I am fairly new to the hobby. I have one completed build and two in process.

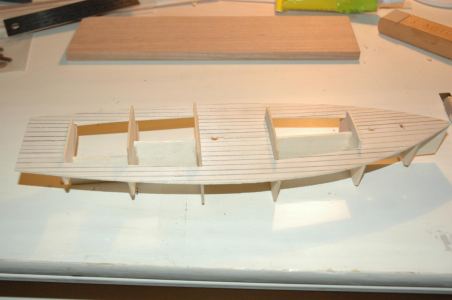

I am currently on the Model Shipways Sharpie Schooner. An older model, apparently, that instructs the builder to simply draw in parallel lines to represent the decking. I have done that, and it looks okay. As an early step in this journey I can live with this.

I have a stack of kits in the long term queue that, for the most part, include individual deck planks. Since getting interested in this hobby I have seen numerous techniques regarding the marking and installation of deck planking: from pencil marks to represent plank ends and nails, to holes drilled and filled with dark filler, to actual wooden plugs. I expect to try all at one point or another.

I am under no illusion that we are simply building recreations of actual, or suspected, designs of ships. As such, detail can only go so far, depending on scale and nature of the model. However, as a former theatrical set designer and builder, I am very much into the verisimilitude that goes with building representations of real life things.

So, to the point. In perusing the instructions for a number of my kits I am reading different approaches to representing the details in deck planking. Ignoring caulking in this post, I want to focus on deck 'nails', which I assume are wooden nails/plugs.

Lastly, glues.

The two predominant glues I see being used for decking are PVA and contact cement (sometimes referred to as shoemakers glue, or is that different than regular contact cement). After typing this I just recalled a build log that used Titebond Hide Glue. Thoughts?

My main question has to do with the qualities of each glue, the pros and cons. Do builders generally prefer one over the other, or does it depend on the project?

Many thanks

Cheers

I am currently on the Model Shipways Sharpie Schooner. An older model, apparently, that instructs the builder to simply draw in parallel lines to represent the decking. I have done that, and it looks okay. As an early step in this journey I can live with this.

I have a stack of kits in the long term queue that, for the most part, include individual deck planks. Since getting interested in this hobby I have seen numerous techniques regarding the marking and installation of deck planking: from pencil marks to represent plank ends and nails, to holes drilled and filled with dark filler, to actual wooden plugs. I expect to try all at one point or another.

I am under no illusion that we are simply building recreations of actual, or suspected, designs of ships. As such, detail can only go so far, depending on scale and nature of the model. However, as a former theatrical set designer and builder, I am very much into the verisimilitude that goes with building representations of real life things.

So, to the point. In perusing the instructions for a number of my kits I am reading different approaches to representing the details in deck planking. Ignoring caulking in this post, I want to focus on deck 'nails', which I assume are wooden nails/plugs.

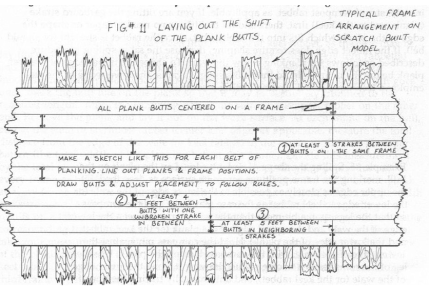

- Some instructions have plank ends drawn in, rather than planks cut to length, and do not include nails.

- Some show nails at plank ends, whether full length or cut.

- Some show nails at cut ends as well as where the planks cross the deck timbers.

Lastly, glues.

The two predominant glues I see being used for decking are PVA and contact cement (sometimes referred to as shoemakers glue, or is that different than regular contact cement). After typing this I just recalled a build log that used Titebond Hide Glue. Thoughts?

My main question has to do with the qualities of each glue, the pros and cons. Do builders generally prefer one over the other, or does it depend on the project?

Many thanks

Cheers