Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

20 May 1570 - Abraham Ortelius published Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, the "first modern atlas"

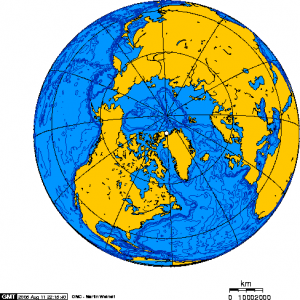

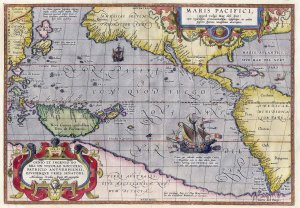

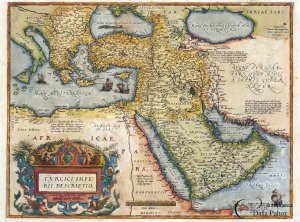

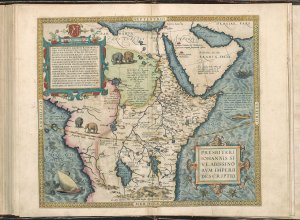

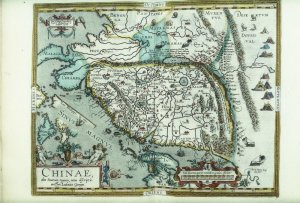

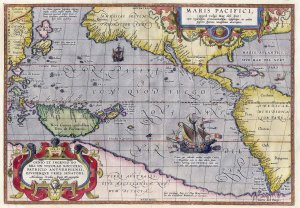

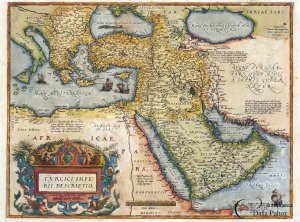

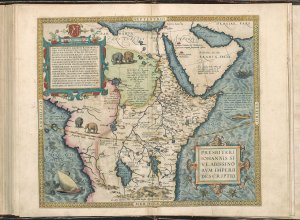

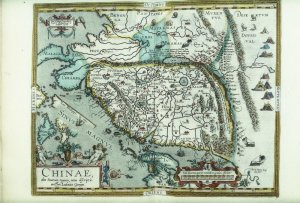

Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (Latin: [tʰɛˈaːtrʊm ˈɔrbɪs tɛˈrːaːrʊm], "Theatre of the World") is considered to be the first true modern atlas. Written by Abraham Ortelius, strongly encouraged by Gillis Hooftman and originally printed on May 20, 1570, in Antwerp, it consisted of a collection of uniform map sheets and sustaining text bound to form a book for which copper printing plates were specifically engraved. The Ortelius atlas is sometimes referred to as the summary of sixteenth-century cartography. The publication of the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (1570) is often considered as the official beginning of the Golden Age of Netherlandish cartography (approximately 1570s–1670s).

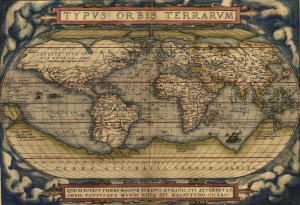

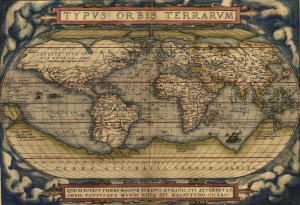

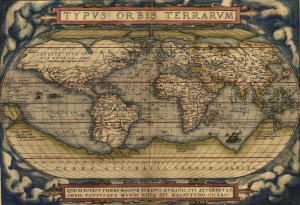

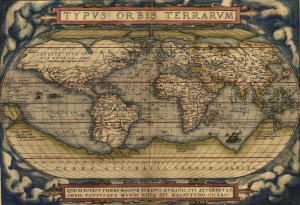

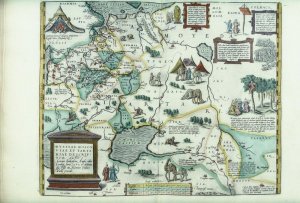

In 1570 (May 20) Gilles Coppens de Diest at Antwerp published 53 maps created by Abraham Ortelius under the title Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, considered the "first modern atlas".[note 1] Three Latin editions of this (besides a Dutch, a French and a German edition) appeared before the end of 1572; twenty-five editions came out before Ortelius' death in 1598; and several others were published subsequently, for the atlas continued to be in demand till about 1612. This is the world map from this atlas.

Content

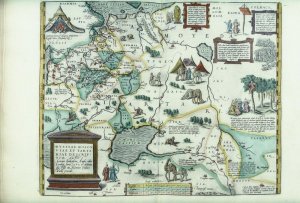

The atlas contained virtually no maps from the hand of Ortelius, but 53 bundled maps of other masters, with the source as indicated. Previously, only the pooling of disparate maps were released as custom on order. The Ortelius atlas, however, dropped the maps for this all in the same style and on the same size on copper plates, logically arranged by continent, region and State. He provided the maps in addition to a descriptive comment and referrals on the reverse. As such, this was the first time that the entirety of Western European knowledge of the world was brought together in one book.

In the bibliography, the section Catalogue Auctorum, not only were the 33 cartographers mentioned, whose work in the Theatrum was recorded (at that time not yet the habit), but also the total of 87 cartographers of the 16th century that Ortelius knew. This list grew in every Latin Edition, and included no less than 183 names in 1601. Among the sources are mentioned among other things the following: for the world map the World Map (1561) by Giacomo Gastaldi, the porto Avenue of the Atlantic coast (1562) by Diego Gutierrez, the world map (1569) of Gerardus Mercator, which have 8 maps derived from the Theatrum.

For the map of Europe, wall map (1554). of the Mercator map of Scandinavia (1539) by Olaus Magnus, map of Asia was derived from his own Asia-map from 1567, which in turn was inspired by that of Gastaldi (1559). Also for the Africa map he referred to Gastaldi.

This work by Ortelius, consisted of a collection of the best maps, refined by himself, combined into one map or split across multiple, and on the same size (folios of approximately 35 x 50 cm). The naming and location coordinates were not normalized.

Editions

After the initial publication of Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, Ortelius regularly revised and expanded the atlas,[3] reissuing it in various formats until his death in 1598. From its original seventy maps and eighty-seven bibliographic references in the first edition (1570), the atlas grew through its thirty-one editions to encompass 183 references and 167 maps in 1612.

The online copy of the 1573 volume held by the State Library of New South Wales contains 70 numbered double-page sheets, tipped onto stubs at the centerfold, with 6 maps combined with descriptive letterpress on the recto of each first leaf. The legends of most maps name the author whose map Ortelius adapted. In the preface Ortelius credits Franciscus Hogenberg with engraving nearly all the maps.

The 1573 Additamentum to the atlas is notable for containing Humphrey Llwyd's Cambriae Typus, the first map to show Wales on its own.

From the 1630s, the Blaeu family issued their work under a similar title, Theatrum orbis terrarum, sive, Atlas Novus.

Structure

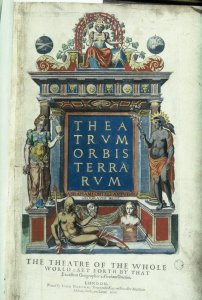

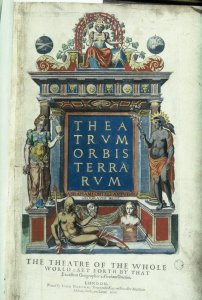

Title page from a 1606 edition with female figures representing the continents

All those editions had the same structure. They started with an allegorical title page, on which the five known continents, were presented by allegorical women, with Europe as the Queen. Then a command to Philip II, King of Spain and the low countries, and a poem by Adolphus Mekerchus (Adolf of Meetkercke). From 1579, the editions contain a portrait of Ortelius by Philip Galle, an introduction by Ortelius, in the Latin editions followed by a recommendation by Mercator. This is followed by the bibliography (Auctorum Catalog), an index (Index Tabularum), the cards with text on the back, starting from 1579 in the Latin editions followed by a register of place names in ancient times (Nomenclator), the treatise, the Mona Druidum insula of the Welsh scientist Humphrey Lhuyd (Humphrey Llwyd) over the Anglesey coat of arms, and finally the privilege and a colophon.

Cost

The moneyed middle class, which had much interest in knowledge and science, turned out to be very much interested in the convenient size and the pooling of knowledge. For buyers who were not strong in Latin, published at the end of 1572, in addition to three Latin, there were a Dutch, German and French 2nd Edition. This rapid success prompted the Ortelius Theatrum constantly continued to expand and improve. In 1573, he released 17 more additional maps under the title Additamentum Theatri Orbis Terrarum, which in these master works were published, bringing the total at 70 maps. By Ortelius' death in 1598, there were twenty-five editions that appeared in seven different languages.

en.wikipedia.org

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theatrum_Orbis_Terrarum

en.wikipedia.org

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theatrum_Orbis_Terrarum

20 May 1570 - Abraham Ortelius published Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, the "first modern atlas"

Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (Latin: [tʰɛˈaːtrʊm ˈɔrbɪs tɛˈrːaːrʊm], "Theatre of the World") is considered to be the first true modern atlas. Written by Abraham Ortelius, strongly encouraged by Gillis Hooftman and originally printed on May 20, 1570, in Antwerp, it consisted of a collection of uniform map sheets and sustaining text bound to form a book for which copper printing plates were specifically engraved. The Ortelius atlas is sometimes referred to as the summary of sixteenth-century cartography. The publication of the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (1570) is often considered as the official beginning of the Golden Age of Netherlandish cartography (approximately 1570s–1670s).

In 1570 (May 20) Gilles Coppens de Diest at Antwerp published 53 maps created by Abraham Ortelius under the title Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, considered the "first modern atlas".[note 1] Three Latin editions of this (besides a Dutch, a French and a German edition) appeared before the end of 1572; twenty-five editions came out before Ortelius' death in 1598; and several others were published subsequently, for the atlas continued to be in demand till about 1612. This is the world map from this atlas.

Content

The atlas contained virtually no maps from the hand of Ortelius, but 53 bundled maps of other masters, with the source as indicated. Previously, only the pooling of disparate maps were released as custom on order. The Ortelius atlas, however, dropped the maps for this all in the same style and on the same size on copper plates, logically arranged by continent, region and State. He provided the maps in addition to a descriptive comment and referrals on the reverse. As such, this was the first time that the entirety of Western European knowledge of the world was brought together in one book.

In the bibliography, the section Catalogue Auctorum, not only were the 33 cartographers mentioned, whose work in the Theatrum was recorded (at that time not yet the habit), but also the total of 87 cartographers of the 16th century that Ortelius knew. This list grew in every Latin Edition, and included no less than 183 names in 1601. Among the sources are mentioned among other things the following: for the world map the World Map (1561) by Giacomo Gastaldi, the porto Avenue of the Atlantic coast (1562) by Diego Gutierrez, the world map (1569) of Gerardus Mercator, which have 8 maps derived from the Theatrum.

For the map of Europe, wall map (1554). of the Mercator map of Scandinavia (1539) by Olaus Magnus, map of Asia was derived from his own Asia-map from 1567, which in turn was inspired by that of Gastaldi (1559). Also for the Africa map he referred to Gastaldi.

This work by Ortelius, consisted of a collection of the best maps, refined by himself, combined into one map or split across multiple, and on the same size (folios of approximately 35 x 50 cm). The naming and location coordinates were not normalized.

Editions

After the initial publication of Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, Ortelius regularly revised and expanded the atlas,[3] reissuing it in various formats until his death in 1598. From its original seventy maps and eighty-seven bibliographic references in the first edition (1570), the atlas grew through its thirty-one editions to encompass 183 references and 167 maps in 1612.

The online copy of the 1573 volume held by the State Library of New South Wales contains 70 numbered double-page sheets, tipped onto stubs at the centerfold, with 6 maps combined with descriptive letterpress on the recto of each first leaf. The legends of most maps name the author whose map Ortelius adapted. In the preface Ortelius credits Franciscus Hogenberg with engraving nearly all the maps.

The 1573 Additamentum to the atlas is notable for containing Humphrey Llwyd's Cambriae Typus, the first map to show Wales on its own.

From the 1630s, the Blaeu family issued their work under a similar title, Theatrum orbis terrarum, sive, Atlas Novus.

Structure

Title page from a 1606 edition with female figures representing the continents

All those editions had the same structure. They started with an allegorical title page, on which the five known continents, were presented by allegorical women, with Europe as the Queen. Then a command to Philip II, King of Spain and the low countries, and a poem by Adolphus Mekerchus (Adolf of Meetkercke). From 1579, the editions contain a portrait of Ortelius by Philip Galle, an introduction by Ortelius, in the Latin editions followed by a recommendation by Mercator. This is followed by the bibliography (Auctorum Catalog), an index (Index Tabularum), the cards with text on the back, starting from 1579 in the Latin editions followed by a register of place names in ancient times (Nomenclator), the treatise, the Mona Druidum insula of the Welsh scientist Humphrey Lhuyd (Humphrey Llwyd) over the Anglesey coat of arms, and finally the privilege and a colophon.

Cost

The moneyed middle class, which had much interest in knowledge and science, turned out to be very much interested in the convenient size and the pooling of knowledge. For buyers who were not strong in Latin, published at the end of 1572, in addition to three Latin, there were a Dutch, German and French 2nd Edition. This rapid success prompted the Ortelius Theatrum constantly continued to expand and improve. In 1573, he released 17 more additional maps under the title Additamentum Theatri Orbis Terrarum, which in these master works were published, bringing the total at 70 maps. By Ortelius' death in 1598, there were twenty-five editions that appeared in seven different languages.

Abraham Ortelius - Wikipedia

Abraham Ortelius - Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (1570) - Ficta eloquentia

****************************************************************************** ****************************************************************************** ******************************************************************************...

jorgeledo.net