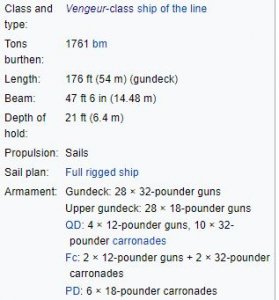

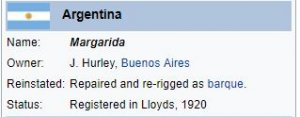

Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

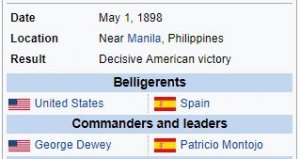

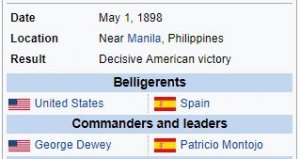

1 May 1898 - Battle of Manila Bay

The American squadron, commanded by Commodore George Dewey, defeats the Spanish squadron under the command of Rear Adm. Montojo at Manila Bay, Philippines.

The

Battle of Manila Bay (

Filipino:

Labanan sa Look ng Maynila Spanish:

Batalla de Bahía de Manila), also known as the

Battle of Cavite, took place on 1 May 1898, during the

Spanish–American War. The American

Asiatic Squadron under

Commodore George Dewey engaged and destroyed the Spanish Pacific Squadron under

Contraalmirante (

Rear admiral)

Patricio Montojo. The

battle took place in

Manila Bay in the

Philippines, and was the first major engagement of the Spanish–American War. The battle was one of the most decisive

naval battles in history and marked the end of the Spanish colonial period in Philippine history.

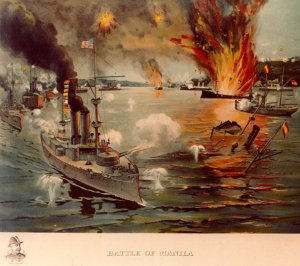

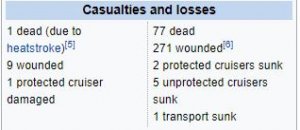

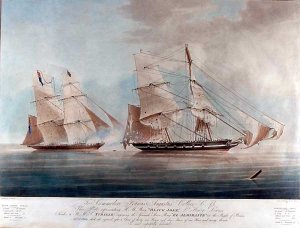

Contemporary colored print, showing

USS Olympia in the left foreground, leading the U.S.

Asiatic Squadron against the

Spanish fleet off

Cavite. A vignette portrait of Rear Admiral

George Dewey is featured in the lower left.

Prelude

Americans living on the

West Coast of the United States feared a Spanish attack at the outbreak of the Spanish–American War. Only a few U.S. Navy warships, led by the

cruiser USS Olympia, stood between them and a powerful Spanish fleet.

Admiral Montojo, a career

Spanish naval officer who had been dispatched rapidly to the Philippines, was equipped with a variety of obsolete vessels. Efforts to strengthen his position amounted to little. The strategy adopted by the Spanish bureaucracy suggested they could not win a war and saw resistance as little more than a face-saving exercise. Administration actions worked against the effort, sending explosives meant for

naval mines to civilian construction companies while the Spanish fleet in

Manila was seriously undermanned by inexperienced sailors who had not received any training for over a year. Reinforcements promised from Madrid resulted in only two poorly-armored scout

cruisers being sent while at the same time the authorities transferred a squadron from the Manila fleet under Admiral

Pascual Cervera to reinforce the

Caribbean. Admiral Montojo had originally wanted to confront the Americans at

Subic Bay, northwest of Manila Bay, but abandoned that idea when he learned the planned mines and coastal defensives were lacking and the cruiser

Castilla started to leak. Montojo compounded his difficulties by placing his ships outside the range of Spanish

coastal artillery (which might have evened the odds) and choosing a relatively shallow anchorage. His intent seems to have been to spare Manila from bombardment and to allow any survivors of his fleet to swim to safety. The harbor was protected by six shore batteries and three

forts whose fire during the battle proved to be ineffective. Only

Fort San Antonio Abad had guns with enough range to reach the American fleet, but Dewey never came within their range during the battle.

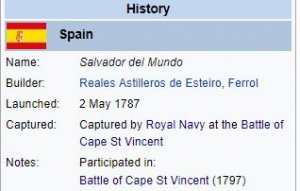

The Spanish squadron consisted of seven ships: the

cruisers Reina Cristina (flagship),

Castilla,

Don Juan de Austria,

Don Antonio de Ulloa,

Isla de Luzon,

Isla de Cuba, and the

gunboat Marques del Duero. The Spanish ships were of inferior quality to the American ships; the

Castilla was unpowered and had to be towed by the transport ship

Manila. On April 25, the squadron left Manila Bay for the port of Subic, intending to mount a defense there. The squadron was relying on a shore battery which was to be installed on Isla Grande. On April 28, before that installation could be completed, a cablegram from the Spanish Consul in Hong Kong arrived with the information that the American squadron had left Hong Kong bound for Subic for the purpose of destroying the Spanish squadron and intending to proceed from there to Manila. The Spanish Council of Commanders, with the exception of the Commander of Subic, felt that no defense of Subic was possible with the state of things, and that the squadron should transfer back to Manila, positioning in shallow water so that the ships could be run aground to save the lives of the crews as a final resort. The squadron departed Subic at 10:30 a.m. on 29 April.

Manila, towing

Castilla, was last to arrive in Manila Bay, at midnight.

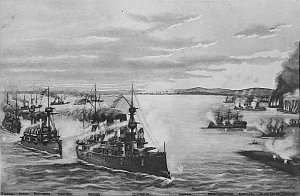

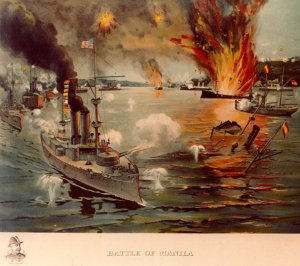

The Battle of Manila Bay, depicted in a lithograph by Butler, Thomas & Company, 1899

Battle

At 7 p.m. on 30 April, Montojo was informed that Dewey's ships had been seen in

Subic Bay that afternoon. As

Manila Bay was considered unnavigable at night by foreigners, Montojo expected an attack the following morning. However,

Oscar F. Williams, the United States Consul in Manila, had provided Dewey with detailed information on the state of the Spanish defenses and the lack of preparedness of the Spanish fleet. Based in part upon this intelligence, Dewey—embarked aboard

USS Olympia—led his squadron into Manila Bay at midnight on 30 April.

Passing the entrance, two Spanish mines exploded but were ineffective as they were well below the draft of any of the ships due to the depth of the water. Inside the bay, ships normally used the north channel between

Corregidor Island and the northern coast, and this was the only channel mined. Dewey instead used the unmined south channel between

El Fraile and

Caballo Islands. The El Fraile battery fired a few rounds but the range was too great. The

McCulloch,

Nanshan and

Zafiro were then detached from the line and took no further part in the fighting. At 5:15 a.m. on 1 May, the squadron was off Manila and the

Cavite battery fired ranging shots. The shore batteries and Spanish fleet then opened fire but all the shells fell short as the fleet was still out of range. At 5:41 with the now famous phrase, "You may fire when ready,

Gridley", the

Olympia's captain was instructed to begin the destruction of the Spanish

flotilla.

The U.S. squadron swung in front of the Spanish ships and forts in

line ahead, firing their

port guns. They then turned and passed back, firing their

starboard guns. This process was repeated five times, each time closing the range from 5,000 yards to 2,000 yards. The Spanish forces had been alerted, and most were ready for action, but they were heavily outgunned. Eight Spanish ships, the land batteries, and the forts returned fire for two and a half hours although the range was too great for the guns on shore. Five other small Spanish ships were not engaged.

Montojo accepted that his cause was hopeless and ordered his ships to ram the enemy if possible. He then slipped the

Cristina's cables and charged. Much of the American fleet's fire was then directed at her and she was shot to pieces. Of the crew of 400, more than 200, including Montojo, were casualties and only two men remained who were able to man her guns. The ship managed to return to shore and Montojo ordered it to be scuttled. The

Castilla, which only had guns on the port side, had her forward cable shot away, causing her to swing about, presenting her weaponless starboard side. The captain then ordered her sunk and abandoned. The

Ulloa was hit by a shell at the waterline that killed her captain and disabled half the crew. The

Luzon had three guns out of action but was otherwise unharmed. The

Duero lost an engine and had only one gun left able to fire.

At 7:45 a.m., after Captain Gridley messaged Dewey that only 15 rounds of 5" ammunition remained per gun, Dewey ordered an immediate withdrawal. To preserve morale, he informed the crews that the halt in the battle was to allow the crews to have breakfast.

[16] According to an observer on the

Olympia, "At least three of his (Spanish) ships had broken into flames but so had one of ours. These fires had all been put out without apparent injury to the ships. Generally speaking, nothing of great importance had occurred to show that we had seriously injured any Spanish vessel." Montojo took the opportunity to now move his remaining ships into

Bacoor Bay where they were ordered to resist for as long as possible.

A captains' conference on the

Olympia revealed little damage and no men killed. It was discovered that the original ammunition message had been garbled—instead of only 15 rounds of ammunition per gun remaining, the message had meant to say only 15 rounds of ammunition per gun had been expended. Reports arrived during the conference that sounds of exploding ammunition had been heard and fires sighted on the

Cristina and

Castilla. At 10:40 a.m. action was resumed but the Spanish offered little resistance, and Montojo issued orders for the remaining ships to be scuttled and the

breechblocks of their guns taken ashore. The

Olympia,

Baltimore and

Boston then fired on the

Sangley Point battery putting it out of action and followed up by sinking the

Ulloa. The

Concord fired on the transport

Mindanao, whose crew immediately abandoned ship. The

Petrel fired on the government offices next to the arsenal and a white flag was raised over the building after which all firing ceased. The Spanish colors were

struck at 12:40 p.m.

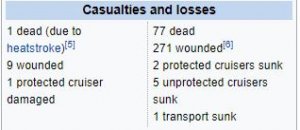

According to American sources, Dewey won the battle with seven men very slightly wounded, a total of nine injured, and only a single fatality among his crew: Francis B. Randall, Chief Engineer on the

McCulloch, from a heart attack. On the other hand, the Spanish naval historian Agustín Ramón Rodríguez González suggests that Dewey suffered heavier losses, though still much lower than those of the Spanish squadron. Rodríguez notes that Spanish officials estimated the American casualties at 13 crewmen killed and more than 30 wounded based on reliable information collected by the Spanish consulate in

Hong Kong.

[6] According to Rodríguez, Dewey may have concealed the deaths and injuries by including the numbers among the 155 men who reportedly deserted during the campaign.

[6]

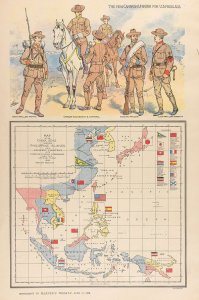

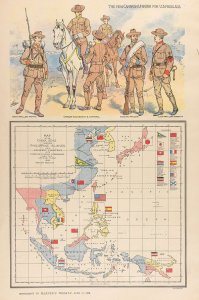

In this "patriotic" map of the China Seas, a large American flag is planted on the spot of the battle of Manila Bay, where on May 1st, Dewey had defeated the Spanish.

Subsequent action

A Spanish attempt to attack Dewey with the naval task force known as

Camara's Flying Relief Column came to naught, and the naval war in the Philippines devolved into a series of

torpedo boat hit-and-run attacks for the rest of the

campaign. While the Spanish scored several hits, there were no American fatalities directly attributable to Spanish gunfire.

On 2 May, Dewey landed a force of

Marines at

Cavite. They completed the destruction of the Spanish fleet and batteries and established a guard for the protection of the Spanish hospitals. The resistance of the forts was weak. The

Olympia turned a few guns on the Cavite arsenal, detonating its

magazine, and ending the fire from the Spanish batteries.

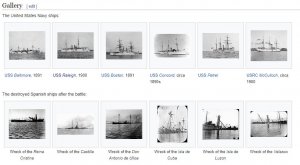

The wreck of

Reina Cristina after the

Battle of Manila Bay in 1898.

Aftermath

In recognition of George Dewey's leadership during the Battle of Manila Bay, a special medal known as the

Dewey Medal was presented to the officers and sailors under Admiral Dewey's command. Dewey was later honored with promotion to the special rank of

Admiral of the Navy; a rank that no one has held before or since in the

United States Navy. Building on his popularity, Dewey briefly

ran for president in 1900, but withdrew and endorsed

William McKinley, the incumbent, who won. The same year Dewey was appointed President of the

General Board of the United States Navy, where he would play a key role in the growth of the U.S. Navy until his death in January 1917.

Dewey Square in Boston is named after Commodore Dewey, as is Dewey Beach, Delaware.

Union Square, San Francisco features a 97 ft (30 m) tall

monument to Admiral George Dewey's victory at the Battle of Manila Bay.

USS

Olympia at the Independence Seaport Museum in 2007

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Manila_Bay

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spanish_cruiser_Velasco

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spanish_cruiser_Don_Juan_de_Austria

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spanish_cruiser_Don_Antonio_de_Ulloa

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spanish_cruiser_Castilla

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Manila_Bay

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spanish_cruiser_Velasco

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spanish_cruiser_Don_Juan_de_Austria

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spanish_cruiser_Don_Antonio_de_Ulloa

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spanish_cruiser_Castilla

en.wikipedia.org

age

age