Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

6 December 1875 - SS Deutschland, an iron passenger steamship of the Norddeutscher Lloyd line, wrecked

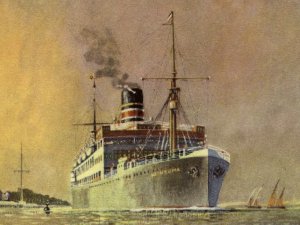

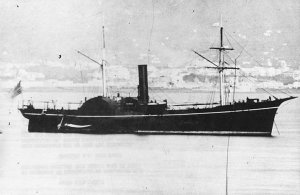

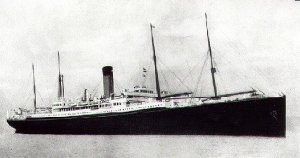

Deutschland was an iron passenger steamship of the Norddeutscher Lloyd line, built by Caird & Company of Greenock, Scotland in 1866.

History

Deutschland was built as an emigrant passenger ship. She entered service on 7 October 1866 and arrived at New York on her maiden voyage on 28 October.

Loss

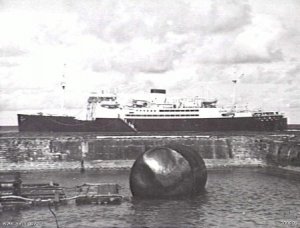

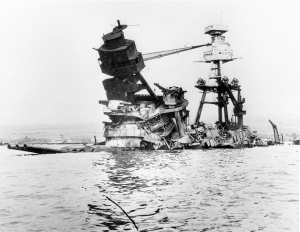

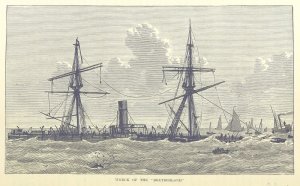

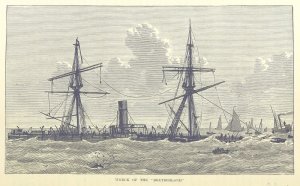

The wreck of the Deutschland

The Deutschland sailed from Bremerhaven on 4 December 1875, commanded by Captain Eduard Brickenstein, with 123 emigrants bound for New York via Southampton. Weather conditions were very bad with heavy snowstorms, and the ship had no clear idea of her position until, at 05:00 on 6 December, she ran aground in a blizzard on the Kentish Knock, a shoal 23 mi (37 km) off Harwich and 22 mi (35 km) from Margate, 3 mi (4.8 km) from the Kentish Knock lightvessel, and out of sight from shore. At the time she was 30 mi (48 km) from where Captain Brickenstein estimated she was.

Shortly before grounding, an attempt was made to go astern but this failed when the stress fractured the ship's propeller. Driven onto the sandbank, the vessel began to take on water and as the tide rose she failed to lift off the shoal as had been expected. When the sea began to break over her, and the wind rose to gale force, the order was given to abandon ship, causing some panic. One boat was launched, but was swamped, while a second boat, with the quartermaster, a sailor and a passenger aboard, went adrift and eventually reached shore on the Isle of Sheppey the next day with only the quartermaster left alive. The remaining boats were later washed away or destroyed by the stormy seas.

Distress rockets were seen on the morning of 6 December by the Sunk lightship, which tried through the day to attract the attention of passing shipping, without success. Later, rockets from that light vessel were seen by another, whose own rockets were seen at Harwich in the evening, though neither the nature nor location of the casualty were known. The paddle tug Liverpool was dispatched at daylight on 7 December, reaching the Deutschland via the sequence of light vessels, and embarked all 173 still alive on the wreck.

Aftermath

Soon after the news of the disaster had broken, the wreck was raided by men from the nearby coastal towns, particularly Harwich and Ramsgate. An artist from the Illustrated London produced an illustration of the scene which depicted the wreckers as resembling a flock of vultures. The Times also described the scene, saying that corpses had been ransacked, and their jewellery stolen.

produced an illustration of the scene which depicted the wreckers as resembling a flock of vultures. The Times also described the scene, saying that corpses had been ransacked, and their jewellery stolen.

While there were some far-fetched suggestions that the Deutschland had been deliberately wrecked, there were well-founded allegations of deliberate delay in coming to the ship's assistance, as well as some of negligence. The Times published a leader which said that the Deutschland's grounding had been known for 15 hours of the 30 hours it took for the tug Liverpool to come to her aid, and Captain Carrington, her master, was criticized for his slowness in acting.

The Board of Trade enquiry into the accident opened at Poplar, London, on 20 December. It was not usual to hold such an enquiry in the case of a foreign registered vessel being wrecked outside the three-mile limit, and it may have been done to respond to the criticisms which had been raised regarding the delay in coming to the ship's aid. Charles Butt QC, who had been briefed by the German government, stated that it was surprising that "a large steamer with upwards of 200 persons aboard should have lain on a dangerous sand close to the English coast for thirty hours before any assistance came to her".

The enquiry eventually exonerated everyone of any blame except Captain Brickenstein, who, it was decided, had "let his vessel get ahead in its reckoning" and "shown a very great want of care and judgement". Brickenstein asked the German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck for an official German investigation, but this was ruled out.

31 Stunden Hölle - Die letzte Fahrt der Deutschland [DOKU][HD]

Legacy

Among the victims of the shipwreck were five Franciscan Sisters of the Sacred Hearts from Salzkotten, Westphalia, in the Kingdom of Prussia, who had been emigrating to the United States. This was both to escape the anti-Catholic Falk Laws and to answer the need for nursing care in the German population of St. Louis, Missouri. Their deaths inspired Jesuit poet Gerard Manley Hopkins to compose the poem The Wreck of the Deutschland. Four of the five Sisters were buried in St. Patrick's Cemetery in Leytonstone, London, (a fifth whose body was never found is recorded on the memorial) and their deaths are commemorated every year in a memorial service held on 6 December in Wheaton, Illinois, by the Franciscan Sisters of their religious congregation now headquartered there.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SS_Deutschland_(1866)

6 December 1875 - SS Deutschland, an iron passenger steamship of the Norddeutscher Lloyd line, wrecked

Deutschland was an iron passenger steamship of the Norddeutscher Lloyd line, built by Caird & Company of Greenock, Scotland in 1866.

History

Deutschland was built as an emigrant passenger ship. She entered service on 7 October 1866 and arrived at New York on her maiden voyage on 28 October.

Loss

The wreck of the Deutschland

The Deutschland sailed from Bremerhaven on 4 December 1875, commanded by Captain Eduard Brickenstein, with 123 emigrants bound for New York via Southampton. Weather conditions were very bad with heavy snowstorms, and the ship had no clear idea of her position until, at 05:00 on 6 December, she ran aground in a blizzard on the Kentish Knock, a shoal 23 mi (37 km) off Harwich and 22 mi (35 km) from Margate, 3 mi (4.8 km) from the Kentish Knock lightvessel, and out of sight from shore. At the time she was 30 mi (48 km) from where Captain Brickenstein estimated she was.

Shortly before grounding, an attempt was made to go astern but this failed when the stress fractured the ship's propeller. Driven onto the sandbank, the vessel began to take on water and as the tide rose she failed to lift off the shoal as had been expected. When the sea began to break over her, and the wind rose to gale force, the order was given to abandon ship, causing some panic. One boat was launched, but was swamped, while a second boat, with the quartermaster, a sailor and a passenger aboard, went adrift and eventually reached shore on the Isle of Sheppey the next day with only the quartermaster left alive. The remaining boats were later washed away or destroyed by the stormy seas.

Distress rockets were seen on the morning of 6 December by the Sunk lightship, which tried through the day to attract the attention of passing shipping, without success. Later, rockets from that light vessel were seen by another, whose own rockets were seen at Harwich in the evening, though neither the nature nor location of the casualty were known. The paddle tug Liverpool was dispatched at daylight on 7 December, reaching the Deutschland via the sequence of light vessels, and embarked all 173 still alive on the wreck.

Aftermath

Soon after the news of the disaster had broken, the wreck was raided by men from the nearby coastal towns, particularly Harwich and Ramsgate. An artist from the Illustrated London

produced an illustration of the scene which depicted the wreckers as resembling a flock of vultures. The Times also described the scene, saying that corpses had been ransacked, and their jewellery stolen.

produced an illustration of the scene which depicted the wreckers as resembling a flock of vultures. The Times also described the scene, saying that corpses had been ransacked, and their jewellery stolen.While there were some far-fetched suggestions that the Deutschland had been deliberately wrecked, there were well-founded allegations of deliberate delay in coming to the ship's assistance, as well as some of negligence. The Times published a leader which said that the Deutschland's grounding had been known for 15 hours of the 30 hours it took for the tug Liverpool to come to her aid, and Captain Carrington, her master, was criticized for his slowness in acting.

The Board of Trade enquiry into the accident opened at Poplar, London, on 20 December. It was not usual to hold such an enquiry in the case of a foreign registered vessel being wrecked outside the three-mile limit, and it may have been done to respond to the criticisms which had been raised regarding the delay in coming to the ship's aid. Charles Butt QC, who had been briefed by the German government, stated that it was surprising that "a large steamer with upwards of 200 persons aboard should have lain on a dangerous sand close to the English coast for thirty hours before any assistance came to her".

The enquiry eventually exonerated everyone of any blame except Captain Brickenstein, who, it was decided, had "let his vessel get ahead in its reckoning" and "shown a very great want of care and judgement". Brickenstein asked the German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck for an official German investigation, but this was ruled out.

Legacy

Among the victims of the shipwreck were five Franciscan Sisters of the Sacred Hearts from Salzkotten, Westphalia, in the Kingdom of Prussia, who had been emigrating to the United States. This was both to escape the anti-Catholic Falk Laws and to answer the need for nursing care in the German population of St. Louis, Missouri. Their deaths inspired Jesuit poet Gerard Manley Hopkins to compose the poem The Wreck of the Deutschland. Four of the five Sisters were buried in St. Patrick's Cemetery in Leytonstone, London, (a fifth whose body was never found is recorded on the memorial) and their deaths are commemorated every year in a memorial service held on 6 December in Wheaton, Illinois, by the Franciscan Sisters of their religious congregation now headquartered there.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SS_Deutschland_(1866)

was a maritime disaster in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

was a maritime disaster in Halifax, Nova Scotia.