.

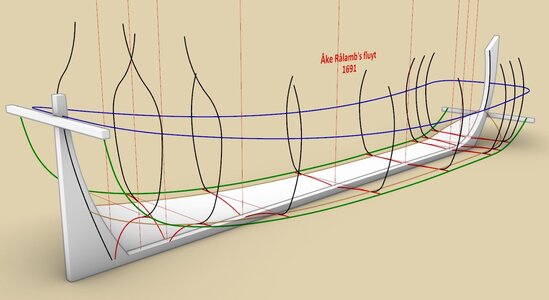

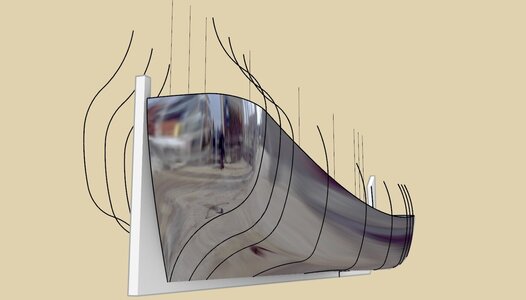

The first attempts with the 3D reconstruction model are coming out very well, so I think the thread can now be started. Why should they not come out? The method is so easy and even fool-proof that small children could manage it.

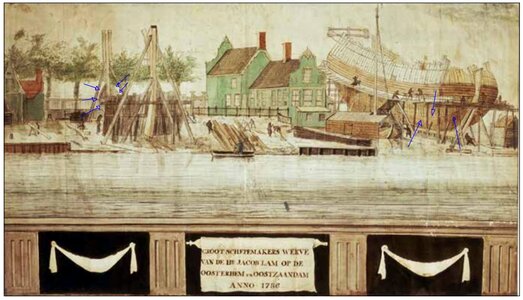

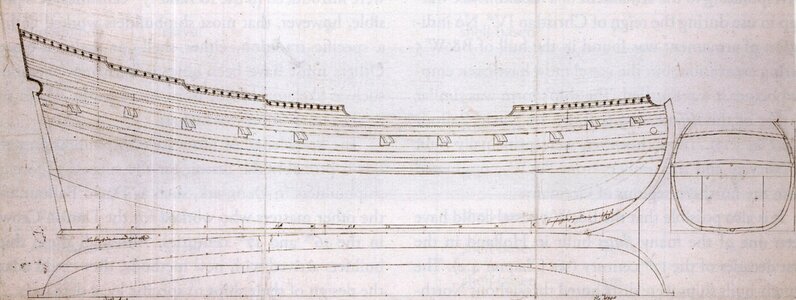

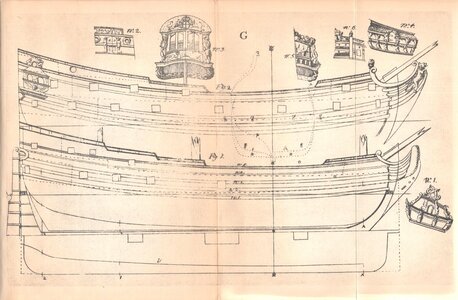

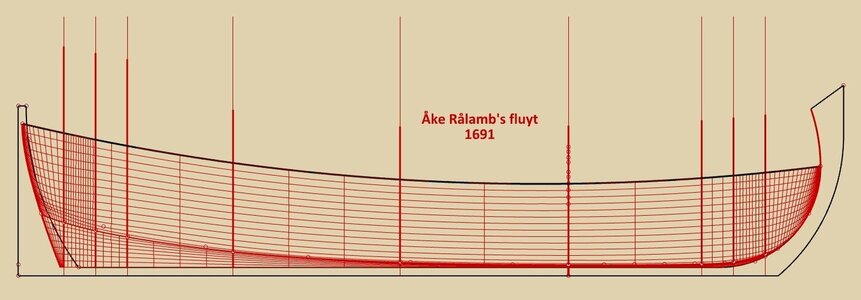

But to the point. The fluyt from plate G in the work Skeps Byggerij 1691 by Åke Rålamb, is a highly specialised type of merchant ship widely used in a number of variants. This one is 130 feet long and 28 feet wide (L/B = 4.64:1) and has characteristics typical of vessels sailing in the northern waters of the continent (Fig. 1).

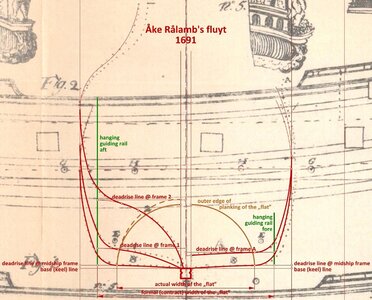

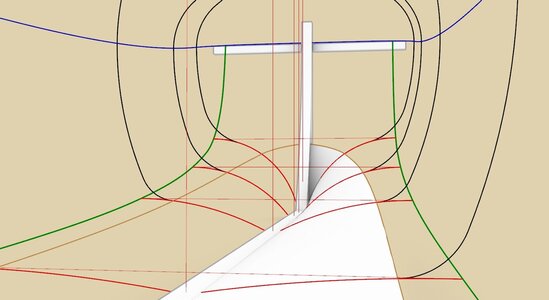

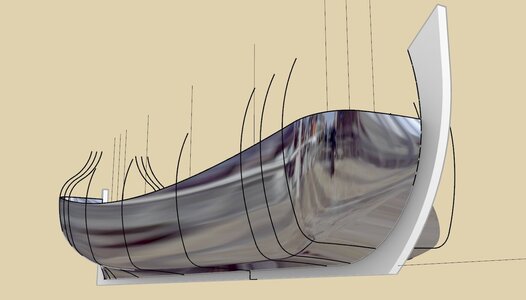

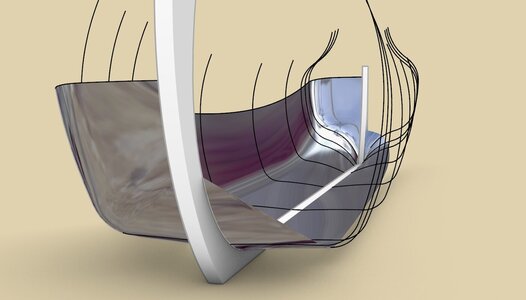

In design terms, the drawing itself can be interpreted in several ways. For the main presentation, I have chosen a non-graphical variant of the bottom-first method, that is, one that does not require prior plans on paper before actual construction. Of course, there is nothing to prevent such a draught on paper, at least partial, being made, either then or today. Mais pourquoi le faire du tout? Basically, the method shown will be very similar to the one presented in the thread on the boyer from the same work by Åke Rålamb. The only significant difference comes down to the slightly different positioning of the hanging guide rails, i.e. by means of a beams attached to the ship's posts, as shown in the figure below.

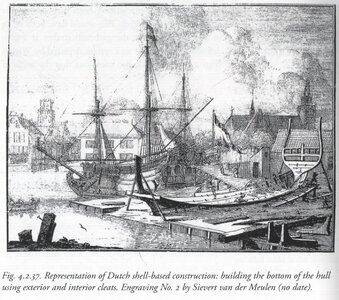

The construction sequence will not be described in its entirety, as this is already very well presented in the existing literature. While Witsen's base work is rather too hermetic to be consulted directly, the indispensable Nicolaes Witsen and Shipbuilding in the Dutch Golden Age by Ab Hoving can be particularly recommended, and on a archaeological level, for example, the excellent The Renaissance Shipwrecks from Christianshavn by Christian Lemée.

.

Last edited: