark participated in the blockade of San Domingo until the city fell on 11 July to Spanish forces and the British under Hugh Lyle Carmichael. The blockading squadron, under Captain William Pryce Cumby in the 64-gun third rate Polyphemus, also included Aurora, Tweed, Sparrow, Thrush, Griffon, Moselle, and Fleur de la Mer. Payment of prize money occurred in January 1826 and October 1832.

Loss

Unfortunately, on 3 August 1809, Lark foundered in a gale off Cape Causada (Point Palenqua), San Domingo. She was at anchor when the gale struck. She set sail at daybreak to get out to sea but while she was shortening sail a squall struck that turned her on her side. At that point a heavy sea struck her and she filled rapidly with water. She sank within 15 minutes, taking most of her crew with her. Some of her crew survived by hanging on to floating wreckage. However, by evening, when the Cruizer-class brig-sloop Moselle arrived, Commander Nicholas and all but three men of her crew of 120 were dead. Moselle then rescued the three survivors. Nicholas had just been promoted to post-captain with orders to command Garland.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Lark_(1794)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cormorant-class_ship-sloop

http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collec...el-324976;browseBy=vessel;vesselFacetLetter=L

https://threedecks.org/index.php?display_type=show_ship&id=5035

Line

Line

enbrouck

enbrouck