Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

24 December 1810 - Boats of HMS Diana (38), Capt. Charles Grant, took and burnt French frigate Elize ashore in the Baie de la Hougue

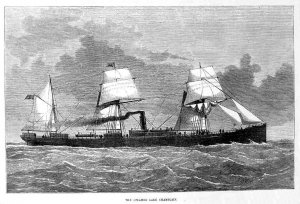

HMS Diana was a 38-gun Artois-class fifth rate frigate of the Royal Navy. She was launched in 1794.

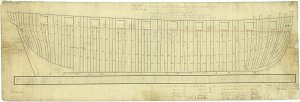

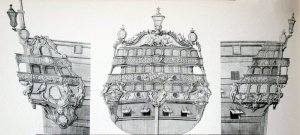

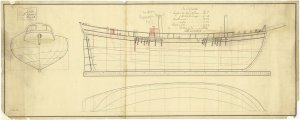

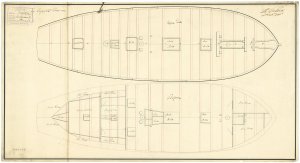

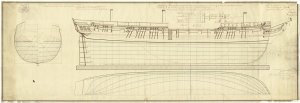

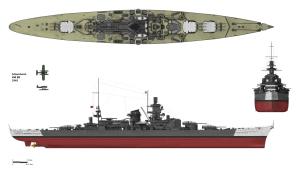

Scale: 1:48. A contemporary full hull model of the 'Diana'-class frigate (1794), a 38-gun fifth-rate, built in 'bread and butter' fashion and finished in the Georgian style. Model is partially decked, equipped, and mounted on its original pillar supports with a modern base. This model clearly illustrates the increasing use of bone and ivory in particular the carved decoration on the stern and the numerous fittings that were turned on a lathe such as the capstan head and deadeyes. This class of frigate were built from plans by Sir John Henslow, Surveyor of the Navy, 1784-1806, and had a gun deck of 146 feet by 39 feet in the beam and a tonnage of 984 (builders old measurement). Known as the 'eyes and ears’ of the fleet, the frigate was used for a variety of roles such as searching out and reporting on the enemy fleets and convoys, as well as independent patrols worldwide.

Type: 38-gun Artois-class fifth rate frigate

Tons burthen: 999 3⁄94 bm

Length:

Depth of hold: 13 ft 9 in (4.19 m)

Sail plan: Full-rigged ship

Complement: 270 (later 315)

Armament:

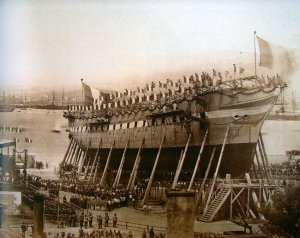

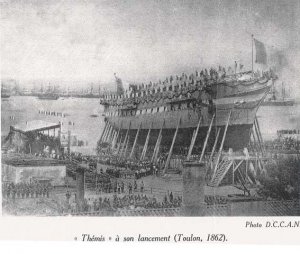

Scale: 1:48. A model of one of the nine ships of the 'Artois/Apollo' class of 38-gun frigates designed by Sir John Henslow and built between 1793 and 1795. Seven were built conventionally in private shipyards and two more were constructed experimentally in fir in the Royal Dockyards at Chatham and Woolwich. Four of the conventional ships were wrecked between 1797 and 1799, and the fir-built ships deteriorated rapidly. The model shows the hull of the ship fully planked and set on a launching cradle, though without the rails on which it will run, as is common on models of this period. The stern decoration and figurehead are carefully carved and some features such as decorations and the steering wheel are made in bone. The figurehead is of Diana the huntress, which identifies the ship. Two other models of this ship are in the Museum collection.

Because Diana served in the Royal Navy's Egyptian campaign between 8 March 1801 and 2 September, her officers and crew qualified for the clasp "Egypt" to the Naval General Service Medal that the Admiralty authorized in 1850 to all surviving claimants.

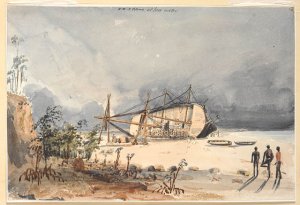

Diana participated in an attack on a French frigate squadron anchored at Saint-Vaast-la-Hougue at the Action of 15 November 1810, which ultimately led to the destruction of the Elisa. (Boats from Diana went in and set fire to the beached Eliza despite heavy fire from shore batteries and three nearby armed brigs; the British suffered no casualties.)

On 7 March 1815 Diana was sold to the Dutch navy for £36,796. On 27 August 1816 she was one of six Dutch frigates that participated in the bombardment of Algiers.

Fate

Diana was accidentally destroyed in a fire on 16 January 1839 while in dry-dock at Willemsoord, Den Helder.

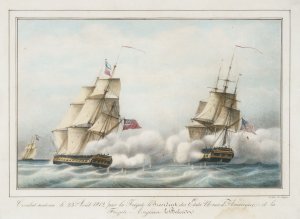

HMS Ethalion in action with the Spanish frigate Thetis off Cape Finisterre, 16 October 1799

The Artois class were a series of nine frigates built to a 1793 design by Sir John Henslow, which served in the Royal Navy during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars.

Seven of these ships were built by contract with commercial builders, while the remaining pair (Tamar and Clyde) were dockyard-built - the latter built using "fir" (pitch pine) instead of the normal oak.

They were armed with a main battery of 28 eighteen-pounder cannon on their upper deck, the main gun deck of a frigate. Besides this battery, they also carried two 9-pounders together with twelve 32-pounder carronades on the quarter deck, and another two 9-pounders together with two 32-pounder carronades on the forecastle.

Scale: approximately 1:32. According to the writing on the side of the hull, this model was made from part of the mainmast of the French flagship ‘L’Orient’ which blew up at the Battle of the Nile in 1798. The model is rather crudely made and its hull is not quite in the right proportions, being too deep, so it is probably sailor-made. The rigging appears to be contemporary. Marmaduke Stalkaart, who also wrote a textbook on naval architecture, built the ‘Seahorse’ (1794) at Rotherhithe on the Thames. It was one of the ‘Artois/Apollo’ class, of which several models exist. The ‘Seahorse’ was not actually present at the Battle of the Nile, but joined Nelson’s fleet soon afterwards.

Ships in class

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Diana_(1794)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artois-class_frigate

24 December 1810 - Boats of HMS Diana (38), Capt. Charles Grant, took and burnt French frigate Elize ashore in the Baie de la Hougue

HMS Diana was a 38-gun Artois-class fifth rate frigate of the Royal Navy. She was launched in 1794.

Scale: 1:48. A contemporary full hull model of the 'Diana'-class frigate (1794), a 38-gun fifth-rate, built in 'bread and butter' fashion and finished in the Georgian style. Model is partially decked, equipped, and mounted on its original pillar supports with a modern base. This model clearly illustrates the increasing use of bone and ivory in particular the carved decoration on the stern and the numerous fittings that were turned on a lathe such as the capstan head and deadeyes. This class of frigate were built from plans by Sir John Henslow, Surveyor of the Navy, 1784-1806, and had a gun deck of 146 feet by 39 feet in the beam and a tonnage of 984 (builders old measurement). Known as the 'eyes and ears’ of the fleet, the frigate was used for a variety of roles such as searching out and reporting on the enemy fleets and convoys, as well as independent patrols worldwide.

Type: 38-gun Artois-class fifth rate frigate

Tons burthen: 999 3⁄94 bm

Length:

- 146 ft 3 in (44.6 m) (overall)

- 121 ft 8 1⁄2 in (37.1 m) (keel)

Depth of hold: 13 ft 9 in (4.19 m)

Sail plan: Full-rigged ship

Complement: 270 (later 315)

Armament:

- Upper deck: 28 x 18-pounder guns

- QD: 2 x 9-pounder guns + 12 x 32-pounder carronades

- Fc: 2 x 9-pounder guns + 2 x 32-pounder carronades

Scale: 1:48. A model of one of the nine ships of the 'Artois/Apollo' class of 38-gun frigates designed by Sir John Henslow and built between 1793 and 1795. Seven were built conventionally in private shipyards and two more were constructed experimentally in fir in the Royal Dockyards at Chatham and Woolwich. Four of the conventional ships were wrecked between 1797 and 1799, and the fir-built ships deteriorated rapidly. The model shows the hull of the ship fully planked and set on a launching cradle, though without the rails on which it will run, as is common on models of this period. The stern decoration and figurehead are carefully carved and some features such as decorations and the steering wheel are made in bone. The figurehead is of Diana the huntress, which identifies the ship. Two other models of this ship are in the Museum collection.

Because Diana served in the Royal Navy's Egyptian campaign between 8 March 1801 and 2 September, her officers and crew qualified for the clasp "Egypt" to the Naval General Service Medal that the Admiralty authorized in 1850 to all surviving claimants.

Diana participated in an attack on a French frigate squadron anchored at Saint-Vaast-la-Hougue at the Action of 15 November 1810, which ultimately led to the destruction of the Elisa. (Boats from Diana went in and set fire to the beached Eliza despite heavy fire from shore batteries and three nearby armed brigs; the British suffered no casualties.)

On 7 March 1815 Diana was sold to the Dutch navy for £36,796. On 27 August 1816 she was one of six Dutch frigates that participated in the bombardment of Algiers.

Fate

Diana was accidentally destroyed in a fire on 16 January 1839 while in dry-dock at Willemsoord, Den Helder.

HMS Ethalion in action with the Spanish frigate Thetis off Cape Finisterre, 16 October 1799

The Artois class were a series of nine frigates built to a 1793 design by Sir John Henslow, which served in the Royal Navy during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars.

Seven of these ships were built by contract with commercial builders, while the remaining pair (Tamar and Clyde) were dockyard-built - the latter built using "fir" (pitch pine) instead of the normal oak.

They were armed with a main battery of 28 eighteen-pounder cannon on their upper deck, the main gun deck of a frigate. Besides this battery, they also carried two 9-pounders together with twelve 32-pounder carronades on the quarter deck, and another two 9-pounders together with two 32-pounder carronades on the forecastle.

Scale: approximately 1:32. According to the writing on the side of the hull, this model was made from part of the mainmast of the French flagship ‘L’Orient’ which blew up at the Battle of the Nile in 1798. The model is rather crudely made and its hull is not quite in the right proportions, being too deep, so it is probably sailor-made. The rigging appears to be contemporary. Marmaduke Stalkaart, who also wrote a textbook on naval architecture, built the ‘Seahorse’ (1794) at Rotherhithe on the Thames. It was one of the ‘Artois/Apollo’ class, of which several models exist. The ‘Seahorse’ was not actually present at the Battle of the Nile, but joined Nelson’s fleet soon afterwards.

Ships in class

- HMS Artois

- Builder: John & William Wells, Rotherhithe

- Ordered: 28 March 1793

- Laid down: March 1793

- Launched: 3 January 1794

- Completed: 3 March 1794 at Deptford Dockyard

- Fate: Wrecked on the Ballieu rocks off Brittany on 31 July 1797

- HMS Diana

- Builder: Randall & Co, Rotherhithe

- Ordered: 28 March 1793

- Laid down: March 1793

- Launched: 3 March 1794

- Completed: 6 June 1794 at Deptford Dockyard

- Fate: Sold to new Dutch Navy on 7 March 1815;

burnt in fire at Willemsoord, Den Helder on 16 January 1839.

- HMS Apollo

- Builder: Perry & Hankey, Blackwall

- Ordered: 28 March 1793

- Laid down: March 1793

- Launched: 18 March 1794

- Completed: 23 September 1794 at Woolwich Dockyard

- Fate: Wrecked on the Haak sands off the Dutch coast on 7 January 1799

- HMS Diamond

- Builder: William Barnard, Deptford

- Ordered: 28 March 1793

- Laid down: April 1793

- Launched: 17 March 1794

- Completed: 6 June 1794 at Deptford Dockyard

- Fate: Broken up at Sheerness Dockyard in June 1812

- HMS Jason

- Builder: John Dudman, Deptford

- Ordered: 1 April 1793

- Laid down: April 1793

- Launched: 3 April 1794

- Completed: 25 July 1794 at Deptford Dockyard

- Fate: Wrecked on rocks off Brittany on 13 October 1798

- HMS Seahorse

- Builder: Marmaduke Stalkart, Rotherhithe

- Ordered: 14 February 1793

- Laid down: March 1793

- Launched: 11 June 1794

- Completed: 16 September 1794 at Deptford Dockyard

- Fate: Broken up at Plymouth Dockyard in July 1819

- HMS Tamar

- Builder: Chatham Royal Dockyard

- Ordered: 4 February 1795

- Laid down: June 1795

- Launched: 26 March 1796

- Completed: 21 June 1796

- Fate: Broken up in January 1810 at Chatham Dockyard.

- HMS Clyde

- Builder: Chatham Royal Dockyard

- Ordered: 4 February 1795

- Laid down: June 1795

- Launched: 26 March 1796

- Completed: 21 June 1796

- Fate: Sold to be broken up August 1814.

- HMS Ethalion

- Builder: Joseph Graham, Harwich

- Ordered: 30 April 1795

- Laid down: October 1795

- Launched: 14 March 1797

- Completed: 11 July 1797 at Chatham Dockyard

- Fate: Wrecked on the Penmarcks on 25 December 1799

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Diana_(1794)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artois-class_frigate