Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

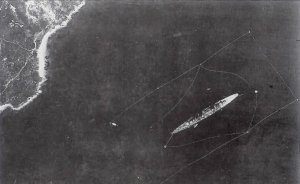

10 April 1943 - italian Trento-class heavy cruisers Trieste, while moored in La Maddalena, Sardinia, was bombed and sunk by American heavy bombers

Trieste was the second of two Trento-class heavy cruisers built for the Italian Regia Marina (Royal Navy). The ship was laid down in June 1925, was launched in October 1926, and was commissioned in December 1928. Trieste was very lightly armored, with only a 70 mm (2.8 in) thick armored belt, though she possessed a high speed and heavy armament of eight 203 mm (8.0 in) guns. Though nominally built under the restrictions of the Washington Naval Treaty, the two cruisers significantly exceeded the displacement limits imposed by the treaty. The ship spent the 1930s conducting training cruises in the Mediterranean Sea, participating in naval reviews held for foreign dignitaries, and serving as the flagship of the Cruiser Division. She also helped transport Italian volunteer troops that had been sent to Spain to fight in the Spanish Civil War return to Italy in 1938.

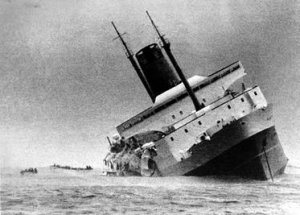

The ship saw extensive action during World War II, including the battles of Cape Spartivento and Cape Matapan in November 1940 and March 1941, respectively. Trieste was also employed to escort convoys to supply Italian forces in North Africa; during one of these operations in November 1941, she was torpedoed by a British submarine. On 10 April 1943, while the ship was moored in La Maddalena, Sardinia, she was bombed and sunk by American heavy bombers. Her superstructure was cut away and she was refloated in 1950; the Spanish Navy purchased the hull in 1952, with plans to convert the vessel into a light aircraft carrier, though the plan came to nothing due to the growing costs of the project. She was ultimately broken up by 1959.

Design

Main article: Trento-class cruiser

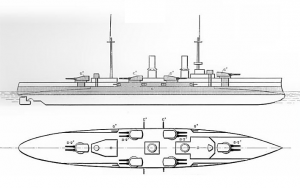

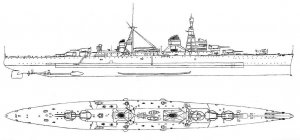

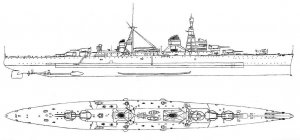

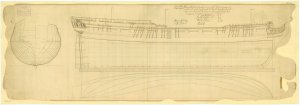

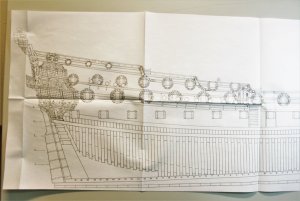

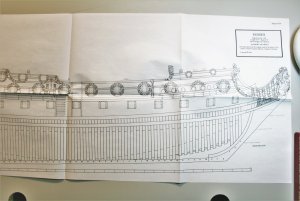

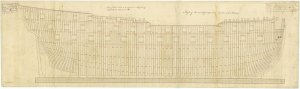

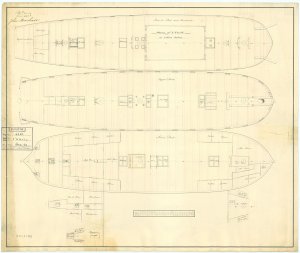

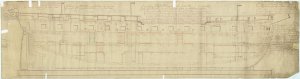

Line-drawing of the Trento class

Trieste was 196.96 meters (646 ft 2 in) long overall, with a beam of 20.6 m (67 ft 7 in) and a draft of 6.8 m (22 ft 4 in). She displaced 13,326 long tons (13,540 t) at full load, though her displacement was nominally within the 10,000-long-ton (10,000 t) restriction set in place by the Washington Naval Treaty. She had a crew of 723 officers and enlisted men, though during the war this increased to 781. Her power plant consisted of four Parsons steam turbines powered by twelve oil-fired Yarrow boilers, which were trunked into two funnels amidships. Her engines were rated at 150,000 shaft horsepower (110,000 kW) for a top speed of 36 knots (67 km/h; 41 mph), but on sea trials only reached 35.65 knots (66.02 km/h; 41.03 mph). That speed could only be reached on a very light displacement, and in service, her practical top speed was only 31 knots (57 km/h; 36 mph). The ship had a cruising range of 4,160 nautical miles (7,700 km; 4,790 mi) at a speed of 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph)

She was protected with an armored belt that was 70 mm (2.8 in) thick amidships with armored bulkheads 40 to 60 mm (1.6 to 2.4 in) thick on either end. Her armor deck was 50 mm (2.0 in) thick in the central portion of the ship and reduced to 20 mm (0.79 in) at either end. The gun turrets had 100 mm (3.9 in) thick plating on the faces and the supporting barbettes they sat in were 60 to 70 mm (2.4 to 2.8 in) thick. The main conning tower had 100 mm thick sides.

Trieste was armed with a main battery of eight 203 mm (8.0 in) Mod 24 50-caliber guns in four gun turrets. The turrets were arranged in superfiring pairs forward and aft. Anti-aircraft defense was provided by a battery of sixteen 100 mm (4 in) 47-cal. guns in twin mounts, four Vickers-Terni 40 mm/39 guns in single mounts and four 12.7 mm (0.50 in) guns. In addition to the gun armament, she carried eight 533 mm (21.0 in) torpedo tubes in four deck mounted twin launchers. She carried a pair of IMAM Ro.43 seaplanes for aerial reconnaissance; the hangar was located in under the forecastle and a fixed catapult was mounted on the centerline at the bow.

Trieste's secondary battery was revised several times during her career. The 100 mm guns were replaced with newer Mod 31 versions of the same caliber. In 1937–1938, the two aft-most 100 mm guns were removed, along with all four 12.7 mm machine guns; eight 37 mm (1.5 in) 54-cal. Breda M1932 guns and eight 13.2 mm (0.52 in) Breda M1931 machine guns, all in twin mounts, were installed in their place. In 1943, the ship received eight 20 mm (0.79 in) 65-cal. Breda M1940 guns in single mounts.

Service history

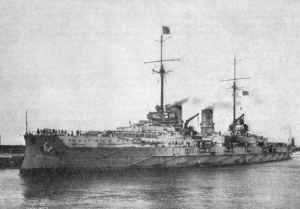

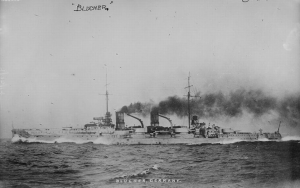

Trieste early in her career

Trieste had her keel laid at the Stabilimento Tecnico Triestino shipyard in her namesake city on 22 June 1925. The completed hull was launched on 24 October 1926, a year before her sister Trento. After fitting-out work was completed, the ship was commissioned into the Italian fleet on 21 December 1928. On 16 May 1929 she joined Trento in the newly created Cruiser Division for a cruise in the northern Mediterranean Sea that lasted until 4 June. On 1 October, Trieste became the flagship of the 1st Squadron. In mid-1931, she entered the shipyard in La Spezia for an overhaul that included the replacement of her tripod foremast with a more stable five-legged version. On 6 and 7 July 1933, Trieste, Trento, and the four Zara-class cruisers held a naval review for the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini in the Gulf of Naples. On 2 December 1933, Trieste, Trento, and the heavy cruiser Bolzano formed the 2nd Division of the 1st Squadron. The unit was renamed the 3rd Division in July 1934.

On 18 June 1935, Trieste temporarily relieved Trento as the divisional flagship. Mussolini took a short tour of Italian Libya from 10 to 12 March 1937, and Trieste was among the vessels to escort him. On 7 June, she took part in a major naval review held during the visit of German Field Marshal Werner von Blomberg. The ship became the 2nd Squadron flagship on 15 February 1938. On 5 May, another naval review was held in the Gulf of Naples, this time for the state visit of German dictator Adolf Hitler. On 12 October 1938, Trieste steamed out of Messina with the 10th Destroyer Squadron, bound for Cadiz, Spain. There, they met four Italian merchant ships on 15 October, which embarked 10,000 members of the Corpo Truppe Volontarie (Corps of Volunteer Troops) that had been sent to support General Francisco Franco's Nationalist forces during the Spanish Civil War. The convoy left Cadiz on 16 October and arrived back in Naples on the 20th. On 17 May 1939, Trieste took part in another fleet review, this one for Prince Paul of Yugoslavia during his visit to Italy. From 5 to 19 June, Trieste joined the rest of the fleet in Livorno for the first celebration of Navy Day on 10 June. From October to December, the ship underwent a major refit, which included modifications to her armament and the installation of funnel caps.

World War II

On 10 June 1940, Italy declared war on Britain and France, formally entering World War II. The heavy cruiser Pola replaced Trieste as the squadron flagship, which in turn became the flagship of the 3rd Division, which also included Trento and Bolzano. These four cruisers deployed north of Sicily to patrol for Allied vessels on Italy's first day of the war. On 31 August, the 3rd Division sortied to intercept the British convoy from Alexandria to Malta in Operation Hats, though the Italian fleet broke off the operation without encountering the merchant ships. Trieste arrived back in Taranto on 2 September. She was present there on the night of 11–12 November, when the British raided the port, and she emerged undamaged.

Trieste sortied with the fleet on 26 November in an attempt to intercept another convoy to Malta. The following morning, a reconnaissance floatplane from Bolzano located the British squadron. Shortly after 12:00, Italian reconnaissance reports informed the Italian fleet commander, Vice Admiral Inigo Campioni of the strength of the British fleet, and so he ordered his ships to disengage. By this time, Trieste and the other heavy cruisers had already begun engaging their British counterparts in the Battle of Cape Spartivento, and had scored two hits on the cruiser HMS Berwick, the second of which is credited to either Trieste or Trento. The battlecruiser HMS Renown intervened, and quickly straddled Trieste twice, though she inflicted only splinter damage. This forced Campioni to commit the battleship Vittorio Veneto, which in turn forced the British cruisers to break off the action, allowing both sides to disengage.

On 9 February 1941, Trieste sortied with the rest of the 2nd Squadron to search for Force H after the latter had shelled Genoa; the Italians returned to port without success. On 12–13 March, Trieste escorted a fast convoy to North Africa.

Battle of Cape Matapan

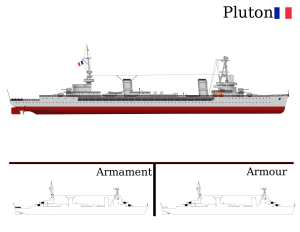

Map showing the movements of the Italian and British fleets

Main article: Battle of Cape Matapan

On 27 March, the division sortied with the rest of the fleet for a major sweep toward the island of Crete. During the operation, Trieste flew the flag of Rear Admiral Luigi Sansonetti. At 06:55 on the 28th, an IMAM Ro.43 floatplane launched by Vittorio Veneto located a British cruiser squadron, and by 07:55, Trento and the 3rd Division had come within visual range. Seventeen minutes later, the Italian cruisers opened fire from a range of 24,000 yd (22,000 m), initiating the first phase of the Battle of Cape Matapan; in the span of the next forty minutes, Trieste fired a total of 132 armor-piercing shells, though trouble with her rangefinders and the extreme range of the action prevented her from scoring any significant hits.

At 08:55, the Italian fleet commander, Vice Admiral Angelo Iachino instructed Sansonetti to break off the action with the British cruisers and turn northwest, to lure the British vessels into range for Vittorio Veneto. By about 11:00, Vittorio Veneto had closed the distance enough to open fire, prompting Sansonetti to turn his three cruisers back to join the fight. The 6-inch-gun-armed British cruisers were outmatched both by the Italian heavy cruisers and Vittorio Veneto, and they quickly reversed course. While the two sides were still maneuvering, a group of British torpedo bombers from Crete arrived and unsuccessfully attacked Trieste and the rest of her division shortly after 12:00. Further attacks from the aircraft carrier HMS Formidable convinced Iachino to break off the action and withdraw at 12:20.

Later in the day, Vittorio Veneto and Pola were torpedoed by British aircraft, the latter left immobilized. Trieste, Trento, and Bolzano were also attacked by aircraft, but they escaped without damage. Trieste reached Taranto in company with the damaged Vittorio Veneto at 15:30 the following day. in the meantime, Pola and two other Zara-class cruisers were destroyed in the night action with British battleships late on the 28th.

Convoy operations

From 24 to 30 April, Trieste and Bolzano escorted a convoy to North Africa. A combination of heavy seas and the presence of British warships forced the convoy to shelter in Palermo, Messina, and Augusta in Sicily before being able to make the crossing to Tripoli. A month later, the two cruisers covered another convoy; for the return leg of the voyage, the ships joined a second convoy also returning to Italy. Another convoy made the crossing on 8–9 June, again escorted by Trieste and Bolzano, along with the destroyers Corazziere, Ascari, and Lanciere. Trieste and the heavy cruiser Gorizia and the vessels of the 12th Destroyer Squadron covered four ocean liners that had been converted into troopships on 25 June; heavy British air attacks that night forced the convoy to return to Taranto. A second attempt was made on 27 June, and the ships successfully reached Tripoli on the morning of the 29th. Heavy air attacks targeted the ships while they were unloading the following day, but the ships were able to complete the task, depart that day, and reach Taranto on 1 July.

From 16 to 20 July, Trieste, Bolzano, Ascari, Corazziere, and the destroyer Carabiniere covered another fast convoy to Tripoli. On 22 August, Trieste sortied with other elements of the Italian fleet to try to locate Force H; they returned to port four days later empty handed. In late September, the British sent another convoy to reinforce Malta, codenamed Operation Halberd; the Italian fleet sortied on 26 September to try to intercept it, but broke off the operation upon discovering the strength of the British escort force. Trieste took part in the Duisberg convoy on 8–9 November along with Trento, the two ships serving as the convoy's covering force. The convoy was attacked by British warships in the early hours of 9 November, though the covering force failed to intervene and the convoy was destroyed.

Trieste escorted another convoy to Libya on 21 November in company with the light cruiser Duca degli Abruzzi. Late that evening, the convoy came under a combined submarine and aircraft attack; at 23:12, Trieste was torpedoed by the submarine HMS Utmost, and a torpedo bomber hit Duca degli Abruzzi shortly thereafter. The two damaged vessels were escorted back to Messina by the cruiser Giuseppe Garibaldi and the destroyer Bersagliere, arriving at around 08:00 the next morning. After repairs were completed, Trieste joined Bolzano and Gorizia—the only other surviving heavy cruisers in the fleet—in the reorganized 3rd Division. The ships sortied with eight destroyers on 12 August 1942 to try to intercept a British convoy; while on the operation, Bolzano and one of the destroyers were torpedoed by a British submarine, forcing the cancellation of the mission.

Fate

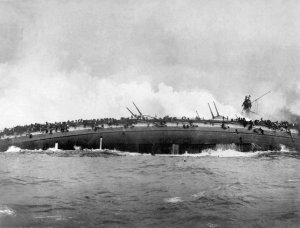

On 10 April 1943, while moored in La Maddalena, Sardinia, Trieste came under attack from B-24 Liberator heavy bombers from the United States Army Air Forces. She received several hits at 13:45, and at 16:13 she capsized to starboard and sank in the shallow water. Casualties were relatively light, with 66 men killed or missing—of those, three were officers, eight were non-commissioned officers, and fifty-five were enlisted sailors—and 66 wounded—eight NCOs and fifty-eight sailors. The ship remained on the naval register until 18 October 1946, when she was formally stricken. Salvage operations began in 1950, starting with the removal of the ship's superstructure. The hull was then made watertight, was refloated, still capsized, and was towed to La Spezia. There, the ship was righted, and upon inspection, the shipyard workers discovered that fuel oil that had leaked into the engine rooms had preserved the machinery. The Spanish Navy purchased the hull and towed it to Cartagena and then to Ferrol in 1952 to convert Trieste into a light aircraft carrier. The cost of the project proved to be prohibitive, and in 1956 the Spanish Navy sold the vessel for scrap; the ship was broken up by 1959.

en.wikipedia.org

http://conlapelleappesaaunchiodo.blogspot.com/2014/07/trieste.html

en.wikipedia.org

http://conlapelleappesaaunchiodo.blogspot.com/2014/07/trieste.html

10 April 1943 - italian Trento-class heavy cruisers Trieste, while moored in La Maddalena, Sardinia, was bombed and sunk by American heavy bombers

Trieste was the second of two Trento-class heavy cruisers built for the Italian Regia Marina (Royal Navy). The ship was laid down in June 1925, was launched in October 1926, and was commissioned in December 1928. Trieste was very lightly armored, with only a 70 mm (2.8 in) thick armored belt, though she possessed a high speed and heavy armament of eight 203 mm (8.0 in) guns. Though nominally built under the restrictions of the Washington Naval Treaty, the two cruisers significantly exceeded the displacement limits imposed by the treaty. The ship spent the 1930s conducting training cruises in the Mediterranean Sea, participating in naval reviews held for foreign dignitaries, and serving as the flagship of the Cruiser Division. She also helped transport Italian volunteer troops that had been sent to Spain to fight in the Spanish Civil War return to Italy in 1938.

The ship saw extensive action during World War II, including the battles of Cape Spartivento and Cape Matapan in November 1940 and March 1941, respectively. Trieste was also employed to escort convoys to supply Italian forces in North Africa; during one of these operations in November 1941, she was torpedoed by a British submarine. On 10 April 1943, while the ship was moored in La Maddalena, Sardinia, she was bombed and sunk by American heavy bombers. Her superstructure was cut away and she was refloated in 1950; the Spanish Navy purchased the hull in 1952, with plans to convert the vessel into a light aircraft carrier, though the plan came to nothing due to the growing costs of the project. She was ultimately broken up by 1959.

Design

Main article: Trento-class cruiser

Line-drawing of the Trento class

Trieste was 196.96 meters (646 ft 2 in) long overall, with a beam of 20.6 m (67 ft 7 in) and a draft of 6.8 m (22 ft 4 in). She displaced 13,326 long tons (13,540 t) at full load, though her displacement was nominally within the 10,000-long-ton (10,000 t) restriction set in place by the Washington Naval Treaty. She had a crew of 723 officers and enlisted men, though during the war this increased to 781. Her power plant consisted of four Parsons steam turbines powered by twelve oil-fired Yarrow boilers, which were trunked into two funnels amidships. Her engines were rated at 150,000 shaft horsepower (110,000 kW) for a top speed of 36 knots (67 km/h; 41 mph), but on sea trials only reached 35.65 knots (66.02 km/h; 41.03 mph). That speed could only be reached on a very light displacement, and in service, her practical top speed was only 31 knots (57 km/h; 36 mph). The ship had a cruising range of 4,160 nautical miles (7,700 km; 4,790 mi) at a speed of 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph)

She was protected with an armored belt that was 70 mm (2.8 in) thick amidships with armored bulkheads 40 to 60 mm (1.6 to 2.4 in) thick on either end. Her armor deck was 50 mm (2.0 in) thick in the central portion of the ship and reduced to 20 mm (0.79 in) at either end. The gun turrets had 100 mm (3.9 in) thick plating on the faces and the supporting barbettes they sat in were 60 to 70 mm (2.4 to 2.8 in) thick. The main conning tower had 100 mm thick sides.

Trieste was armed with a main battery of eight 203 mm (8.0 in) Mod 24 50-caliber guns in four gun turrets. The turrets were arranged in superfiring pairs forward and aft. Anti-aircraft defense was provided by a battery of sixteen 100 mm (4 in) 47-cal. guns in twin mounts, four Vickers-Terni 40 mm/39 guns in single mounts and four 12.7 mm (0.50 in) guns. In addition to the gun armament, she carried eight 533 mm (21.0 in) torpedo tubes in four deck mounted twin launchers. She carried a pair of IMAM Ro.43 seaplanes for aerial reconnaissance; the hangar was located in under the forecastle and a fixed catapult was mounted on the centerline at the bow.

Trieste's secondary battery was revised several times during her career. The 100 mm guns were replaced with newer Mod 31 versions of the same caliber. In 1937–1938, the two aft-most 100 mm guns were removed, along with all four 12.7 mm machine guns; eight 37 mm (1.5 in) 54-cal. Breda M1932 guns and eight 13.2 mm (0.52 in) Breda M1931 machine guns, all in twin mounts, were installed in their place. In 1943, the ship received eight 20 mm (0.79 in) 65-cal. Breda M1940 guns in single mounts.

Service history

Trieste early in her career

Trieste had her keel laid at the Stabilimento Tecnico Triestino shipyard in her namesake city on 22 June 1925. The completed hull was launched on 24 October 1926, a year before her sister Trento. After fitting-out work was completed, the ship was commissioned into the Italian fleet on 21 December 1928. On 16 May 1929 she joined Trento in the newly created Cruiser Division for a cruise in the northern Mediterranean Sea that lasted until 4 June. On 1 October, Trieste became the flagship of the 1st Squadron. In mid-1931, she entered the shipyard in La Spezia for an overhaul that included the replacement of her tripod foremast with a more stable five-legged version. On 6 and 7 July 1933, Trieste, Trento, and the four Zara-class cruisers held a naval review for the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini in the Gulf of Naples. On 2 December 1933, Trieste, Trento, and the heavy cruiser Bolzano formed the 2nd Division of the 1st Squadron. The unit was renamed the 3rd Division in July 1934.

On 18 June 1935, Trieste temporarily relieved Trento as the divisional flagship. Mussolini took a short tour of Italian Libya from 10 to 12 March 1937, and Trieste was among the vessels to escort him. On 7 June, she took part in a major naval review held during the visit of German Field Marshal Werner von Blomberg. The ship became the 2nd Squadron flagship on 15 February 1938. On 5 May, another naval review was held in the Gulf of Naples, this time for the state visit of German dictator Adolf Hitler. On 12 October 1938, Trieste steamed out of Messina with the 10th Destroyer Squadron, bound for Cadiz, Spain. There, they met four Italian merchant ships on 15 October, which embarked 10,000 members of the Corpo Truppe Volontarie (Corps of Volunteer Troops) that had been sent to support General Francisco Franco's Nationalist forces during the Spanish Civil War. The convoy left Cadiz on 16 October and arrived back in Naples on the 20th. On 17 May 1939, Trieste took part in another fleet review, this one for Prince Paul of Yugoslavia during his visit to Italy. From 5 to 19 June, Trieste joined the rest of the fleet in Livorno for the first celebration of Navy Day on 10 June. From October to December, the ship underwent a major refit, which included modifications to her armament and the installation of funnel caps.

World War II

On 10 June 1940, Italy declared war on Britain and France, formally entering World War II. The heavy cruiser Pola replaced Trieste as the squadron flagship, which in turn became the flagship of the 3rd Division, which also included Trento and Bolzano. These four cruisers deployed north of Sicily to patrol for Allied vessels on Italy's first day of the war. On 31 August, the 3rd Division sortied to intercept the British convoy from Alexandria to Malta in Operation Hats, though the Italian fleet broke off the operation without encountering the merchant ships. Trieste arrived back in Taranto on 2 September. She was present there on the night of 11–12 November, when the British raided the port, and she emerged undamaged.

Trieste sortied with the fleet on 26 November in an attempt to intercept another convoy to Malta. The following morning, a reconnaissance floatplane from Bolzano located the British squadron. Shortly after 12:00, Italian reconnaissance reports informed the Italian fleet commander, Vice Admiral Inigo Campioni of the strength of the British fleet, and so he ordered his ships to disengage. By this time, Trieste and the other heavy cruisers had already begun engaging their British counterparts in the Battle of Cape Spartivento, and had scored two hits on the cruiser HMS Berwick, the second of which is credited to either Trieste or Trento. The battlecruiser HMS Renown intervened, and quickly straddled Trieste twice, though she inflicted only splinter damage. This forced Campioni to commit the battleship Vittorio Veneto, which in turn forced the British cruisers to break off the action, allowing both sides to disengage.

On 9 February 1941, Trieste sortied with the rest of the 2nd Squadron to search for Force H after the latter had shelled Genoa; the Italians returned to port without success. On 12–13 March, Trieste escorted a fast convoy to North Africa.

Battle of Cape Matapan

Map showing the movements of the Italian and British fleets

Main article: Battle of Cape Matapan

On 27 March, the division sortied with the rest of the fleet for a major sweep toward the island of Crete. During the operation, Trieste flew the flag of Rear Admiral Luigi Sansonetti. At 06:55 on the 28th, an IMAM Ro.43 floatplane launched by Vittorio Veneto located a British cruiser squadron, and by 07:55, Trento and the 3rd Division had come within visual range. Seventeen minutes later, the Italian cruisers opened fire from a range of 24,000 yd (22,000 m), initiating the first phase of the Battle of Cape Matapan; in the span of the next forty minutes, Trieste fired a total of 132 armor-piercing shells, though trouble with her rangefinders and the extreme range of the action prevented her from scoring any significant hits.

At 08:55, the Italian fleet commander, Vice Admiral Angelo Iachino instructed Sansonetti to break off the action with the British cruisers and turn northwest, to lure the British vessels into range for Vittorio Veneto. By about 11:00, Vittorio Veneto had closed the distance enough to open fire, prompting Sansonetti to turn his three cruisers back to join the fight. The 6-inch-gun-armed British cruisers were outmatched both by the Italian heavy cruisers and Vittorio Veneto, and they quickly reversed course. While the two sides were still maneuvering, a group of British torpedo bombers from Crete arrived and unsuccessfully attacked Trieste and the rest of her division shortly after 12:00. Further attacks from the aircraft carrier HMS Formidable convinced Iachino to break off the action and withdraw at 12:20.

Later in the day, Vittorio Veneto and Pola were torpedoed by British aircraft, the latter left immobilized. Trieste, Trento, and Bolzano were also attacked by aircraft, but they escaped without damage. Trieste reached Taranto in company with the damaged Vittorio Veneto at 15:30 the following day. in the meantime, Pola and two other Zara-class cruisers were destroyed in the night action with British battleships late on the 28th.

Convoy operations

From 24 to 30 April, Trieste and Bolzano escorted a convoy to North Africa. A combination of heavy seas and the presence of British warships forced the convoy to shelter in Palermo, Messina, and Augusta in Sicily before being able to make the crossing to Tripoli. A month later, the two cruisers covered another convoy; for the return leg of the voyage, the ships joined a second convoy also returning to Italy. Another convoy made the crossing on 8–9 June, again escorted by Trieste and Bolzano, along with the destroyers Corazziere, Ascari, and Lanciere. Trieste and the heavy cruiser Gorizia and the vessels of the 12th Destroyer Squadron covered four ocean liners that had been converted into troopships on 25 June; heavy British air attacks that night forced the convoy to return to Taranto. A second attempt was made on 27 June, and the ships successfully reached Tripoli on the morning of the 29th. Heavy air attacks targeted the ships while they were unloading the following day, but the ships were able to complete the task, depart that day, and reach Taranto on 1 July.

From 16 to 20 July, Trieste, Bolzano, Ascari, Corazziere, and the destroyer Carabiniere covered another fast convoy to Tripoli. On 22 August, Trieste sortied with other elements of the Italian fleet to try to locate Force H; they returned to port four days later empty handed. In late September, the British sent another convoy to reinforce Malta, codenamed Operation Halberd; the Italian fleet sortied on 26 September to try to intercept it, but broke off the operation upon discovering the strength of the British escort force. Trieste took part in the Duisberg convoy on 8–9 November along with Trento, the two ships serving as the convoy's covering force. The convoy was attacked by British warships in the early hours of 9 November, though the covering force failed to intervene and the convoy was destroyed.

Trieste escorted another convoy to Libya on 21 November in company with the light cruiser Duca degli Abruzzi. Late that evening, the convoy came under a combined submarine and aircraft attack; at 23:12, Trieste was torpedoed by the submarine HMS Utmost, and a torpedo bomber hit Duca degli Abruzzi shortly thereafter. The two damaged vessels were escorted back to Messina by the cruiser Giuseppe Garibaldi and the destroyer Bersagliere, arriving at around 08:00 the next morning. After repairs were completed, Trieste joined Bolzano and Gorizia—the only other surviving heavy cruisers in the fleet—in the reorganized 3rd Division. The ships sortied with eight destroyers on 12 August 1942 to try to intercept a British convoy; while on the operation, Bolzano and one of the destroyers were torpedoed by a British submarine, forcing the cancellation of the mission.

Fate

On 10 April 1943, while moored in La Maddalena, Sardinia, Trieste came under attack from B-24 Liberator heavy bombers from the United States Army Air Forces. She received several hits at 13:45, and at 16:13 she capsized to starboard and sank in the shallow water. Casualties were relatively light, with 66 men killed or missing—of those, three were officers, eight were non-commissioned officers, and fifty-five were enlisted sailors—and 66 wounded—eight NCOs and fifty-eight sailors. The ship remained on the naval register until 18 October 1946, when she was formally stricken. Salvage operations began in 1950, starting with the removal of the ship's superstructure. The hull was then made watertight, was refloated, still capsized, and was towed to La Spezia. There, the ship was righted, and upon inspection, the shipyard workers discovered that fuel oil that had leaked into the engine rooms had preserved the machinery. The Spanish Navy purchased the hull and towed it to Cartagena and then to Ferrol in 1952 to convert Trieste into a light aircraft carrier. The cost of the project proved to be prohibitive, and in 1956 the Spanish Navy sold the vessel for scrap; the ship was broken up by 1959.

Italian cruiser Trieste - Wikipedia

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

, No. 37. —This bottle has been thrown overboard, to determine the current, by Mr. W. H. Hale, of H.M.S. Briton. Whoever finds it, is requested to give intelligence of the same, in writing, to Mr. Harrison, the editor of the Hampshire Telegraph, at Portsmouth. —H.M.S. Briton, Captain the Hon. W. Gordon, Gulf of Mexico, 2nd February, 1830, from Tampico to England, in lat. 27° 50', lon. 84° 40'. Tortugas S. 18°, E. 230 miles."

, No. 37. —This bottle has been thrown overboard, to determine the current, by Mr. W. H. Hale, of H.M.S. Briton. Whoever finds it, is requested to give intelligence of the same, in writing, to Mr. Harrison, the editor of the Hampshire Telegraph, at Portsmouth. —H.M.S. Briton, Captain the Hon. W. Gordon, Gulf of Mexico, 2nd February, 1830, from Tampico to England, in lat. 27° 50', lon. 84° 40'. Tortugas S. 18°, E. 230 miles."