Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

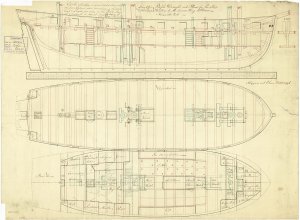

1 April 1813 - USS Gallatin (1807), a post-Revolutionary War sailing vessel that the U.S. Department of the Treasury purchased at Norfolk, Virginia, for the Revenue Cutter Service was destroyed by an explosion on board

USS Gallatin (1807) was a post-Revolutionary War sailing vessel that the U.S. Department of the Treasury purchased at Norfolk, Virginia, for the Revenue Cutter Service in December 1807. An explosion on board destroyed her in 1813.

Revenue cutter operations

On 5 December 1807, in Norfolk, Daniel McNeil paid US$$9,432.93 for the Gallatin. He was her first master and he sailed her to Charleston, South Caroline to assume revenue cutter services. His master's commission for the State of South Carolina bears the same date.

In February 1808 Gallatin arrested the schooner Kitty for violating the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves of March 1807. She had 32 slaves on board and the seizure gave rise to a court case. The court voided the seizure on the grounds that the law was passed after Kitty had left the United States and her captain could not have known of its passage.

War of 1812 service

America's declaration of war, in mid-June 1812, was followed shortly by the Enemy Trade Act of 1812 on 6 July, which employed similar restrictions as previous legislation such as the Embargo Act of 1807, including prohibiting all trade with Great Britain; the 1812 Act was as ineffective as prior acts.

On 7 July 1812, Norfolk native and experienced merchant Edward Herbert, of Norfolk, and an experienced merchant captain, replaced McNeil as master of Gallatin. Then in August 1812 the Treasury transferred Gallatin from Charleston back to Norfolk.

On 1 August 1812, Gallatin, under the command of Daniel McNeil, captured the brig General Blake, which was sailing from London to Amelia Island. General Blake was flying the Spanish flag and carried an illegal cargo, including African slaves. The capture was adjudicated in Charleston, South Carolina. A French privateer captured the General Blake as she departed Charleston in January 1813.

According to a newspaper report, Gallatin captured a British letter of marque on 6 August as the British vessel was sailing to Jamaica. However, the New York Evening Post later declared the report false, and likely referencing the capture of the General Blake.

On 12 August Gallatin escorted the British schooner HMS Whiting out of American waters at Hampton Roads. The Norfolk privateer Dash had captured Whiting, which had been bringing official dispatches to the US government from Britain and which was unaware of the outbreak of war. The US government ordered the release of Whiting. Unfortunately for the schooner, the French privateer Diligent or Diligence captured Whiting shortly after she was released.

On 2 September Gallatin escorted the ship Tom Hazard into Norfolk. The privateer Comet had captured her and the master of Comet had kept the ship's papers and manifest before releasing her. As far as McNeil was concerned, Tom Hazardwas carrying an illegal cargo of British goods.

Then on 10 October, Gallatin detained the Active, of London, and the Georgiana, of Liverpool, for violation of the Enemy Trade Act. Nine days later, while on a cruise, Gallatin sighted a British warship near Savannah, Georgia.

John Hubbard Silliman replaced Herbert as master after Gallatin returned to Charleston. His commission as a revenue cutter master in the State of South Carolina is dated 22 October 1812.

On 7 November, Silliman sailed Gallatin in company with the privateer Saucy Jack to attempt to intercept the British privateer Caledonia. They were unsuccessful.

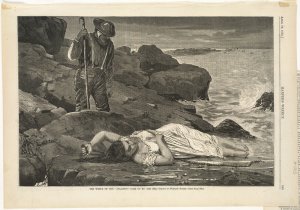

In the new year, on 27 March 1813, the captain of the schooner Malaparte published a letter thanking Silliman and his men for helping to save his schooner's cargo after she went ashore near Savannah.

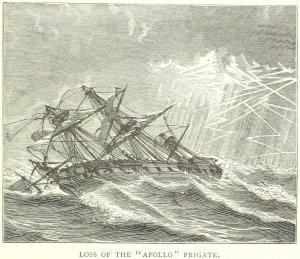

Fate

Gallatin sank on 1 April in the harbour at Charleston, South Carolina. The cause of the sinking was an explosion that killed three men and seriously wounded five more.

Gallatin had returned from a cruise the day before and Silliman had gone ashore, leaving orders that the crew clean the muskets and pistols. They were engaged on this task when the ship's powder room exploded. The cause of the explosion was never determined.

Post script

On 31 March 1814 a Charleston newspaper reported that salvors had built a diving bell to retrieve ordnance and equipment from the sunken cutter.

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

southcarolina1670.wordpress.com

southcarolina1670.wordpress.com

1 April 1813 - USS Gallatin (1807), a post-Revolutionary War sailing vessel that the U.S. Department of the Treasury purchased at Norfolk, Virginia, for the Revenue Cutter Service was destroyed by an explosion on board

USS Gallatin (1807) was a post-Revolutionary War sailing vessel that the U.S. Department of the Treasury purchased at Norfolk, Virginia, for the Revenue Cutter Service in December 1807. An explosion on board destroyed her in 1813.

Revenue cutter operations

On 5 December 1807, in Norfolk, Daniel McNeil paid US$$9,432.93 for the Gallatin. He was her first master and he sailed her to Charleston, South Caroline to assume revenue cutter services. His master's commission for the State of South Carolina bears the same date.

In February 1808 Gallatin arrested the schooner Kitty for violating the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves of March 1807. She had 32 slaves on board and the seizure gave rise to a court case. The court voided the seizure on the grounds that the law was passed after Kitty had left the United States and her captain could not have known of its passage.

War of 1812 service

America's declaration of war, in mid-June 1812, was followed shortly by the Enemy Trade Act of 1812 on 6 July, which employed similar restrictions as previous legislation such as the Embargo Act of 1807, including prohibiting all trade with Great Britain; the 1812 Act was as ineffective as prior acts.

On 7 July 1812, Norfolk native and experienced merchant Edward Herbert, of Norfolk, and an experienced merchant captain, replaced McNeil as master of Gallatin. Then in August 1812 the Treasury transferred Gallatin from Charleston back to Norfolk.

On 1 August 1812, Gallatin, under the command of Daniel McNeil, captured the brig General Blake, which was sailing from London to Amelia Island. General Blake was flying the Spanish flag and carried an illegal cargo, including African slaves. The capture was adjudicated in Charleston, South Carolina. A French privateer captured the General Blake as she departed Charleston in January 1813.

According to a newspaper report, Gallatin captured a British letter of marque on 6 August as the British vessel was sailing to Jamaica. However, the New York Evening Post later declared the report false, and likely referencing the capture of the General Blake.

On 12 August Gallatin escorted the British schooner HMS Whiting out of American waters at Hampton Roads. The Norfolk privateer Dash had captured Whiting, which had been bringing official dispatches to the US government from Britain and which was unaware of the outbreak of war. The US government ordered the release of Whiting. Unfortunately for the schooner, the French privateer Diligent or Diligence captured Whiting shortly after she was released.

On 2 September Gallatin escorted the ship Tom Hazard into Norfolk. The privateer Comet had captured her and the master of Comet had kept the ship's papers and manifest before releasing her. As far as McNeil was concerned, Tom Hazardwas carrying an illegal cargo of British goods.

Then on 10 October, Gallatin detained the Active, of London, and the Georgiana, of Liverpool, for violation of the Enemy Trade Act. Nine days later, while on a cruise, Gallatin sighted a British warship near Savannah, Georgia.

John Hubbard Silliman replaced Herbert as master after Gallatin returned to Charleston. His commission as a revenue cutter master in the State of South Carolina is dated 22 October 1812.

On 7 November, Silliman sailed Gallatin in company with the privateer Saucy Jack to attempt to intercept the British privateer Caledonia. They were unsuccessful.

In the new year, on 27 March 1813, the captain of the schooner Malaparte published a letter thanking Silliman and his men for helping to save his schooner's cargo after she went ashore near Savannah.

Fate

Gallatin sank on 1 April in the harbour at Charleston, South Carolina. The cause of the sinking was an explosion that killed three men and seriously wounded five more.

Gallatin had returned from a cruise the day before and Silliman had gone ashore, leaving orders that the crew clean the muskets and pistols. They were engaged on this task when the ship's powder room exploded. The cause of the explosion was never determined.

Post script

On 31 March 1814 a Charleston newspaper reported that salvors had built a diving bell to retrieve ordnance and equipment from the sunken cutter.

USRC Gallatin (1807) - Wikipedia

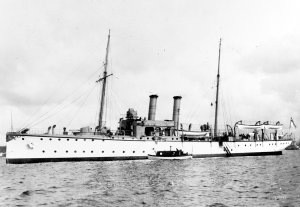

Archaeologists seek cutter lost 200 years ago

A research team led by underwater archaeologists from the South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology began searching this week for a revenue cutter that exploded in Charleston Harbor …