- Joined

- Dec 7, 2022

- Messages

- 114

- Points

- 78

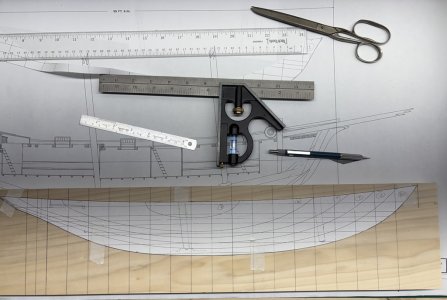

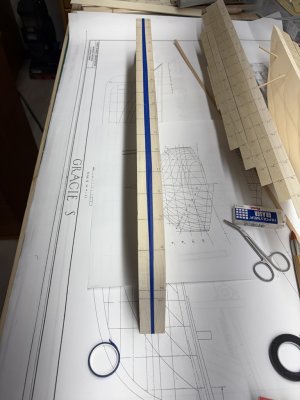

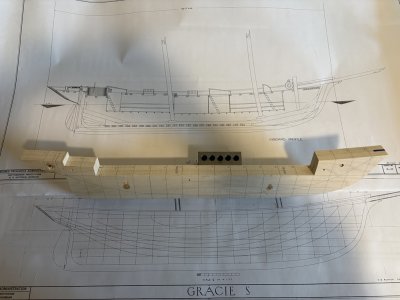

Within this thread I plan on demonstrating how the hull of Gracie S. can be fabricated using a lift technique.

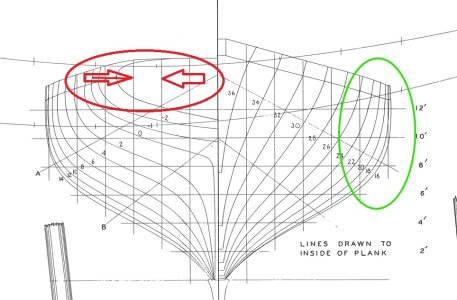

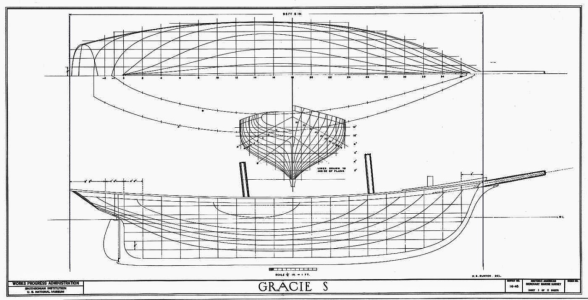

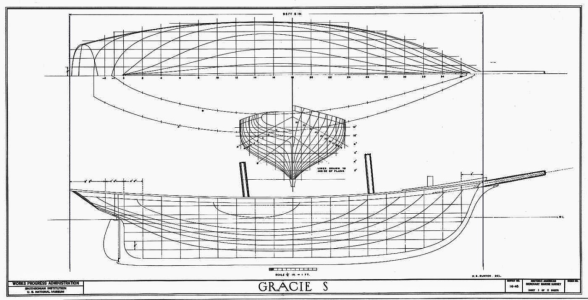

A few days ago Dave Stevens, in the PLANS thread, posted this image of the plans for Gracie S from the Historic American Merchant Marine Survey (HAMMS):

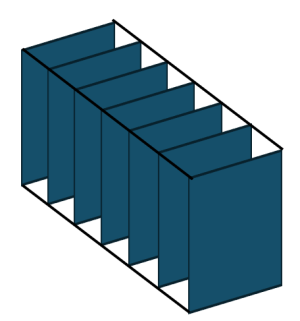

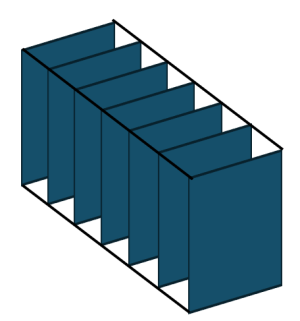

If you think of Gracie's hull sitting in a rectangular solid, then the vertical and horizontal lines in the three views above can be aligned with three sets of slices in the rectangular solid. One set of slices cuts the rectangular solid like a loaf of bread - there are 20 such cuts in Gracie's plans. The intersection of Gracie's hull with these cuts gives rise to the body plan seen in the middle of the HAMMS plan above.

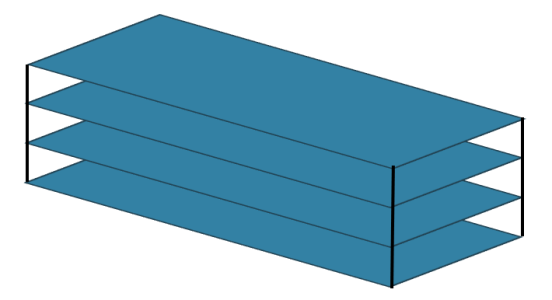

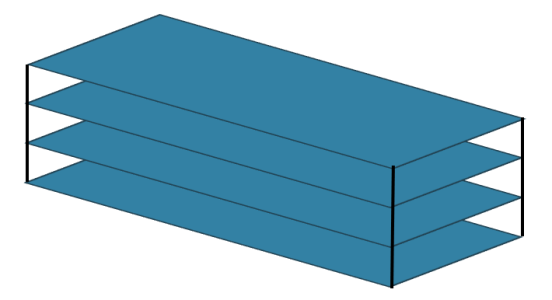

A second set of slices is like layers in a cake - there are 7 layers in Gracie's plans. The intersections of Gracie's hull with these cuts give rise to waterlines - the shape of these curves can be viewed on the top drawing in the plan above.

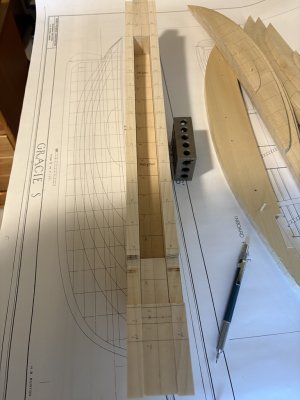

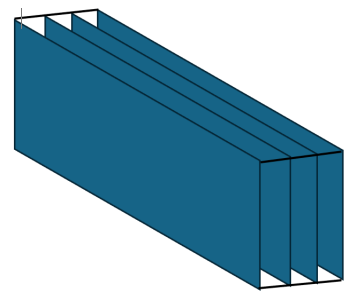

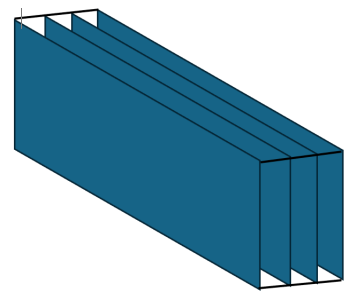

A third set of slices can be made as vertical slices from front to back - there are 14 layers in Gracie's plans. The intersection of Gracie's hull with these slices are called buttock lines and can be viewed on the lower drawing of the HAMMS plan.

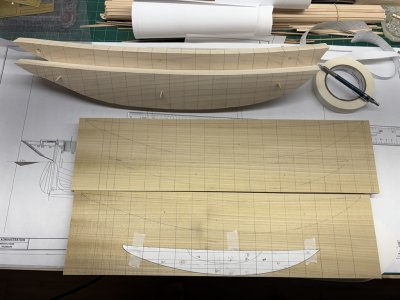

Plank on bulkhead (POB) and plank on frame models (POF) rely heavily on the body plan for shaping bulkheads (molds) and/or frames. If one fills in the region between bulkheads / frames a solid hull can be had - this is actually a type of lift model. However, it is more traditional to view lift models as coming about by making use of waterlines or by buttock lines.

In Grimwood's book American Ship Models and How to Build Them the focus is on building lift models based on horizontal waterline lifts. As an example, the second vessel in the book is the Piscataqua gondalow 'Fannie M.' that can be fabricated out of 5 lifts based on the provided plans.

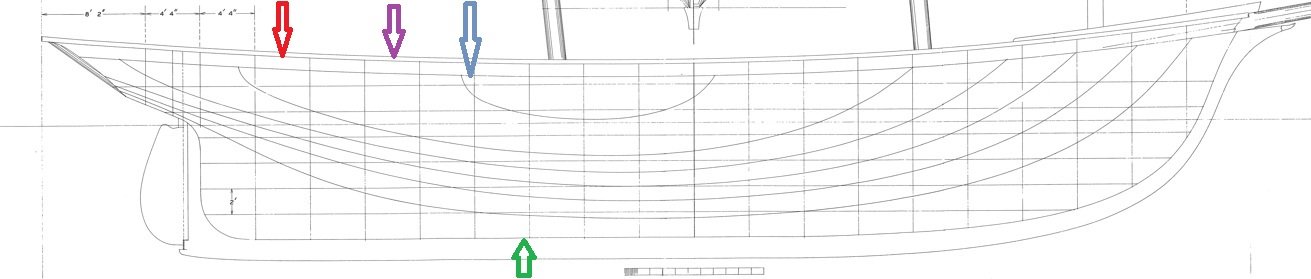

The lifts are glued together and shaped using edges of the lifts as guidelines:

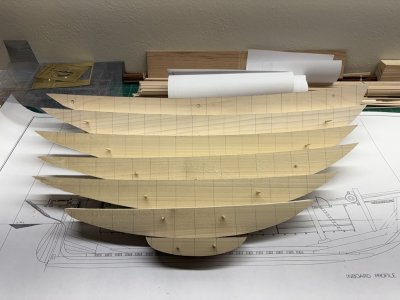

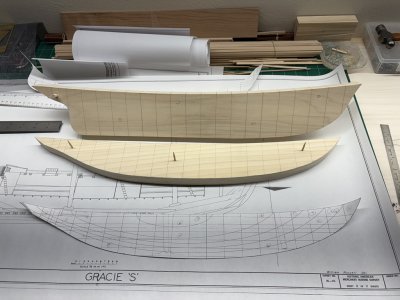

After some time the smooth hull shape appears!

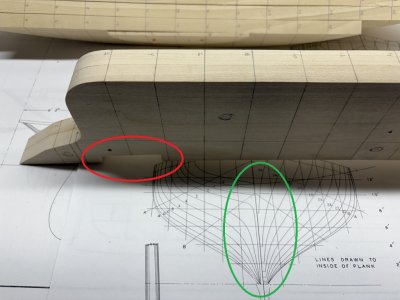

Notice that the exterior of this hull is completely convex in nature. This made shaping the hull a relatively straightforward task. Gracie's hull is much more complicated having both concave and convex surfaces.

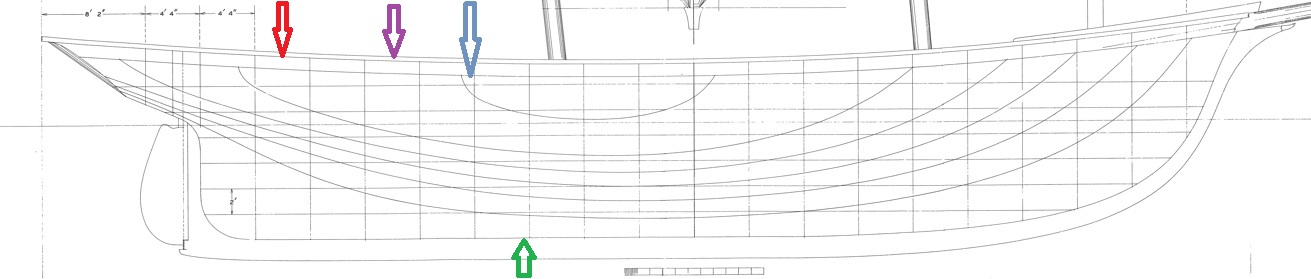

In the next post I will explain why I have chosen to use vertical / bottock lifts for my model of Gracie S.

A few days ago Dave Stevens, in the PLANS thread, posted this image of the plans for Gracie S from the Historic American Merchant Marine Survey (HAMMS):

If you think of Gracie's hull sitting in a rectangular solid, then the vertical and horizontal lines in the three views above can be aligned with three sets of slices in the rectangular solid. One set of slices cuts the rectangular solid like a loaf of bread - there are 20 such cuts in Gracie's plans. The intersection of Gracie's hull with these cuts gives rise to the body plan seen in the middle of the HAMMS plan above.

A second set of slices is like layers in a cake - there are 7 layers in Gracie's plans. The intersections of Gracie's hull with these cuts give rise to waterlines - the shape of these curves can be viewed on the top drawing in the plan above.

A third set of slices can be made as vertical slices from front to back - there are 14 layers in Gracie's plans. The intersection of Gracie's hull with these slices are called buttock lines and can be viewed on the lower drawing of the HAMMS plan.

Plank on bulkhead (POB) and plank on frame models (POF) rely heavily on the body plan for shaping bulkheads (molds) and/or frames. If one fills in the region between bulkheads / frames a solid hull can be had - this is actually a type of lift model. However, it is more traditional to view lift models as coming about by making use of waterlines or by buttock lines.

In Grimwood's book American Ship Models and How to Build Them the focus is on building lift models based on horizontal waterline lifts. As an example, the second vessel in the book is the Piscataqua gondalow 'Fannie M.' that can be fabricated out of 5 lifts based on the provided plans.

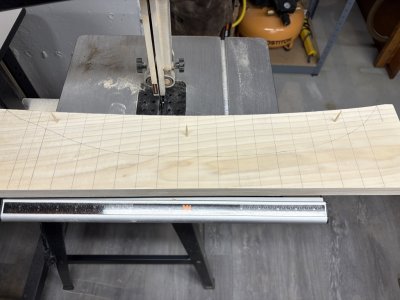

The lifts are glued together and shaped using edges of the lifts as guidelines:

After some time the smooth hull shape appears!

Notice that the exterior of this hull is completely convex in nature. This made shaping the hull a relatively straightforward task. Gracie's hull is much more complicated having both concave and convex surfaces.

In the next post I will explain why I have chosen to use vertical / bottock lifts for my model of Gracie S.