- Joined

- Jun 29, 2024

- Messages

- 1,519

- Points

- 438

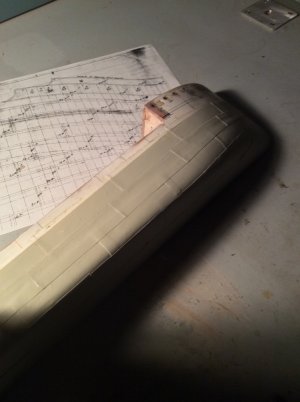

This is a continuance of a Build Log currently “stranded” on MSW. My intent is to quickly review progress to date and to then proceed with the build as progress goes forward. Readers wishing a more detailed discussion of previous work will find it on MSW ( Scratch Built Models 1900 and later.

History

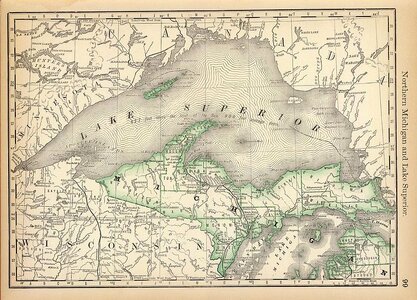

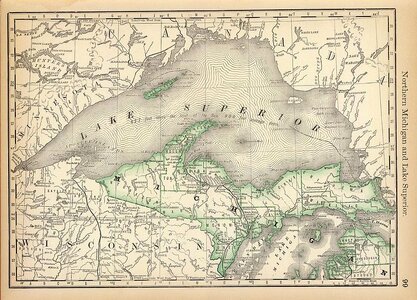

Lake Superior is by far the largest of North America’s Great Lakes, the five beautiful interconnected bodies of water that stretch through America’s Heartland. The four “upper” lakes; Erie, Huron, Michigan, and Superior, have long been used to transport vast cargos of steel making ingredients, iron ore, and limestone from mines in northern Minnesota and Michigan to steel mills in Chicago, Ohio, and Pittsburgh.

The lakes are freshwater that often freezes during the region’s bitter cold winters so throughout much of the Twentieth Century the shipping season began in late March and ended in December. Most of the time, the lakes do not have the large swells typical of the world’s oceans, but violent storms can occur particularly when the seasons change in the spring and fall. Also, unlike saltwater seas heavy coatings of ice can build up on topside surfaces. Relative to the oceans the lakes’ smaller size means that vessels can run out of “sea room” impaling thems on rocky shores.

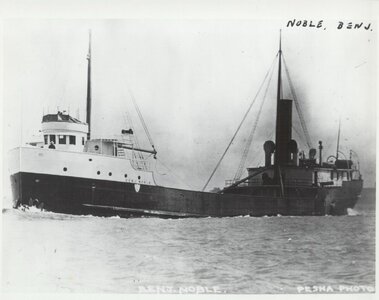

It was during such a storm that young Captain John Eisenhardt master of the 250ft long steamship Benjamin Noble found himself in the early hours of April 28, 1914 with a badly overloaded vessel. He had assumed command of the ship at Conneaut, Ohio on Lake Erie when her regular master, watching her being loaded with a heavy cargo of railroad rails consigned to Duluth, Minnesota at the extreme western end of Lake Superior, refused to take her out.

She almost made it, traveling across Lakes Erie and Huron, through the Soo Canal. On Lake Superior she emerged from behind the famous Apostle Islands into the funnel shape Western arm of the Lake. Having sailed this stretch of the lake, under normal conditions it is an easy trip; due west, deep water, and no navigational hazards. Unfortunately, however, only the very small port of Two Harbors offers any sort of refuge over this final stretch of lake and conditions were anything but normal. There is evidence that the Noble made it to Knife River only 20 miles from Duluth. By then, Captain Eisenhardt apparently found it necessary to seek shelter at Two Harbors Six Miles away but after turning back to the Northeast, the Benjamin Noble suddenly plunged to the bottom of the lake taking her entire 20+ crew with her. Despite efforts to find her and her crew, she was not discovered until 2005, 89 years later. The wreck divers who found her have filmed the wreckage and registered her on the National Register of Historic Places. They hope that the wreck’s deep location (300ft) will protect her from looters.

History

Lake Superior is by far the largest of North America’s Great Lakes, the five beautiful interconnected bodies of water that stretch through America’s Heartland. The four “upper” lakes; Erie, Huron, Michigan, and Superior, have long been used to transport vast cargos of steel making ingredients, iron ore, and limestone from mines in northern Minnesota and Michigan to steel mills in Chicago, Ohio, and Pittsburgh.

The lakes are freshwater that often freezes during the region’s bitter cold winters so throughout much of the Twentieth Century the shipping season began in late March and ended in December. Most of the time, the lakes do not have the large swells typical of the world’s oceans, but violent storms can occur particularly when the seasons change in the spring and fall. Also, unlike saltwater seas heavy coatings of ice can build up on topside surfaces. Relative to the oceans the lakes’ smaller size means that vessels can run out of “sea room” impaling thems on rocky shores.

It was during such a storm that young Captain John Eisenhardt master of the 250ft long steamship Benjamin Noble found himself in the early hours of April 28, 1914 with a badly overloaded vessel. He had assumed command of the ship at Conneaut, Ohio on Lake Erie when her regular master, watching her being loaded with a heavy cargo of railroad rails consigned to Duluth, Minnesota at the extreme western end of Lake Superior, refused to take her out.

She almost made it, traveling across Lakes Erie and Huron, through the Soo Canal. On Lake Superior she emerged from behind the famous Apostle Islands into the funnel shape Western arm of the Lake. Having sailed this stretch of the lake, under normal conditions it is an easy trip; due west, deep water, and no navigational hazards. Unfortunately, however, only the very small port of Two Harbors offers any sort of refuge over this final stretch of lake and conditions were anything but normal. There is evidence that the Noble made it to Knife River only 20 miles from Duluth. By then, Captain Eisenhardt apparently found it necessary to seek shelter at Two Harbors Six Miles away but after turning back to the Northeast, the Benjamin Noble suddenly plunged to the bottom of the lake taking her entire 20+ crew with her. Despite efforts to find her and her crew, she was not discovered until 2005, 89 years later. The wreck divers who found her have filmed the wreckage and registered her on the National Register of Historic Places. They hope that the wreck’s deep location (300ft) will protect her from looters.

Last edited by a moderator: