Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

3 February 1509 – The Battle of Diu - Part I

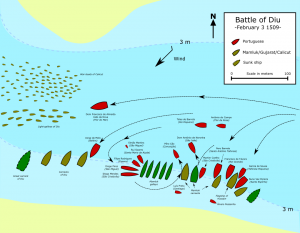

The Portuguese navy defeats a joint fleet of the Ottoman Empire, the Republic of Venice, the Sultan of Gujarat, the Mamlûk Burji Sultanate of Egypt, the Zamorin of Calicut, and the Republic of Ragusa at the Battle of Diu in Diu, India.

The

Battle of Diu was a

naval battle fought on 3 February 1509 in the

Arabian Sea, in the port of

Diu, India, between the

Portuguese Empire and a joint fleet of the

Sultan of Gujarat, the

Mamlûk Burji Sultanate of Egypt, the

Zamorin of

Calicut with support of the

Republic of Venice.

The Portuguese victory was critical: the great Muslim alliance were soundly defeated, easing the Portuguese strategy of controlling the

Indian Ocean to route trade down the

Cape of Good Hope, circumventing the traditional

spice route controlled by the

Arabs and the

Venetians through the Red Sea and Persian Gulf. After the battle, Portugal rapidly captured key ports in the Indian Ocean like

Goa,

Ceylon,

Malacca and

Ormuz, crippling the

Mamluk Sultanate and the

Gujarat Sultanate, greatly assisting the growth of the

Portuguese Empire and establishing its trade dominance for almost a century, until it was lost at the

Battle of Swally during the

Dutch-Portuguese War, over a hundred years after.

The Battle of Diu was a battle of annihilation alike

Lepanto and

Trafalgar, and one of the most important of world naval history, for it marks the beginning of European dominance over Asian seas that would last until

World War Two.

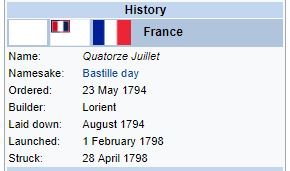

Fort Diu

Fort Diu, built in 1535

Background

Just two years after

Vasco da Gama reached India by sea, the Portuguese realized that the prospect of developing trade such as that which they had practiced in West Africa had become an impossibility, due to the opposition of Muslim merchant elites in the western coast of India, who incited attacks against Portuguese

feitorias, ships and agents, sabotaged Portuguese diplomatical efforts, and led the

massacre of the Portuguese in Calicut in 1500.

Thus, the Portuguese signed an alliance with a rebellious vassal of Calicut instead, the raja of

Cochin, who invited them to establish

a headquarters. The Zamorin of Calicut invaded Cochin in response, but the Portuguese were able to devastate the lands and cripple the trade of Calicut, which at the time served as the main exporter of spices back to Europe, through the

Red Sea. In December 1504, the Portuguese destroyed the Zamorin's yearly merchant fleet bound to Egypt, laden with spices.

When

King Manuel I of Portugal received news of these developments, he decided to nominate Dom Francisco de Almeida as the first viceroy of India with expressed orders not just limited to safeguarding Portuguese

feitorias, but also to curb hostile Muslim shipping.

[8] Dom Francisco departed from Lisbon in March 1505 with twenty ships and his 20-year-old son, Dom Lourenço, who was himself nominated

capitão-mor do mar da Índia or captain-major of the sea of India.

Portuguese intervention was seriously disrupting Muslim

trade in the Indian Ocean, threatening

Venetian interests as well, as the Portuguese became able to undersell the Venetians in the spice trade in Europe.

Unable to oppose the Portuguese, the Muslim communities of traders in India as well as the sovereign of

Calicut, the

Zamorin, sent envoys to Egypt pleading for aid against the Portuguese.

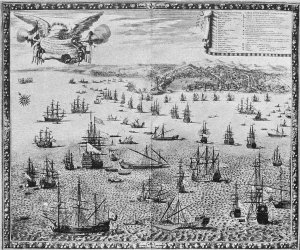

Portuguese presence in the Indian Ocean around early 16th century

The Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt

16th-century Mamluks

The

Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt was, in the beginning of the 16th century, the main middleman between the spice producing regions of India, and the Venetian buyers in the Mediterranean, mainly in

Alexandria, who then sold the spices in Europe at a great profit. Egypt was otherwise mostly an agrarian society with little ties to the sea.

Venice broke diplomatic relations with Portugal and started looking for ways to counter its intervention in the Indian Ocean, sending an ambassador to the Mamluk court and suggested that "rapid and secret remedies" be taken against the Portuguese.

Mamluk soldiers had little expertise in naval warfare, so the Mamluk Sultan,

Al-Ashraf Qansuh al-Ghawri requested Venetian support, in exchange for lowering tariffs to facilitate competition with the Portuguese. Venice supplied the Mamluks with Mediterranean-type carracks and war galleys manned by Greek sailors, which Venetian

shipwrights helped disassemble in

Alexandria and reassemble on the Suez. The galleys could mount cannon fore and aft, but not along the gunwales because the guns would interfere with the rowers. The native ships (

dhows), with their sewn wood planks, could carry only very light guns.

Command of the expedition was entrusted to a

Kurdish Mamluk, former governor of Jeddah Amir Hussain Al-Kurdi,

Mirocem in Portuguese. The expedition (referred to by the Portuguese the generic term "the

rumes") included not only Egyptian Mamluks, but also a large number of Turkish,

Nubian and Ethiopian mercenaries as well as Venetian gunners Hence, most of the coalition's artillery were archers, whom the Portuguese could easily outshoot.

The fleet left Suez in November 1505, 1,100 men strong. They were ordered to fortify

Jeddah against a possible Portuguese attack and quell rebellions around Suakin and Mecca. They had to spend the monsoon season on the island of

Kamaran and called at

Aden at the tip of the

Red Sea, where they got involved in costly local politics with the

Tahirid Emir, before finally crossing the Indian Ocean. Hence only in September 1507 did they reach

Diu, a city at the mouth of the

Gulf of Khambhat, in a journey that could have taken as little as a month to complete at full sail.

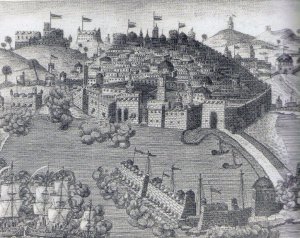

Diu and Malik Ayyaz

19th-century map of

Chaul

At the time of the arrival of the Portuguese in India, the Gujarati were the main long distance dealers in the Indian Ocean, and an essential intermediary in east–west trade, between

Egypt and

Malacca, mostly trading cloths and spices. In the 15th century, the Sultan of Gujarat nominated

Malik Ayyaz, a former bowman and slave of possible

Georgian or

Dalmatian origin, as the governor of Diu. A cunning and pragmatical ruler, Malik Ayyaz turned the city into the main port of Gujarat (known to the Portuguese as

Cambaia) and one of the main entrepôts between India and the

Persian Gulf, avoiding Portuguese hostility by pursuing a policy of appeasement and even alignment – up until Hussain unexpectedly sailed into Diu.

Malik Ayyaz received Hussain well, but besides the Zamorin of Calicut, no other rulers of the Indian subcontinent were forthcoming against the Portuguese, unlike what the Muslim envoys to Egypt had promised. Ayyaz himself realized the Portuguese were a formidable naval force whom he did not wish to antagonize. He could not, however, reject Hussain for fear of retaliation from the powerful Sultan of Gujarat – besides obviously Hussain's own forces now within the city. Caught in a double bind, Ayyaz decided to only cautiously support Hussain.

The Battle of Chaul

Main article:

Battle of Chaul

In March 1508, Hussain's and Ayyaz's fleets sailed south and clashed with Portuguese ships in a three-day naval engagement within the harbour of Chaul. The Portuguese commander was the captain-major of the seas of India,

Lourenço de Almeida, tasked with overseeing the loading of allied merchant ships in that city and escort them back to Cochin.

Although the Portuguese were caught off-guard (the distinctively European-like ships of Hussein were at first thought to belong to the expedition of Afonso de Albuquerque, assigned to the Arabian Coast), the battle ended as a

Pyrrhic victory for the Muslims, who suffered too many losses to be able to proceed towards the

Portuguese headquarters in Cochin. Despite fortuitously sinking the Portuguese flagship, the rest of the Portuguese fleet escaped, while Hussain himself barely survived the encounter because of the unwilling committal of Malik Ayyaz to the battle. Hussain was left with no other choice but to return to Diu with Malik Ayyaz and prepare for a Portuguese retaliation. Hussain reported this battle back to Cairo as a great victory; however, the

Mirat Sikandari, a contemporary

Persian account of the Kingdom of Gujarat, details this battle as a minor skirmish.

Nevertheless, among the dead was the viceroy's own son, Lourenço, whose body was never recovered, despite the best efforts of Malik Ayyaz to retrieve it for the Portuguese viceroy.

Portuguese preparations

Dom Francisco de Almeida, first viceroy of India

Upon hearing in Cochin of the death of his only son, Dom Francisco de Almeida was heart-stricken, and retired to his quarters for three days, unwilling to see anyone. The presence of a Mamluk fleet in India posed a grave threat to the Portuguese, but the viceroy now sought to personally exact revenge for the death of his son at the hands of

Mirocem, supposedly having said that "he who ate the chick must also eat the rooster or pay for it".

Nevertheless, the

monsoon was approaching, and with it the storms that inhibited all navigation in the Indian Ocean until September. Only then could the viceroy call back all available Portuguese ships for repairs in dry dock and assemble his forces in Cochin.

Before they could depart though, on 6 December 1508

Afonso de Albuquerque arrived in

Cannanore from the

Persian Gulf with orders from the King of Portugal to replace Almeida as governor. Dom Francisco had a personal vendetta against Albuquerque, as the latter had been assigned to the Arabian Coast specifically to prevent Muslim navigation from entering or leaving the Red Sea. Yet his intentions of personally destroying the Muslim fleet in retaliation of his son's death became such a personal issue that he refused to allow his appointed successor take office. In doing so, the viceroy was in official rebellion against royal authority, and would rule Portuguese India for another year as such.

On 9 December, the Portuguese fleet departed for Diu.

The Armada da Índia on the move

From Cochin, the Portuguese first passed by Calicut, hoping to intercept the Zamorin's fleet, but it had already left for Diu. The armada then anchored in

Baticala, to quell a dispute between its king and a local Hindu privateer allied to the Portuguese,

Timoja. In

Honavar, the Portuguese met with Timoja himself, who informed the viceroy of enemy movements. While there, the Portuguese galleys destroyed a fleet of raiders belonging to the Zamorin of Calicut.

At Angediva, the fleet fetched freshwater and Dom Francisco met with an envoy of Malik Ayyaz, though the details of such rendezvous are unknown. While there, the Portuguese were attacked by oar ships of the city of

Dabul, unprovoked.

Dabul

From

Angediva, the Portuguese set sail to

Dabul, an important fortified port city belonging to the

Sultanate of Bijapur. The captain of the galley

São Miguel, Paio de Sousa, decided to investigate the harbour and put to shore, but he was ambushed by a force of about 6,000 men and was killed, along with other Portuguese. Two days later, the viceroy led his heavily armoured forces ashore and crushed the garrison stationed by the riverbank in an amphibious pincer attack. Dabul paid dearly the act of provocation, as per the viceroy's orders the city was then razed, the surrounding riverside settlements devastated and almost all their inhabitants killed, along with the cattle and even stray dogs in retaliation.

According to

Fernão Lopes de Castanheda, the sack of Dabul gave rise to a 'curse' on the western coast of India, where one might say: "may the wrath of the franks befall you".

Chaul and Bombay

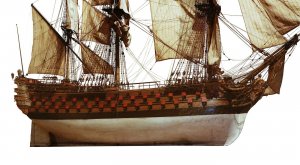

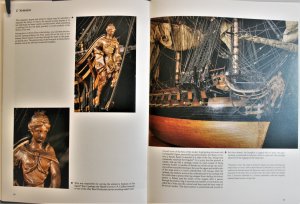

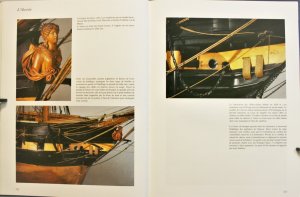

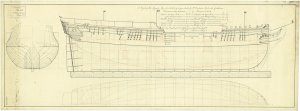

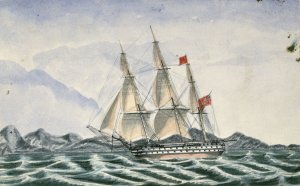

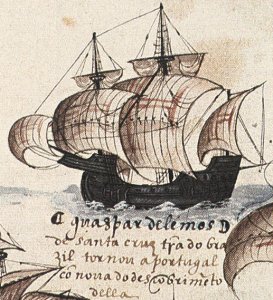

Portuguese

nau. With fore and aft castles integrated in the hull and a deeper draught meant to withstand long trans-oceanic voyages, Portuguese carracks were some of the most seaworthy ships of their time.

From Dabul, the Portuguese called at Chaul, where Dom Francisco ordered the governor of the town to prepare a tribute to be collected on the return from Diu. Moving towards Mahim, close to Bombay, the Portuguese found the town deserted.

At Bombay, Dom Francisco received a letter from Malikk Ayyaz. Doubtlessly aware of the danger facing his city, he wrote to appease the viceroy, stating that he had the prisoners and how bravely his son had fought, adding a letter from the Portuguese prisoners stating that they were well treated. The viceroy answered Malik Ayyaz (referred to as Meliqueaz in Portuguese) with a respectful but menacing letter, stating his intention of revenge, that they had better join all forces and prepare to fight or he would destroy Diu:

I the Viceroy say to you, honored Meliqueaz captain of Diu, that I go with my knights to this city of yours, to take the people who were welcomed there, who in Chaul fought my people and killed a man who was called my son, and I come with hope in God of Heaven to take revenge on them and on those who assist them, and if I don't find them I will take your city, to pay for everything, and you, for the help you have done at Chaul. This I tell you, so that you are well aware that I go, as I am now on this island of

Bombay, as he will tell you the one who carries this letter.

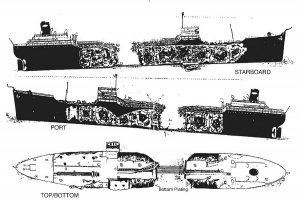

damage to the V.A. Fogg from the USCG accident report

damage to the V.A. Fogg from the USCG accident report