- Joined

- Jul 14, 2024

- Messages

- 15

- Points

- 48

Hi

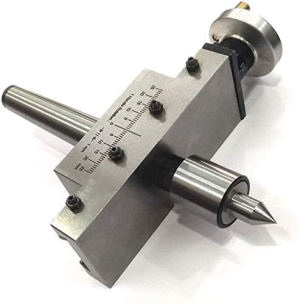

I'm UK-based, I have a 5' long work desk, and I'm looking to get a desktop lathe for shaping ship masts and other detailed work. I currently use the dowel in a cordless drill and shape with sand sandpaper method, which is a good method, but not 100% accurate. I have a good eye for detail, but I want a more precise way of working with the dowel, I have looked online and found that most desktop lathes that are a manageable weight and size, only have a max length of 150mm give or take between the centers if thats the correct terminology, which is suitable for making spars, topmast, topgallant and royal mast depending on the scale of the model.

When it comes to the lower mast, a bigger lenght is needed, can anyone recomend a manageable sized and a reasonably priced lathe as the bigger they are the more expensive. Also I expect there are many other methods that can be used to get the same result that I am not aware of so any suggestions would be welcome.

Here are the masts that I made for my Occre Revenge, they turned out pretty well.

Thanks

I'm UK-based, I have a 5' long work desk, and I'm looking to get a desktop lathe for shaping ship masts and other detailed work. I currently use the dowel in a cordless drill and shape with sand sandpaper method, which is a good method, but not 100% accurate. I have a good eye for detail, but I want a more precise way of working with the dowel, I have looked online and found that most desktop lathes that are a manageable weight and size, only have a max length of 150mm give or take between the centers if thats the correct terminology, which is suitable for making spars, topmast, topgallant and royal mast depending on the scale of the model.

When it comes to the lower mast, a bigger lenght is needed, can anyone recomend a manageable sized and a reasonably priced lathe as the bigger they are the more expensive. Also I expect there are many other methods that can be used to get the same result that I am not aware of so any suggestions would be welcome.

Here are the masts that I made for my Occre Revenge, they turned out pretty well.

Thanks