Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

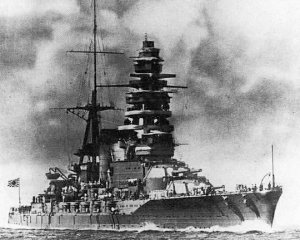

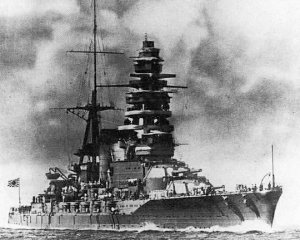

8 June 1943 - Mutsu – On 8 June 1943, while at Hashirajima fleet anchorage, the Japanese battleship suffered an internal explosion and sank.

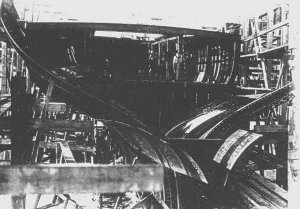

At the time 113 flying cadets and 40 instructors from the Tsuchiura Naval Air Group were aboard for familiarization. The magazine of her No. 3 turret exploded destroying the adjacent structure of the ship and cutting her in half. A massive influx of water into the machinery spaces caused the 150-meter (490 ft) forward section of the ship to capsize starboard and sink almost immediately. The 45-meter (148 ft) stern section upended and floated until about 02:00 hrs on 9 June before sinking a few hundred feet south of the main wreck. Of 1,474 crew and visitors aboard, 1,121 were killed in the explosion.

Mutsu was the second and last Nagato-class dreadnought battleship built for the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) at the end of World War I. It was named after the province, In 1923 she carried supplies for the survivors of the Great Kantō earthquake. The ship was modernized in 1934–1936 with improvements to her armour and machinery, and a rebuilt superstructure in the pagoda mast style.

Other than participating in the Battle of Midway and the Battle of the Eastern Solomons in 1942, where she did not see any significant combat, Mutsu spent most of the first year of the Pacific War in training. She returned to Japan in early 1943. That June, one of her aft magazines detonated while she was at anchor, sinking the ship with the loss of 1,121 crew and visitors. The IJN investigation into the cause of her loss concluded that it was the work of a disgruntled crew member. The navy dispersed the survivors in an attempt to conceal the sinking in the interest of morale in Japan. Much of the wreck was scrapped after the war, but some artefacts and relics are on display in Japan, and a small portion of the ship remains where it was sunk.

Loss

On 8 June 1943, Mutsu was moored in the Hashirajima fleet anchorage, with 113 flying cadets and 40 instructors from the Tsuchiura Naval Air Group aboard for familiarisation. At 12:13 the magazine of her No. 3 turret exploded, destroying the adjacent structure of the ship and cutting her in half. A massive influx of water into the machinery spaces caused the 150-metre (490 ft) forward section of the ship to capsize to starboard and sink almost immediately. The 45-metre (148 ft) stern section upended and remained floating until about 02:00 hours on 9 June before sinking, coming to rest a few hundred feet south of the main wreck at coordinates 33°58′N 132°24′ECoordinates:

33°58′N 132°24′E.

33°58′N 132°24′E.

The nearby Fusō immediately launched two boats which, together with the destroyers Tamanami and Wakatsuki and the cruisers Tatsuta and Mogami, rescued 353 survivors from the 1,474 crew members and visitors aboard Mutsu; 1,121 men were killed in the explosion. Only 13 of the visiting aviators were among the survivors.

After the explosion, as the rescue operations commenced, the fleet was alerted and the area was searched for Allied submarines, but no traces were found. To avert the potential damage to morale from the loss of a battleship so soon after the string of recent setbacks in the war effort, Mutsu's destruction was declared a state secret. Mass cremations of recovered bodies began almost immediately after the sinking. Captain Teruhiko Miyoshi's body was recovered by divers on 17 June, but his wife was not officially notified until 6 January 1944. Both he and his second in command, Captain Koro Oono, were posthumously promoted to rear admiral, as was normal practice. To further prevent rumours from spreading, healthy and recovered survivors were reassigned to various garrisons in the Pacific Ocean. Some of the survivors were sent to Truk in the Caroline Islands and assigned to the 41st Guard Force. Another 150 were sent to Saipan in the Mariana Islands, where most were killed in 1944 during the battle for the island.

At the time of the explosion, Mutsu's magazine contained some 16-inch Type 3 "Sanshikidan" incendiary shrapnel anti-aircraft shells, which had caused a fire at the Sagami arsenal several years earlier due to improper storage. Because they might have been the cause of the explosion, the minister of the navy, Admiral Shimada Shigetaro, immediately ordered the removal of Type 3 shells from all IJN ships carrying them, until the conclusion of the investigation into the loss.

Investigation into the loss

A commission led by Admiral Kōichi Shiozawa was convened three days after the sinking to investigate the loss. The commission considered several possible causes:

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

8 June 1943 - Mutsu – On 8 June 1943, while at Hashirajima fleet anchorage, the Japanese battleship suffered an internal explosion and sank.

At the time 113 flying cadets and 40 instructors from the Tsuchiura Naval Air Group were aboard for familiarization. The magazine of her No. 3 turret exploded destroying the adjacent structure of the ship and cutting her in half. A massive influx of water into the machinery spaces caused the 150-meter (490 ft) forward section of the ship to capsize starboard and sink almost immediately. The 45-meter (148 ft) stern section upended and floated until about 02:00 hrs on 9 June before sinking a few hundred feet south of the main wreck. Of 1,474 crew and visitors aboard, 1,121 were killed in the explosion.

Mutsu was the second and last Nagato-class dreadnought battleship built for the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) at the end of World War I. It was named after the province, In 1923 she carried supplies for the survivors of the Great Kantō earthquake. The ship was modernized in 1934–1936 with improvements to her armour and machinery, and a rebuilt superstructure in the pagoda mast style.

Other than participating in the Battle of Midway and the Battle of the Eastern Solomons in 1942, where she did not see any significant combat, Mutsu spent most of the first year of the Pacific War in training. She returned to Japan in early 1943. That June, one of her aft magazines detonated while she was at anchor, sinking the ship with the loss of 1,121 crew and visitors. The IJN investigation into the cause of her loss concluded that it was the work of a disgruntled crew member. The navy dispersed the survivors in an attempt to conceal the sinking in the interest of morale in Japan. Much of the wreck was scrapped after the war, but some artefacts and relics are on display in Japan, and a small portion of the ship remains where it was sunk.

Loss

On 8 June 1943, Mutsu was moored in the Hashirajima fleet anchorage, with 113 flying cadets and 40 instructors from the Tsuchiura Naval Air Group aboard for familiarisation. At 12:13 the magazine of her No. 3 turret exploded, destroying the adjacent structure of the ship and cutting her in half. A massive influx of water into the machinery spaces caused the 150-metre (490 ft) forward section of the ship to capsize to starboard and sink almost immediately. The 45-metre (148 ft) stern section upended and remained floating until about 02:00 hours on 9 June before sinking, coming to rest a few hundred feet south of the main wreck at coordinates 33°58′N 132°24′ECoordinates:

The nearby Fusō immediately launched two boats which, together with the destroyers Tamanami and Wakatsuki and the cruisers Tatsuta and Mogami, rescued 353 survivors from the 1,474 crew members and visitors aboard Mutsu; 1,121 men were killed in the explosion. Only 13 of the visiting aviators were among the survivors.

After the explosion, as the rescue operations commenced, the fleet was alerted and the area was searched for Allied submarines, but no traces were found. To avert the potential damage to morale from the loss of a battleship so soon after the string of recent setbacks in the war effort, Mutsu's destruction was declared a state secret. Mass cremations of recovered bodies began almost immediately after the sinking. Captain Teruhiko Miyoshi's body was recovered by divers on 17 June, but his wife was not officially notified until 6 January 1944. Both he and his second in command, Captain Koro Oono, were posthumously promoted to rear admiral, as was normal practice. To further prevent rumours from spreading, healthy and recovered survivors were reassigned to various garrisons in the Pacific Ocean. Some of the survivors were sent to Truk in the Caroline Islands and assigned to the 41st Guard Force. Another 150 were sent to Saipan in the Mariana Islands, where most were killed in 1944 during the battle for the island.

At the time of the explosion, Mutsu's magazine contained some 16-inch Type 3 "Sanshikidan" incendiary shrapnel anti-aircraft shells, which had caused a fire at the Sagami arsenal several years earlier due to improper storage. Because they might have been the cause of the explosion, the minister of the navy, Admiral Shimada Shigetaro, immediately ordered the removal of Type 3 shells from all IJN ships carrying them, until the conclusion of the investigation into the loss.

Investigation into the loss

A commission led by Admiral Kōichi Shiozawa was convened three days after the sinking to investigate the loss. The commission considered several possible causes:

- Sabotage by enemy secret agents. Given the heavy security at the anchorage and lack of claims of responsibility by the Allies, this could be discounted.

- Sabotage by a disgruntled crewman. While no individual was named in the commission's final report, its conclusion was that the cause of the explosion was most likely a crewman in No. 3 turret who had recently been accused of theft and was believed to be suicidal.

- A midget or fleet submarine attack. Extensive searches immediately following the sinking had failed to detect any enemy submarine, and the Allies had made no attempt at claiming the enormous propaganda value of sinking a capital ship in her home anchorage; consequently, this possibility was quickly discounted. Eyewitnesses also spoke of a reddish-brown fireball, which indicated a magazine explosion; this was confirmed during exploration of the wreck by divers.

- Accidental explosion within a magazine. While the Mutsu carried many projectiles, immediate suspicion focused on the Type 3 anti-aircraft shell as it was believed to have caused a fire before the war at the Sagami arsenal. Known as "sanshiki-dan", these were fired by the main armament and contained 900 to 1,200 25 mm diameter steel tubes (depending upon sources), each containing an incendiary charge. Tests were conducted at Kamegakubi Naval Proving Ground on several shells salvaged from No. 3 turret and on shells from the previous and succeeding manufacturing batches. Using a specially built model of the Mutsu's No. 3 turret, the experiments were unable to induce the shells to explode under normal conditions.

A number of observers noted smoke coming from the vicinity of No. 3 turret and the aircraft area just forward of it, just before the explosion. Compared with other nations' warships in wartime service, Japanese battleships contained a large amount of flammable materials including wooden decking, furniture, and insulation, as well as cotton and wool bedding. Although she had been modernized in the 1930s, some of the Mutsu's original electrical wiring may have remained in use. While fire in the secure magazines was a very remote possibility, a fire in an area adjacent to the No. 3 magazine could have raised the temperature to a level sufficient to ignite the highly sensitive black-powder primers stored in the magazine and thus cause the explosion.

Japanese battleship Mutsu - Wikipedia

Last edited by a moderator:

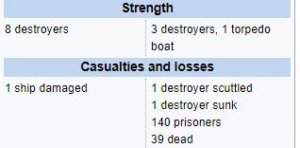

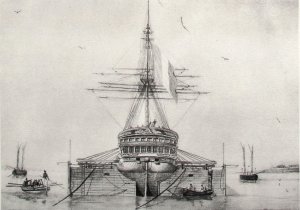

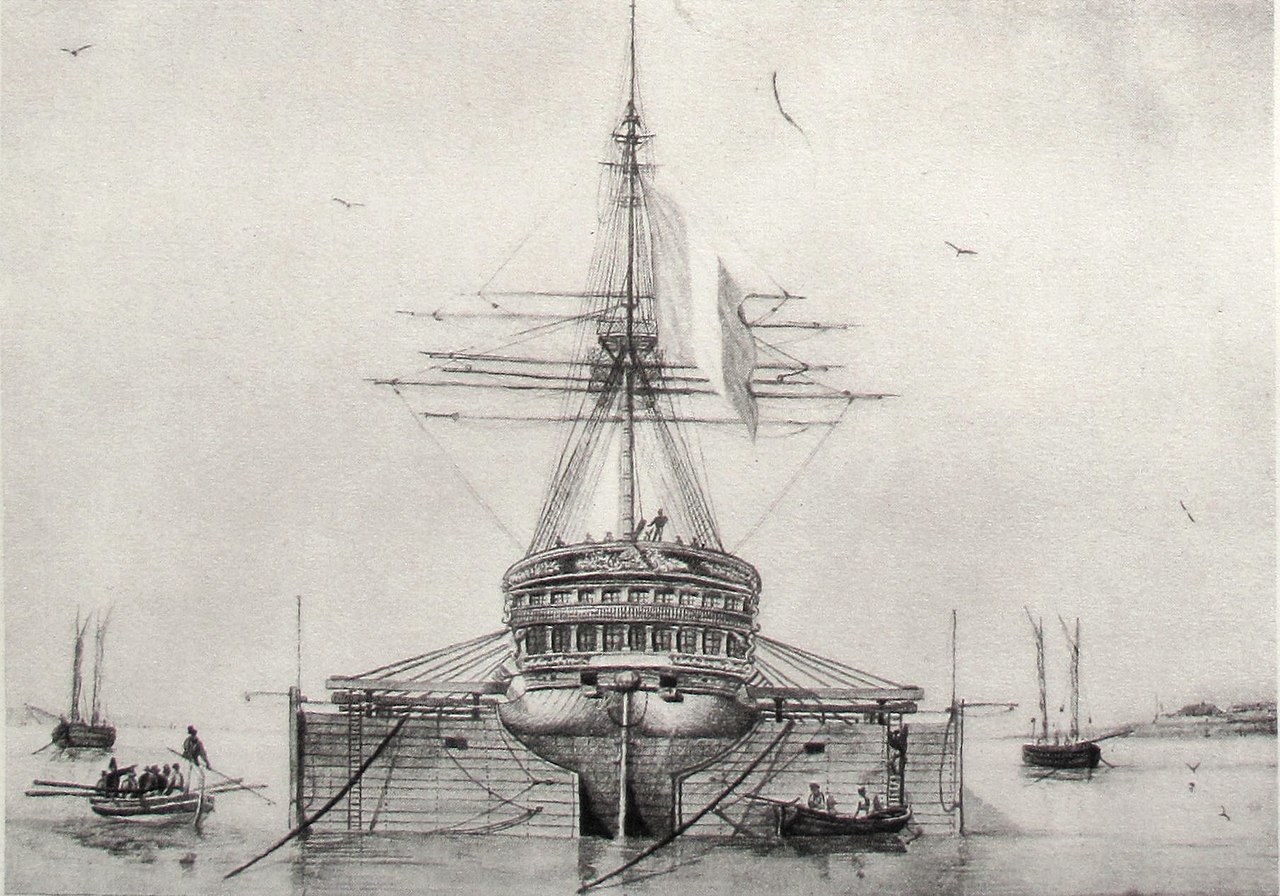

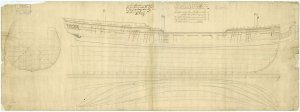

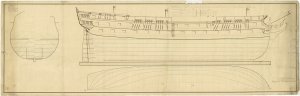

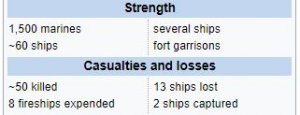

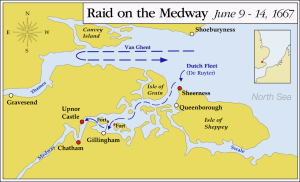

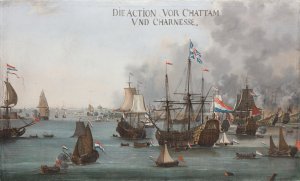

brought us that, the Dutch are come up as high as the Nore; and more pressing orders for fireships." The next day a growing sense of panic becomes apparent: "Up, and more letters still from Sir W. Coventry about more fire-ships, and so Sir W. Batten and I to the office, where Bruncker come to us, who is just now going to Chatham upon a desire of Commissioner Pett's, who is in a very fearful stink for fear of the Dutch, and desires help for God and the King and kingdom's sake. So Bruncker goes down, and Sir J. Minnes also, from Gravesend. This morning Pett writes us word that Sheernesse is lost last night, after two or three hours' dispute. The enemy hath possessed himself of that place; which is very sad, and puts us into great fears of Chatham." In the morning of the 12th he is reassured by the measures taken by Monck: "(...) met Sir W. Coventry's boy; and there in his letter find that the Dutch had made no motion since their taking Sheernesse; and the Duke of Albemarle writes that all is safe as to the great ships against any assault, the boom and chaine being so fortified; which put my heart into great joy." Soon, however, this confidence is shattered: "(...)his clerk, Powell, do tell me that ill newes is come to Court of the Dutch breaking the Chaine at Chatham; which struck me to the heart. And to

brought us that, the Dutch are come up as high as the Nore; and more pressing orders for fireships." The next day a growing sense of panic becomes apparent: "Up, and more letters still from Sir W. Coventry about more fire-ships, and so Sir W. Batten and I to the office, where Bruncker come to us, who is just now going to Chatham upon a desire of Commissioner Pett's, who is in a very fearful stink for fear of the Dutch, and desires help for God and the King and kingdom's sake. So Bruncker goes down, and Sir J. Minnes also, from Gravesend. This morning Pett writes us word that Sheernesse is lost last night, after two or three hours' dispute. The enemy hath possessed himself of that place; which is very sad, and puts us into great fears of Chatham." In the morning of the 12th he is reassured by the measures taken by Monck: "(...) met Sir W. Coventry's boy; and there in his letter find that the Dutch had made no motion since their taking Sheernesse; and the Duke of Albemarle writes that all is safe as to the great ships against any assault, the boom and chaine being so fortified; which put my heart into great joy." Soon, however, this confidence is shattered: "(...)his clerk, Powell, do tell me that ill newes is come to Court of the Dutch breaking the Chaine at Chatham; which struck me to the heart. And to