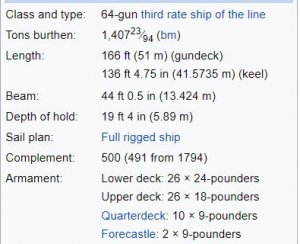

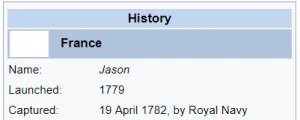

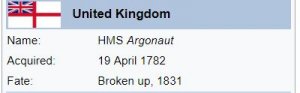

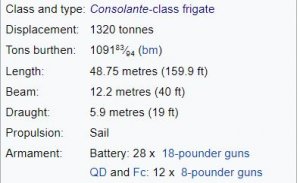

Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

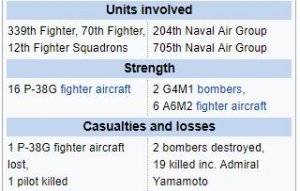

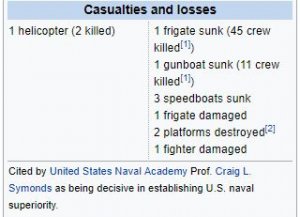

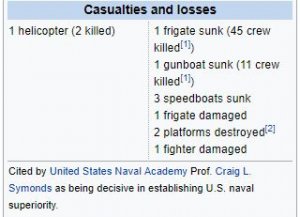

18 April 1988 - April 18 Operation Praying Mantis - In the largest US naval engagement since World War II, the U.S. Navy defeats Iranian naval forces in retaliation for the mining of the USS Samuel B. Roberts during a patrol mission.

Operation Praying Mantis was an attack on 18 April 1988, by U.S. forces within Iranian territorial waters in retaliation for the Iranian mining of the Persian Gulf during the Iran–Iraq War and the subsequent damage to an American warship.

On 14 April, the guided missile frigate USS

Samuel B. Roberts struck a mine while deployed in the Persian Gulf as part of

Operation Earnest Will, the 1987–88 convoy missions in which U.S. warships escorted reflagged Kuwaiti oil tankers to protect them from Iranian attacks. The explosion blew a 4.5 m (15-foot) hole in the

Samuel B. Roberts's hull and nearly sank it. The crew saved their ship with no loss of life, and the

Samuel B. Roberts was towed to

Dubai,

United Arab Emirates on 16 April. After the mining, U.S. Navy divers recovered other mines in the area. When the serial numbers were found to match those of mines seized along with the

Iran Ajr the previous September, U.S. military officials planned a retaliatory operation against Iranian targets in the Persian Gulf.

According to Bradley Peniston, the attack by the U.S. helped pressure Iran to agree to a ceasefire with Iraq later that summer, ending the eight-year conflict between the Persian Gulf neighbors.

On 6 November 2003, the International Court of Justice ruled that "the actions of the United States of America against Iranian oil platforms on 19 October 1987 (Operation Nimble Archer) and 18 April 1988 (Operation Praying Mantis) cannot be justified as measures necessary to protect the essential security interests of the United States of America." However, the International Court of Justice dismissed Iran's claim that the attack by United States Navy was a breach of the 1955 Treaty of Amity between the two countries as it only pertained to vessels, not platforms.

This battle was the largest of the five major U.S. surface engagements since the Second World War, which also include the Battle of Chumonchin Chan during the

Korean War, the Gulf of Tonkin incident and the Battle of Dong Hoi during the Vietnam War, and the Action in the Gulf of Sidra in 1986. It also marked the U.S. Navy's first exchange of anti-ship missiles with opposing ships and the only occasion since World War II on which the US Navy sank a major surface combatant.

By the end of the operation, U.S. air and surface units had sunk, or severely damaged, half of Iran's operational fleet.

The Iranian frigate

Sahand attacked by aircraft of U.S. Navy Carrier Air Wing 11 after the guided missile frigate USS

Samuel B. Roberts struck an Iranian mine

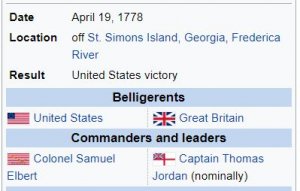

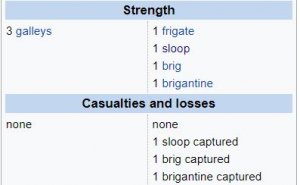

Battle

On 18 April, the U.S. Navy attacked with several groups of surface warships, plus aircraft from the aircraft carrier USS

Enterprise, and her cruiser escort, USS

Truxtun. The action began with coordinated strikes by two surface groups.

One Surface Action Group, or SAG, consisting of the destroyers USS

Merrill (including embarked LAMPS

MK I Helicopter Detachment HSL-35 Det 1) and USS

Lynde McCormick, plus the amphibious transport dock USS

Trenton and its embarked Marine Air-Ground Task Force (Contingency MAGTF 2-88 from Camp LeJeune, NC) and the LAMPS (Light Airborne MultiPurpose System) Helicopter Detachment (HSL-44 Det 5) from USS

Samuel B. Roberts, was ordered to destroy the guns and other military facilities on the Sassan oil platform. At 8am, the SAG commander, who was also the commander of Destroyer Squadron 9, ordered the

Merrill to radio a warning to the occupants of the platform, telling them to abandon it. The SAG waited 20 minutes, then opened fire. The oil platform fired back with twin-barrelled 23 mm

ZU-23 guns. The SAG's guns eventually disabled some of the ZU-23s, and platform occupants radioed a request for a cease-fire. The SAG complied. After a tug carrying more personnel had cleared the area, the ships resumed exchanging fire with the remaining ZU-23s, and ultimately disabled them. Cobra helicopters completed the destruction of enemy resistance. The Marines boarded the platform, and recovered a single wounded survivor (who was transported to Bahrain), some small arms, and intelligence. The Marines planted explosives, left the platform, and detonated them. The SAG was then ordered to proceed north to the Rakhsh oil platform to destroy it.

A starboard bow view of the Iranian destroyer escort ITS

Faramarz (DE 74), redesignated as IRS

Sahand (F 74)

As the SAG departed the Sassan oil field, two Iranian F-4s made an attack run, but broke off when

Lynde McCormick locked its fire control radar on the aircraft. Halfway to the Rahksh oil platform, the attack was called off in an attempt to ease pressure on the Iranians and signal a desire for de-escalation.

The other group, which included guided missile cruiser USS

Wainwright and frigates USS

Simpson and USS

Bagley , attacked the Sirri oil platform. Navy

SEALs were assigned to capture, occupy and destroy the Sirri platform but due to heavy pre-assault damage from naval gunfire, it was determined that an assault was not required.

Iran responded by dispatching Boghammar speedboats to attack various targets in the Persian Gulf, including the American-flagged supply ship

Willie Tide, the Panamanian-flagged

oil rig Scan Bay and the British tanker

York Marine. All of these vessels were damaged in different degrees. After the attacks, A-6E Intruder aircraft launched from USS

Enterprise, were directed to the speedboats by an American frigate. The two VA-95, aircraft, piloted by "Lizards" Lieutenant Commander James Engler and Lieutenant Paul Webb, dropped Rockeye cluster bombs on the speedboats, sinking one and damaging several others, which then fled to the Iranian-controlled island of

Abu Musa.

Combat Patch of Operation Praying Mantis

Action continued to escalate.

Joshan, an Iranian

Combattante II Kaman-class fast attack craft, challenged USS

Wainwright and Surface Action Group Charlie. The commanding officer of

Wainwright directed a final warning (of a series of warnings) stating that

Joshan was to "stop your engines, abandon ship, I intend to sink you".

Joshan responded by firing a Harpoon missile at them. The missile was successfully lured away by chaff.

Simpson responded to the challenge by firing four Standard missiles, while

Wainwright followed with one Standard missile.

[8] All missiles hit and destroyed the Iranian ship's superstructure but did not immediately sink it, so

Bagley fired a Harpoon of its own. The missile did not find the target. SAG Charlie closed on

Joshan, with

Simpson, then

Bagley and

Wainwright firing guns to sink the crippled Iranian ship.

Two Iranian

F-4 Phantom fighters were orbiting about 48 km (26 nmi) away when

Wainwright decided to drive them away.

Wainwright fired two

Extended Range Standard missiles, one of which detonated near an F-4, blowing off part of its wing and peppering the fuselage with shrapnel. The F-4s withdrew, and the Iranian pilot landed his damaged airplane at Bandar Abbas.

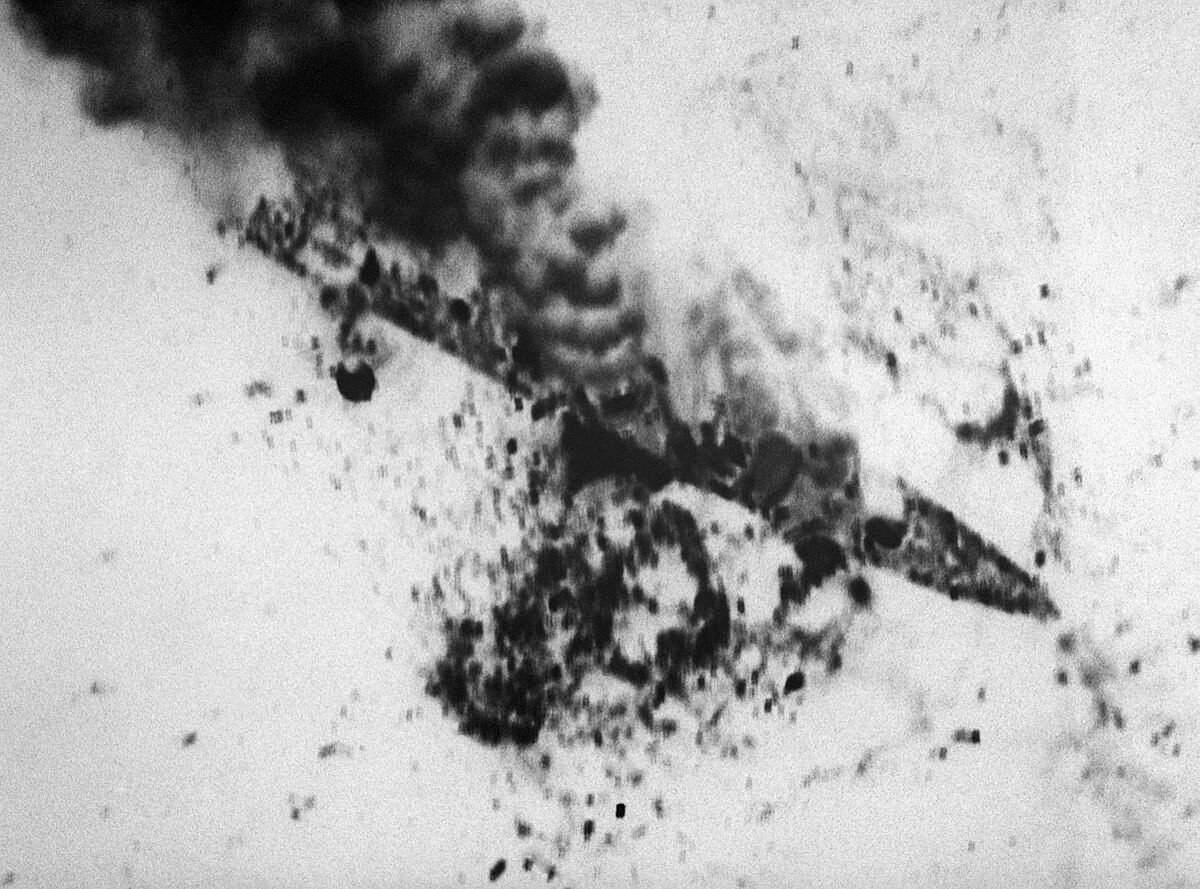

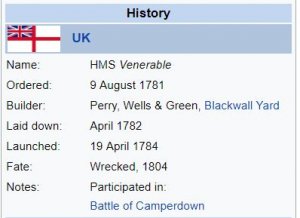

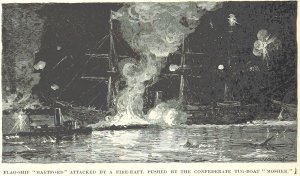

Fighting continued when the Iranian frigate

Sahand departed Bandar Abbas and challenged elements of an American surface group. The frigate was spotted by two A-6Es from VA-95 while they were flying surface combat air patrol for USS

Joseph Strauss.

The Iranian frigate

Sahand burning from bow to stern on 18 April 1988 after being attacked.

Sahand fired missiles at the A-6Es, which replied with two Harpoon missiles and four laser-guided

Skipper missiles.

Joseph Strauss fired a Harpoon. Most, if not all of the shots scored hits, causing heavy damage and fires. Fires blazing on

Sahand's decks eventually reached her munitions magazines, causing an explosion that sank her.

Late in the day, the Iranian frigate

Sabalan departed from its berth and fired a surface-to-air missile at several A-6Es from VA-95. The A-6Es then dropped a

Mark 82 laser-guided bomb into

Sabalan's stack, crippling the ship and leaving it burning. The Iranian frigate, stern partially submerged, was taken in tow by an Iranian tug, and was repaired and eventually returned to service. VA-95's aircraft, as ordered, did not continue the attack. The A-6 pilot who crippled

Sabalan, LCDR James Engler, was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross by Admiral William J. Crowe, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, for the actions against the

Sabalan and the Iranian gunboats.

In retaliation for the attacks, Iran fired Silkworm missiles (suspected to be the HY-4 version) from land bases against SAG Delta in the Strait of Hormuz and against USS

Gary in the northern central

Persian Gulf, but all missed due to the evasive maneuvers and use of decoys by the ships. A missile was probably shot down by

Gary's 76 mm (3.0 in) gun. The Pentagon and the Reagan Administration later denied that any Silkworm missile attacks took place probably since it was the only way to keep the situation from escalating further as they had promised before publicly that any such attacks would merit retaliation against targets on Iranian soil.

Disengagement

Following the attack on

Sabalan, U.S. naval forces were ordered to assume a de-escalatory posture, giving Iran a way out and avoiding further combat. Iran took the offer and combat ceased, though both sides remained on alert, and near-clashes occurred throughout the night and into the next day as the forces steamed within the Gulf. Two days after the battle,

Lynde McCormick was directed to escort a U.S. oiler out through the Strait of Hormuz, while a Scandinavian-flagged merchant remained near, probably for protection. While the ships remained alert, no hostile indications were received, and the clash was over.

Aftermath

By the end of the operation, American Marines, ships and aircraft had destroyed Iranian naval and intelligence facilities on two inoperable oil platforms in the

Persian Gulf, and sank at least three armed Iranian

speedboats, one Iranian frigate and one fast attack gunboat. One other Iranian frigate was damaged in the battle.

Sabalan was repaired in 1989 and has since been upgraded, and is still in service with the Iranian navy. The fires eventually burned themselves out but the damage to the infrastructure forced the demolition of the Sirri platforms after the war. The site was built up again for oil production by French and Russian oil companies, after buying the drilling rights from the Iranian government.

The U.S. side suffered two casualties, the crew of a Marine Corps

AH-1T Sea Cobra helicopter gunship. The Cobra, attached to USS

Trenton, was flying reconnaissance from

Wainwright and crashed sometime after dark about 15 miles southwest of

Abu Musa island. The bodies of the lost personnel were recovered by Navy divers in May, and the wreckage of the helicopter was raised later that month. Navy officials said it showed no sign of battle damage. In his recent book "Tanker War", author

Lee Allen Zatarain indicates there was some indication they may have crashed while evading hostile fire from the island.

A month later, the guided missile cruiser

USS Vincennes arrived, summoned in haste to protect the frigate

Samuel B. Roberts as it was hauled back to the United States. On 3 July,

Vincennes shot down

Iran Air Flight 655, killing all 290 crew and passengers. The U.S. government said the crew of

Vincennes mistook the Iranian Airbus for an attacking

F-14 fighter, despite it being a commercial airliner flying a scheduled route. The Iranian government alleged that

Vincennes knowingly shot down a civilian aircraft.

International Court of Justice

On 6 November 2003 the International Court of Justice dismissed a claim by Iran and a counter claim by the United States' for reparations for breach of a 1955 'Treaty of Amity' between the two countries. In short the court rejected both claim and counter claim because the 1955 treaty protected only "freedom of trade and navigation between the territories of the parties" and because of the US trade embargo on Iran at the time, no direct trade or navigation between the two was affected by the conflict.

The court did state that "the actions of the United States of America against Iranian oil platforms on 19 October 1987 (Operation Nimble Archer) and 18 April 1988 (Operation Praying Mantis) cannot be justified as measures necessary to protect the essential security interests of the United States of America." The Court ruled that it "...cannot however uphold the submission of the Islamic Republic of Iran that those actions constitute a breach of the obligations of the United States of America under Article X, paragraph 1, of that Treaty, regarding freedom of commerce between the territories of the parties, and that, accordingly, the claim of the Islamic Republic of Iran for reparation also cannot be upheld;".

U.S. naval order of battle

Samuel B. Roberts

Samuel B. Roberts is carried away aboard

Mighty Servant 2 after hitting a

mine in the Persian Gulf.

- Officer in Tactical Command: Commander Joint Task Force Middle East (aboard USS Coronado)

- Battle Group Commander: Commander, Cruiser/Destroyer Group Three (aboard USS Enterprise)

Surface Action Group Bravo

- On Scene Commander: Commander, Destroyer Squadron Nine (Embarked on Merrill)

- USS Merrill – destroyer

- USS Lynde McCormick – guided missile destroyer

- USS Trenton – amphibious transport dock

- Marine Air-Ground Task Force (MAGTF) 2–88 (4 AH-1T, 2 UH-1, 2 CH-46)

- Helicopter AntiSubmarine Squadron 44 Detachment 5 – LAMPS Helicopter (SH-60B)

Surface Action Group Charlie

- OSC: CO, USS Wainwright

- USS Wainwright – guided missile cruiser

- USS Bagley – frigate

- USS Simpson – guided missile frigate

- SEAL platoon

Surface Action Group Delta

- OSC: Commander Destroyer Squadron Twenty Two (Embarked on Jack Williams)

- USS Jack Williams – guided missile frigate

- USS O'Brien – destroyer

- USS Joseph Strauss – guided missile destroyer

Air support

- Elements of Carrier Air Wing Eleven operating from aircraft carrier USS Enterprise

- A-6E & KA-6D Intruders of VA-95 operating from aircraft carrier USS Enterprise

Ship maintenance and support

- USS Samuel Gompers – destroyer tender – performed ship maintenance and repairs operating off the coast of Oman

- USS Wabash – fast attack oiler – provided underway replenishment of fuel, ammunition, and supplies to the USS Enterprise Battle Group

en.wikipedia.org

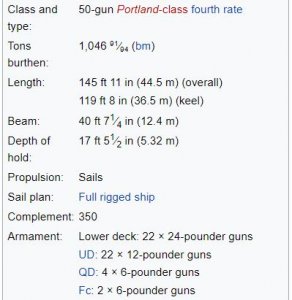

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iranian_frigate_Sahand

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

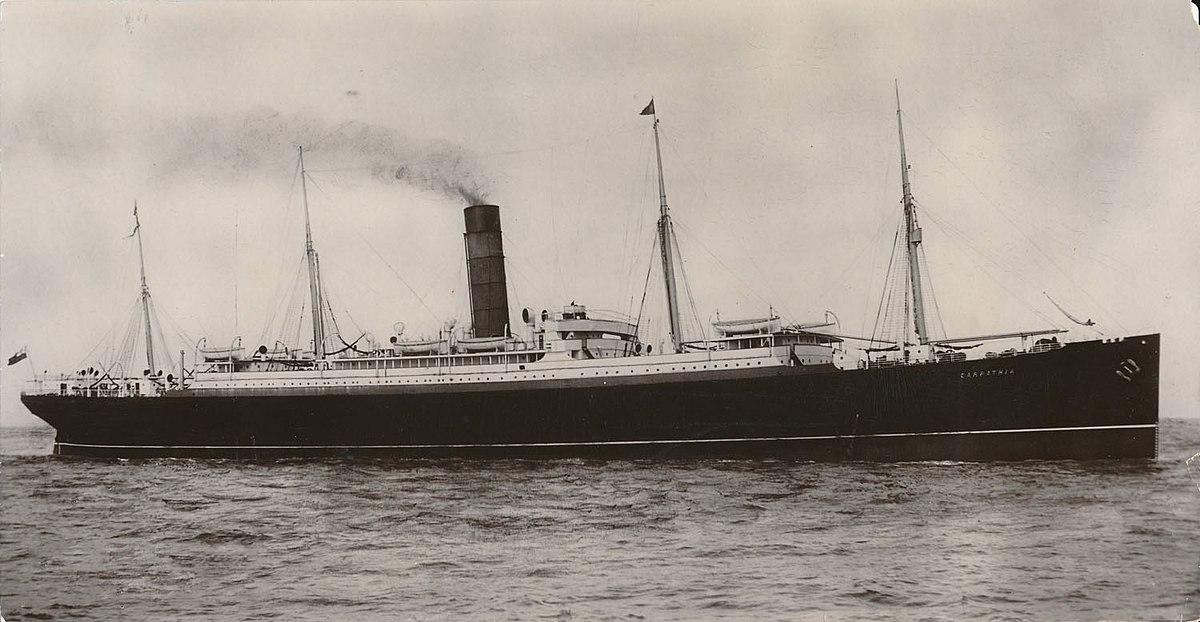

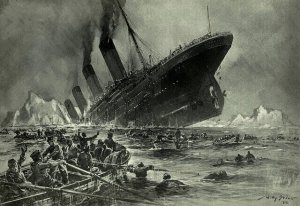

of the Titanic disaster spread on shore, and the humble Carpathia became the center of intense media attention as she steamed westward towards New York at 14 knots. Hundreds of wireless messages were being sent from Cape Race and other shore stations addressed to Captain Rostron from relatives of Titanic passengers and journalists demanding details in exchange for money. Rostron ordered that no news stories would be transmitted directly to the press, deferring such responsibilities to the White Star offices as Cottam provided details to Titanic's sister ship,

of the Titanic disaster spread on shore, and the humble Carpathia became the center of intense media attention as she steamed westward towards New York at 14 knots. Hundreds of wireless messages were being sent from Cape Race and other shore stations addressed to Captain Rostron from relatives of Titanic passengers and journalists demanding details in exchange for money. Rostron ordered that no news stories would be transmitted directly to the press, deferring such responsibilities to the White Star offices as Cottam provided details to Titanic's sister ship,