.

This post is particularly difficult, for several reasons. Anyway...

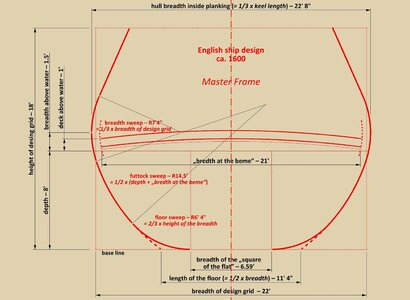

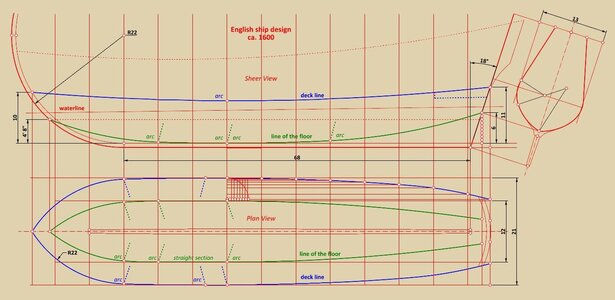

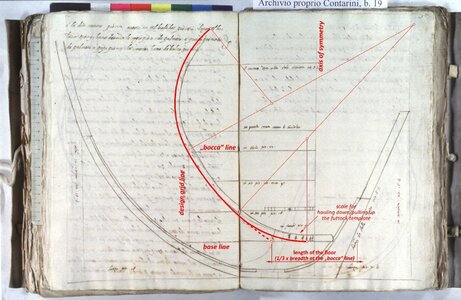

It is only now that the concept of the ca. 1600 ship plan has been read, that it is possible to attempt a realistic reconstruction of the shape of the entire hull. The peculiarities of the Mediterranean method inevitably require the inclusion of later treatments of an already non-graphic nature, practically applied during the actual construction of the ship in real size. The point is that the established shape of the master frame (in the sketch or even in the designer's imagination), served primarily to prepare the wooden templates in natural scale, and these in turn to determine the contours of the other frames. Such a state of affairs had momentous conceptual consequences, as it limited the individual curvatures of the frames thus 'reduced' to fixed radii and, as a further consequence, could normally only be used for the central part of the ship's hull (the two ends of the hull had already been shaped more or less empirically with ribbands or battens).

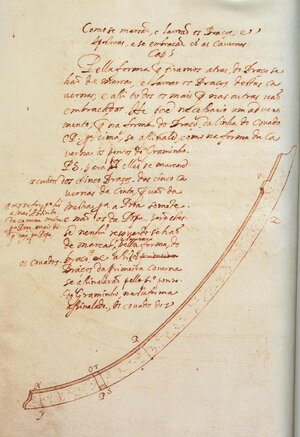

The Mediterranean method is not homogeneous and can have many variations. It is best to use the sources (particularly useful are e.g. Trombetta 1445, de Nicolò 1550, Oliveira 1580, Lavanha 1608–1615, Fernandez 1616, Dudley 1646), and if they prove too hermetic, a good alternative are the excellent modern studies, particularly relevant in this case, e.g. by Sergio Bellabarba, Jean Boudriot, Éric Rieth, Filipe Castro and Taras Pevny. The latter, in particular, has recently made an attempts to scientifically revise already too long-repeated false stereotypes concerning the shipbuilding practices in early modern England.

As far as the English manuscript sources from this period are concerned, Mathew Baker's manuscript from the late 16th century is expected to be the most relevant, unfortunately, however, it is guarded almost like a top state secret and, as a result, virtually inaccessible. The so-called Newton/Scott manuscripts, apparently incorrectly dated by today's scholars (should be a couple of decades later than ca. 1600), are of little help in this case. Nevertheless, an anonymous manuscript from 1620–1625 (the so-called Salisbury manuscript), while already describing new, emerging practices specific to the English school, still uses important elements of a conceptual nature inherited from hitherto Mediterranean practices. It has to be said that this results in a certain design schizophrenia in places, but it is precisely this state of affairs that provides an excellent explanation for the so far unclear chronology of the development of naval architecture in early modern England.

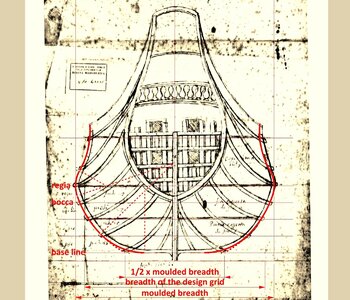

For the reconstruction of the hull shape, I finally decided to use the Venetian 'partisone' method, due to the numerous historically, archaeologically (eg.

Mary Rose) and scripturally (eg. Baker's

Fragments...) confirmed instances of this particular Mediterranean method being used in England. The essence of this method is the sliding of the futtock template along the bilge/floor curve, and the value of this rotation is limited by the breadth of the hull at the „bocca” level (also indicated as „deck line” or „breadth at the beam” in previous diagrams); an alternative is the simple tilting of the futtock template. The configuration of the wooden templates, on the other hand, was taken from the Salisbury manuscript.

The geometric transformations applied here mean that it would not be possible to align the frame templates to the „bocca” point and at the same time to the point of the actual greatest breadth of the hull while maintaining the tangency of the individual templates, unless one increases the number of templates involved and at the same time carries out prior calculations, which are in fact completely unnecessary for this variant, and the time-consuming and complexity of which would be no small challenge even today. It so happens that on the analysed plan of c. 1600, only the „bocca” line is defined, and by selecting the templates in the configuration shown in the diagram below (i.e. of just three components), the greatest breadth of the hull (actual) is shaped „automatically”.

Note: the design of the ca. 1600 ship features an anomaly – the „bocca” line should normally be placed at or below the junction of the breadth sweep and the futtock sweep for the geometry to work perfectly. However, this anomaly is small enough to have significant consequences.

.