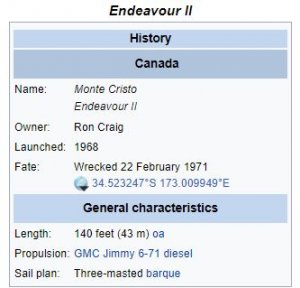

Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

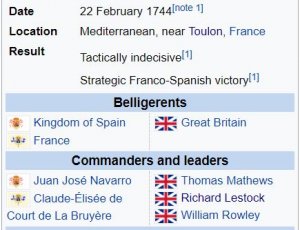

22 February 1744 - Battle of Toulon or Battle of Cape Sicié - Part I

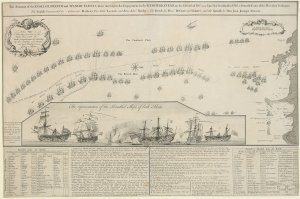

The naval Battle of Toulon or Battle of Cape Sicié took place on 22–23 February 1744 (NS) in the Mediterranean off the French coast near Toulon. A combined Franco-Spanish fleet fought off Britain's Mediterranean Fleet. The French fleet, not officially at war with Great Britain, only joined the fighting late, when it was clear that the greatly outnumbered Spanish fleet had gained the advantage over its foe. With the French intervention, the British fleet was forced to withdraw.

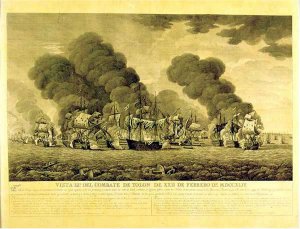

Engraving of the Battle (1796) Naval museum of Madrid.

In Britain the battle was regarded as the most mortifying defeat; the Franco-Spanish fleet successfully ended the British blockade and inflicted considerably more damage to the British than they received, causing the British to withdraw to Menorca in need of heavy repairs. The retreat of Admiral Mathews' fleet left the Mediterranean Sea temporarily under Spanish control, allowing the Spanish navy to deliver troops and supplies to the Spanish army in Italy, decisively swinging the war there in their favour.

Thomas Mathews was tried by court-martial in 1746 on charges of having brought the fleet into action in a disorganised manner, of having fled the enemy, and of having failed to bring the enemy to action when the conditions were advantageous. He was one of seven ship captains dismissed from service.

In English-language literature the battle is viewed as indecisive at best and a fiasco at worst.

Prelude

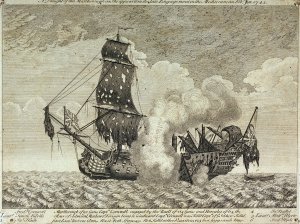

The British fire ship HMS Anne Galley, aflame and sinking short of her intended target, the Spanish flagship Real Felipe

The War of the Austrian Succession broke out in 1740, over whether Maria Theresa could inherit the throne of Hapsburg Austria. Britain supported Austria and the claim of Maria Theresa, whilst Spain and France supported the rival claim of Charles, Elector of Bavaria. Britain and Spain had been at war in the Americas since 1739, in the War of Jenkins' Ear. Britain and France were not officially at war at the start of 1744, although they were on opposite sides of the wider conflict and France was secretly planning an invasion of Britain.

Thomas Mathews had had a solid but unspectacular career as a naval captain, rising to command a small squadron before retiring from the navy in 1724. He returned to naval service in 1736, but only in a shore-based administrative role. The outbreak of war with Spain and the imminent threat of war with France led to Mathews' return to active service after years of effective retirement, with a promotion directly to Vice-Admiral of the Red on 13 March 1741. He was given command of a fleet in the Mediterranean, and with it an appointment as plenipotentiary to Charles Emmanuel III, King of Sardinia (who supported Maria Theresa's claim), and the other courts of Italy. The choice of Mathews for the role was somewhat unexpected, as he was not especially distinguished, and had not served in the navy for a number of years.

The second in command in the Mediterranean was Rear-Admiral Richard Lestock. Mathews knew Lestock from their time at Chatham Dockyard, when Mathews had been the Commissioner and Lestock had commanded the guard ships stationed in the Medway. The two had not been on good terms, and Lestock had hoped to receive the command of the Mediterranean fleet himself – he had been acting commander for several weeks after Nicholas Haddock was recalled. On receiving the Mediterranean posting, Mathews requested that Lestock be recalled to Britain. Lestock also asked to be reassigned, requesting the command of the West Indies fleet instead. The Admiralty declined to act upon either request.

The two men continued their disagreements during their time in the Mediterranean, although Mathews' preoccupation with his diplomatic duties meant they did not break out into open argument. In 1742 Mathews sent a small squadron to Naples to compel King Charles, later the King of Spain, to remain neutral in the war. It was commanded by Commodore William Martin, who refused to enter into negotiations, and gave the king half an hour in which to return an answer. The Neapolitans were forced to agree to the British demands.

In June 1742 a squadron of Spanish galleys, which had taken refuge in the Bay of Saint-Tropez, was burnt by the fire ships of Mathews' fleet. In the meantime a Spanish squadron had taken refuge in Toulon, and was watched by the British fleet from Hyères. The British began a naval blockade outside Toulon, allowing French vessels to pass but preventing the Spanish from leaving.

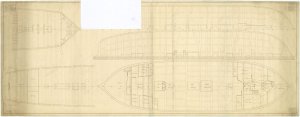

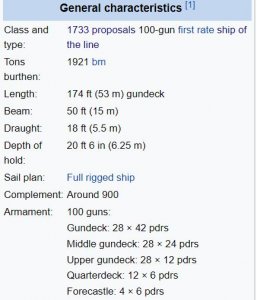

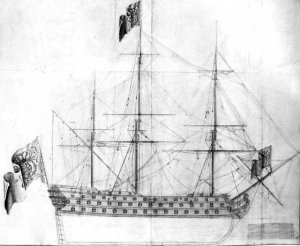

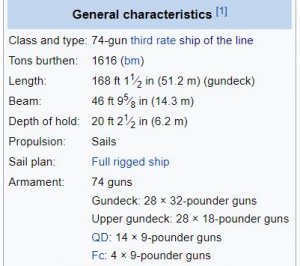

Plano del navío Real Felipe, de 114 cañones, aunque en la batalla llevaba 112.

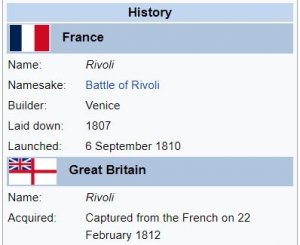

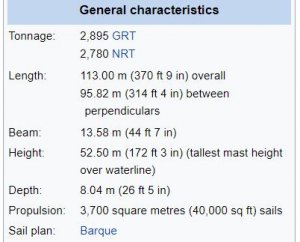

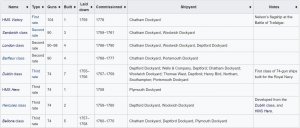

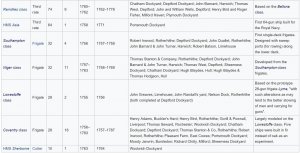

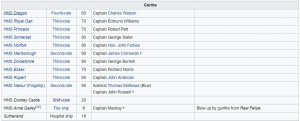

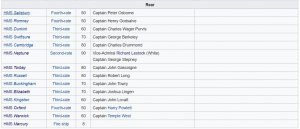

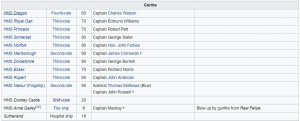

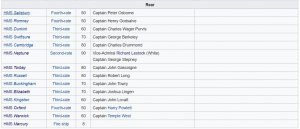

Order of battle

The Spanish ship Poder being unable to keep up with the British ships that captured her, was rataken in the night by the French squadron. The French perceiving the British fleet coming fall up with them, cast off and abandoned the Poder, first setting fire to her, and she shortly after blew up.

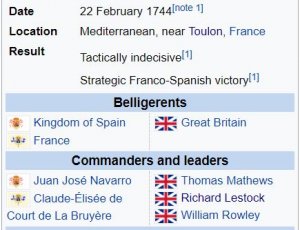

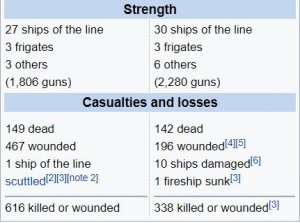

According a spanish web page the spanish french fleet had 1.806 guns available with 19.100 seamen.

On british side 16.585 seamen fighted with 2.280 guns.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Toulon_(1744)

22 February 1744 - Battle of Toulon or Battle of Cape Sicié - Part I

The naval Battle of Toulon or Battle of Cape Sicié took place on 22–23 February 1744 (NS) in the Mediterranean off the French coast near Toulon. A combined Franco-Spanish fleet fought off Britain's Mediterranean Fleet. The French fleet, not officially at war with Great Britain, only joined the fighting late, when it was clear that the greatly outnumbered Spanish fleet had gained the advantage over its foe. With the French intervention, the British fleet was forced to withdraw.

Engraving of the Battle (1796) Naval museum of Madrid.

In Britain the battle was regarded as the most mortifying defeat; the Franco-Spanish fleet successfully ended the British blockade and inflicted considerably more damage to the British than they received, causing the British to withdraw to Menorca in need of heavy repairs. The retreat of Admiral Mathews' fleet left the Mediterranean Sea temporarily under Spanish control, allowing the Spanish navy to deliver troops and supplies to the Spanish army in Italy, decisively swinging the war there in their favour.

Thomas Mathews was tried by court-martial in 1746 on charges of having brought the fleet into action in a disorganised manner, of having fled the enemy, and of having failed to bring the enemy to action when the conditions were advantageous. He was one of seven ship captains dismissed from service.

In English-language literature the battle is viewed as indecisive at best and a fiasco at worst.

Prelude

The British fire ship HMS Anne Galley, aflame and sinking short of her intended target, the Spanish flagship Real Felipe

The War of the Austrian Succession broke out in 1740, over whether Maria Theresa could inherit the throne of Hapsburg Austria. Britain supported Austria and the claim of Maria Theresa, whilst Spain and France supported the rival claim of Charles, Elector of Bavaria. Britain and Spain had been at war in the Americas since 1739, in the War of Jenkins' Ear. Britain and France were not officially at war at the start of 1744, although they were on opposite sides of the wider conflict and France was secretly planning an invasion of Britain.

Thomas Mathews had had a solid but unspectacular career as a naval captain, rising to command a small squadron before retiring from the navy in 1724. He returned to naval service in 1736, but only in a shore-based administrative role. The outbreak of war with Spain and the imminent threat of war with France led to Mathews' return to active service after years of effective retirement, with a promotion directly to Vice-Admiral of the Red on 13 March 1741. He was given command of a fleet in the Mediterranean, and with it an appointment as plenipotentiary to Charles Emmanuel III, King of Sardinia (who supported Maria Theresa's claim), and the other courts of Italy. The choice of Mathews for the role was somewhat unexpected, as he was not especially distinguished, and had not served in the navy for a number of years.

The second in command in the Mediterranean was Rear-Admiral Richard Lestock. Mathews knew Lestock from their time at Chatham Dockyard, when Mathews had been the Commissioner and Lestock had commanded the guard ships stationed in the Medway. The two had not been on good terms, and Lestock had hoped to receive the command of the Mediterranean fleet himself – he had been acting commander for several weeks after Nicholas Haddock was recalled. On receiving the Mediterranean posting, Mathews requested that Lestock be recalled to Britain. Lestock also asked to be reassigned, requesting the command of the West Indies fleet instead. The Admiralty declined to act upon either request.

The two men continued their disagreements during their time in the Mediterranean, although Mathews' preoccupation with his diplomatic duties meant they did not break out into open argument. In 1742 Mathews sent a small squadron to Naples to compel King Charles, later the King of Spain, to remain neutral in the war. It was commanded by Commodore William Martin, who refused to enter into negotiations, and gave the king half an hour in which to return an answer. The Neapolitans were forced to agree to the British demands.

In June 1742 a squadron of Spanish galleys, which had taken refuge in the Bay of Saint-Tropez, was burnt by the fire ships of Mathews' fleet. In the meantime a Spanish squadron had taken refuge in Toulon, and was watched by the British fleet from Hyères. The British began a naval blockade outside Toulon, allowing French vessels to pass but preventing the Spanish from leaving.

Plano del navío Real Felipe, de 114 cañones, aunque en la batalla llevaba 112.

Order of battle

The Spanish ship Poder being unable to keep up with the British ships that captured her, was rataken in the night by the French squadron. The French perceiving the British fleet coming fall up with them, cast off and abandoned the Poder, first setting fire to her, and she shortly after blew up.

According a spanish web page the spanish french fleet had 1.806 guns available with 19.100 seamen.

On british side 16.585 seamen fighted with 2.280 guns.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Toulon_(1744)

Last edited:

and Hurt Board

and Hurt Board