Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

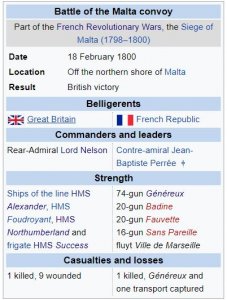

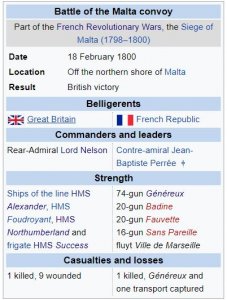

18 February 1800 - The Battle of the Malta Convoy was a naval engagement of the French Revolutionary Wars fought on 18 February 1800 during the Siege of Malta.

HMS Alexander (74), Lt. William Harrington (Acting), and HMS Success (32), Cptn. Shuldham Peard, captured Genereux (74) off Malta.

The

Battle of the Malta Convoy was a naval engagement of the

French Revolutionary Wars fought on 18 February 1800 during the

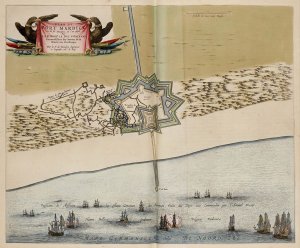

Siege of Malta. The French garrison at the city of

Valletta in

Malta had been under siege for eighteen months, blockaded on the landward side by a combined force of British, Portuguese and irregular Maltese forces and from the sea by a Royal Navy squadron under the overall command of

Lord Nelson from his base at

Palermo on

Sicily. In February 1800, the Neapolitan government replaced the Portuguese troops with their own forces and the soldiers were convoyed to Malta by Nelson and

Lord Keith, arriving on 17 February. The French garrison was by early 1800 suffering from severe food shortages, and in a desperate effort to retain the garrison's effectiveness a convoy was arranged at

Toulon, carrying food, armaments and reinforcements for Valletta under

Contre-amiral Jean-Baptiste Perrée. On 17 February, the French convoy approached Malta from the southeast, hoping to pass along the shoreline and evade the British blockade squadron.

On 18 February 1800 lookouts on the British ship

HMS Alexander sighted the French and gave chase, followed by the rest of Nelson's squadron while Keith remained off Valletta. Although most of the French ships outdistanced the British pursuit, one transport was overhauled and forced to surrender, while Perrée's flagship

Généreux was intercepted by the much smaller

frigate HMS Success. In the opening exchange of fire,

Success was badly damaged but Perrée was mortally wounded. The delay caused by the engagement allowed the main body of the British squadron to catch up the French ship and, badly outnumbered,

Généreux surrendered. Perrée died shortly after receiving his wound, and none of the supplies reached Malta, which held out for another seven months against increasing odds before surrendering on 4 September 1800.

Background

In May 1798, during the

French Revolutionary Wars, a French expeditionary force sailed from

Toulon under General

Napoleon Bonaparte.

Crossing the Mediterranean, the force captured

Malta in early June and continued southeastwards, making landfall in

Egypt on 31 June. Landing near

Alexandria, Bonaparte captured the city and advanced inland, completing the first stage of a projected campaign in Asia. The French fleet, under the command of Vice-Admiral

François-Paul Brueys D'Aigalliers was directed to anchor in

Aboukir Bay, 20 mi (32 km) northeast of Alexandria and support the army ashore. On 1 August 1798, the anchored fleet was surprised and attacked by a British fleet under Rear-Admiral

Sir Horatio Nelson. In the ensuing

Battle of the Nile, eleven of the thirteen French

ships of the line, and two of the four

frigates were captured or destroyed. Brueys was killed, and the survivors of the French fleet struggled out of the bay on 2 August, splitting up near

Crete.

Généreux sailed north to

Corfu,

encountering and capturing the British

fourth rate ship

HMS Leander en route. The other ships,

Guillaume Tell and two frigates under Contre-amirals

Pierre-Charles Villeneuve and

Denis Decrès, sailed westwards to Malta, arriving just as the island came

under siege.

On Malta, the dissolution of the

Roman Catholic Church under French rule had been extremely unpopular among the native

Maltese population. During an auction of church property on 2 September 1798, an armed uprising had begun that had forced the French garrison, commanded by General

Claude-Henri Belgrand de Vaubois, to retreat into the capital

Valletta by the end of the month. The garrison, which numbered approximately 3,000 men, had limited food stocks, and efforts to bring supplies in by sea were restricted by a squadron of British and Portuguese ships stationed off the harbour. The

blockade was under the command of Nelson, now Lord Nelson, based in

Palermo on

Sicily, and directly managed by Captain

Alexander Ball on the ship of the line

HMS Alexander. During 1799 a number of factors, including inadequate food production on Malta, lack of resources and troops caused by commitments elsewhere in the Mediterranean and the appearance of

a French fleet under Admiral

Etienne Eustache Bruix in the Western Mediterranean all contributed to lapses in the blockade. However, despite the trickle of supplies that reached the garrison, Vaubois' troops were beginning to suffer the effects of starvation and disease. Late in the year Ball went ashore assist the Maltese troops conducting the siege and was replaced in command of

Alexander by his first lieutenant, William Harrington.

In January 1800, recognising that Valletta was in danger of surrendering if it could not be resupplied, the French Navy prepared a convoy at Toulon, consisting of

Généreux, under Captain

Cyprien Renaudin, the 20-gun

corvettes Badine,

Fauvette and 16-gun

Sans Pareille and two or three transport ships. The force was under the command of Contre-amiral

Jean-Baptiste Perrée, recently

exchanged under

parole after being captured off

Acre the previous year, and was instructed to approach Valletta along the Maltese coast from the southwest with the intention of passing between the blockade squadron and the shore and entering Malta before the British could discover and intercept them. The convoy sailed on 7 February. In addition to the supplies, the convoy carried nearly 3,000 French soldiers to reinforce the garrison, an unnecessary measure that would completely counteract the replenishment of the garrison's food stocks.

While the French planned their reinforcement, the Royal Navy was preparing to replace the 500

Portuguese marines stationed on Malta with 1,200 Neapolitan troops supplied by

King Ferdinand. Nelson, who had recently been neglecting his blockade duties in favour of the politics of the Neapolitan court and in particular

Emma, Lady Hamilton, the wife of the British ambassador

Sir William Hamilton, was instructed to accompany the Neapolitan convoy. The reinforcement effort was led by Vice-Admiral

Lord Keith, Nelson's superior and overall Commander-in-Chief in the Mediterranean, in his flagship

HMS Queen Charlotte.

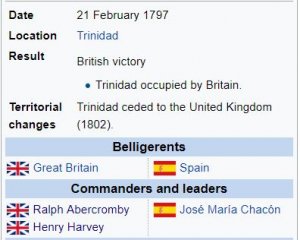

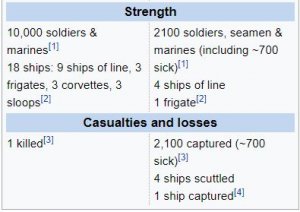

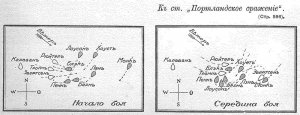

Battle

Keith's convoy arrived off Malta in the first week of February 1800 and disembarked the Neapolitan troops at

Marsa Sirocco. While stationed off Valletta on 17 February, Keith received word from the frigate

HMS Success that a French convoy was approaching the island from the direction of Sicily.

Success, commanded by Captain

Shuldham Peard, had been ordered to watch the waters off

Trapani. After discovering the French ships, which were Perrée's convoy from Toulon, Peard shadowed their approach to Malta. On receiving the message, Keith issued rapid orders for

HMS Lion to cover the channel between Malta and the offshore island of

Gozo while Nelson's flagship

HMS Foudroyant,

HMS Audacious and

HMS Northumberland joined

Alexander off the southeastern coast of Malta. Keith himself remained off Valletta in

Queen Charlotte, observing the squadron in the harbour.

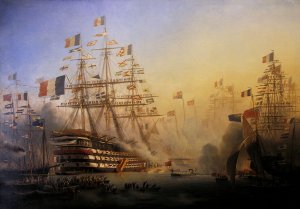

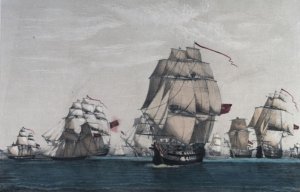

At daylight on 18 February, lookouts on

Alexander sighted the French convoy sailing along the Maltese coast towards Valletta and gave chase, with Nelson's three ships visible to seawards. At 08:00 the transport

Ville de Marseille was overhauled, and surrendered to Lieutenant Harrington's ship, but the other smaller vessels hauled up at 13:30 and made out to sea, led by

Badine.

Généreux was unable to follow as to do so would bring the French ship into action with

Alexander, and instead bore up, holding position. This station prevented

Alexander from easily coming into action, but gave Captain Peard on

Success an opportunity to close with the French ship, bringing his small vessel across the ship of the line's bow and opening a heavy fire. Peard was able to get off several broadsides against Perrée's ship before the French officers managed to turn their vessel to fire on the frigate, inflicting severe damage to Peard's rigging and masts. By this stage however, Perrée was no longer in command: a shot from the first broadside had thrown splinters into his left eye, temporarily blinding him. Remaining on deck, he called to his crew

"Ce n'est rien, mes amis, continuons notre besogne" ("It is nothing, my friends, continue with your work") and gave orders for the ship to be turned, when a cannonball from the second broadside from

Success tore his right leg off at the thigh. Perrée collapsed unconscious on the deck.

Although

Success was badly damaged and drifting, the delay had allowed Nelson's flagship

Foudroyant under Captain

Sir Edward Berry and

Northumberland under Captain

George Martin to come up to

Généreux by 16:30.

Foudroyant fired two shots at the French warship, at which point the demoralised French officers fired a single broadside at the approaching British ships and then surrendered, at 5:30. The remaining French ships had escaped seawards and eventually reached Toulon, while the British squadron consolidated their prizes and returned to Keith off Toulon. British losses in the engagement were one man killed and nine wounded, all on

Success, while French losses were confined to Perrée alone, who died of his wounds in the evening. Perrée's death was met by a mixed response in the British squadron: some regretted his death as "a gallant and capable man", while others considered him "lucky to have redeemed his honour" for violating his

parole after being captured the previous year.

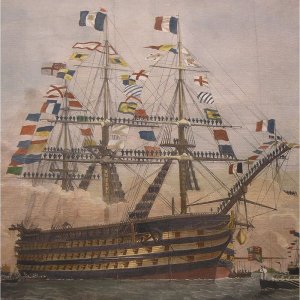

Aftermath

The French surrender was taken by Sir Edward Berry, who had last been aboard the ship as a

prisoner of war following the capture of

Leander in 1798. Nelson in particular was pleased with the capture of

Généreux, one of the two French ships of the line to have escaped the Battle of the Nile two years earlier. The French ship was only lightly damaged, and was sent to

Menorca for repairs under Lieutenant

Lord Cochrane and his brother Midshipman

Archibald Cochrane from

Queen Charlotte. During the passage, the ship was caught in a severe storm, and it was only though the leadership and personal example set by the brothers that the ship survived to reach

Port Mahon. The ship was taken into British service shortly afterwards as HMS

Genereux. Nelson was credited with the victory by Keith, although Nelson himself praised Harrington and Peard for their efforts in discovering the French convoy and bringing it to battle. The presence of the British squadron off Malta at the time of the arrival of the French convoy was largely due to luck, a factor that Ball attributed to Nelson in a letter written to Emma Hamilton shortly after the battle:

"We may truly call him a

heaven-born Admiral, upon whom fortune smiles wherever he goes. We have been carrying on the blockade of Malta sixteen months, during which time the enemy never attempted to throw in succours until this month. His Lordship arrived here the day they were within a few leagues of the island, captured the principal ships, so that not one has reached the port."

— Captain Alexander Ball, quoted in

Ernle Bradford's

Nelson: The Essential Hero, 1977,

Although pleased with the result of the engagement, Lord Keith issued strict instructions that Nelson was to remain in active command of the blockade and on no account to return to Palermo. If he had to go to port in Sicily, then he was to use

Syracuse instead. Keith then sailed to

Livorno, where his flagship was destroyed in a sudden fire that killed over 700 of the crew, although Keith himself was not on board at the time. By early March, Nelson had tired of the blockade and in defiance of Keith's instructions returned to Palermo again, leaving Captain

Thomas Troubridge of

HMS Culloden in command of the blockade squadron. In March, while Nelson was absent at Palermo, the ship of the line

Guillaume Tell, the last survivor of the Nile, attempted to break out of Malta but was

chased down and defeated by a British squadron led by Berry in

Foudroyant. Although Nelson briefly returned in April, both of the Hamiltons were aboard his ship and most of his time was spent at Marsa Sirocco in the company of Emma, with whom he was now romantically attached.

Captain

Renaudin, of

Généreux, and Joseph Allemand, of

Ville de Marseille, were both honourably acquitted during the automatic court-martial for the loss of their ships. The French Navy made no further efforts to reach Malta, and all subsequent efforts by French warships to break out the port were met by the blockade, only one frigate breaking through and reaching France. Without the supplies carried on Perrée's convoy, starvation and disease spread throughout the garrison and by the end of August 1800, French soldiers were dying at a rate of 100 a day. On 4 September, Vaubois finally capitulated, turning the island over to the British, who retained it for the next 164 years.

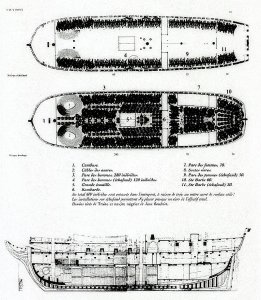

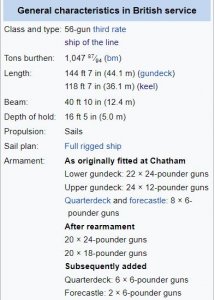

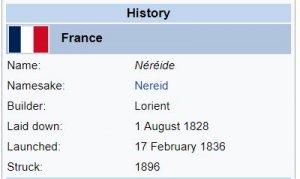

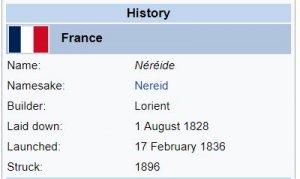

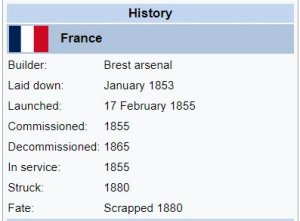

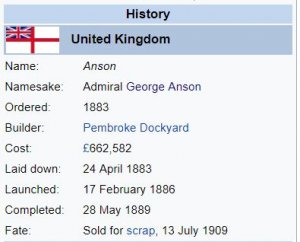

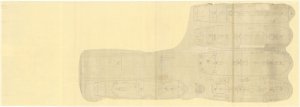

Genereux (1785) 74 (1785) – ex-French, captured 18 February 1800, prison ship 1805, broken up 1816

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_the_Malta_Convoy_(1800)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_ship_Généreux_(1785)

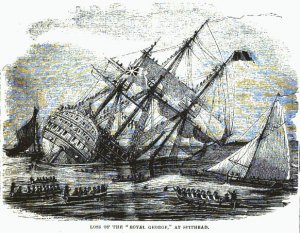

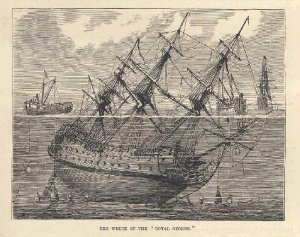

House to help the widows and children of the sailors lost in the sinking, which was the start of what eventually became the Lloyd's Patriotic Fund. The accident was commemorated in verse by the poet William Cowper:

House to help the widows and children of the sailors lost in the sinking, which was the start of what eventually became the Lloyd's Patriotic Fund. The accident was commemorated in verse by the poet William Cowper: