Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

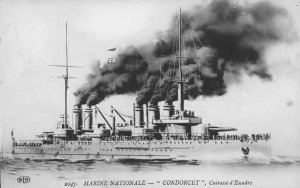

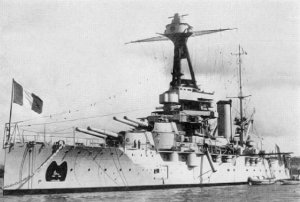

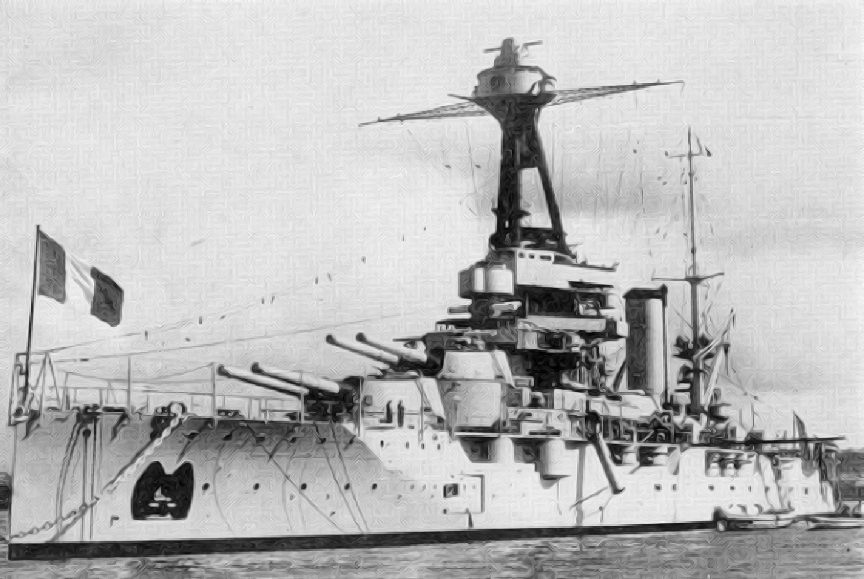

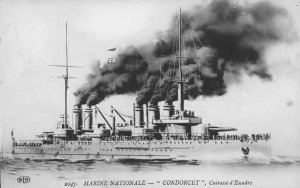

20 April 1909 – Launch of French Condorcet, one of the six Danton-class semi-dreadnought battleships built for the French Navy in the early 1900s

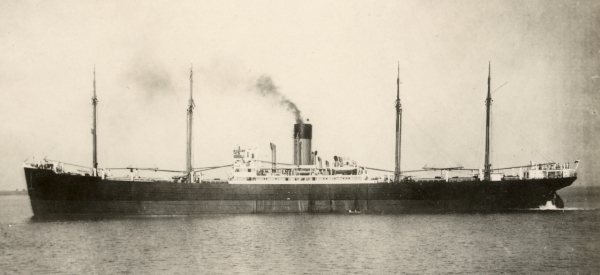

Condorcet was one of the six

Danton-class semi-dreadnought battleships built for the

French Navy in the early 1900s. When

World War I began in August 1914, she unsuccessfully searched for the German

battlecruiser SMS Goeben and the

light cruiser SMS Breslau in the Western and Central Mediterranean. Later that month, the ship participated in the

Battle of Antivari in the

Adriatic Sea and helped to sink an

Austro-Hungarian protected cruiser.

Condorcet spent most of the rest of the war blockading the

Straits of Otranto and the

Dardanelles to keep German, Austro-Hungarian and Turkish warships bottled up.

After the war, she was modernized in 1923–25 and subsequently became a

training ship. In 1931, the ship was converted into an

accommodation hulk.

Condorcet was captured intact when the Germans occupied

Vichy France in November 1942 and was used by them to house sailors of their navy (

Kriegsmarine). She was badly damaged by Allied bombing in 1944, but was later

raised and

scrapped by 1949.

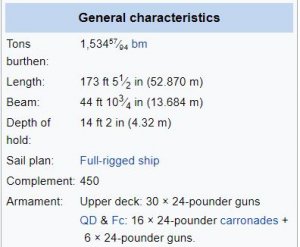

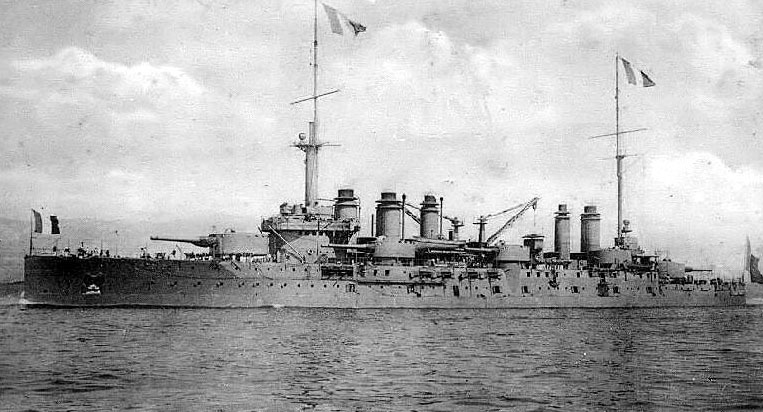

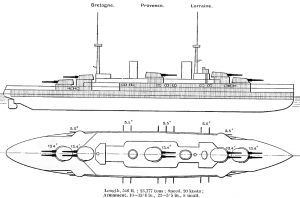

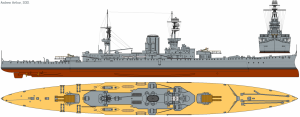

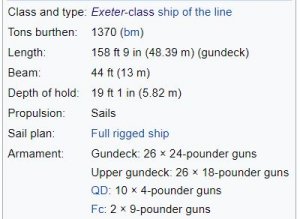

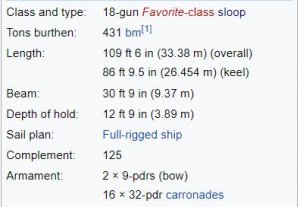

Design and description

Design and description

Although the

Danton-class battleships were a significant improvement from the preceding

Liberté class, they were outclassed by the advent of the

dreadnought well before they were completed. This, combined with other poor traits, including the great weight in coal they had to carry, made them unsuccessful ships overall, though their numerous rapid-firing guns were of some use in the Mediterranean.

Condorcet was 146.6 meters (481 ft 0 in)

long overall and had a

beam of 25.8 m (84 ft 8 in) and a full-load

draft of 9.2 m (30 ft 2 in). She displaced 19,736 metric tons (19,424 long tons) at

deep load and had a crew of 681 officers and enlisted men. The ship was powered by four

Parsons steam turbines using steam generated by twenty-six

Niclausse boilers. The turbines were rated at 22,500

shaft horsepower (16,800 kW) and provided a top speed of around 19

knots (35 km/h; 22 mph).

Condorcet reached a top speed of 19.7

knots (36.5 km/h; 22.7 mph) on her

sea trials. She carried a maximum of 2,027 tonnes (1,995 long tons) of coal which allowed her to steam for 3,370 miles (2,930 nmi) at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).

Condorcet's main battery consisted of four

305mm/45 Modèle 1906 guns mounted in two twin

gun turrets, one forward and one aft. The secondary battery consisted of twelve

240mm/50 Modèle 1902 guns in twin turrets, three on each side of the ship. A number of smaller guns were carried for defense against

torpedo boats. These included sixteen 75 mm (3.0 in) L/65 guns and ten

47-millimetre (1.9 in) Hotchkiss guns. The ship was also armed with two submerged 450 mm (17.7 in)

torpedo tubes. The ship's

main belt was 270 mm (10.6 in) thick and the main battery was protected by up to 300 mm (11.8 in) of armor. The

conning tower also had 300 mm thick sides.

Wartime modifications

During the war 75 mm anti-aircraft guns were installed on the roofs of the ship's two forward 240 mm gun turrets.

[3] During 1918, the mainmast was shortened to allow the ship to fly a captive

kite balloon and the elevation of the 240 mm guns was increased which extended their range to 18,000 meters (20,000 yd).

[1]

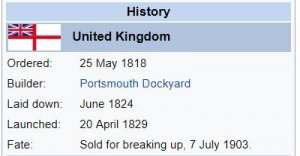

Career

Construction of

Condorcet was begun on 26 December 1906 by

Ateliers et Chantiers de la Loire in

Saint-Nazaire and the ship was

laid down on 23 August 1907. She was

launched on 20 April 1909 and was completed on 25 July 1911.

Condorcet was initially assigned to the 1st Division of the 1st Squadron (

escadre) of the Mediterranean Fleet when she was commissioned. The ship participated in combined fleet maneuvers between

Provence and

Tunisia in May–June 1913 and the subsequent

naval review conducted by the

President of France,

Raymond Poincaré on 7 June 1913. Afterwards,

Condorcet joined her squadron in its tour of the Eastern Mediterranean in October–December 1913 and participated in the grand fleet exercise in the Mediterranean in May 1914.

World War I

At the beginning of the war, the ship, together with her

sister Vergniaud and the dreadnought

Courbet, unsuccessfully searched for the German battlecruiser

Goeben and the light cruiser

Breslau in the

Balearic Islands. On 9 August,

Condorcet cruised the

Strait of Sicily in an attempt to prevent the German ships from breaking out to the West. On 16 August 1914 the combined

Anglo-French Fleet under Admiral

Auguste Boué de Lapeyrère, including

Condorcet, made a sweep of the Adriatic Sea. The Allied ships encountered the Austro-Hungarian cruiser

SMS Zenta, escorted by the

destroyer SMS Ulan, blockading the coast of

Montenegro. There were too many ships for

Zenta to escape, so she remained behind to allow

Ulan to get away and was sunk by gunfire during the Battle of Antivari off the coast of

Bar, Montenegro.

Condorcet subsequently participated in a number of raids into the Adriatic later in the year and patrolled the

Ionian Islands. From December 1914 to 1916, the ship participated in the distant blockade of the Straits of Otranto while based in

Corfu. On 1 December 1916,

Condorcet was in

Athens and contributed troops to the

Allied attempt to ensure Greek acquiescence to

Allied operations in Macedonia. Shortly afterwards, she was transferred to

Mudros to prevent

Goeben from breaking out into the Mediterranean and remained there until September 1917. The ship was transferred to the 2nd Division of the 1st Squadron in May 1918 and returned to Mudros where she remained for the rest of the war.

Postwar career

From 6 December 1918 to 2 March 1919,

Condorcet represented France in the Allied squadron in

Fiume that supervised the settlement of the

Yugoslav question. Afterwards, the ship was assigned to the Channel Division of the French Navy. She was modernized in 1923–24 to improve her underwater protection and her four aft 75 mm guns were removed. Together with her sisters

Diderot and

Voltaire, she was assigned to the Training Division at Toulon.

Condorcet housed the torpedo and electrical schools and had a torpedo tube fitted on the port side of her

quarterdeck. She was partially disarmed in 1931 and converted into an accommodation hulk; by 1939 her propellers had been removed. The famous underwater explorer

Jacques Cousteau began

diving while stationed aboard the ship in 1936.

In April 1941, the ship was towed to sea to evaluate the propellant used by the battleship

Richelieu during the

Battle of Dakar on 24 September 1940. One 38-centimetre (15 in) gun had an explosion in the breech and the propellant for the shell was thought to be the cause. A number of shots were successfully fired from

Condorcet's aft turret by remote control that exonerated the propellant. The following July, the ship was modified to house the signal, radio and electrician's schools. Berthing areas were installed in the bases of four funnels, which had been removed previously, and the latest radio equipment was installed for the students to train on. Later that year,

Condorcet was accidentally rammed by the

submarine Le Glorieux as she was leaving

drydock. The impact punctured the ship's hull and flooded one compartment which required

Condorcet to be drydocked for repairs. The ship was captured intact by the Germans when they occupied Vichy France on 27 November 1942. Unlike the bulk of the

French Fleet in Toulon,

Condorcet was not

scuttled because she had trainees aboard. Used by the Germans as a barracks ship, she was badly damaged by

Allied aircraft in August 1944 and scuttled that same month by the Germans.

Some of her 240 mm guns were used by the Germans in a coastal battery on the north bank of the Gironde estuary on the Bay of Biscay in 1944.

The ship was salvaged in September 1945 and listed for sale on 14 December.

Condorcet's breaking up was completed about 1949.

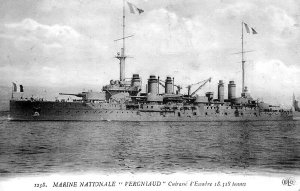

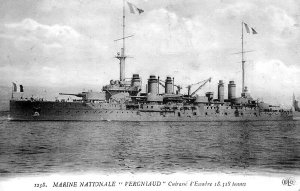

The

Danton-class battleship was a

class of six

pre-dreadnought battleships built for the

French Navy (

Marine Nationale) before

World War I. The ships were assigned to the

Mediterranean Fleet after

commissioning in 1911. After the beginning of World War I in early August 1914, five of the

sister shipsparticipated in the

Battle of Antivari. They spent most of the rest of the war

blockading the

Straits of Otranto and the

Dardanelles to prevent warships of the

Central Powers from breaking out into the Mediterranean. One ship was sunk by a German submarine in 1917.

The remaining five ships were obsolescent by the end of the war and most were assigned to secondary roles. Two of the sisters were sent to the Black Sea to support the

Whites during the

Russian Civil War. One ship

ran aground and the crew of the other

mutinied after one of its members was killed during a protest against intervention in support of the

Whites. Both ships were quickly condemned and later sold for

scrap. The remaining three sisters received partial modernizations in the mid-1920s and became

training ships until they were condemned in the mid-1930s and later scrapped. The only survivor still afloat at the beginning of World War II in August 1939 had been

hulked in 1931 and was serving as part of the navy's torpedo school. She was captured by the Germans when they

occupied Vichy France in 1942 and

scuttled by them after the

Allied invasion of southern France in 1944.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_battleship_Condorcet

en.wikipedia.org