.

This is a pioneering undertaking of sorts, as it concerns what is probably the oldest technical plan of a French ship (actually a battleship design submitted to the authorities) by the highly productive shipwright Laurent Hubac, who, of all the other shipwrights, built probably the most ships for Louis XIV's so-called first fleet, and to my knowledge, no one has yet made a (correct) conceptual reconstruction of this 1679 design.

The relevant explanations by Jean Boudriot, in my opinion the best expert in this particular field, i.e. historical naval architecture, do not cover this early period, as they only begin with the first decades of the 18th century, being based on written sources that appeared only at that somewhat later time (omitting the ‘age-old’ Mediterranean method, irrelevant in this context, and called by the French the méthode de maître-gabarit, la tablette et le trébuchet). The results of similar attempts at reconstructing ships from this period by Jean-Claude Lemineur, author of otherwise excellent monographs on ships from this period, are not convincing, nor are the explanations in a recent archaeological monograph by Texas A&M University Press on the French ship La Belle 1684, i.e. from the very same period.

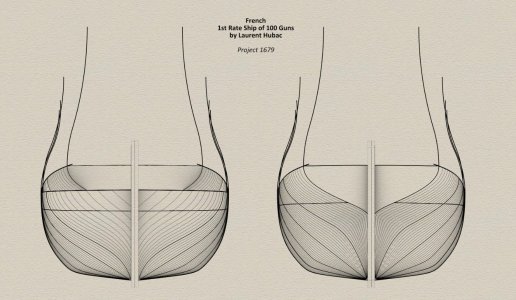

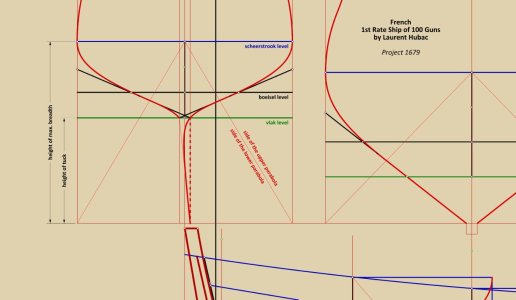

The conceptual method found in this project seems to be the same as the one I have already described in threads on this forum concerning Dutch ship designs from about the same period, more specifically, a variant involving the formation of frames using conical curves.

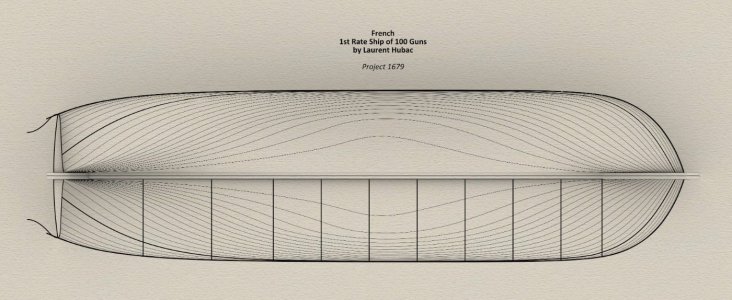

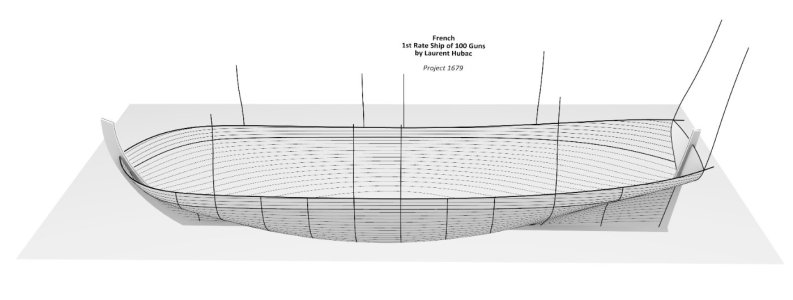

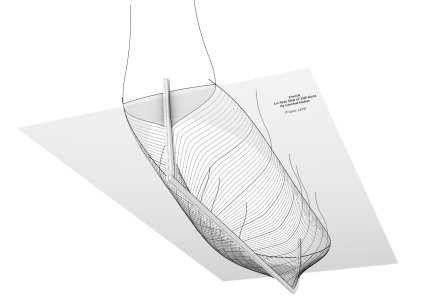

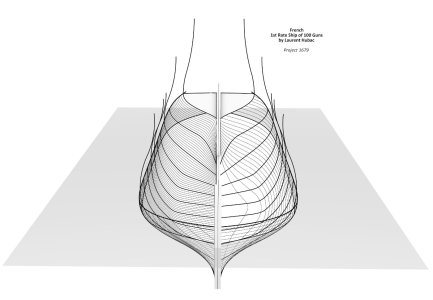

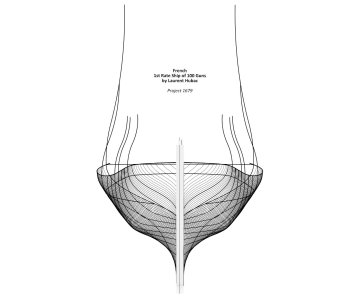

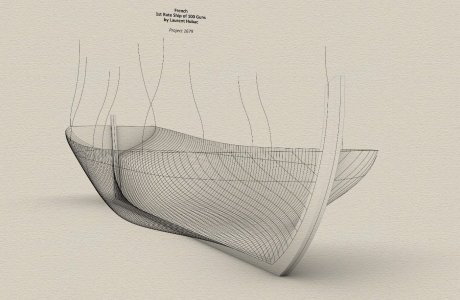

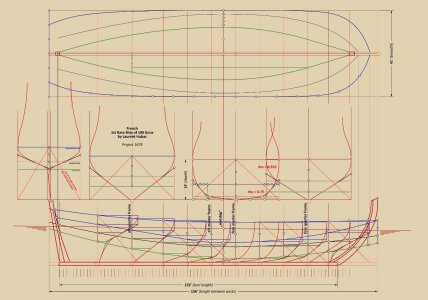

The results of the conceptual reconstruction are the hull lines of Hubac's ship project, presented in the renderings below. The very sharp lines of the hull are striking, especially for such a ‘heavy’ capital ship, as is the fairly pronounced sharp bulge in the central part of the hull at the junction of the bottom and the side, quite resembling a feature characteristic of Dutch shipbuilding (Hubac himself was of Dutch origin).

Waldemar Gurgul

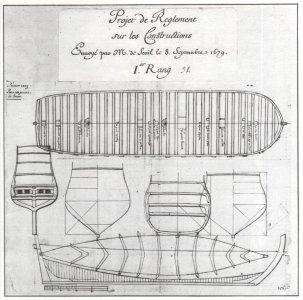

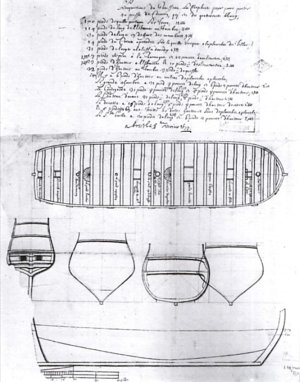

Original plan from 1679 by Laurent Hubac (French archives):

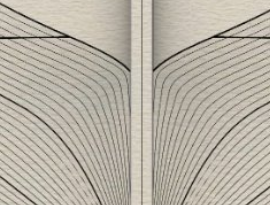

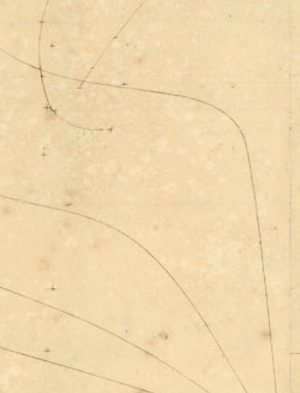

Reconstruction graphics:

.