Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

23 April 1791 – Launch of HMS Providence, a sloop of the Royal Navy, famous for being commanded by William Bligh on his second breadfruit voyage between 1791 and 1794

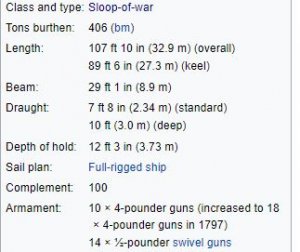

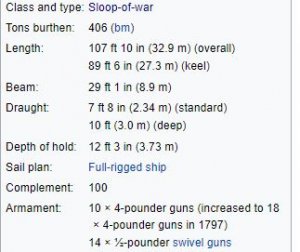

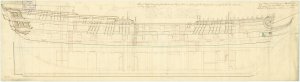

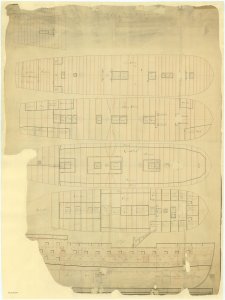

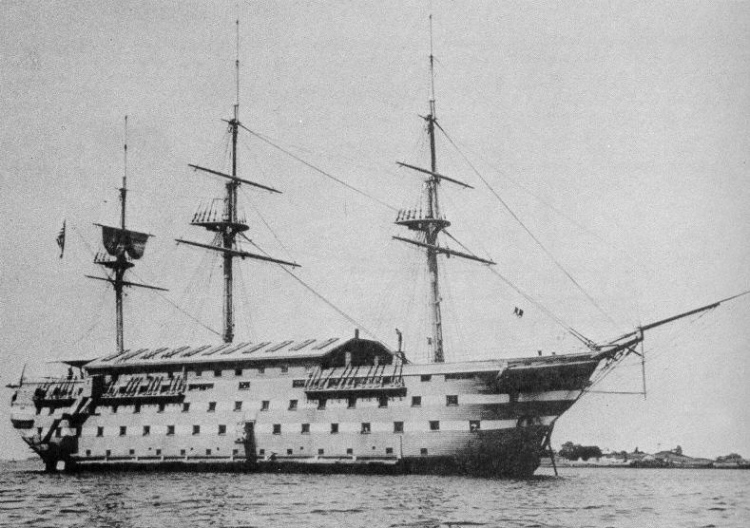

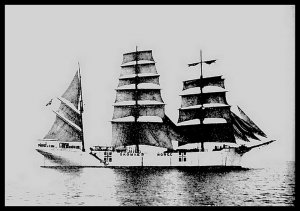

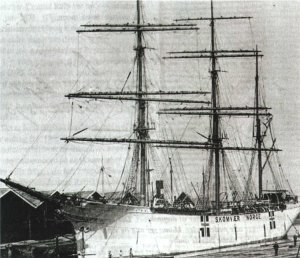

HMS Providence was a sloop of the Royal Navy, famous for being commanded by William Bligh on his second breadfruit voyage between 1791 and 1794.

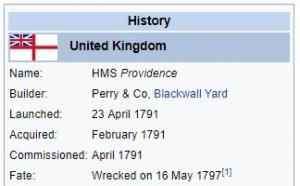

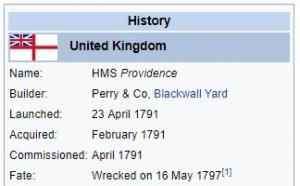

The Admiralty purchased Providence on the stocks from Perry & Co, Blackwall Yard in February 1791. She was launched on 23 April 1791 and commissioned under Bligh that month. She was coppered at Woolwich for the sum of £1,267, and then again at Deptford for £3,981.

Second Breadfruit Voyage

Rated as a sixth rate, she sailed for the Pacific on 2 August 1791 on Bligh's Second Breadfruit Voyage. Bligh completed a mission to collect breadfruit trees and other botanical specimens from the Pacific, which he transported to the West Indies. Specimens were given to the Royal Botanic Gardens in St. Vincent. Providence returned to Britain in August 1793, having been re-rated as a sloop on 30 September 1793.

Vancouver Expedition

She underwent another refit at Woolwich and was recommissioned in October 1793 under the command of Commander William Robert Broughton. Broughton was ordered to rejoin the Vancouver Expedition and departed Britain on 15 February 1795. Reaching Monterrey long after the expedition made its final departure, Broughton decided (correctly) that Vancouver would not have left his surveying task unfinished and departed to chart the coast of east Asia.

In the course of his explorations, he named Caroline Island Carolina (which later became "Caroline") "in compliment to the daughter of Sir Philip Stephens of the Admiralty." This name superseded that given by Pedro Fernández de Quirós, a Portuguese explorer sailing on behalf of Spain; his account names the island "San Bernardo."

Providence voyaged to Asia as the crew surveyed the coast of Hokkaidō before wintering at Macau. There Broughton purchased a small schooner which proved providential when, on 16 May 1797 Providence was wrecked when she struck a coral reef at Miyako-jima, south of Okinawa. The wreck is described by the Ship's Astronomer John Crosley in a passage copied from the ship's log book. Broughton and his crew continued the mission in the schooner, exploring northeast Asia, and returned home in February 1799

An idealized print of the imagined circumstances of the foundation of Sydney in 1789, with the town already established in the background. It lays emphasis on the natural resources of the land and its amenability to rearing European stock; the directive role of the Navy and military personnel involved; the presence of a gentlemanly civilian element among early arrivals (the man shooting on the left); British dominance over the Abroriginal population and the convict-colonists, with the latter being reformed by the redemptive qualities of labour. Gosse did a similar print, apparently as a pair to this and dated 1796, commemorating William Bligh's 'Transplanting of the Bread-Fruit Trees from Otaheite'. This shows the plants being loaded there into a boat and probably alludes to his second voyage in the 'Providence' and 'Assistant' (1791-93), which successfully took the plants to the West Indies, rather than the previous 'Bounty' voyage which ended in the mutiny of 1789

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

23 April 1791 – Launch of HMS Providence, a sloop of the Royal Navy, famous for being commanded by William Bligh on his second breadfruit voyage between 1791 and 1794

HMS Providence was a sloop of the Royal Navy, famous for being commanded by William Bligh on his second breadfruit voyage between 1791 and 1794.

The Admiralty purchased Providence on the stocks from Perry & Co, Blackwall Yard in February 1791. She was launched on 23 April 1791 and commissioned under Bligh that month. She was coppered at Woolwich for the sum of £1,267, and then again at Deptford for £3,981.

Second Breadfruit Voyage

Rated as a sixth rate, she sailed for the Pacific on 2 August 1791 on Bligh's Second Breadfruit Voyage. Bligh completed a mission to collect breadfruit trees and other botanical specimens from the Pacific, which he transported to the West Indies. Specimens were given to the Royal Botanic Gardens in St. Vincent. Providence returned to Britain in August 1793, having been re-rated as a sloop on 30 September 1793.

Vancouver Expedition

She underwent another refit at Woolwich and was recommissioned in October 1793 under the command of Commander William Robert Broughton. Broughton was ordered to rejoin the Vancouver Expedition and departed Britain on 15 February 1795. Reaching Monterrey long after the expedition made its final departure, Broughton decided (correctly) that Vancouver would not have left his surveying task unfinished and departed to chart the coast of east Asia.

In the course of his explorations, he named Caroline Island Carolina (which later became "Caroline") "in compliment to the daughter of Sir Philip Stephens of the Admiralty." This name superseded that given by Pedro Fernández de Quirós, a Portuguese explorer sailing on behalf of Spain; his account names the island "San Bernardo."

Providence voyaged to Asia as the crew surveyed the coast of Hokkaidō before wintering at Macau. There Broughton purchased a small schooner which proved providential when, on 16 May 1797 Providence was wrecked when she struck a coral reef at Miyako-jima, south of Okinawa. The wreck is described by the Ship's Astronomer John Crosley in a passage copied from the ship's log book. Broughton and his crew continued the mission in the schooner, exploring northeast Asia, and returned home in February 1799

An idealized print of the imagined circumstances of the foundation of Sydney in 1789, with the town already established in the background. It lays emphasis on the natural resources of the land and its amenability to rearing European stock; the directive role of the Navy and military personnel involved; the presence of a gentlemanly civilian element among early arrivals (the man shooting on the left); British dominance over the Abroriginal population and the convict-colonists, with the latter being reformed by the redemptive qualities of labour. Gosse did a similar print, apparently as a pair to this and dated 1796, commemorating William Bligh's 'Transplanting of the Bread-Fruit Trees from Otaheite'. This shows the plants being loaded there into a boat and probably alludes to his second voyage in the 'Providence' and 'Assistant' (1791-93), which successfully took the plants to the West Indies, rather than the previous 'Bounty' voyage which ended in the mutiny of 1789

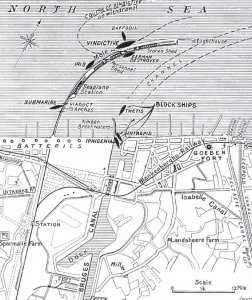

of the raid was skilfully exploited to raise Allied morale and to foreshadow victory Possunt quia posse videntur ("They can because they think they can"). Bacon wrote in 1931 that he was a seagoing commander with intimate knowledge of the tidal and navigational conditions in the Ostend and Zeebrugge areas; operational failures were due in part to the appointment of Keyes (an Admiralty man) and his changes to plans Bacon had laid.

of the raid was skilfully exploited to raise Allied morale and to foreshadow victory Possunt quia posse videntur ("They can because they think they can"). Bacon wrote in 1931 that he was a seagoing commander with intimate knowledge of the tidal and navigational conditions in the Ostend and Zeebrugge areas; operational failures were due in part to the appointment of Keyes (an Admiralty man) and his changes to plans Bacon had laid.