8 August 1745 - John Byng promoted to Rear-Admiral of the Blue - The start of his ending career

Byng is best known for "failing" to relieve a besieged British garrison during the Battle of Minorca at the beginning of the Seven Years' War. Byng had sailed for Minorca at the head of a hastily assembled fleet of vessels, some of which were in poor condition. He fought an inconclusive engagement with a French fleet off the Minorca coast, and then elected to return to Gibraltar to repair his ships. Upon return to Britain, Byng was court-martialled and found guilty of failing to "do his utmost" to prevent Minorca falling to the French. He was sentenced to death and, after pleas for clemency were denied, was shot dead by a firing squad on 14 March 1757.

Remark Uwe:

Remark Uwe: It seems to be, that George Byng was a typical "son", but make your own opinion!

His Father was very experienced and successful

John Byng was born at

Southill Park in the parish of

Southhill in Bedfordshire, England, the fifth son of Rear-Admiral

George Byng, 1st Viscount Torrington (later

Admiral of the Fleet). His father George Byng had supported King

William III in his successful bid to be crowned

King of England in 1689 and had seen his own stature and fortune grow. He was a highly skilled naval commander, had won distinction in a series of battles, and was held in esteem by the monarchs whom he served. In 1721, he was rewarded by

King George I with a

viscountcy, being created

Viscount Torrington.

Commands held

HMS Constant Warwick,

HMS Hope,

HMS Duchess,

HMS Royal Oak,

HMS Britannia,

HMS Nassau

Battles/wars

Glorious Revolution,

Nine Years' War:

Battle of Beachy Head,

War of the Spanish Succession:

Battle of Vigo Bay,

Battle of Málaga,

Battle of Toulon,

War of the Quadruple Alliance:

Battle of Cape Passaro

Career of the son

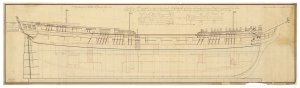

He entered the Royal Navy in March 1718, aged 13, when his father was a well-established admiral at the peak of a uniformly successful career. Early in his career John Byng was assigned to a series of

Mediterranean postings. In 1723, aged 19, he was promoted lieutenant, and at 23, rose to become

captain of

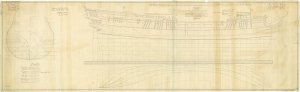

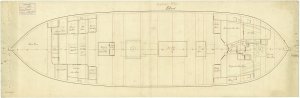

HMS Gibraltar, a 20-gun

sixth rate built in 1711. It was his only command of a ship. His Mediterranean service continued until 1739 and was without much action.

In 1742 he was appointed Commodore-Governor of the

British colony of

Newfoundland. He was promoted to

rear-admiral in 1745, and appointed

Commander-in-Chief, Leith a post he held till 1746. He was promoted to

vice-admiral in 1747. He served as a Member of Parliament for

Rochester from 1751 until his death.

Battle of Minorca

The island of

Minorca had been a British possession since 1708, when it was captured during the

War of the Spanish Succession. On the approach of the

Seven Years' War, it was threatened by a

French naval attack from

Toulon, and was invaded in 1756.

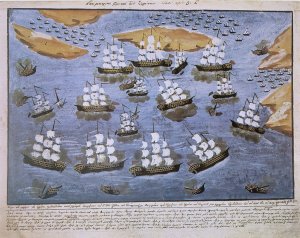

The departure of the French squadron on 10 April 1756 for the attack against Port Mahon. (Nicolas Ozanne, (1728 - 1811)

The departure of the French squadron on 10 April 1756 for the attack against Port Mahon. (Nicolas Ozanne, (1728 - 1811)

Byng was serving in the Channel at the time and was ordered to the Mediterranean to relieve the British garrison of

Fort St Philip, at

Port Mahon. Despite his protests, he was not given enough money or time to prepare the expedition properly. His fleet was delayed in Portsmouth for five days while additional crew were found. By 6 April, the ships had sufficient crew to put to sea, arriving at Gibraltar on 2 May. Byng's

Royal Marines were landed to make room for the soldiers who were to reinforce the garrison, and he feared that, if he met a

French squadron, he would be dangerously undermanned. His correspondence shows that he left prepared for failure, that he did not believe that the garrison could hold out against the French force, and that he was already resolved to come back from Minorca if he found that the task presented any great difficulty. He wrote home to that effect to the Admiralty from

Gibraltar, whose governor refused to provide soldiers to increase the relief force. Byng sailed on 8 May 1756. Before he arrived, the French landed 15,000 troops on the western shore of Minorca, spreading out to occupy the island. On 19 May, Byng was off the east coast of Minorca and endeavoured to open communications with the fort. The French squadron appeared before he could land any soldiers.

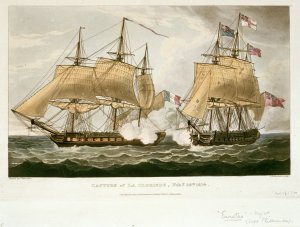

The

Battle of Minorca was fought on the following day.

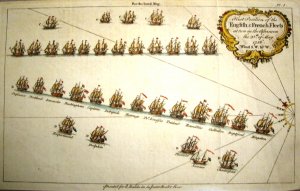

Byng had gained the

weather gage and bore down on the French fleet at an angle, so that his leading ships went into action while the rest were still out of effective firing range, including Byng's flagship. The French badly damaged the leading ships and slipped away. Byng's

flag captain pointed out to him that, by standing out of his line, he could bring the centre of the enemy to closer action, but he declined because

Thomas Mathews had been dismissed for so doing. Neither side lost a ship in the engagement, and casualties were roughly even, with 43 British sailors killed and 168 wounded, against French losses of 38 killed and 175 wounded.

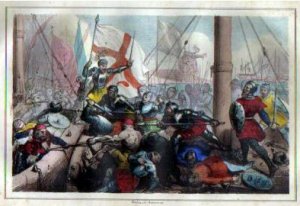

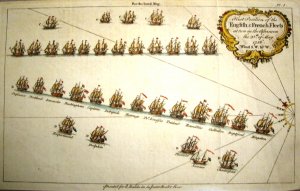

Early copper plate engraving 'First position of the English and French Fleets at two in the afternoon the 20th May 1756. This is the Battle of Minorca during the Seven Years War.

Early copper plate engraving 'First position of the English and French Fleets at two in the afternoon the 20th May 1756. This is the Battle of Minorca during the Seven Years War.

Byng remained near Minorca for four days without establishing communication with the fort or sighting the French. On 24 May, he called a council of his captains at which he suggested that Minorca was effectively lost and that the best course would be to return to Gibraltar to repair the fleet. The council concurred, and the fleet set sail for Gibraltar, arriving on 19 June, where they were reinforced with four more ships of the line and a 50-gun frigate. Repairs were effected to the damaged vessels and additional water and provisions were loaded aboard.

Before his fleet could return to sea, another ship arrived from England with further instructions, relieving Byng of his command and ordering him to return home. On arrival in England he was placed in custody.

Byng had been promoted to full admiral on 1 June, following the action off Minorca but before the Admiralty received Byng's dispatch giving news of the battle. The garrison resisted the

Siege of Fort St Philip until 29 June, when it was forced to capitulate. Under negotiated terms, the garrison was allowed passage back to England, and the fort and island came under French control.

Court-martial

Byng's perceived failure to relieve the garrison at Minorca caused public outrage among fellow officers and the country at large. Byng was brought home to be tried by

court-martial for breach of the

Articles of War, which had recently been revised to mandate capital punishment for officers who did not do their utmost against the enemy, either in battle or pursuit. The revision followed an event in 1745 during the

War of the Austrian Succession, when a young lieutenant named

Baker Phillips was court-martialled and shot after his ship was captured by the French. His captain had done nothing to prepare the vessel for action and was killed almost immediately by a broadside. Taking command, the inexperienced junior officer was forced to surrender the ship when she could no longer be defended. The negligent behaviour of Phillips's captain was noted by the subsequent court martial and a recommendation for mercy was entered, but Phillips' sentence was approved by the

Lords Justices of Appeal. This sentence angered some of parliament, who felt that an officer of higher rank would likely have been spared or else given a light punishment, and that Phillips had been executed because he was a powerless junior officer and thus a useful scapegoat.

The Articles of War were amended to become one law for all: the death penalty for any officer of any rank who did not do his utmost against the enemy in battle or pursuit.

We have lately been told

Of two admirals bold,

We have lately been told

Of two admirals bold,

Who engag'd in a terrible Fight:

They met after Noon,

Which I think was too soon,

As they both ran away before Night.

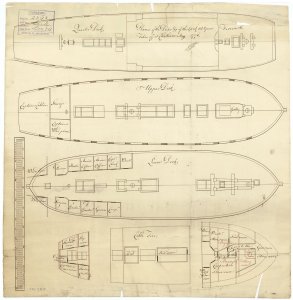

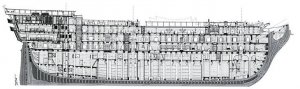

Byng's court martial was convened on 28 December 1756 aboard the elderly 96-gun vessel

HMS St George, which was anchored in Portsmouth Harbour. The presiding officer was Admiral

Thomas Smith, supported by

rear admirals Francis Holburne, Harry Norris and

Thomas Broderick, and a panel of nine

captains. The verdict was delivered four weeks later, on 27 January 1757; in the form of a series of resolutions describing the course of Byng's expedition to Minorca and an interpretation of his actions. The court acquitted Byng of personal cowardice. However its principal findings were that Byng had failed to keep his fleet together while engaging the French; that his flagship had opened fire at too great a distance to have any effect; and that he should have proceeded to the immediate relief of Minorca rather than returning to Gibraltar. As a consequence of these actions, the court held that Byng had

"not done his utmost" to engage or destroy the enemy, thereby breaching the 12th Article of War.

Once the court determined that Byng had "failed to do his utmost", it had no discretion over punishment under the Articles of War. In accordance with those Articles the court condemned Byng to death, but unanimously recommended that the Lords of the Admiralty ask

King George II to exercise his

royal prerogative of mercy.

Clemency denied and execution

First Lord of the Admiralty Richard Grenville-Temple was granted an audience with the King to request clemency, but this was refused in an angry exchange. Four members of the board of the court martial petitioned Parliament, seeking to be relieved from their oath of secrecy to speak on Byng's behalf. The

Commons passed a measure allowing this, but the

Lords rejected the proposal.

Prime Minister

William Pitt the Elder was aware that the Admiralty was at least partly to blame for the loss at Minorca due to the poor manning and repair of the fleet. The

Duke of Newcastle, the politician responsible, had by now joined the Prime Minister in an uneasy

political coalition and this made it difficult for Pitt to contest the court martial verdict as strongly as he would have liked. He did, however, petition the King to commute the death sentence. The appeal was refused; Pitt and

King George II were political opponents, with Pitt having pressed for George to relinquish his hereditary position of

Elector of Hanover as being a conflict of interest with the government's policies in Europe.

The severity of the penalty, combined with suspicion that the Admiralty had sought to protect themselves from public anger over the defeat by throwing all the blame on the admiral, led to a reaction in favour of Byng in both the Navy and the country, which had previously demanded retribution. Pitt, then

Leader of the House of Commons, told the King: "the House of Commons, Sir, is inclined to mercy", to which George responded: "You have taught me to look for the sense of my people elsewhere than in the House of Commons."

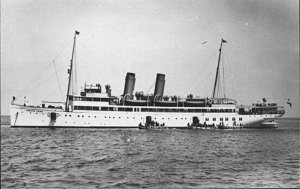

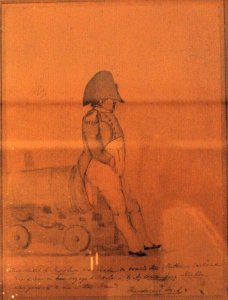

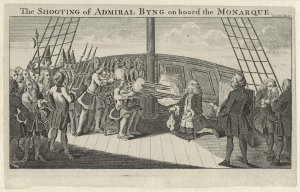

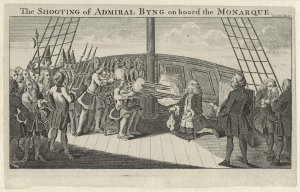

The Shooting of Admiral Byng

The Shooting of Admiral Byng, artist unknown

The King did not exercise his prerogative to grant clemency. Following the court martial and pronouncement of sentence, Admiral Byng had been detained aboard

HMS Monarch in the

Solent and, on 14 March 1757, he was taken to the

quarterdeck for execution in the presence of all hands and men from other ships of the fleet in boats surrounding

Monarch. The admiral knelt on a cushion and signified his readiness by dropping his handkerchief, whereupon a squad of Royal Marines shot him dead

Legacy

Byng's execution was satirised by

Voltaire in his novel

Candide. In Portsmouth, Candide witnesses the execution of an officer by firing squad and is told that

"in this country, it is good to kill an admiral from time to time, in order to encourage the others" (Dans ce pays-ci, il est bon de tuer de temps en temps un amiral pour encourager les autres).

Byng was the last of his rank to be executed in this fashion and, 22 years after the event, the Articles of War were amended to allow "such other punishment as the nature and degree of the offence shall be found to deserve" as an alternative to capital punishment.

In 2007, some of Byng's descendants petitioned the government for a posthumous pardon. The

Ministry of Defence refused. Members of his family continue to seek a pardon, along with a group at Southill in Bedfordshire where the Byng family lived.

Byng's execution has been called "the worst legalistic crime in the nation's annals". But naval historian

N. A. M. Rodger believes it may have influenced the behaviour of later naval officers by helping inculcate:

"a culture of aggressive determination which set British officers apart from their foreign contemporaries, and which in time gave them a steadily mounting psychological ascendancy. More and more in the course of the century, and for long afterwards, British officers encountered opponents who expected to be attacked, and more than half expected to be beaten, so that [the latter] went into action with an invisible disadvantage which no amount of personal courage or numerical strength could entirely make up for."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Byng

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Byng,_1st_Viscount_Torrington

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Minorca_(1756)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Monarch_(1747)