Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

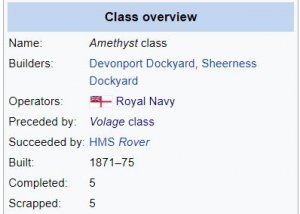

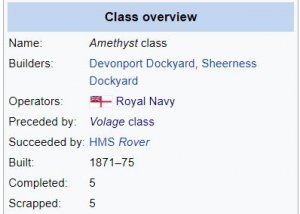

19 April 1873 – Launch of HMS Amethyst, the lead ship of the Amethyst-class corvettes built for the Royal Navy in the early 1870s.

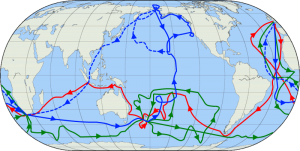

HMS Amethyst was the lead ship of the Amethyst-class corvettes built for the Royal Navy in the early 1870s. She participated in the Third Anglo-Ashanti War in 1873 before serving as the senior officer's ship for the South American side of the South Atlantic. The ship was transferred to the Pacific Station in 1875 and fought in the Battle of Pacocha against the rebellious Peruvian ironclad warship Huáscar two years later. This made her the only British wooden sailing ship ever to fight an armoured opponent. After a lengthy refit, Amethystagain served as the senior officer's ship on the South American station from 1882–85. She was sold for scrap two years later.

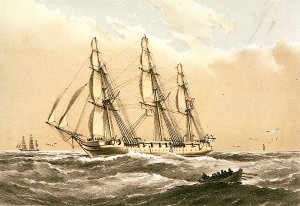

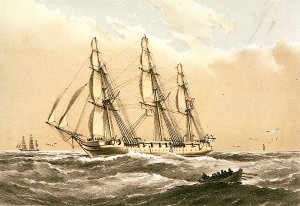

Amethyst at anchor

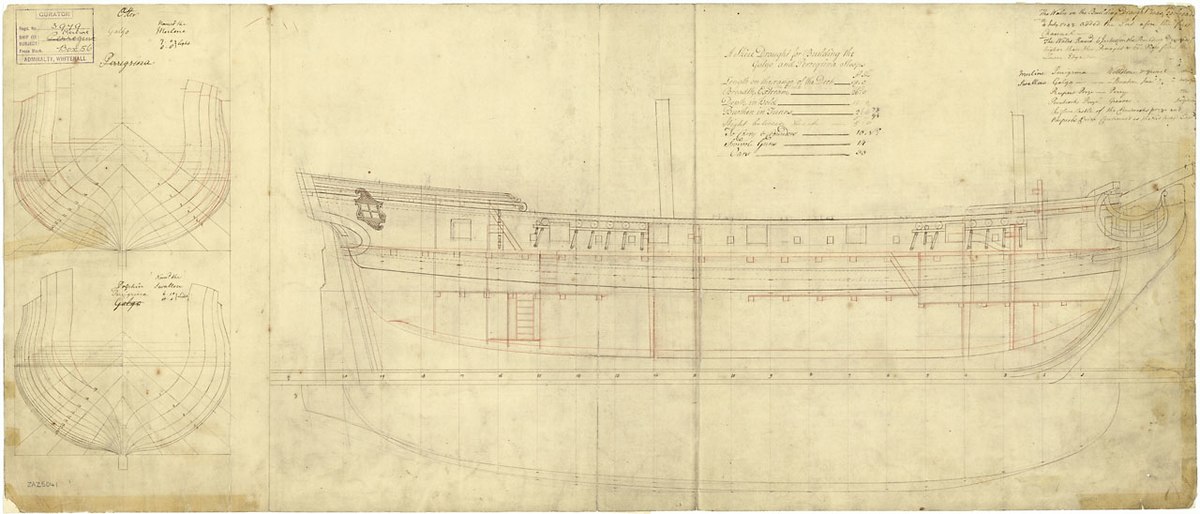

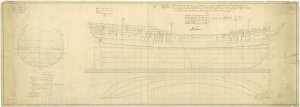

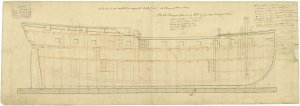

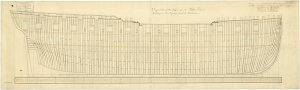

Design and description

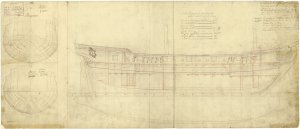

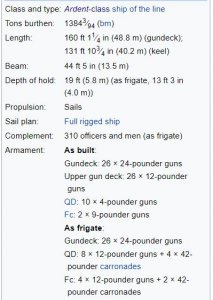

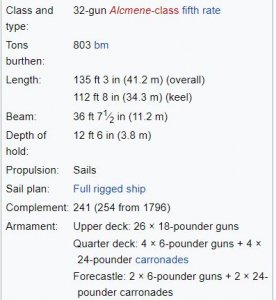

Amethyst was 220 feet (67.1 m) long between perpendiculars, had a beam of 37 feet (11.3 m) and had a draught of 18 feet (5.5 m). The ship displaced 1,934 long tons (1,965 t) and had a burthen of 1,405 tons. Her crew consisted of 225 officers and enlisted men. Unlike her iron-hulled contemporaries, the ship's wooden hull prevented any use of watertight transverse bulkheads.

The ship had one two-cylinder horizontal compound expansion steam engine made by J. & G. Rennie, driving a single 15-foot (4.6 m) propeller. Six cylindrical boilers provided steam to the engine at a working pressure of 60 psi (414 kPa; 4 kgf/cm2). The engine produced a total of 2,144 indicated horsepower (1,599 kW) which gave Amethyst a maximum speed of 13.244 knots (24.528 km/h; 15.241 mph) during her sea trials. The ship carried 270 long tons (270 t) of coal, enough to steam between 2,060–2,500 nautical miles (3,820–4,630 km; 2,370–2,880 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). Amethyst was ship rigged and had a sail area of 18,000 square feet (1,672 m2). The lower masts were made of iron, but the other masts were wood. The ship, and her sisters, were excellent sailors and their best speed under sail alone was approximately that while under steam. Ballard says that all the ships of this class demonstrated "excellent qualities of handiness, steadiness and seaworthiness". Her propeller could be hoisted up into the stern of the ship to reduce drag while under sail. During her refit in 1878, Amethyst was re-rigged as a barque.

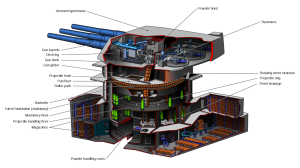

The ship was initially armed with a mix of 64-pounder 71-cwt[Note 1] and 64-cwt rifled muzzle-loading guns. The twelve 71-cwt guns were mounted on the broadside while the two lighter 64-cwt guns were mounted underneath the forecastle and poop deck as chase guns. In 1878, the ship's 71-cwt guns were replaced by 64-cwt guns.

Service

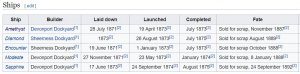

Amethyst was laid down at Devonport Dockyard on 28 July 1871. She was launched on 19 April 1873 and completed in July 1873. Her sisters cost approximately £77,000 each. The ship was first assigned as the senior officer's ship for the South American side of the South Atlantic, but she was diverted en route to Ghana to support British forces during the Third Anglo-Ashanti War.

Amethyst remained on the South American station until she was transferred to the Pacific Station in 1875 after she was relieved by Volage. In May 1877, the crew of the Peruvian ironclad Huáscar rebelled against the government and began harassing British shipping. Amethyst and the unarmored frigate Shah were ordered to capture the rebel ship and finally found her in the late afternoon of 29 May off the port of Ilo. After Huáscar refused an offer to surrender, the British ships fired upon her in what came to be known as the Battle of Pacocha. Shah's deep draught forced her to keep to seaward, therefore Amethyst was ordered into shallower inshore waters south of the Peruvian ironclad to deter her from escaping into neutral Chilean waters. The corvette's 64-pounder guns were unable to significantly damage the ironclad in any way, but her opponent's gunnery was atrocious and neither British ship suffered more than some damage to their rigging. Huáscar escaped with little damage after nightfall and surrendered to the Peruvian government the following day.

Amethyst returned home in July 1878 for a lengthy refit and was recommissioned in 1882 to return as the senior officer's ship for southeastern South America until she returned in late 1885 and was paid off. The ship was sold for scrap in November 1887.

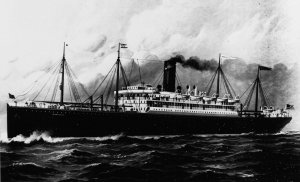

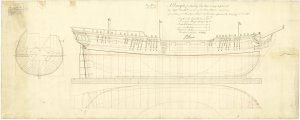

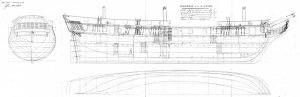

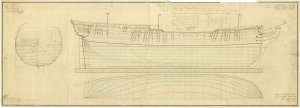

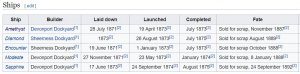

H.M.S. Diamond Print

The Amethyst-class corvettes were the last wooden warships built at a royal dockyard. Built in the early 1870s, they mostly served overseas and were retired early as they were regarded as hopelessly obsolete by the late 1880s.

HMS Diamond in Farm Cove, Sydney c. 1887

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Amethyst_(1873)

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

19 April 1873 – Launch of HMS Amethyst, the lead ship of the Amethyst-class corvettes built for the Royal Navy in the early 1870s.

HMS Amethyst was the lead ship of the Amethyst-class corvettes built for the Royal Navy in the early 1870s. She participated in the Third Anglo-Ashanti War in 1873 before serving as the senior officer's ship for the South American side of the South Atlantic. The ship was transferred to the Pacific Station in 1875 and fought in the Battle of Pacocha against the rebellious Peruvian ironclad warship Huáscar two years later. This made her the only British wooden sailing ship ever to fight an armoured opponent. After a lengthy refit, Amethystagain served as the senior officer's ship on the South American station from 1882–85. She was sold for scrap two years later.

Amethyst at anchor

Design and description

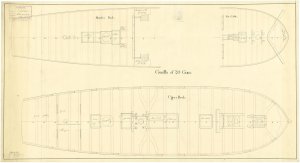

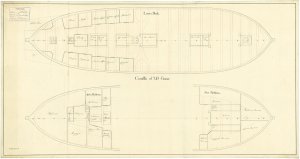

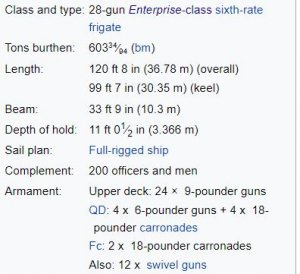

Amethyst was 220 feet (67.1 m) long between perpendiculars, had a beam of 37 feet (11.3 m) and had a draught of 18 feet (5.5 m). The ship displaced 1,934 long tons (1,965 t) and had a burthen of 1,405 tons. Her crew consisted of 225 officers and enlisted men. Unlike her iron-hulled contemporaries, the ship's wooden hull prevented any use of watertight transverse bulkheads.

The ship had one two-cylinder horizontal compound expansion steam engine made by J. & G. Rennie, driving a single 15-foot (4.6 m) propeller. Six cylindrical boilers provided steam to the engine at a working pressure of 60 psi (414 kPa; 4 kgf/cm2). The engine produced a total of 2,144 indicated horsepower (1,599 kW) which gave Amethyst a maximum speed of 13.244 knots (24.528 km/h; 15.241 mph) during her sea trials. The ship carried 270 long tons (270 t) of coal, enough to steam between 2,060–2,500 nautical miles (3,820–4,630 km; 2,370–2,880 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). Amethyst was ship rigged and had a sail area of 18,000 square feet (1,672 m2). The lower masts were made of iron, but the other masts were wood. The ship, and her sisters, were excellent sailors and their best speed under sail alone was approximately that while under steam. Ballard says that all the ships of this class demonstrated "excellent qualities of handiness, steadiness and seaworthiness". Her propeller could be hoisted up into the stern of the ship to reduce drag while under sail. During her refit in 1878, Amethyst was re-rigged as a barque.

The ship was initially armed with a mix of 64-pounder 71-cwt[Note 1] and 64-cwt rifled muzzle-loading guns. The twelve 71-cwt guns were mounted on the broadside while the two lighter 64-cwt guns were mounted underneath the forecastle and poop deck as chase guns. In 1878, the ship's 71-cwt guns were replaced by 64-cwt guns.

Service

Amethyst was laid down at Devonport Dockyard on 28 July 1871. She was launched on 19 April 1873 and completed in July 1873. Her sisters cost approximately £77,000 each. The ship was first assigned as the senior officer's ship for the South American side of the South Atlantic, but she was diverted en route to Ghana to support British forces during the Third Anglo-Ashanti War.

Amethyst remained on the South American station until she was transferred to the Pacific Station in 1875 after she was relieved by Volage. In May 1877, the crew of the Peruvian ironclad Huáscar rebelled against the government and began harassing British shipping. Amethyst and the unarmored frigate Shah were ordered to capture the rebel ship and finally found her in the late afternoon of 29 May off the port of Ilo. After Huáscar refused an offer to surrender, the British ships fired upon her in what came to be known as the Battle of Pacocha. Shah's deep draught forced her to keep to seaward, therefore Amethyst was ordered into shallower inshore waters south of the Peruvian ironclad to deter her from escaping into neutral Chilean waters. The corvette's 64-pounder guns were unable to significantly damage the ironclad in any way, but her opponent's gunnery was atrocious and neither British ship suffered more than some damage to their rigging. Huáscar escaped with little damage after nightfall and surrendered to the Peruvian government the following day.

Amethyst returned home in July 1878 for a lengthy refit and was recommissioned in 1882 to return as the senior officer's ship for southeastern South America until she returned in late 1885 and was paid off. The ship was sold for scrap in November 1887.

H.M.S. Diamond Print

The Amethyst-class corvettes were the last wooden warships built at a royal dockyard. Built in the early 1870s, they mostly served overseas and were retired early as they were regarded as hopelessly obsolete by the late 1880s.

HMS Diamond in Farm Cove, Sydney c. 1887

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Amethyst_(1873)

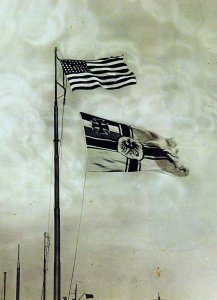

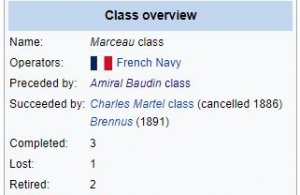

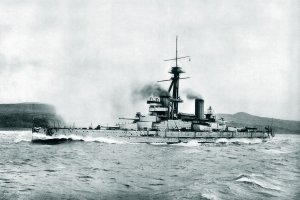

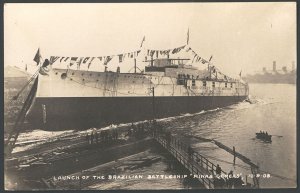

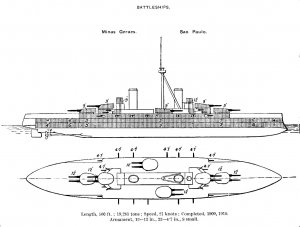

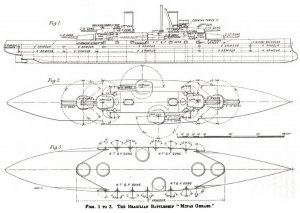

papers and journals around the world, particularly in Britain and Germany, speculated that Brazil was acting as a proxy for a naval power which would take possession of the two dreadnoughts soon after completion, as they did not believe that a previously insignificant geopolitical power would contract for such powerful warships. Despite this, the United States actively attempted to court Brazil as an ally; caught up in the spirit, U.S. naval journals began using terms like "Pan Americanism" and "Hemispheric Cooperation".

papers and journals around the world, particularly in Britain and Germany, speculated that Brazil was acting as a proxy for a naval power which would take possession of the two dreadnoughts soon after completion, as they did not believe that a previously insignificant geopolitical power would contract for such powerful warships. Despite this, the United States actively attempted to court Brazil as an ally; caught up in the spirit, U.S. naval journals began using terms like "Pan Americanism" and "Hemispheric Cooperation".