I am taking a slightly different tack.

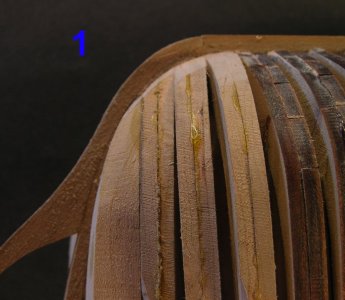

I build POF - stylized - no planking below the main wale.

I also hate cant frames. I will not use them. There is not all that much frame timber below the wale in the zone where cant frames live anyway. I use full frames just as far as the Body plan has stations.

Many of the stylized 17thC, Navy Board models did the same thing.

The pre-1776 Georgians were either crude block models or POF with full frames from hawse to transoms.

I tried to be thorough in my sweeps of the RMG website and I find only three exceptions in my era of interest (1719-1776) Intrepid 64 1770, Bellona 74 1760, Victory 100 1765.

These three are framing only and they do have cant frames. - If they were not Well they should have been engineering classroom demonstration models for the young gentlemen. The last two vessels are so over done as subjects for models that I have no interest what so ever in building a model of either of them.

There is one serious chore that comes from doing full frames all the way - the bevel is extreme. Way more wood is taken off than remains. It is worse at the bow.

This extreme bevel is why cant frames were used. Even if timber stock with the large dimensions necessary could be had, the racked rectangle cross section of what was left may not have had the required strength. For a model, having the necessary framing stock size is no problem.

The problem that faced cant design is a wide outside arc that is essentially 90 degrees and a limited space for the heels on the deadwood. The heel of a cant frame were almost always in contact with the heel of the frame on either side. This tends to limit how much outside arc can have frame support.

If T was forced to model cant frames here is how I would do it:

I use a raster drawing program.

Each cant frame is a unique unit.

WL plan XZ

If your WL plan is not only the actual lines. If the background is not transparent. Use the magic wand selector and do whatever it takes to CUT everything but the actual lines.

If the lines are too faint - use the bucket fill and darken the lines with 000-000-000 and or background/contrast at -100 -100 - whatever it takes and how many clicks of the bucket are needed to get the lines dark enough.

Choose a cant frame

Place a baseline at the heel of the forward face where it intersects with the baseline (center of keel) of the WL plan. This line is to be perpendicular to the plane of the face.

Use rectangular SELECT to COPY the frame face line and include all of the WL and the rail - everything on the WL plan- PASTE to new layer. = Layer 1

If the cant is a bend, do the same for the midline. Layer 2

Do the same for the deadflat face Layer 3

Duplicate Layer 1.

Always use duplicates!

Experiment with Rotate degree values until you find the value that has the face line be perpendicular to the WL centerline. and your drawn frame baseline exactly overlays the WL centerline. If both do not happen go back and place a new frame baseline that does. Write the value down on your data card. This is also the value for layer 2 and layer 3

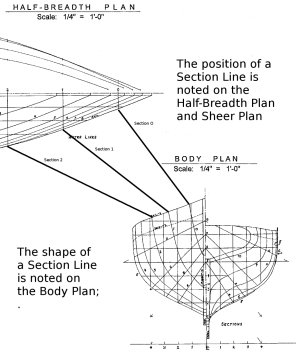

The BODY plan XY has a vertical centerline - a horizontal baseline - a horizontal line for every WL - the rail is ambiguous/unclear - a vertical line for every Buttock line. The station line patterns are not needed - get in the way - confuse and obstruct. Only the grid is wanted.

Rotate Layer 1 90 degrees ( a copy of layer 1) The face of the frame should be horizontal and the base should overlay the vertical centerline.

Make as many copies of Layer 1 as there are data points on the WL plan.

On copy 1 CUT everything but rabbet at keel data point - place the layer at that horizontal level

On copy 2 CUT everything but WL 1 data point set it at WL1 level

Repeat for every WL

Go to the Profile/Sheer plan. YZ

There are no frame lines except the stations.

What is needed is the vertical distance from the baseline to the cant frame face line for each Buttock line and any other lines like wales and rail. The cant is oblique on this plan.

OK - what is needed is the combined WL and Profile plan.

The WL plan defines where a cant frame line crosses each wale and rail.

Place a loooong vertical line at the intersection of the rail and the cant line.

Go up to the Profile plan COPY the vertical line from profile baseline to the rail SAVE to its own layer

COPY the lower part of this vertical line from the WL baseline to the rail point - This how far out it is. Save to its own layer.

Rotate it 90 degrees. Open both layers. Move the how horizontal how far out it is line until it is at the baseline of the how far up it is line.

COLLAPSE to a single layer. This new layer now has how far up and how far out for the rail.

Do this for every wale and rail.

Go back to the BODY plan

Place the rail data point at it proper X distance. CUT the parts that get in the way.

Repeat for every Profile data point that is each Buttock line and every wale and rail.

When done there should be a series of points that define the outside shape for the forward face of the cant frame.

Now comes the fun part! Connect the points with the proper curve that belongs in the series.

My drawing program has a freehand continuous curve following the cursor function - I cannot use this - too shaky and unsure.

A connect the dots function. Click at a spot - move the cursor click a new spot and a straight line connects the two. I use this. It is facets - not a smooth curve. If the dots are close it looks like a curve. Sand or carve or plane the wood using it and it is a curve. It is impossible to make it facets.

For full frames, the curves of the previous frame - or in my case station - provide a good guide to get the needed transition.

OK doing this is tedious, repetitive, time consuming, and boring. Would not sticking with only do as full frames be the more sane option?