Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

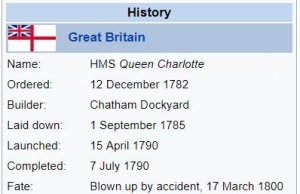

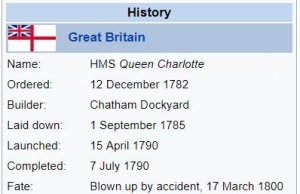

15 April 1790 – Launch of HMS Queen Charlotte, a 100-gun first-rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, at Chatham.

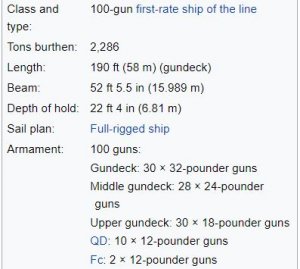

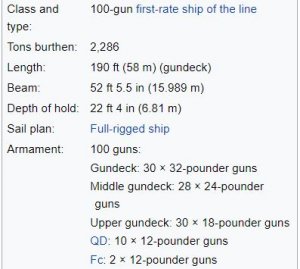

HMS Queen Charlotte was a 100-gun first-rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, launched on 15 April 1790 at Chatham. She was built to the draught of Royal George designed by Sir Edward Hunt, though with a modified armament.

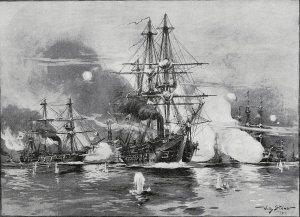

In 1794 Queen Charlotte was the flagship of Admiral Lord Howe at the Battle of the Glorious First of June, and in 1795 she took part in the Battle of Groix.

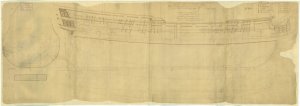

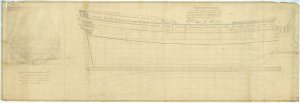

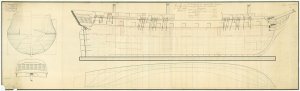

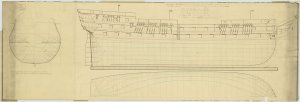

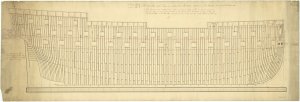

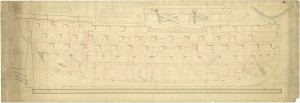

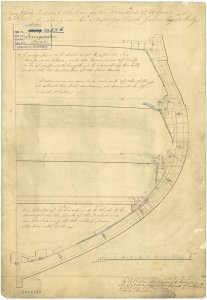

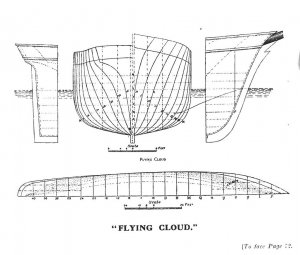

Scale: 1:48. Plan showing the body plan, sheer lines, and longitudinal half-breadth for 'Royal George' (1788), and a year later for 'Queen Charlotte' (1790), both 100-gun First Rate, three-deckers, after the design had been lengthened by three feet.

Fate

At about 6am on 17 March 1800, whilst operating as the flagship of Vice-Admiral Lord Keith, Queen Charlotte was reconnoitering the island of Capraia, in the Tuscan Archipelago, when she caught fire. Keith was not aboard at the time and observed the disaster from the shore.

The fire was believed to have resulted from someone having accidentally thrown loose hay on a match tub. Two or three American vessels lying at anchor off Leghorn were able to render assistance, losing several men in the effort as the vessel's guns exploded in the heat. Captain A. Todd wrote several accounts of the disaster that he gave to sailors to give to the Admiralty should they survive. He himself perished with his ship. The crew was unable to extinguish the flames and at about 11am the ship blew up with the loss of 673 officers and men.

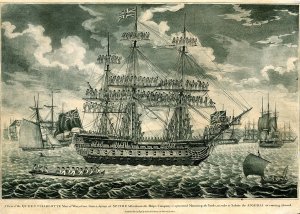

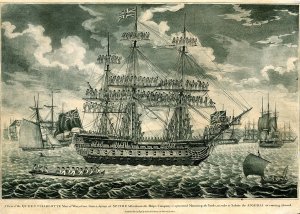

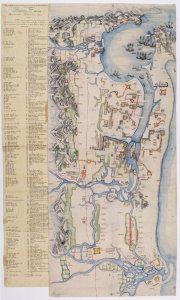

This review at Spithead, which the artist may have witnessed, demonstrated England's sea power just before the French Revolutionary Wars. In this interpretation, ships ride at anchor in Spithead, opposite Portsmouth, the most important naval base in the country. To the left of centre, the dominant ship is Admiral Lord Howe's flagship, 'Queen Charlotte', a new 104-gun first-rate. Her figurehead is clearly shown, and she fires a salute in honour of the Admiral who is being rowed over in his barge in the foreground. 'Queen Charlotte' flies a Union flag at the main, since Lord Howe, as senior Admiral of the Red was Admiral of the Fleet. To the left, other ships are portrayed anchored in lines both to the right of the 'Queen Charlotte', and on the horizon, indicating the strength and power of the Navy. It is not clear what occasion was being recorded by the artist, but it may have been connected with Russian armament. 'Queen Charlotte' was also Howe's flagship at the Battle of the Glorious First of June in 1794. Howe was nicknamed 'Black Dick' by his officers and men due to his dark complexion and taciturnity. The Scottish born artist was heavily influenced by 17th century Dutch marine artists. He is best known for his works in this style, although he also produced larger history paintings.

Scale: 1:60. A contemporary full hull model of the three-decker 100-gun first-rate ‘Queen Charlotte’ built plank on frame in the ‘Georgian’ style. The quality and finish of the model is exceptional both in the construction and the lavish carved and painted decoration. The ‘Queen Charlotte’ was launched at Chatham Royal Dockyard in 1789 and measured 190 feet along the gun deck by 52 feet in the beam and had tonnage of 2278. She was Lord Howe’s flagship at the Battle of the First of June in 1794 and also took part in Lord Bridport’s action off Croix in 1795. She was accidentally set alight off Leghorn in 1800 with the loss of nearly 700 lives.

Umpire class (Hunt)

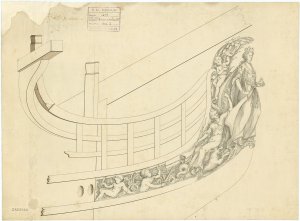

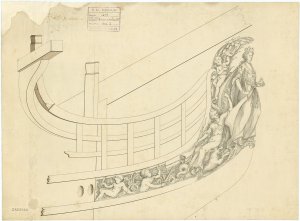

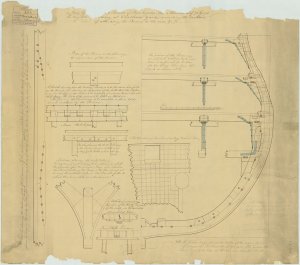

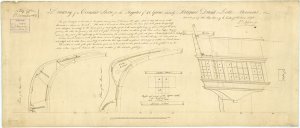

Scale: 1:24. Plan showing the starboard profile of the figurehead for 'Queen Charlotte' (1790), a 100-gun First Rate, three-decker.

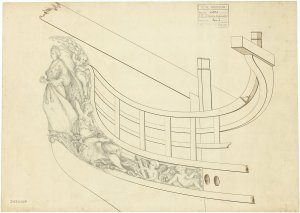

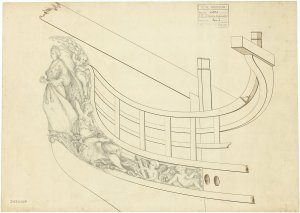

Scale: 1:24. Plan showing the port profile of the figurehead for 'Queen Charlotte' (1790), a 100-gun First Rate, three-decker.

A view of the Queen Charlotte Man of War, of 100 guns, laying at Spithead, where in the ships Company is represented Manning the Yards, in order to salute the Admiral on coming aboard (PAF7981)

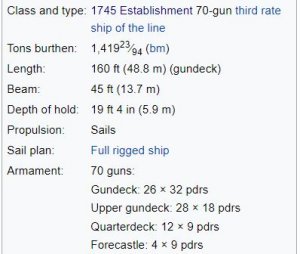

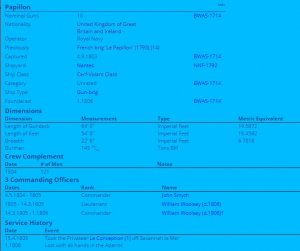

en.wikipedia.org

https://collections.rmg.co.uk/colle...el-341405;browseBy=vessel;vesselFacetLetter=Q

en.wikipedia.org

https://collections.rmg.co.uk/colle...el-341405;browseBy=vessel;vesselFacetLetter=Q

15 April 1790 – Launch of HMS Queen Charlotte, a 100-gun first-rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, at Chatham.

HMS Queen Charlotte was a 100-gun first-rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, launched on 15 April 1790 at Chatham. She was built to the draught of Royal George designed by Sir Edward Hunt, though with a modified armament.

In 1794 Queen Charlotte was the flagship of Admiral Lord Howe at the Battle of the Glorious First of June, and in 1795 she took part in the Battle of Groix.

Scale: 1:48. Plan showing the body plan, sheer lines, and longitudinal half-breadth for 'Royal George' (1788), and a year later for 'Queen Charlotte' (1790), both 100-gun First Rate, three-deckers, after the design had been lengthened by three feet.

Fate

At about 6am on 17 March 1800, whilst operating as the flagship of Vice-Admiral Lord Keith, Queen Charlotte was reconnoitering the island of Capraia, in the Tuscan Archipelago, when she caught fire. Keith was not aboard at the time and observed the disaster from the shore.

The fire was believed to have resulted from someone having accidentally thrown loose hay on a match tub. Two or three American vessels lying at anchor off Leghorn were able to render assistance, losing several men in the effort as the vessel's guns exploded in the heat. Captain A. Todd wrote several accounts of the disaster that he gave to sailors to give to the Admiralty should they survive. He himself perished with his ship. The crew was unable to extinguish the flames and at about 11am the ship blew up with the loss of 673 officers and men.

This review at Spithead, which the artist may have witnessed, demonstrated England's sea power just before the French Revolutionary Wars. In this interpretation, ships ride at anchor in Spithead, opposite Portsmouth, the most important naval base in the country. To the left of centre, the dominant ship is Admiral Lord Howe's flagship, 'Queen Charlotte', a new 104-gun first-rate. Her figurehead is clearly shown, and she fires a salute in honour of the Admiral who is being rowed over in his barge in the foreground. 'Queen Charlotte' flies a Union flag at the main, since Lord Howe, as senior Admiral of the Red was Admiral of the Fleet. To the left, other ships are portrayed anchored in lines both to the right of the 'Queen Charlotte', and on the horizon, indicating the strength and power of the Navy. It is not clear what occasion was being recorded by the artist, but it may have been connected with Russian armament. 'Queen Charlotte' was also Howe's flagship at the Battle of the Glorious First of June in 1794. Howe was nicknamed 'Black Dick' by his officers and men due to his dark complexion and taciturnity. The Scottish born artist was heavily influenced by 17th century Dutch marine artists. He is best known for his works in this style, although he also produced larger history paintings.

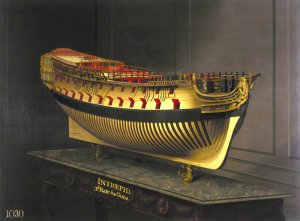

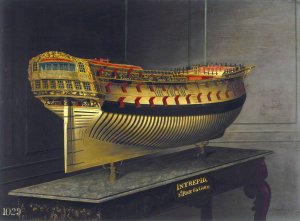

Scale: 1:60. A contemporary full hull model of the three-decker 100-gun first-rate ‘Queen Charlotte’ built plank on frame in the ‘Georgian’ style. The quality and finish of the model is exceptional both in the construction and the lavish carved and painted decoration. The ‘Queen Charlotte’ was launched at Chatham Royal Dockyard in 1789 and measured 190 feet along the gun deck by 52 feet in the beam and had tonnage of 2278. She was Lord Howe’s flagship at the Battle of the First of June in 1794 and also took part in Lord Bridport’s action off Croix in 1795. She was accidentally set alight off Leghorn in 1800 with the loss of nearly 700 lives.

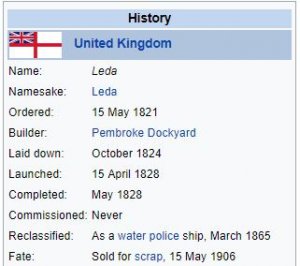

Umpire class (Hunt)

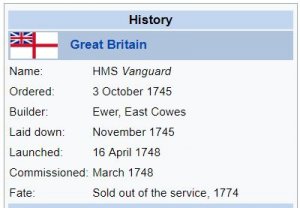

- Royal George 100 (1788) – broken up 1822

- Queen Charlotte 100 (1790) – an accidental fire in 1800 destroyed her and killed 673 of her crew of 859

- Queen Charlotte 104 (1810) – renamed Excellent 1860, broken up 1892

Scale: 1:24. Plan showing the starboard profile of the figurehead for 'Queen Charlotte' (1790), a 100-gun First Rate, three-decker.

Scale: 1:24. Plan showing the port profile of the figurehead for 'Queen Charlotte' (1790), a 100-gun First Rate, three-decker.

A view of the Queen Charlotte Man of War, of 100 guns, laying at Spithead, where in the ships Company is represented Manning the Yards, in order to salute the Admiral on coming aboard (PAF7981)

Line

Line