Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

19 February 1804 - Gun-brig HMS Cerbere, Lt. Joseph Patey, wrecked on rocks near Berry Head, Torbey

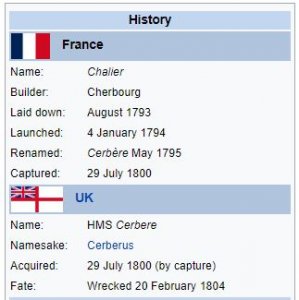

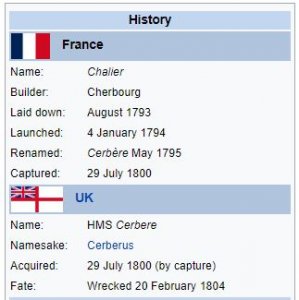

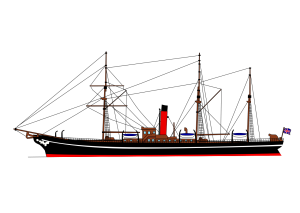

HMS Cerbere was the French naval brig Cerbère, ex-Chalier, which the British captured in 1800. She was wrecked in 1804.

Design

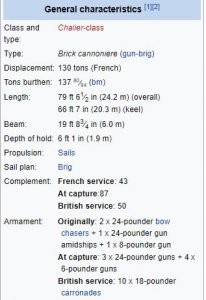

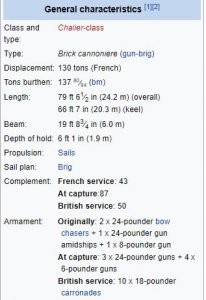

Chalier (Cerbère) was the name vessel of a five-vessel class of brick-cannonnieres (gun-brigs). All were built at Cherbourg to a design by Pierre-Alexandre Forfait. She had no keel and drew only six feet of water.

French service

Between 5 February 1794 and 13 December, Chalier was under the command of enseigne de vaisseau non entretenu Fabien. She was stationed in the bay of Granville. From there she cruised of the coasts of Jersey.

In 1795 Cerbère, by then renamed from Chalier, but still under Fabien's command, escorted convoys between Granville and Cancale.

In 1800 she came under the command of enseigne de vaisseau Menagé.

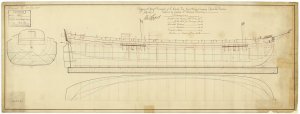

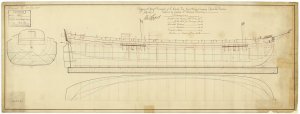

sistership 'Le Crache Feu' (1794) taken by the British by Strachan's off the french Coast 1795

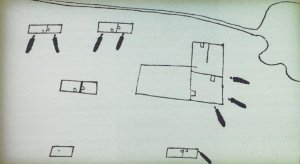

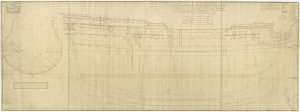

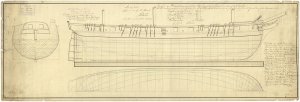

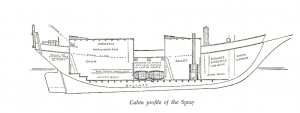

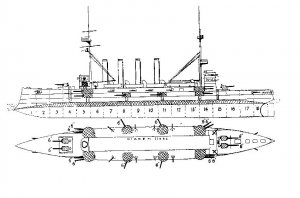

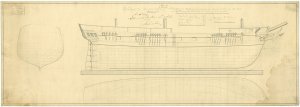

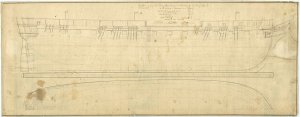

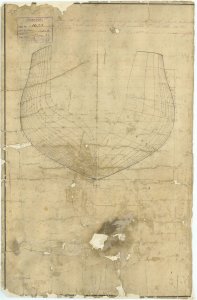

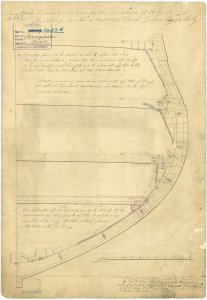

Scale: 1:48. Plan showing the body plan, sheer lines with inboard details, and longitudinal half-breadth for Crache Feu (1795), a captured French 'brick-canonniere' probably as taken off, prior to being fitted as a 3-gun (18 pounder) Gunbrig. Signed by Edward Tippet [Master Shipwright, Portsmouth Dockyard, 1793-1799].

Capture

In September 1799, Lieutenant Jeremiah Coghlan (acting) assumed command HMS Viper. On 1 November Viper recaptured the Diamond.

In July 1800,Coghlan, who had been watching Port-Louis, Morbihan, proposed to Sir Edward Pellew that he, Coghlan, take some boats into the harbour to cut out one of the French vessels there. Pellew acceded to the proposal and gave Coghlan a cutter from Impetueux, Midshipman Silas H. Paddon, and 12 men. Coghlan added in six men from Viper, a boat from Viper, and one from Amethyst. On 29 July the boats went into the port after dark, targeting a brig. During the run-up to the attack the boats from Viper and Amethyst fell behind, but Coghlan in the cutter persisted.

Coghlan's initial attempt at boarding failed and he himself received a pike wound in the thigh. The French repelled a second attempt too. Finally, the British succeeded in boarding, killing and wounding a large number of the French brig's crew, and taking control. The two laggard boats came up and the British then brought the brig out of the harbour and back to the fleet.

The brig was the Cerbère, of three 24-pounder and four 6-pounder guns, with a crew of 87 men, 16 of them soldiers, still under Menagé's command. The attack cost the British one man killed (a seaman from Viper), and eight men wounded, including Coghlan and Paddon. The French lost five men killed and 21 wounded, including all their officers; one of the wounded men died shortly thereafter.

The Royal Navy took Cerbère into service under her existing name. Pellew's fleet waived their right to any prize money as a gesture of admiration for the feat. Pellew also recommended Coglan's promotion to Lieutenant, which followed, though Coghlan had not served the requisite time in grade. Earl St. Vincent personally gave Coghlan a sword worth 100 guineas, in order to "prevent the city, or any body of merchants, from making him a present of the same sort". In 1847 the Admiralty awarded the Naval general Service Medal with clasp, "29 July Boat Service 1800" to the four surviving claimants from the action.

British service and fate

The British brought Cerbere to Plymouth, where she underwent fitting-out from 7 September 1800 to 30 September 1802. At some point she may briefly have been named St Vincent. Still, as Cerbere, she was commissioned in August 1802 under Lieutenant Joseph Patey .

Cerbere was sailing from Guernsey to Plymouth when bad weather forced her to anchor at Torbay. Patey tried to sail again on 14 February but was forced to anchor again. Patey hired a local boat to help warp her out, which took until 20 February when Patey again attempted to sail. As she finally sailed from Brixham Quay a strong wave lifted Cerbere onto rocks at Berry Head that pierced her hull. Spectators on shore saved the crew, all of whom arrived safely on shore.

Cerbere was later raised, but apparently was not taken back into service.

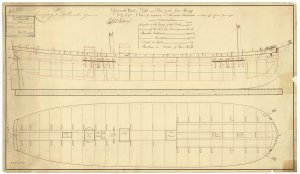

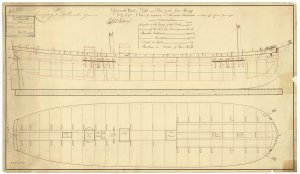

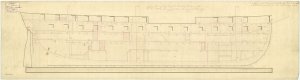

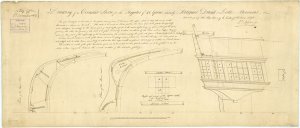

Scale: 1:48. Plan showing the inboard profile, and deck plan for the Crache Feu (captured 1795), a captured French 'brick canonneire', as taken off afloat in June 1795 prior to being fitted as a 3-gun (18 pounders) Gunbrig. Signed by Robert John Nelson [Assistant [?] to Master Shipwright, Portsmouth Dockyard].

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Cerbere_(1800)

https://threedecks.org/index.php?display_type=show_ship&id=16571

https://threedecks.org/index.php?display_type=show_ship&id=3532

https://collections.rmg.co.uk/colle...el-305113;browseBy=vessel;vesselFacetLetter=C

https://threedecks.org/index.php?display_type=show_class&id=420

19 February 1804 - Gun-brig HMS Cerbere, Lt. Joseph Patey, wrecked on rocks near Berry Head, Torbey

HMS Cerbere was the French naval brig Cerbère, ex-Chalier, which the British captured in 1800. She was wrecked in 1804.

Design

Chalier (Cerbère) was the name vessel of a five-vessel class of brick-cannonnieres (gun-brigs). All were built at Cherbourg to a design by Pierre-Alexandre Forfait. She had no keel and drew only six feet of water.

French service

Between 5 February 1794 and 13 December, Chalier was under the command of enseigne de vaisseau non entretenu Fabien. She was stationed in the bay of Granville. From there she cruised of the coasts of Jersey.

In 1795 Cerbère, by then renamed from Chalier, but still under Fabien's command, escorted convoys between Granville and Cancale.

In 1800 she came under the command of enseigne de vaisseau Menagé.

sistership 'Le Crache Feu' (1794) taken by the British by Strachan's off the french Coast 1795

Scale: 1:48. Plan showing the body plan, sheer lines with inboard details, and longitudinal half-breadth for Crache Feu (1795), a captured French 'brick-canonniere' probably as taken off, prior to being fitted as a 3-gun (18 pounder) Gunbrig. Signed by Edward Tippet [Master Shipwright, Portsmouth Dockyard, 1793-1799].

Capture

In September 1799, Lieutenant Jeremiah Coghlan (acting) assumed command HMS Viper. On 1 November Viper recaptured the Diamond.

In July 1800,Coghlan, who had been watching Port-Louis, Morbihan, proposed to Sir Edward Pellew that he, Coghlan, take some boats into the harbour to cut out one of the French vessels there. Pellew acceded to the proposal and gave Coghlan a cutter from Impetueux, Midshipman Silas H. Paddon, and 12 men. Coghlan added in six men from Viper, a boat from Viper, and one from Amethyst. On 29 July the boats went into the port after dark, targeting a brig. During the run-up to the attack the boats from Viper and Amethyst fell behind, but Coghlan in the cutter persisted.

Coghlan's initial attempt at boarding failed and he himself received a pike wound in the thigh. The French repelled a second attempt too. Finally, the British succeeded in boarding, killing and wounding a large number of the French brig's crew, and taking control. The two laggard boats came up and the British then brought the brig out of the harbour and back to the fleet.

The brig was the Cerbère, of three 24-pounder and four 6-pounder guns, with a crew of 87 men, 16 of them soldiers, still under Menagé's command. The attack cost the British one man killed (a seaman from Viper), and eight men wounded, including Coghlan and Paddon. The French lost five men killed and 21 wounded, including all their officers; one of the wounded men died shortly thereafter.

The Royal Navy took Cerbère into service under her existing name. Pellew's fleet waived their right to any prize money as a gesture of admiration for the feat. Pellew also recommended Coglan's promotion to Lieutenant, which followed, though Coghlan had not served the requisite time in grade. Earl St. Vincent personally gave Coghlan a sword worth 100 guineas, in order to "prevent the city, or any body of merchants, from making him a present of the same sort". In 1847 the Admiralty awarded the Naval general Service Medal with clasp, "29 July Boat Service 1800" to the four surviving claimants from the action.

British service and fate

The British brought Cerbere to Plymouth, where she underwent fitting-out from 7 September 1800 to 30 September 1802. At some point she may briefly have been named St Vincent. Still, as Cerbere, she was commissioned in August 1802 under Lieutenant Joseph Patey .

Cerbere was sailing from Guernsey to Plymouth when bad weather forced her to anchor at Torbay. Patey tried to sail again on 14 February but was forced to anchor again. Patey hired a local boat to help warp her out, which took until 20 February when Patey again attempted to sail. As she finally sailed from Brixham Quay a strong wave lifted Cerbere onto rocks at Berry Head that pierced her hull. Spectators on shore saved the crew, all of whom arrived safely on shore.

Cerbere was later raised, but apparently was not taken back into service.

Scale: 1:48. Plan showing the inboard profile, and deck plan for the Crache Feu (captured 1795), a captured French 'brick canonneire', as taken off afloat in June 1795 prior to being fitted as a 3-gun (18 pounders) Gunbrig. Signed by Robert John Nelson [Assistant [?] to Master Shipwright, Portsmouth Dockyard].

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Cerbere_(1800)

https://threedecks.org/index.php?display_type=show_ship&id=16571

https://threedecks.org/index.php?display_type=show_ship&id=3532

https://collections.rmg.co.uk/colle...el-305113;browseBy=vessel;vesselFacetLetter=C

https://threedecks.org/index.php?display_type=show_class&id=420

paper articles were published for months after the incident. Most messages about the disaster were sent out from Barrington Telegraph and relayed to major cities.

paper articles were published for months after the incident. Most messages about the disaster were sent out from Barrington Telegraph and relayed to major cities.

bury

bury