Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

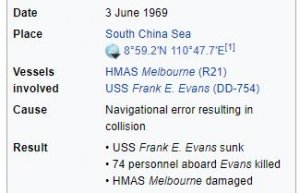

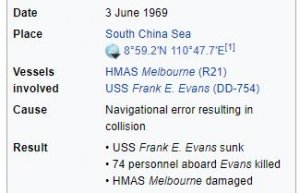

3 June 1969 – Melbourne–Evans collision: off the coast of South Vietnam, the Australian aircraft carrier HMAS Melbourne cuts the U.S. Navy destroyer USS Frank E. Evans in half.

USS Frank E. Evans – On 3 June 1969, while operating as a plane guard for the Australian aircraft carrier HMAS Melbourne in the SEATO training exercise Sea Spirit, the destroyer crossed the bows of the carrier and was rammed and sunk.

Of the 273 aboard Evans, 74 died.

The handling of the inquiry into the collision was seen as detrimental to United States–Australia relations.

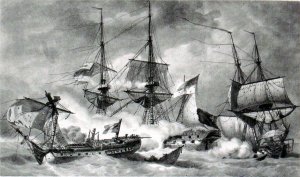

The

Melbourne–Evans collision was a collision between the light aircraft carrier

HMAS Melbourne of the

Royal Australian Navy (RAN) and the destroyer

USS Frank E. Evans of the

United States Navy (USN). On 3 June 1969, the two ships were participating in

SEATO exercise Sea Spirit in the

South China Sea. Around 3:00 am, when ordered to a new escort station,

Evans sailed under

Melbourne's bow, where she was cut in two. Seventy-four of

Evans's crew were killed.

A joint RAN–USN board of inquiry was held to establish the events of the collision and the responsibility of those involved. This inquiry, which was believed by the Australians to be biased against them, found that both ships were at fault for the collision. Four officers (the captains of

Melbourne and

Evans, plus the two junior officers in control of

Evans at the time of the collision) were court-martialled based on the results of the inquiry; while the three USN officers were charged, the RAN officer was cleared of wrongdoing.

The stern section of USS

Frank E. Evans on the morning after the collision. USS

Everett F. Larson(right) is moving in to salvage the remains of the abandoned destroyer.

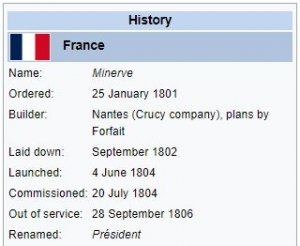

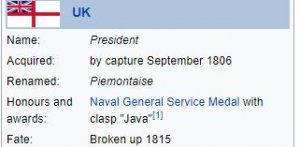

Ships

Main articles:

HMAS Melbourne (R21) and

USS Frank E. Evans (DD-754)

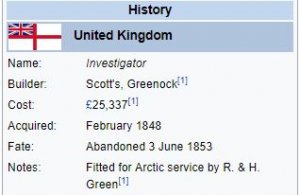

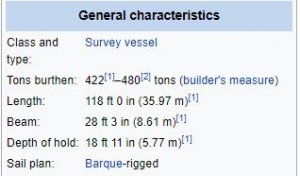

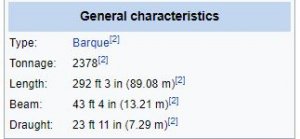

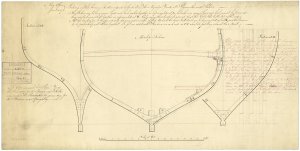

HMAS

Melbourne was the lead ship of the

Majestic class of aircraft carriers. She was laid down for the

Royal Navy on 15 April 1943, but construction was stopped at the end of World War II. She was sold to the Royal Australian Navy in 1948, along with

sister shipHMAS Sydney, but was heavily upgraded while construction was completed and did not enter service until the end of 1955. In 1964,

Melbourne was

involved in a collision with the Australian destroyer

HMAS Voyager, sinking the smaller ship and killing 81 of her crew and one civilian dockyard worker.

USS

Frank E. Evans was an

Allen M. Sumner-class destroyer. She was laid down on 21 April 1944, and commissioned into the United States Navy on 3 February 1945. She served in World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War, and earned 11

battle stars.

Lead up

Melbourne's commanding officer during the SEATO exercise was Captain John Phillip Stevenson. Rear Admiral

John Crabb, the Flag Officer Commanding Australian Fleet, was also embarked on the carrier. During Sea Spirit,

Melbourne was assigned five escorts: the US destroyers

Everett F. Larson,

Frank E. Evans and

James E. Kyes, and the frigates

HMNZS Blackpool and

HMS Cleopatra. Stevenson held a dinner for the five escort captains at the start of the exercise, during which he recounted the events of the

Melbourne–Voyager collision, emphasised the need for caution when operating near the carrier, and provided written instructions on how to avoid such a situation developing again. Additionally, during the lead-up to the exercise, Admiral Crabb had strongly warned that all repositioning manoeuvres performed by the escorts had to commence with a turn away from

Melbourne.

Despite these warnings, a near-miss occurred in the early hours of 31 May when

Larson turned toward the carrier after being ordered to the

plane guard station. Subsequent action narrowly prevented a collision. The escorts were again warned about the dangers of operating near the carrier and informed of Stevenson's expectations, while the minimum distance between carrier and escorts was increased from 2,000 to 3,000 yd (1,800 to 2,700 m).

Collision

On the night of 2–3 June,

Melbourne and her escorts were involved in anti-submarine training exercises. In preparation for launching a

Grumman S-2 Tracker aircraft, Stevenson ordered

Evans to the

plane guard station, reminded the destroyer of

Melbourne's course, and instructed the carrier's navigational lights to be brought to full brilliance. This was the fourth time that

Evans had been asked to assume this station that night, and the previous three manoeuvres had been without incident.

Evans was positioned on

Melbourne's port bow, but began the manoeuvre by turning starboard, towards the carrier. A radio message was sent from

Melbourne to

Evans's bridge and

Combat Information Centre, warning the destroyer that she was on a collision course, which

Evans acknowledged. Seeing the destroyer take no action and on a course to place herself under

Melbourne's bow, Stevenson ordered the carrier hard to port, signalling the turn by both radio and siren blasts. At approximately the same time,

Evans turned hard to starboard to avoid the approaching carrier. It is uncertain which ship began to manoeuvre first, but each ship's bridge crew claimed that they were informed of the other ship's turn after they commenced their own. After having narrowly passed in front of

Melbourne, the turns quickly placed

Evans back in the carrier's path.

Melbourne hit

Evans amidships at 3:15 am, cutting the destroyer in two.

The paths taken by HMAS

Melbourne and USS

Frank E. Evans in the minutes leading up to the collision

Melbourne stopped immediately after the collision and deployed her boats, liferafts and lifebuoys, before carefully manoeuvring alongside the stern section of

Evans. Sailors from both ships used mooring lines to lash the two ships together, allowing

Melbourne to evacuate the survivors in that section. The bow section sank quickly; the majority of those killed were believed to have been trapped within. Members of

Melbourne's crew dived into the water to rescue overboard survivors close to the carrier, while the carrier's boats and helicopters collected those farther out. Clothing, blankets and beer were provided to survivors from the carrier's stores, some RAN sailors offered their own uniforms, and the ship's band was instructed to set up on the flight deck to entertain and distract the USN personnel. All of the survivors were located within 12 minutes of the collision and rescued before half an hour had passed, although the search continued for 15 more hours.

Seventy-four of the 273 crew on

Evans were killed. It was later learned that

Evans's commanding officer—Commander Albert S. McLemore—was asleep in his quarters at the time of the incident, and charge of the vessel was held by Lieutenants Ronald Ramsey and James Hopson; the former had failed the qualification exam to

stand watch, while the latter was at sea for the first time.

Post-collision events

Following the evacuation of

Evans's stern, the section was cast off while the carrier moved away to avoid damage, but against expectation, it failed to sink. The stern was recovered and towed by fleet tug

USS Tawasa to

Subic Bay, arriving there on 9 June. After being stripped for parts, the hulk was decommissioned on 1 July, and was later sunk when used for target practice.

Melbourne travelled to Singapore, arriving on 6 June, where she received temporary repairs to her bow. The carrier departed on 27 June, and arrived in Sydney on 9 July, where she remained until November docked at

Cockatoo Island Dockyard for repairs and installation of the new bow.

817 Squadron RAN—which was responsible for the

Westland Wessex helicopters embarked on

Melbourne at the time of the collision—later received a USN Meritorious Unit Commendation for its rescue efforts. Five other decorations were presented to Australian personnel in relation to the rescue of

Evans's crew: one

George Medal, one

Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE), one

Air Force Cross, and two

British Empire Medals.

[20] Fifteen additional commendations for gallantry were awarded by the Australian Naval Board.

Joint board of inquiry

A joint RAN–USN board of inquiry was established to investigate the incident, following the passing of special regulations allowing the presence of Australian personnel at a U.S. inquiry. The board was in session for over 100 hours between 9 June and 14 July, with 79 witnesses interviewed: 48 USN, 28 RAN, and three from other navies.

The board was made up of six officers. The RAN representatives were Rear Admiral

David Stevenson (no relation to

Melbourne's Captain Stevenson), Captain Ken Shards, and Captain John Davidson. The USN officers were Captains S. L. Rusk and C. B. Anderson. Presiding over the board was USN Rear Admiral

Jerome King: considered to be an unwise posting as he was the commanding officer of both the forces involved in the SEATO exercise and the fleet unit

Evans normally belonged to, and was seen during the inquiry to be biased against Captain Stevenson and other RAN personnel. King's attitude, performance, and conflict of interest were criticised by the Australians present at the inquiry and the press, and his handling of the inquiry was seen as detrimental to

relations between the two countries.

Despite admissions by members of the USN, given privately to personnel in other navies, that the incident was entirely the fault of

Evans, significant attempts were made to reduce the U.S. destroyer's culpability and place at least partial blame for the incident on

Melbourne. At the beginning of the inquiry, King banned one of the RAN legal advisers from attending, even as an observer. He regularly intervened for American witnesses, but failed to do so on similar matters for the Australians. Testimony on the collision and the subsequent rescue operation was to be given separately, and although requests by American personnel to give both sets of testimony at the same time in order to return to their duties were regularly granted, the same request made by Stevenson was denied by King. Testimony of members of the RAN had to be given under oath, and witnesses faced intense questioning from King, despite the same conditions not applying to USN personnel. There was also a heavy focus on the adequacy of

Melbourne's navigational lighting. Mentions of the near miss with

Larson were interrupted with the instruction that those details could be recounted at a later time, but the matter was never raised by the board.

The unanimous decision of the board was that although

Evans was partially at fault for the collision,

Melbourne had contributed by not taking evasive action sooner, even though doing this would have been a direct contravention of international sea regulations, which stated that in the lead-up to a collision, the larger ship was required to maintain course and speed. The report was inconsistent in several areas with the evidence given at the inquiry, including the falsity that

Melbourne's navigational lights took significant time to come to full brilliance. Several facts were also edited out of the transcripts of the inquiry.

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org