.

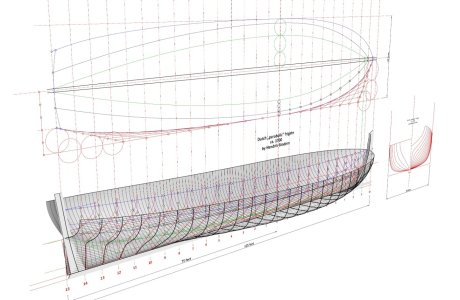

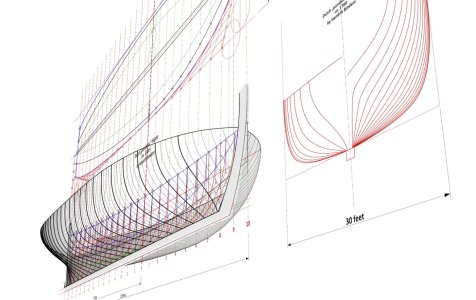

Among all previous presentations in this field, the content of this thread in particular can be seen as a kind of rehabilitation of those early modern Dutch shipbuilders who, according to rumours fabricated in modern times and widely disseminated by academics and other authors, were so geometrically challenged that they were only capable of shaping ship hulls ‘by eye’, and in combination with some rules of thumb that were not very clearly related to this particular aspect of design.

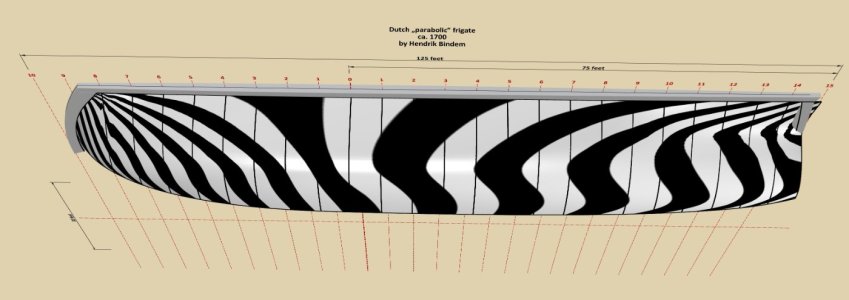

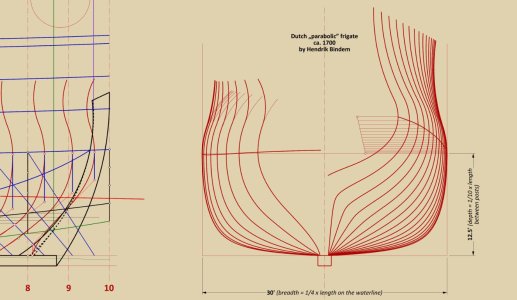

In fact, as will be shown later, they were at least several decades ahead of the famous ship designer Fredrik Henrik af Chapman in the wide application of ‘parabolically’ constructed entities in ship design, which today is commonly attributed only to the Swedish designer. Therefore, if anyone is to be blamed for geometric indolence, it is not the early modern Dutch shipwrights, but those who today deny them such abilities, perhaps due to their own incompetence in this field.

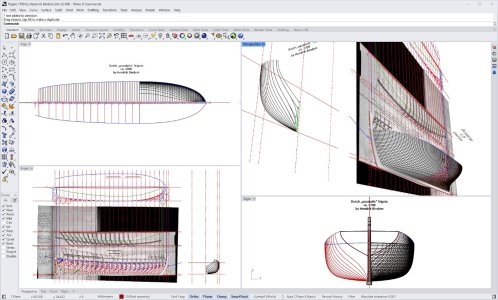

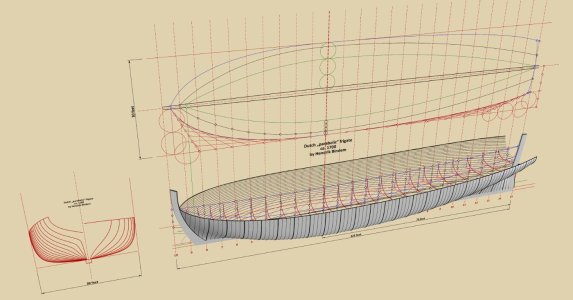

The design in question is found in papers collected by the Russian ruler Peter I, or at least during his reign and on his initiative, so it can be dated with reasonable certainty to the turn of the 17th and 18th centuries. The drawing is accompanied by a very sparse and rather deliberately vague and mysterious text description in Dutch, which, quite tellingly, also includes a statement that the way of designing this frigate can be explained verbally (most likely to Peter himself). Despite this cryptic statement by Hendrik Bindem, the use of ‘reverse engineering’ has made it possible to reconstruct the design method he employed, and it must be said that it is astonishing in its sophistication for that early period, or perhaps even more so in the modernity of its engineering approach to ship design!

Although Witsen, a humanist, was actually shown the ship plans and perhaps even had an attempt made to explain the design process to him, he ultimately gave up trying to understand the issue and, as a result, was unable to include an appropriate account in his 1671 publication, limiting himself to merely a very rudimentary comment on this particular aspect, and what is more, perhaps even partially outdated in technical terms already at the time of publication of his ‘Aeloude en Hedendaegsche Scheeps-bouw en Bestier’ (‘Ancient and Modern Shipbuilding and Management’), focusing instead on carpentry and historical issues, which were apparently easier for him to understand.

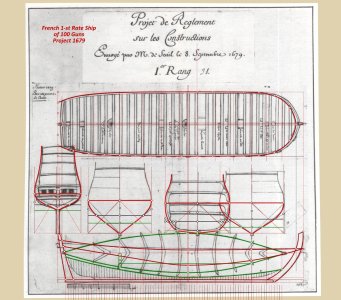

Similarly, ship carpenter van Yk left rather residual clues as to what ship architecture at his time actually was, which is not surprising considering that the vast majority of ship carpenters did not participate in the ship design process and had no real need to be fluent with such issues. However, he must have known that ships were routinely designed before their actual construction, since already in the preface to his work he refers on this matter to the French publication from 1677 by Dassié, L'architecture navale. In addition, evidence of proper design, albeit conveyed indirectly or fragmentarily, can be found later in his work, including in the content of actual shipbuilding contracts he cites.

Returning to Bindem's frigate and the accompanying restrictive statement by the Dutch shipwright about the oral transmission of design secrets, these must ultimately have been revealed to Peter in one way or another, since the collection of ship plans drawn up personally by the Russian ruler also includes designs of vessels using Dutch design methods (which in turn fit into the general paradigms of the Northern tradition of ship design), alongside those in the English and French (or more precisely: diagonal) fashion.

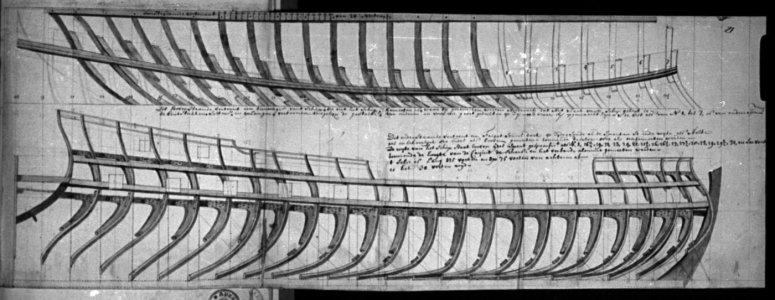

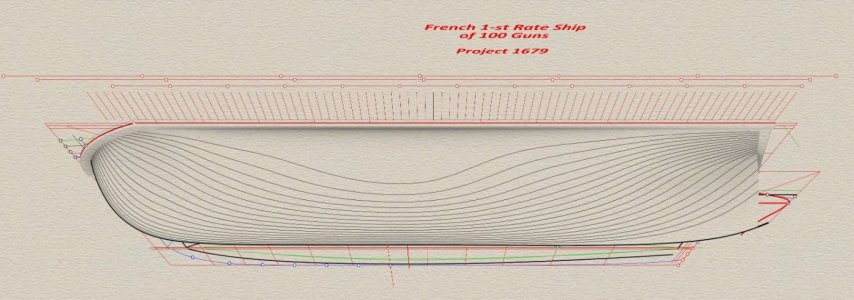

So much for the introduction, and below is a copy of the discussed frigate design by Hendrik Bindem (Russian archives).

.

Last edited: