Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

18 January 1788 – The first elements of the First Fleet carrying 736 convicts from Great Britain to Australia arrive at Botany Bay - Part II

Voyage

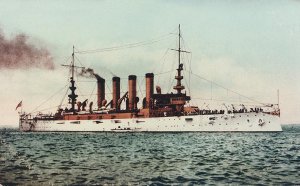

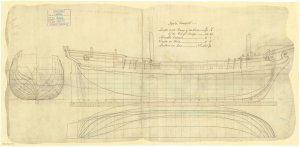

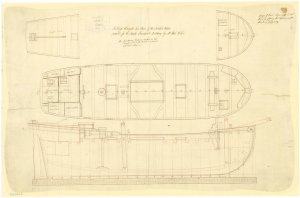

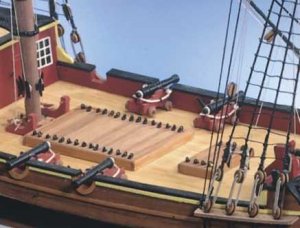

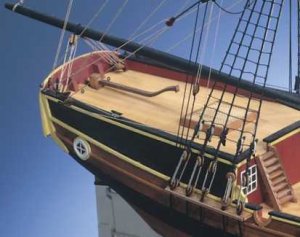

Lady Penrhyn

The First Fleet left Portsmouth, England on 13 May 1787. The journey began with fine weather, and thus the convicts were allowed on deck. The Fleet was accompanied by the armed frigate Hyena until it left English waters. On 20 May 1787, one convict on the Scarborough reported a planned mutiny; those allegedly involved were flogged and two were transferred to Prince of Wales. In general, however, most accounts of the voyage agree that the convicts were well behaved. On 3 June 1787, the fleet anchored at Santa Cruz at Tenerife. Here, fresh water, vegetables and meat were brought on board. Phillip and the chief officers were entertained by the local governor, while one convict tried unsuccessfully to escape. On 10 June they set sail to cross the Atlantic to Rio de Janeiro, taking advantage of favourable trade winds and ocean currents.

The weather became increasingly hot and humid as the Fleet sailed through the tropics. Vermin, such as rats, and parasites such as bedbugs, lice, cockroaches and fleas, tormented the convicts, officers and marines. Bilges became foul and the smell, especially below the closed hatches, was over-powering. While Phillip gave orders that the bilge-water was to be pumped out daily and the bilges cleaned, these orders were not followed on the Alexander and a number of convicts fell sick and died. Tropical rainstorms meant that the convicts could not exercise on deck as they had no change of clothes and no method of drying wet clothing. Consequently, they were kept below in the foul, cramped holds. On the female transports, promiscuity between the convicts, the crew and marines was rampant, despite punishments for some of the men involved. In the doldrums, Phillip was forced to ration the water to three pints a day.

The Fleet reached Rio de Janeiro on 5 August and stayed for a month. The ships were cleaned and water taken on board, repairs were made, and Phillip ordered large quantities of food. The women convicts' clothing had become infested with lice and was burnt. As additional clothing for the female convicts had not arrived before the Fleet left England, the women were issued with new clothes made from rice sacks. While the convicts remained below deck, the officers explored the city and were entertained by its inhabitants. A convict and a marine were punished for passing forged quarter-dollars made from old buckles and pewter spoons.

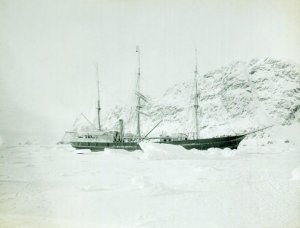

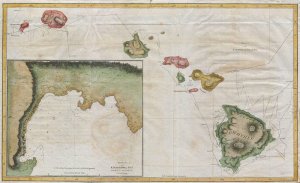

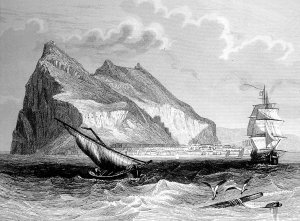

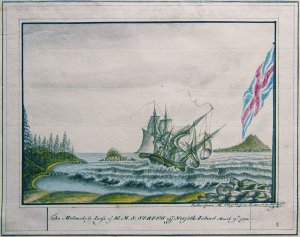

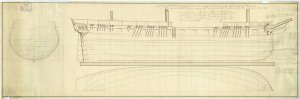

An English Fleet in Table Bay in 1787

The Fleet left Rio de Janeiro on 4 September to run before the westerlies to the Table Bay in southern Africa, which it reached on 13 October. This was the last port of call, so the main task was to stock up on plants, seeds and livestock for their arrival in Australia. The livestock taken on board from Cape Town destined for the new colony included two bulls, seven cows, one stallion, three mares, 44 sheep, 32 pigs, four goats and "a very large quantity of poultry of every kind". Women convicts on the Friendship were moved to other transports to make room for livestock purchased there. The convicts were provided with fresh beef and mutton, bread and vegetables, to build up their strength for the journey and maintain their health. The Dutch colony of Cape Town was the last outpost of European settlement which the fleet members would see for years, perhaps for the rest of their lives. "Before them stretched the awesome, lonely void of the Indian and Southern Oceans, and beyond that lay nothing they could imagine."

Assisted by the gales in the "Roaring Forties" latitudes below the 40th parallel, the heavily laden transports surged through the violent seas. In the last two months of the voyage, the Fleet faced challenging conditions, spending some days becalmed and on others covering significant distances; the Friendship travelled 166 miles one day, while a seaman was blown from the Prince of Wales at night and drowned. Water was rationed as supplies ran low, and the supply of other goods including wine ran out altogether on some vessels. Van Diemen's Land was sighted from the Friendship on 4 January 1788. A freak storm struck as they began to head north around the island, damaging the sails and masts of some of the ships.

On 25 November, Phillip had transferred to the Supply. With Alexander, Friendship and Scarborough, the fastest ships in the Fleet, which were carrying most of the male convicts, the Supply hastened ahead to prepare for the arrival of the rest. Phillip intended to select a suitable location, find good water, clear the ground, and perhaps even have some huts and other structures built before the others arrived. This was a planned move, discussed by the Home Office and the Admiralty prior to the Fleet's departure. However, this "flying squadron" reached Botany Bay only hours before the rest of the Fleet, so no preparatory work was possible. Supply reached Botany Bay on 18 January 1788; the three fastest transports in the advance group arrived on 19 January; slower ships, including Sirius, arrived on 20 January.

This was one of the world's greatest sea voyages – eleven vessels carrying about 1,487 people and stores had travelled for 252 days for more than 15,000 miles (24,000 km) without losing a ship. Forty-eight people died on the journey, a death rate of just over three per cent.

Arrival in Australia

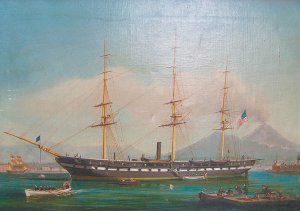

The First Fleet arrives in Port Jackson, 27 January 1788, by William Bradley

It was soon realised that Botany Bay did not live up to the glowing account that the explorer Captain James Cook had provided. The bay was open and unprotected, the water was too shallow to allow the ships to anchor close to the shore, fresh water was scarce, and the soil was poor, First contact was made with the local indigenous people, the Eora, who seemed curious but suspicious of the newcomers. The area was studded with enormously strong trees. When the convicts tried to cut them down, their tools broke and the tree trunks had to be blasted out of the ground with gunpowder. The primitive huts built for the officers and officials quickly collapsed in rainstorms. The marines had a habit of getting drunk and not guarding the convicts properly, whilst their commander, Major Robert Ross, drove Phillip to despair with his arrogant and lazy attitude. Crucially, Phillip worried that his fledgling colony was exposed to attack from Aborigines or foreign powers. Although his initial instructions were to establish the colony at Botany Bay, he was authorised to establish the colony elsewhere if necessary.

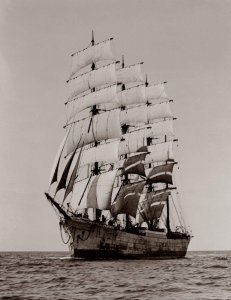

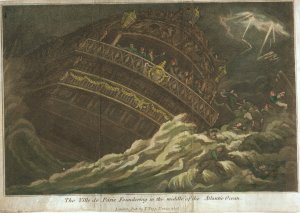

An engraving of the First Fleet in Botany Bay at voyage's end in 1788, from The Voyage of Governor Phillip to Botany Bay. Sirius is in the foreground; convict transports such as Prince of Wales are depicted to the left.

On 21 January, Phillip and a party which included John Hunter, departed the Bay in three small boats to explore other bays to the north. Phillip discovered that Port Jackson, about 12 kilometres to the north, was an excellent site for a colony with sheltered anchorages, fresh water and fertile soil. Cook had seen and named the harbour, but had not entered it. Phillip's impressions of the harbour were recorded in a letter he sent to England later: "the finest harbour in the world, in which a thousand sail of the line may ride in the most perfect security ...". The party returned to Botany Bay on 23 January.

On the morning of 24 January, the party was startled when two French ships were seen just outside Botany Bay. This was a scientific expedition led by Jean-François de La Pérouse. The French had expected to find a thriving colony where they could repair ships and restock supplies, not a newly arrived fleet of convicts considerably more poorly provisioned than themselves. There was some cordial contact between the French and British officers, but Phillip and La Pérouse never met. The French ships remained until 10 March before setting sail on their return voyage. They were not seen again and were later discovered to have been shipwrecked off the coast of Vanikoro in the present-day Solomon Islands.

On 26 January 1788, the Fleet weighed anchor and sailed to Port Jackson. The site selected for the anchorage had deep water close to the shore, was sheltered, and had a small stream flowing into it. Phillip named it Sydney Cove, after Lord Sydney the British Home Secretary. This date is celebrated as Australia Day, marking the beginning of British settlement. The British flag was planted and formal possession taken. This was done by Phillip and some officers and marines from the Supply, with the remainder of Supply's crew and the convicts observing from on board ship. The remaining ships of the Fleet did not arrive at Sydney Cove until later that day.

First contact

The First Fleet encountered indigenous Australians when they landed at Botany Bay. The Cadigal people of the Botany Bay area witnessed the Fleet arrive and six days later the two ships of French explorer La Pérouse sailed into the bay. When the Fleet moved to Sydney Cove seeking better conditions for establishing the colony, they encountered the Eora people, including the Bidjigal clan. A number of the First Fleet journals record encounters with Aboriginal people.

Although the official policy of the British Government was to establish friendly relations with Aboriginal people, and Arthur Phillip ordered that the Aboriginal people should be well treated, it was not long before conflict began. The colonists did not sign treaties with the original inhabitants of the land. Between 1790 and 1810, Pemulwuy of the Bidjigal clan led the local people in a series of attacks against the British colonisers.

After January 1788

The ships of the First Fleet mostly did not remain in the colony. Some returned to England, while others left for other ports. Some remained at the service of the Governor of the colony for some months: some of these were sent to Norfolk Island where a second penal colony was established.

1788

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/First_Fleet

18 January 1788 – The first elements of the First Fleet carrying 736 convicts from Great Britain to Australia arrive at Botany Bay - Part II

Voyage

Lady Penrhyn

The First Fleet left Portsmouth, England on 13 May 1787. The journey began with fine weather, and thus the convicts were allowed on deck. The Fleet was accompanied by the armed frigate Hyena until it left English waters. On 20 May 1787, one convict on the Scarborough reported a planned mutiny; those allegedly involved were flogged and two were transferred to Prince of Wales. In general, however, most accounts of the voyage agree that the convicts were well behaved. On 3 June 1787, the fleet anchored at Santa Cruz at Tenerife. Here, fresh water, vegetables and meat were brought on board. Phillip and the chief officers were entertained by the local governor, while one convict tried unsuccessfully to escape. On 10 June they set sail to cross the Atlantic to Rio de Janeiro, taking advantage of favourable trade winds and ocean currents.

The weather became increasingly hot and humid as the Fleet sailed through the tropics. Vermin, such as rats, and parasites such as bedbugs, lice, cockroaches and fleas, tormented the convicts, officers and marines. Bilges became foul and the smell, especially below the closed hatches, was over-powering. While Phillip gave orders that the bilge-water was to be pumped out daily and the bilges cleaned, these orders were not followed on the Alexander and a number of convicts fell sick and died. Tropical rainstorms meant that the convicts could not exercise on deck as they had no change of clothes and no method of drying wet clothing. Consequently, they were kept below in the foul, cramped holds. On the female transports, promiscuity between the convicts, the crew and marines was rampant, despite punishments for some of the men involved. In the doldrums, Phillip was forced to ration the water to three pints a day.

The Fleet reached Rio de Janeiro on 5 August and stayed for a month. The ships were cleaned and water taken on board, repairs were made, and Phillip ordered large quantities of food. The women convicts' clothing had become infested with lice and was burnt. As additional clothing for the female convicts had not arrived before the Fleet left England, the women were issued with new clothes made from rice sacks. While the convicts remained below deck, the officers explored the city and were entertained by its inhabitants. A convict and a marine were punished for passing forged quarter-dollars made from old buckles and pewter spoons.

An English Fleet in Table Bay in 1787

The Fleet left Rio de Janeiro on 4 September to run before the westerlies to the Table Bay in southern Africa, which it reached on 13 October. This was the last port of call, so the main task was to stock up on plants, seeds and livestock for their arrival in Australia. The livestock taken on board from Cape Town destined for the new colony included two bulls, seven cows, one stallion, three mares, 44 sheep, 32 pigs, four goats and "a very large quantity of poultry of every kind". Women convicts on the Friendship were moved to other transports to make room for livestock purchased there. The convicts were provided with fresh beef and mutton, bread and vegetables, to build up their strength for the journey and maintain their health. The Dutch colony of Cape Town was the last outpost of European settlement which the fleet members would see for years, perhaps for the rest of their lives. "Before them stretched the awesome, lonely void of the Indian and Southern Oceans, and beyond that lay nothing they could imagine."

Assisted by the gales in the "Roaring Forties" latitudes below the 40th parallel, the heavily laden transports surged through the violent seas. In the last two months of the voyage, the Fleet faced challenging conditions, spending some days becalmed and on others covering significant distances; the Friendship travelled 166 miles one day, while a seaman was blown from the Prince of Wales at night and drowned. Water was rationed as supplies ran low, and the supply of other goods including wine ran out altogether on some vessels. Van Diemen's Land was sighted from the Friendship on 4 January 1788. A freak storm struck as they began to head north around the island, damaging the sails and masts of some of the ships.

On 25 November, Phillip had transferred to the Supply. With Alexander, Friendship and Scarborough, the fastest ships in the Fleet, which were carrying most of the male convicts, the Supply hastened ahead to prepare for the arrival of the rest. Phillip intended to select a suitable location, find good water, clear the ground, and perhaps even have some huts and other structures built before the others arrived. This was a planned move, discussed by the Home Office and the Admiralty prior to the Fleet's departure. However, this "flying squadron" reached Botany Bay only hours before the rest of the Fleet, so no preparatory work was possible. Supply reached Botany Bay on 18 January 1788; the three fastest transports in the advance group arrived on 19 January; slower ships, including Sirius, arrived on 20 January.

This was one of the world's greatest sea voyages – eleven vessels carrying about 1,487 people and stores had travelled for 252 days for more than 15,000 miles (24,000 km) without losing a ship. Forty-eight people died on the journey, a death rate of just over three per cent.

Arrival in Australia

The First Fleet arrives in Port Jackson, 27 January 1788, by William Bradley

It was soon realised that Botany Bay did not live up to the glowing account that the explorer Captain James Cook had provided. The bay was open and unprotected, the water was too shallow to allow the ships to anchor close to the shore, fresh water was scarce, and the soil was poor, First contact was made with the local indigenous people, the Eora, who seemed curious but suspicious of the newcomers. The area was studded with enormously strong trees. When the convicts tried to cut them down, their tools broke and the tree trunks had to be blasted out of the ground with gunpowder. The primitive huts built for the officers and officials quickly collapsed in rainstorms. The marines had a habit of getting drunk and not guarding the convicts properly, whilst their commander, Major Robert Ross, drove Phillip to despair with his arrogant and lazy attitude. Crucially, Phillip worried that his fledgling colony was exposed to attack from Aborigines or foreign powers. Although his initial instructions were to establish the colony at Botany Bay, he was authorised to establish the colony elsewhere if necessary.

An engraving of the First Fleet in Botany Bay at voyage's end in 1788, from The Voyage of Governor Phillip to Botany Bay. Sirius is in the foreground; convict transports such as Prince of Wales are depicted to the left.

On 21 January, Phillip and a party which included John Hunter, departed the Bay in three small boats to explore other bays to the north. Phillip discovered that Port Jackson, about 12 kilometres to the north, was an excellent site for a colony with sheltered anchorages, fresh water and fertile soil. Cook had seen and named the harbour, but had not entered it. Phillip's impressions of the harbour were recorded in a letter he sent to England later: "the finest harbour in the world, in which a thousand sail of the line may ride in the most perfect security ...". The party returned to Botany Bay on 23 January.

On the morning of 24 January, the party was startled when two French ships were seen just outside Botany Bay. This was a scientific expedition led by Jean-François de La Pérouse. The French had expected to find a thriving colony where they could repair ships and restock supplies, not a newly arrived fleet of convicts considerably more poorly provisioned than themselves. There was some cordial contact between the French and British officers, but Phillip and La Pérouse never met. The French ships remained until 10 March before setting sail on their return voyage. They were not seen again and were later discovered to have been shipwrecked off the coast of Vanikoro in the present-day Solomon Islands.

On 26 January 1788, the Fleet weighed anchor and sailed to Port Jackson. The site selected for the anchorage had deep water close to the shore, was sheltered, and had a small stream flowing into it. Phillip named it Sydney Cove, after Lord Sydney the British Home Secretary. This date is celebrated as Australia Day, marking the beginning of British settlement. The British flag was planted and formal possession taken. This was done by Phillip and some officers and marines from the Supply, with the remainder of Supply's crew and the convicts observing from on board ship. The remaining ships of the Fleet did not arrive at Sydney Cove until later that day.

First contact

The First Fleet encountered indigenous Australians when they landed at Botany Bay. The Cadigal people of the Botany Bay area witnessed the Fleet arrive and six days later the two ships of French explorer La Pérouse sailed into the bay. When the Fleet moved to Sydney Cove seeking better conditions for establishing the colony, they encountered the Eora people, including the Bidjigal clan. A number of the First Fleet journals record encounters with Aboriginal people.

Although the official policy of the British Government was to establish friendly relations with Aboriginal people, and Arthur Phillip ordered that the Aboriginal people should be well treated, it was not long before conflict began. The colonists did not sign treaties with the original inhabitants of the land. Between 1790 and 1810, Pemulwuy of the Bidjigal clan led the local people in a series of attacks against the British colonisers.

After January 1788

The ships of the First Fleet mostly did not remain in the colony. Some returned to England, while others left for other ports. Some remained at the service of the Governor of the colony for some months: some of these were sent to Norfolk Island where a second penal colony was established.

1788

- 15 February – HMS Supply sails for Norfolk Island carrying a small party to establish a settlement.

- 5/6 May – Charlotte, Lady Penrhyn and Scarborough set sail for China.

- 14 July – Borrowdale, Alexander, Friendship and Prince of Wales set sail to return to England.

- 2 October – Golden Grove sets sail for Norfolk Island with a party of convicts, returning to Port Jackson 10 November, while HMS Sirius sails for Cape of Good Hope for supplies.

- 19 November – Fishburn and Golden Grove set sail for England. This means that only HMS Supply now remains in Sydney cove.

- 23 December – HMS Guardian carrying stores for the colony strikes an iceberg and is forced back to the Cape. It never reaches the colony in New South Wales.

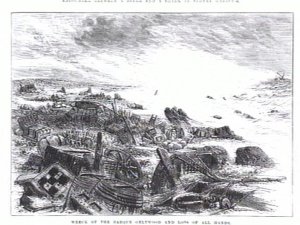

- 19 March – HMS Sirius is wrecked off Norfolk Island.

- 17 April – HMS Supply sent to Batavia, Java, for emergency food supplies.

- 3 June – Lady Juliana, the first of six vessels of the Second Fleet, arrives in Sydney cove. The remaining five vessels of the Second Fleet arrive in the ensuing weeks.

- 19 September – HMS Supply returns to Sydney having chartered the Dutch vessel Waaksamheid to accompany it carrying stores.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/First_Fleet

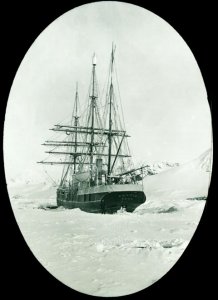

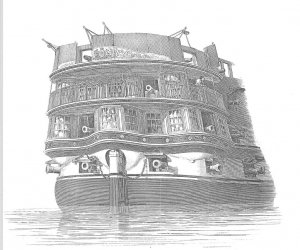

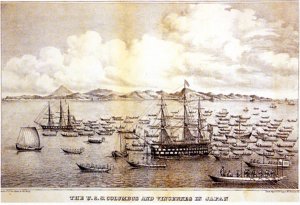

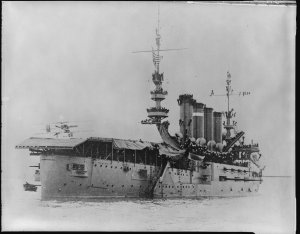

from HMS Sirius in Sydney

from HMS Sirius in Sydney

, Virginia

, Virginia