Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

31 March 1736 - Launch of HMS Weymouth, a 60-gun fourth rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, and in service during the War of the Austrian Succession.

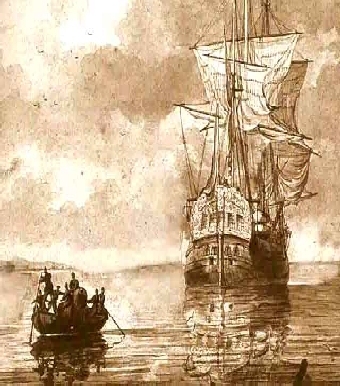

HMS Weymouth was a 60-gun fourth rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, launched in 1736 and in service during the War of the Austrian Succession. Initially stationed in the Mediterranean, she was assigned to the Navy's Caribbean fleet in 1740 and participated in Battle of Cartagena de Indias in 1741. Decommissioned later that year, she was restored to active service in the Caribbean in 1744. A navigational error on 16 February 1745 brought her too close to the shore of Antigua, where she was wrecked upon a submerged reef. Three of Weymouth's officers were subsequently found guilty of negligence, with two required to pay substantial fines and the third sentenced to a two-year jail term.

Description

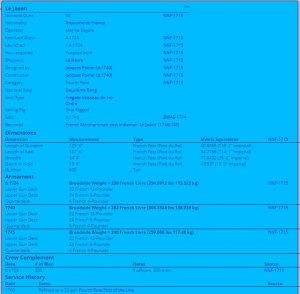

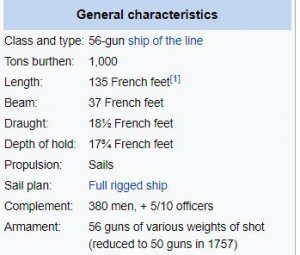

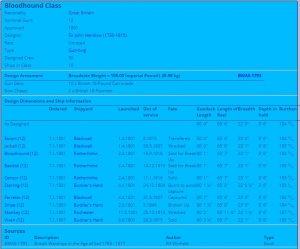

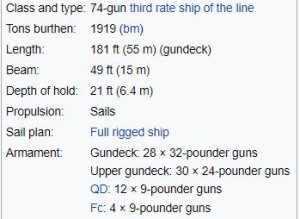

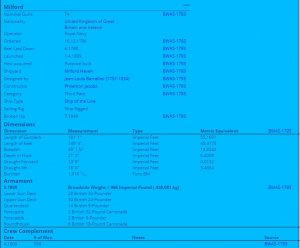

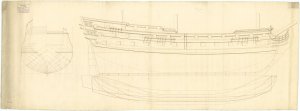

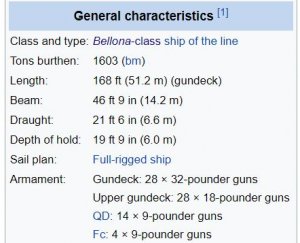

Weymouth was designed according to the 1733 proposals of the 1719 Establishment of dimensions. As built, she was 144 ft 5 in (44.0 m) long with a 116 ft 10 in (35.6 m) keel, a beam of 41 ft 5 in (12.62 m), and a hold depth of 16 ft 11 in (5.2 m). She was armed with twenty-four 24-pounder cannons located along her gundeck, supported by 26 nine-pounders on the upper deck and ten 6-pounders ranged along the quarterdeck and the forecastle. The designated complement was 400, comprising four commissioned officers – a captain and three lieutenants – overseeing 63 warrant and petty officers, 219 naval ratings, 67 Marines and 47 servants and other ranks. The 47 servants and other ranks provided for in the ship's complement consisted of 30 personal servants and clerical staff, six assistant carpenters, two assistant sailmakers, a steward's mate and eight widow's men. Weymouth's marines were headed by a captain and second lieutenant, with four non-commissioned officers, a drummer boy and 60 private soldiers.

Construction and career

Weymouth, named after the eponymous port, was ordered on 6 January 1733. She was laid down in September at Plymouth Dockyard and was launched on 31 March 1736. Completed on 27 July 1739 at the cost of £14,963, she commissioned under the command of Captain Lord Aubrey Beauclerk, but he was replaced by Captain Thomas Trefusis in July and the ship was sent to the Mediterranean. The following year the ship was commanded by Captain Charles Knowles and participated in the Battle of Cartagena de Indias in March 1741.

Loss

Weymouth was recommissioned for active service on 10 June 1744, under the command of Captain Warwick Calmady. Calmady had recently transferred aboard from the sixth-rateHMS Lively which had been paid off at Spithead the previous day. He brought most of Lively's crew with him, as Weymouth was short-handed while in ordinary. the next four months were spent in fitting out Weymouth for action at sea. She put to sea on 18 November 1744 to join a squadron under vice-admiral Thomas Davers, which was escorting a merchant convoy destined for the Caribbean.

On 17 February 1745, shortly before 01:00, Weymouth grounded after having sailed from English Harbour, Antigua on 13 February. All her guns and stores were removed, before Weymouth finally broke up on 22 February. Her commanding officer, Captain Warwick Calmady, was court-martialed over the loss on 18—19 February, and acquitted. The pilot who was embarked on Weymouth was sentenced to two years at the Marshalsea prison.

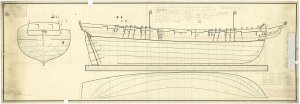

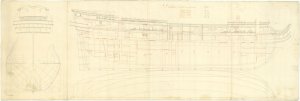

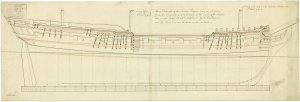

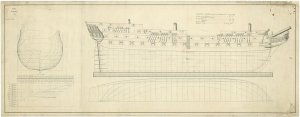

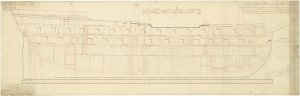

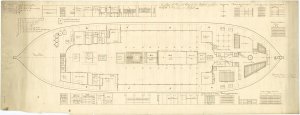

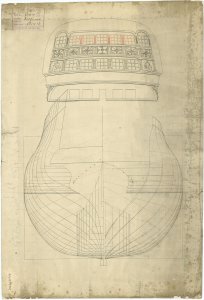

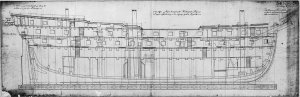

Scale: 1:48. Plan showing the body plan, sheer lines, and longitudinal half-breadth for Dragon (1736), Weymouth (1736), and with alterations for Nottingham (1745), Medway (1742), and Dreadnought (1742), all 1733 Establishment 60-gun Third (later Fourth) Rate, two-decker.

Scale: 1:48. Plan showing the body plan, sheer lines, and longitudinal half-breadth for Weymouth (1736) and Dragon (1736). The plan includes the ticked outlines aft for Medway (1742) and Dreadnought (1742) prior to alterations to the floor. The plan also illustrates the alterations forward and to the gunports for Nottingham (1745). All the ships were 1733 Establishment 60-gun Third (later Fourth) Rate, two-deckers.

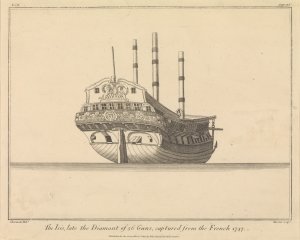

Medway' (1742), a 60-gun two-decker ship of the line, built in 'bread and butter' construction and finished in the Georgian style. Model is partially decked, rigged (circa 1763) and fully equipped including anchors and all associated gear, the whole model mounted on its original veneered baseboard. Built by Elias Bird of Rotherhithe, the 'Medway’ had a gun deck length of 144 feet by 42 feet in the beam and a tonnage of 1080 burden. It spent the early part of its career as part of a small fleet patrolling the Indian Ocean and took part in an indecisive action against the French Squadron off the Coromandel Coast in 1746. The 'Medway’ was eventually sunk as part of a breakwater in Trincomalee in 1749.

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

31 March 1736 - Launch of HMS Weymouth, a 60-gun fourth rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, and in service during the War of the Austrian Succession.

HMS Weymouth was a 60-gun fourth rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, launched in 1736 and in service during the War of the Austrian Succession. Initially stationed in the Mediterranean, she was assigned to the Navy's Caribbean fleet in 1740 and participated in Battle of Cartagena de Indias in 1741. Decommissioned later that year, she was restored to active service in the Caribbean in 1744. A navigational error on 16 February 1745 brought her too close to the shore of Antigua, where she was wrecked upon a submerged reef. Three of Weymouth's officers were subsequently found guilty of negligence, with two required to pay substantial fines and the third sentenced to a two-year jail term.

Description

Weymouth was designed according to the 1733 proposals of the 1719 Establishment of dimensions. As built, she was 144 ft 5 in (44.0 m) long with a 116 ft 10 in (35.6 m) keel, a beam of 41 ft 5 in (12.62 m), and a hold depth of 16 ft 11 in (5.2 m). She was armed with twenty-four 24-pounder cannons located along her gundeck, supported by 26 nine-pounders on the upper deck and ten 6-pounders ranged along the quarterdeck and the forecastle. The designated complement was 400, comprising four commissioned officers – a captain and three lieutenants – overseeing 63 warrant and petty officers, 219 naval ratings, 67 Marines and 47 servants and other ranks. The 47 servants and other ranks provided for in the ship's complement consisted of 30 personal servants and clerical staff, six assistant carpenters, two assistant sailmakers, a steward's mate and eight widow's men. Weymouth's marines were headed by a captain and second lieutenant, with four non-commissioned officers, a drummer boy and 60 private soldiers.

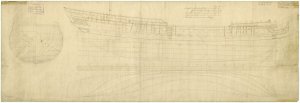

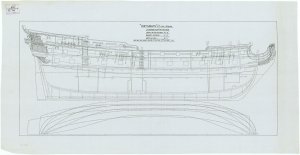

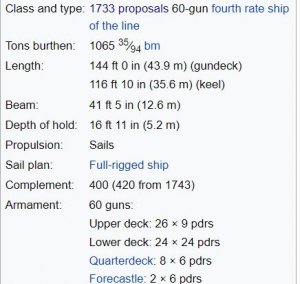

| Scale: 1:48. A modern plan showing the inboard profile with figurehead, and longitudinal half-breadth for Weymouth (1736), a 1733 Establishment 60-gun Fourth Rate, two-decker, possibly as built in 1736. |

Construction and career

Weymouth, named after the eponymous port, was ordered on 6 January 1733. She was laid down in September at Plymouth Dockyard and was launched on 31 March 1736. Completed on 27 July 1739 at the cost of £14,963, she commissioned under the command of Captain Lord Aubrey Beauclerk, but he was replaced by Captain Thomas Trefusis in July and the ship was sent to the Mediterranean. The following year the ship was commanded by Captain Charles Knowles and participated in the Battle of Cartagena de Indias in March 1741.

Loss

Weymouth was recommissioned for active service on 10 June 1744, under the command of Captain Warwick Calmady. Calmady had recently transferred aboard from the sixth-rateHMS Lively which had been paid off at Spithead the previous day. He brought most of Lively's crew with him, as Weymouth was short-handed while in ordinary. the next four months were spent in fitting out Weymouth for action at sea. She put to sea on 18 November 1744 to join a squadron under vice-admiral Thomas Davers, which was escorting a merchant convoy destined for the Caribbean.

On 17 February 1745, shortly before 01:00, Weymouth grounded after having sailed from English Harbour, Antigua on 13 February. All her guns and stores were removed, before Weymouth finally broke up on 22 February. Her commanding officer, Captain Warwick Calmady, was court-martialed over the loss on 18—19 February, and acquitted. The pilot who was embarked on Weymouth was sentenced to two years at the Marshalsea prison.

Scale: 1:48. Plan showing the body plan, sheer lines, and longitudinal half-breadth for Dragon (1736), Weymouth (1736), and with alterations for Nottingham (1745), Medway (1742), and Dreadnought (1742), all 1733 Establishment 60-gun Third (later Fourth) Rate, two-decker.

Scale: 1:48. Plan showing the body plan, sheer lines, and longitudinal half-breadth for Weymouth (1736) and Dragon (1736). The plan includes the ticked outlines aft for Medway (1742) and Dreadnought (1742) prior to alterations to the floor. The plan also illustrates the alterations forward and to the gunports for Nottingham (1745). All the ships were 1733 Establishment 60-gun Third (later Fourth) Rate, two-deckers.

Medway' (1742), a 60-gun two-decker ship of the line, built in 'bread and butter' construction and finished in the Georgian style. Model is partially decked, rigged (circa 1763) and fully equipped including anchors and all associated gear, the whole model mounted on its original veneered baseboard. Built by Elias Bird of Rotherhithe, the 'Medway’ had a gun deck length of 144 feet by 42 feet in the beam and a tonnage of 1080 burden. It spent the early part of its career as part of a small fleet patrolling the Indian Ocean and took part in an indecisive action against the French Squadron off the Coromandel Coast in 1746. The 'Medway’ was eventually sunk as part of a breakwater in Trincomalee in 1749.

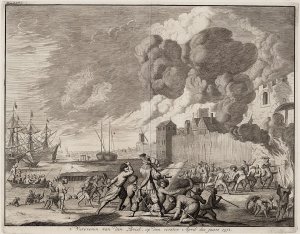

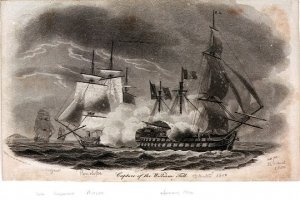

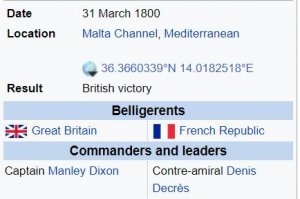

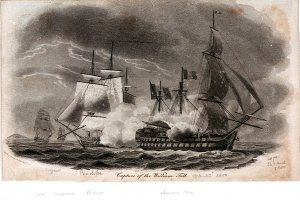

of the capture of Guillaume Tell was immediately passed to Vaubois by the British besiegers, along with a demand that he surrender the island. The French general, despite dwindling food supplies, refused, stating "Cette place est en trop bon état, et je suis moi-même trop jaloux de bien servir mon pays et de conserver mon honneur, pour écouter vos propositions." ("This place is in too good a situation, and I am too conscious of the service of my country and my honour, to listen to your proposals"). Despite Vaubois' defiance, the garrison was rapidly starving, and although the French commander resisted until 4 September, he was eventually forced to surrender Valletta and all of its military equipment to the British.

of the capture of Guillaume Tell was immediately passed to Vaubois by the British besiegers, along with a demand that he surrender the island. The French general, despite dwindling food supplies, refused, stating "Cette place est en trop bon état, et je suis moi-même trop jaloux de bien servir mon pays et de conserver mon honneur, pour écouter vos propositions." ("This place is in too good a situation, and I am too conscious of the service of my country and my honour, to listen to your proposals"). Despite Vaubois' defiance, the garrison was rapidly starving, and although the French commander resisted until 4 September, he was eventually forced to surrender Valletta and all of its military equipment to the British.