Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

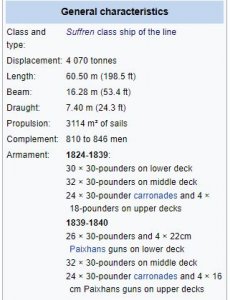

15 February 1760 - HMS Ramillies (90) driven ashore and wrecked in what is today Ramillies Cove near Salcombe, Devon

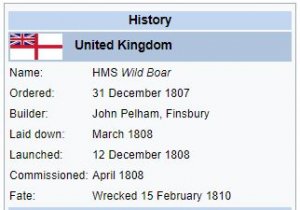

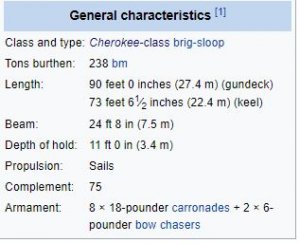

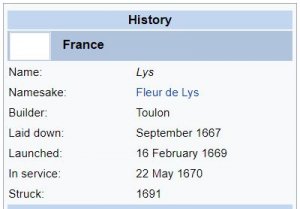

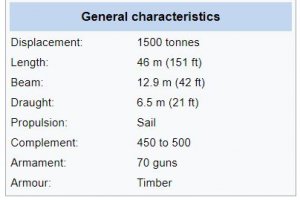

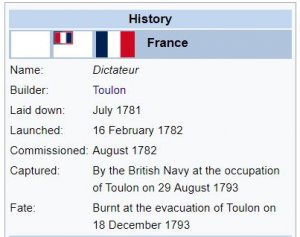

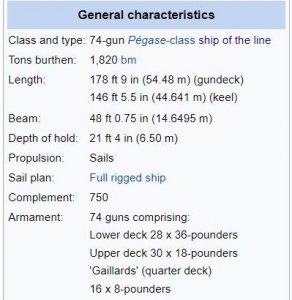

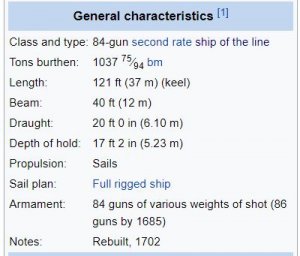

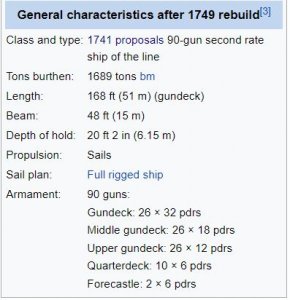

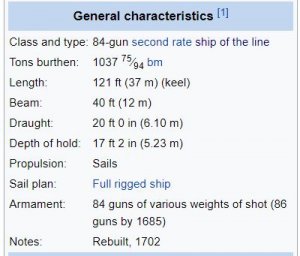

HMS Royal Katherine (HMS Ramilles after 1706) was an 84-gun second-rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, launched in 1664 at Woolwich Dockyard. Her launching was conducted by Charles II and attended by Samuel Pepys. Royal Katherine fought in the Second and Third Anglo-Dutch Wars and the War of the Grand Alliance before entering the dockyard at Portsmouth for rebuilding in 1702. She was upgraded to carry 90 guns and served in the War of the Spanish Succession during which she was renamed Ramillies in honour of John Churchill's victory at the Battle of Ramillies. She was rebuilt again in 1742–3 before serving as the flagship of the ill-fated Admiral John Byng in the Seven Years' War. Ramillies was wrecked at Bolt Tail near Hope Cove on 15 February 1760.

Launch

Royal Katherine was launched in 1664 by Charles II, an event attended by naval administrator Samuel Pepys. Pepys recorded the occasion in his diary and it was dramatised by BBC Radio 4 in 2012 as part of series 5 of The Diary of Samuel Pepys.

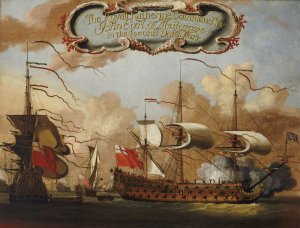

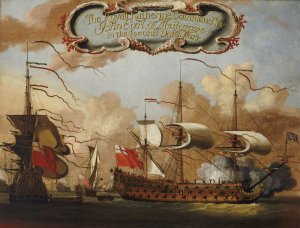

Peinture représentant le vaisseau britannique HMS Royal Katherine, lancé en 1664.

A portrait of the 'Royal Katherine', an 84-gun ship built at Woolwich in 1664 by Christopher Pett and named for Catherine [Katherine] of Braganza, the Portuguese-born queen of King Charles II. The ship took part in all the principal actions of the second and third Dutch Wars, 1665-74 and later fought against the French in King William's War, including at the Battles of Bantry Bay and La Hogue, 1692. She was originally a two-deck ship but was built up in the waist as a full 100-gun three-decker in 1673, then later reduced to 84-86 in the early 1680s. She was rebuilt as a 90-gun ship in 1700-2, renamed 'Ramillies' in 1706 and, after further rebuild, was finally wrecked in 1760. There is a characteristic Vale cartouche, ornately decorated with seashells and coral, at the top centre of the picture. This contains the inscription, 'The Royall Katherine command[e]d by John Earl of Mulgrave in the Second Dutch Warr', which is is inaccurate by modern reckoning since John Sheffield, 3rd Earl of Mulgrave, only commanded the ship during the Third Dutch War, from June to October 1672, after she was captured and then recaptured under John Chicheley at the Battle of Solebay in May, and before her 1673 enlargement as shown here. However, for reasons of Stuart loyalist propriety the inscription may ignore the first war of 1652-54, fought by the Parliamentary regime of the Interregnum. (Mulgrave served only as a volunteer at Solebay, being given command of the ship atterwards for his gallantry while she was, in effect, waiting refit. He subsequently had a more active command in the 'Captain'.) The portrait shows the 'Royal Katherine' in starboard-broadside view firing a salute, in her phase as a 100-gun first rate in the 1670s. A minor error is that only 13 middle deck guns are shown, though she had 14, with the unique feature of that furthest astern being mounted within the quarter gallery. She is flying a Union jack on her sprit top-mast as well as the red ensign and a number of pennants. A number of figures are busy on deck and a small boat is positioned at the stern with a man holding a boathook. Immediately beyond, to the left, is a gaff-rigged royal yacht in stern view (possibly intended as the 'Katherine' of 1661 from her stern carving and double quarter windows, though the two stern windows are also too small) and on the far left an additional stern view of the 'Royal Katherine'. Instead of a coat of arms she has a full-length carving of Queen Catherine on her stern, with the letters 'CR' and 'KR', (for 'Carolus Rex' and 'Katherina Regina') elsewhere in the decoration. It is possible that the painting has been slightly cut down on the left and right, but not much given that the cartouche is still central. Ships flying plain white ensigns in the background may be French, alluding to the Anglo-French alliance during the war of 1672-74. There is very little documentary information about the artist although it is known that he worked in England in the style of van de Velde and Sailmaker between 1705 and 1730. This painting is thought to be the earliest that can be attributed to him, and is likely to have been done from drawings or other images, as the apparent inclusion of the 'Katherine' yacht also suggests, since she was wrecked in 1673. It was probably painted in the 1690s, perhaps before Mulgrave became Marquess of Normanby in 1694 (and Duke of Buckingham in 1703), though use of his earlier title is not proof of that. However, the inclusion of a bobstay under the bowsprit, only introduced in the mid-1690s in English ships, suggests that decade at earliest. The picture was presumably painted for Mulgrave and was only sold from Normanby Hall by Sir Berkeley Sheffield in 1943, when the Museum purchased it. It may be the painting of the 'Royal Katherine' seen in Mulgrave's London house by Captain George Carleton and mentioned in his memoirs, first published in 1728. After describing how the ship was captured and then recaptured at Solebay in 1672, he adds: ‘This is the same Ship which the Earl of Mulgrave (afterwards Duke of Buckingham) commanded the next Sea Fight, and has caus'd to be painted in his House in St. James's Park’, though this is not correct: Mulgrave only had command to October 1672 and, by the time she next fought after rebuild as a 100-gun ship in 1673 (at Schooneveld and the Texel) George Legge had taken over. The canvas is signed 'H. Vale fec', bottom left.

Anglo-Dutch wars

Royal Katherine participated in the Second Anglo-Dutch War fighting in the Battle of Lowestoft on 13 June 1665, the Four Days' Battle from 11 June to 14 June 1666 and the St. James's Day Battle on 4 August 1666. She was scuttled in June 1667 to prevent her capture by the Dutch during the Raid on the Medway.

Refloated, Royal Katherine fought again during the Third Anglo-Dutch War of 1672–4. She was captured by the Dutch during the Battle of Solebay on 7 June 1672 but was retaken the same day. Royal Katherine was also part of the Anglo-French fleet for the Battle of Schooneveld. She saw action in the War of the Grand Alliance, fighting at the Battle of Barfleur on 29 May 1692.

Scale: 1:48. A contemporary block model of the Second Rate ‘Ramillies’ (1749), a 90-gun, three-decker ship of the line. The number ‘6’ is on the port broadside. The gun ports are painted on the side of the hull in red. The figurehead has been carved approximately to shape out of a solid block. Originally ‘Royal Katherine’, built at Woolwich in 1664, she was rebuilt in 1702 and renamed ‘Ramillies’ in 1706. Ramillies was ordered to be broken up and rebuilt 1 March 1739, [POR A/10]. She was rebuilt again at Portsmouth and launched in 1749. In 1756 it was the flagship of the Honourable John Byng at the Battle of Minorca that, fatefully, resulted in the loss of Minorca to the French and Byng’s execution on the grounds of failing to do his utmost in preventing the capture of the island (see BHC0380). The ‘Ramillies’ was wrecked in a storm off Bolt Head on the South Devon coast in 1760.

Rebuilds

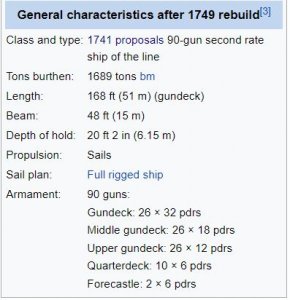

Royal Katherine was rebuilt at Portsmouth in 1702 and became a 90-gun second rate.[2] She served as the flagship of Admiral George Rooke in the War of the Spanish Succession from 1701. In 1706 she was renamed Ramillies in honour of John Churchill's victory at the Battle of Ramillies fought that year.Ramillies was rebuilt again at Portsmouth Dockyard between 30 November 1742 and 8 February 1743. She remained a 90-gun second rate in accordance with 1741 proposals of the 1719 Establishment, relaunching on 8 February.

She saw service in the Seven Years' War and was the flagship of Admiral John Byng when he failed to relieve Port Mahon and so lost the island of Minorca to the French. Byng was later controversially executed for this action.

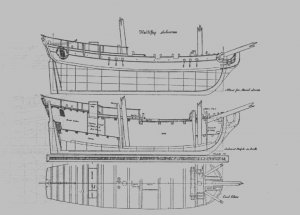

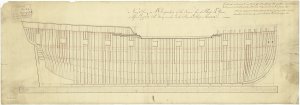

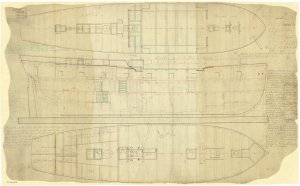

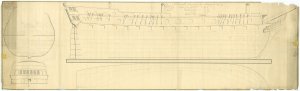

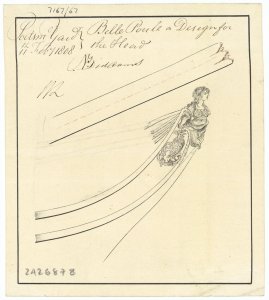

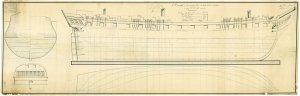

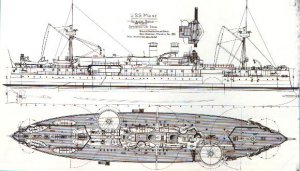

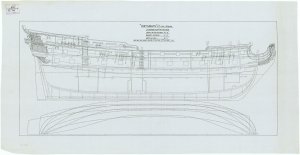

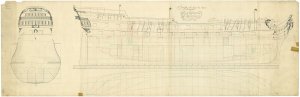

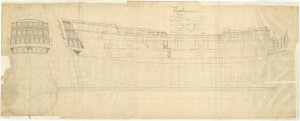

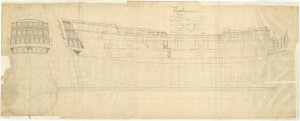

Scale 1:48. Plan showing body plan, sternboard with decoration, inboard profile with stern quarter decoration, and faint longitudinal half-breadth for 'Ramillies' (1748), a 1741 Establishment 90-gun Second Rate, three-decker. The plan illustrates the ship as she was launched at Portsmouth Dockyard.

Wreck

Ramillies was wrecked at Bolt Tail near Hope Cove on 15 February 1760.[3] The ship's master had mistaken their location as Ramillies approached the Devon shore, and the vessel was already within Hope Bay when the error was identified. There was a strong onshore wind and Ramillies' captain ordered the anchors lowered to hold the vessel fast until it could turn back to open sea, but no purchase could be found on the sandy seabed and the ship continued to drift towards the coast. After several hours she struck the cliffs beneath Bolt Tail and sank; twenty-six seamen and one midshipman survived from her crew of 850 men.[6][5] The sinking became the subject of a popular contemporary folk song, "The Loss of the Ramillies", a version of which has been recorded by the English folk band Brass Monkey.[

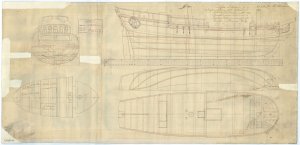

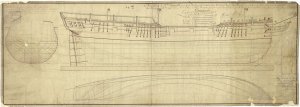

Scale 1:48. Plan showing the body plan, sternboard outline with some detail, sheer lines with quarter detail, and longitudinal half-breadth proposed for 'Ramillies' (1749), a 1741 Establishment 90-gun Second Rate, three-decker, proposed to be built at Portsmouth. The plan illustrates the ship as re-ordered to the 1741 Establishment from the 1733 Establishment design. Signed by Pierson Lock [Master Shipwright, Portsmouth Dockyard, 1742-1755 (died)].

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Royal_Katherine_(1664)

https://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/15079.html

https://collections.rmg.co.uk/colle...el-341925;browseBy=vessel;vesselFacetLetter=R

15 February 1760 - HMS Ramillies (90) driven ashore and wrecked in what is today Ramillies Cove near Salcombe, Devon

HMS Royal Katherine (HMS Ramilles after 1706) was an 84-gun second-rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, launched in 1664 at Woolwich Dockyard. Her launching was conducted by Charles II and attended by Samuel Pepys. Royal Katherine fought in the Second and Third Anglo-Dutch Wars and the War of the Grand Alliance before entering the dockyard at Portsmouth for rebuilding in 1702. She was upgraded to carry 90 guns and served in the War of the Spanish Succession during which she was renamed Ramillies in honour of John Churchill's victory at the Battle of Ramillies. She was rebuilt again in 1742–3 before serving as the flagship of the ill-fated Admiral John Byng in the Seven Years' War. Ramillies was wrecked at Bolt Tail near Hope Cove on 15 February 1760.

Launch

Royal Katherine was launched in 1664 by Charles II, an event attended by naval administrator Samuel Pepys. Pepys recorded the occasion in his diary and it was dramatised by BBC Radio 4 in 2012 as part of series 5 of The Diary of Samuel Pepys.

Peinture représentant le vaisseau britannique HMS Royal Katherine, lancé en 1664.

A portrait of the 'Royal Katherine', an 84-gun ship built at Woolwich in 1664 by Christopher Pett and named for Catherine [Katherine] of Braganza, the Portuguese-born queen of King Charles II. The ship took part in all the principal actions of the second and third Dutch Wars, 1665-74 and later fought against the French in King William's War, including at the Battles of Bantry Bay and La Hogue, 1692. She was originally a two-deck ship but was built up in the waist as a full 100-gun three-decker in 1673, then later reduced to 84-86 in the early 1680s. She was rebuilt as a 90-gun ship in 1700-2, renamed 'Ramillies' in 1706 and, after further rebuild, was finally wrecked in 1760. There is a characteristic Vale cartouche, ornately decorated with seashells and coral, at the top centre of the picture. This contains the inscription, 'The Royall Katherine command[e]d by John Earl of Mulgrave in the Second Dutch Warr', which is is inaccurate by modern reckoning since John Sheffield, 3rd Earl of Mulgrave, only commanded the ship during the Third Dutch War, from June to October 1672, after she was captured and then recaptured under John Chicheley at the Battle of Solebay in May, and before her 1673 enlargement as shown here. However, for reasons of Stuart loyalist propriety the inscription may ignore the first war of 1652-54, fought by the Parliamentary regime of the Interregnum. (Mulgrave served only as a volunteer at Solebay, being given command of the ship atterwards for his gallantry while she was, in effect, waiting refit. He subsequently had a more active command in the 'Captain'.) The portrait shows the 'Royal Katherine' in starboard-broadside view firing a salute, in her phase as a 100-gun first rate in the 1670s. A minor error is that only 13 middle deck guns are shown, though she had 14, with the unique feature of that furthest astern being mounted within the quarter gallery. She is flying a Union jack on her sprit top-mast as well as the red ensign and a number of pennants. A number of figures are busy on deck and a small boat is positioned at the stern with a man holding a boathook. Immediately beyond, to the left, is a gaff-rigged royal yacht in stern view (possibly intended as the 'Katherine' of 1661 from her stern carving and double quarter windows, though the two stern windows are also too small) and on the far left an additional stern view of the 'Royal Katherine'. Instead of a coat of arms she has a full-length carving of Queen Catherine on her stern, with the letters 'CR' and 'KR', (for 'Carolus Rex' and 'Katherina Regina') elsewhere in the decoration. It is possible that the painting has been slightly cut down on the left and right, but not much given that the cartouche is still central. Ships flying plain white ensigns in the background may be French, alluding to the Anglo-French alliance during the war of 1672-74. There is very little documentary information about the artist although it is known that he worked in England in the style of van de Velde and Sailmaker between 1705 and 1730. This painting is thought to be the earliest that can be attributed to him, and is likely to have been done from drawings or other images, as the apparent inclusion of the 'Katherine' yacht also suggests, since she was wrecked in 1673. It was probably painted in the 1690s, perhaps before Mulgrave became Marquess of Normanby in 1694 (and Duke of Buckingham in 1703), though use of his earlier title is not proof of that. However, the inclusion of a bobstay under the bowsprit, only introduced in the mid-1690s in English ships, suggests that decade at earliest. The picture was presumably painted for Mulgrave and was only sold from Normanby Hall by Sir Berkeley Sheffield in 1943, when the Museum purchased it. It may be the painting of the 'Royal Katherine' seen in Mulgrave's London house by Captain George Carleton and mentioned in his memoirs, first published in 1728. After describing how the ship was captured and then recaptured at Solebay in 1672, he adds: ‘This is the same Ship which the Earl of Mulgrave (afterwards Duke of Buckingham) commanded the next Sea Fight, and has caus'd to be painted in his House in St. James's Park’, though this is not correct: Mulgrave only had command to October 1672 and, by the time she next fought after rebuild as a 100-gun ship in 1673 (at Schooneveld and the Texel) George Legge had taken over. The canvas is signed 'H. Vale fec', bottom left.

Anglo-Dutch wars

Royal Katherine participated in the Second Anglo-Dutch War fighting in the Battle of Lowestoft on 13 June 1665, the Four Days' Battle from 11 June to 14 June 1666 and the St. James's Day Battle on 4 August 1666. She was scuttled in June 1667 to prevent her capture by the Dutch during the Raid on the Medway.

Refloated, Royal Katherine fought again during the Third Anglo-Dutch War of 1672–4. She was captured by the Dutch during the Battle of Solebay on 7 June 1672 but was retaken the same day. Royal Katherine was also part of the Anglo-French fleet for the Battle of Schooneveld. She saw action in the War of the Grand Alliance, fighting at the Battle of Barfleur on 29 May 1692.

Scale: 1:48. A contemporary block model of the Second Rate ‘Ramillies’ (1749), a 90-gun, three-decker ship of the line. The number ‘6’ is on the port broadside. The gun ports are painted on the side of the hull in red. The figurehead has been carved approximately to shape out of a solid block. Originally ‘Royal Katherine’, built at Woolwich in 1664, she was rebuilt in 1702 and renamed ‘Ramillies’ in 1706. Ramillies was ordered to be broken up and rebuilt 1 March 1739, [POR A/10]. She was rebuilt again at Portsmouth and launched in 1749. In 1756 it was the flagship of the Honourable John Byng at the Battle of Minorca that, fatefully, resulted in the loss of Minorca to the French and Byng’s execution on the grounds of failing to do his utmost in preventing the capture of the island (see BHC0380). The ‘Ramillies’ was wrecked in a storm off Bolt Head on the South Devon coast in 1760.

Rebuilds

Royal Katherine was rebuilt at Portsmouth in 1702 and became a 90-gun second rate.[2] She served as the flagship of Admiral George Rooke in the War of the Spanish Succession from 1701. In 1706 she was renamed Ramillies in honour of John Churchill's victory at the Battle of Ramillies fought that year.Ramillies was rebuilt again at Portsmouth Dockyard between 30 November 1742 and 8 February 1743. She remained a 90-gun second rate in accordance with 1741 proposals of the 1719 Establishment, relaunching on 8 February.

She saw service in the Seven Years' War and was the flagship of Admiral John Byng when he failed to relieve Port Mahon and so lost the island of Minorca to the French. Byng was later controversially executed for this action.

Scale 1:48. Plan showing body plan, sternboard with decoration, inboard profile with stern quarter decoration, and faint longitudinal half-breadth for 'Ramillies' (1748), a 1741 Establishment 90-gun Second Rate, three-decker. The plan illustrates the ship as she was launched at Portsmouth Dockyard.

Wreck

Ramillies was wrecked at Bolt Tail near Hope Cove on 15 February 1760.[3] The ship's master had mistaken their location as Ramillies approached the Devon shore, and the vessel was already within Hope Bay when the error was identified. There was a strong onshore wind and Ramillies' captain ordered the anchors lowered to hold the vessel fast until it could turn back to open sea, but no purchase could be found on the sandy seabed and the ship continued to drift towards the coast. After several hours she struck the cliffs beneath Bolt Tail and sank; twenty-six seamen and one midshipman survived from her crew of 850 men.[6][5] The sinking became the subject of a popular contemporary folk song, "The Loss of the Ramillies", a version of which has been recorded by the English folk band Brass Monkey.[

Scale 1:48. Plan showing the body plan, sternboard outline with some detail, sheer lines with quarter detail, and longitudinal half-breadth proposed for 'Ramillies' (1749), a 1741 Establishment 90-gun Second Rate, three-decker, proposed to be built at Portsmouth. The plan illustrates the ship as re-ordered to the 1741 Establishment from the 1733 Establishment design. Signed by Pierson Lock [Master Shipwright, Portsmouth Dockyard, 1742-1755 (died)].

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Royal_Katherine_(1664)

https://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/15079.html

https://collections.rmg.co.uk/colle...el-341925;browseBy=vessel;vesselFacetLetter=R