Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

2 October 1942 – World War II: Ocean Liner RMS Queen Mary accidentally rams and sinks her own escort ship, HMS Curacoa, off the coast of Ireland, killing 337 crewmen aboard the Curacoa.

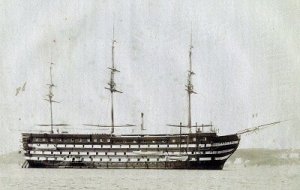

HMS Curacoa was a C-class light cruiser built for the Royal Navy during the First World War. She was one of the five ships of the Ceres sub-class and spent much of her career as a flagship. The ship was assigned to the Harwich Force during the war, but saw little action as she was completed less than a year before the war ended. Briefly assigned to the Atlantic Fleet in early 1919, Curacoa was deployed to the Baltic in May to support anti-Bolshevik forces during the British campaign in the Baltic during the Russian Civil War. Shortly thereafter the ship struck a naval mine and had to return home for repairs.

After spending the rest of 1919 and 1920 in reserve, she later rejoined the Atlantic Fleet and remained there until 1928, aside from a temporary transfer to the Mediterranean Fleet in 1922–1923 to support British interests in Turkey during the Chanak Crisis. Curacoa was then transferred to the Mediterranean Fleet in 1929.

In 1933, she became a training ship and in July 1939, two months before the commencement of the Second World War, Curacoa was converted into an anti-aircraft cruiser. She returned to service in January 1940 and, while providing escort in the Norwegian Campaign that April, was damaged by German aircraft. After repairs were completed that year, she escorted convoys in and around the British Isles for two years. In late 1942, during escort duty, she was accidentally sliced in half and sunk by the ocean liner RMS Queen Mary, with the loss of 337 men.

Collision

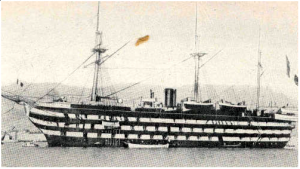

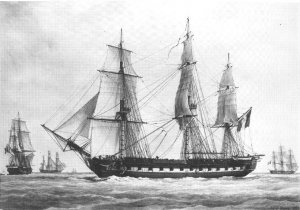

RMS Queen Mary, 20 June 1945, in New York Harborcarrying US troops from Europe

On the morning of 2 October 1942, Curacoa rendezvoused north of Ireland with the ocean liner Queen Mary, which was carrying approximately 10,000 American troops of the 29th Infantry Division. The liner was steaming an evasive "Zig-Zag Pattern No. 8" course at a speed of 28.5 knots (52.8 km/h; 32.8 mph), an overall rate of advance of 26.5 knots (49.1 km/h; 30.5 mph), to evade submarine attacks. The elderly cruiser remained on a straight course at a top speed of 25 knots (46 km/h; 29 mph) and would eventually be overtaken by the liner.

Each captain had different interpretations of The Rule of the Road believing his ship had the right of way. Captain John Wilfred Boutwood of the Curacoa kept to the liner's mean course to maximize his ability to defend the liner from enemy aircraft, while Commodore Sir Cyril Gordon Illingworth of Queen Mary continued their zig-zag pattern expecting the escort cruiser to give way.

Acting under orders not to stop due to the risk of U-boat attacks, Queen Mary steamed onwards with a damaged bow. She radioed the other destroyers of her escort, about 7 nautical miles (13 km; 8.1 mi) away, and reported the collision. Hours later, the convoy's lead escort, consisting of Bramham and one other ship,[40] returned to rescue approximately 101 survivors, including Boutwood. Lost with Curacoa were 337 officers and men of her crew, according to the naval casualty file released by The National Archives in June 2013. Most of the lost men are commemorated on the Chatham Naval Memorial and the rest on the Portsmouth Naval Memorial. Those who died after rescue, or whose bodies were recovered, were buried in Chatham and in Arisaig Cemetery in Invernesshire. Under the Protection of Military Remains Act 1986, Curacoa's wrecksite is designated a "protected place".

Those who witnessed the collision were sworn to secrecy due to national security concerns. The loss was not publicly reported until after the war ended, although the Admiralty filed a writ against Queen Mary's owners, Cunard White Star Line, on 22 September 1943 in the Admiralty Court of the High Court of Justice. Little happened until 1945, when the case went to trial in June; it was adjourned to November and then to December 1946. Mr. Justice Pilcher exonerated the Queen Mary's crew and her owners from blame on 21 January 1947 and laid all fault on Curacoa's officers. The Admiralty appealed his ruling and the Court of Appeal modified the ruling, assigning two-thirds of the blame to the Admiralty and one third to Cunard White Star. The latter appealed to the House of Lords, but they upheld the decision.

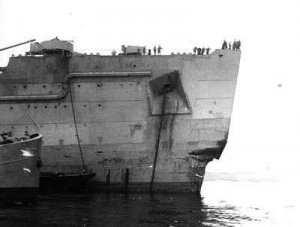

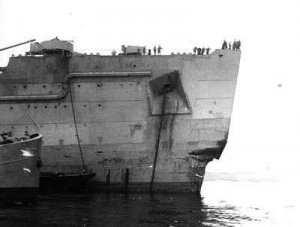

The damaged bow of Queen Mary

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Curacoa_(D41)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/RMS_Queen_Mary

http://linerlogbook.blogspot.com/2014/09/needn-worryhe-will-keep-out-of-your-way.html

2 October 1942 – World War II: Ocean Liner RMS Queen Mary accidentally rams and sinks her own escort ship, HMS Curacoa, off the coast of Ireland, killing 337 crewmen aboard the Curacoa.

HMS Curacoa was a C-class light cruiser built for the Royal Navy during the First World War. She was one of the five ships of the Ceres sub-class and spent much of her career as a flagship. The ship was assigned to the Harwich Force during the war, but saw little action as she was completed less than a year before the war ended. Briefly assigned to the Atlantic Fleet in early 1919, Curacoa was deployed to the Baltic in May to support anti-Bolshevik forces during the British campaign in the Baltic during the Russian Civil War. Shortly thereafter the ship struck a naval mine and had to return home for repairs.

After spending the rest of 1919 and 1920 in reserve, she later rejoined the Atlantic Fleet and remained there until 1928, aside from a temporary transfer to the Mediterranean Fleet in 1922–1923 to support British interests in Turkey during the Chanak Crisis. Curacoa was then transferred to the Mediterranean Fleet in 1929.

In 1933, she became a training ship and in July 1939, two months before the commencement of the Second World War, Curacoa was converted into an anti-aircraft cruiser. She returned to service in January 1940 and, while providing escort in the Norwegian Campaign that April, was damaged by German aircraft. After repairs were completed that year, she escorted convoys in and around the British Isles for two years. In late 1942, during escort duty, she was accidentally sliced in half and sunk by the ocean liner RMS Queen Mary, with the loss of 337 men.

Collision

RMS Queen Mary, 20 June 1945, in New York Harborcarrying US troops from Europe

On the morning of 2 October 1942, Curacoa rendezvoused north of Ireland with the ocean liner Queen Mary, which was carrying approximately 10,000 American troops of the 29th Infantry Division. The liner was steaming an evasive "Zig-Zag Pattern No. 8" course at a speed of 28.5 knots (52.8 km/h; 32.8 mph), an overall rate of advance of 26.5 knots (49.1 km/h; 30.5 mph), to evade submarine attacks. The elderly cruiser remained on a straight course at a top speed of 25 knots (46 km/h; 29 mph) and would eventually be overtaken by the liner.

Each captain had different interpretations of The Rule of the Road believing his ship had the right of way. Captain John Wilfred Boutwood of the Curacoa kept to the liner's mean course to maximize his ability to defend the liner from enemy aircraft, while Commodore Sir Cyril Gordon Illingworth of Queen Mary continued their zig-zag pattern expecting the escort cruiser to give way.

We could see our escort zig-zagging in front of us - it was common for the ships and cruisers to zig-zag to confuse the U-boats. In this particular case however the escort was very, very close to us.

I said to my mate "You know she's zig-zigging all over the place in front of us, I'm sure we're going to hit her."

And sure enough, the Queen Mary sliced the cruiser in two like a piece of butter, straight through the six-inch armoured plating.

— Alfred Johnson, eye witness, BBC: "HMS Curacao Tragedy"

At 13:32, during the zig-zag, it became apparent that Queen Mary would come too close to the cruiser and the liner's officer of the watch interrupted the turn to avoid Curacoa. Upon hearing this command, Illingworth told his officer to: "Carry on with the zig-zag. These chaps are used to escorting; they will keep out of your way and won't interfere with you." At 14:04, Queen Mary started the starboard turn from a position slightly behind the cruiser and at a distance of two cables (about 400 yards (366 m)). Boutwood perceived the danger, but the distance was too close for either of the hard turns ordered for each ship to make any difference at the speeds that they were travelling. Queen Mary struck Curacoa amidships at full speed, cutting the cruiser in half. The aft end sank almost immediately, but the rest of the ship stayed on the surface a few minutes longer.I said to my mate "You know she's zig-zigging all over the place in front of us, I'm sure we're going to hit her."

And sure enough, the Queen Mary sliced the cruiser in two like a piece of butter, straight through the six-inch armoured plating.

— Alfred Johnson, eye witness, BBC: "HMS Curacao Tragedy"

Acting under orders not to stop due to the risk of U-boat attacks, Queen Mary steamed onwards with a damaged bow. She radioed the other destroyers of her escort, about 7 nautical miles (13 km; 8.1 mi) away, and reported the collision. Hours later, the convoy's lead escort, consisting of Bramham and one other ship,[40] returned to rescue approximately 101 survivors, including Boutwood. Lost with Curacoa were 337 officers and men of her crew, according to the naval casualty file released by The National Archives in June 2013. Most of the lost men are commemorated on the Chatham Naval Memorial and the rest on the Portsmouth Naval Memorial. Those who died after rescue, or whose bodies were recovered, were buried in Chatham and in Arisaig Cemetery in Invernesshire. Under the Protection of Military Remains Act 1986, Curacoa's wrecksite is designated a "protected place".

Those who witnessed the collision were sworn to secrecy due to national security concerns. The loss was not publicly reported until after the war ended, although the Admiralty filed a writ against Queen Mary's owners, Cunard White Star Line, on 22 September 1943 in the Admiralty Court of the High Court of Justice. Little happened until 1945, when the case went to trial in June; it was adjourned to November and then to December 1946. Mr. Justice Pilcher exonerated the Queen Mary's crew and her owners from blame on 21 January 1947 and laid all fault on Curacoa's officers. The Admiralty appealed his ruling and the Court of Appeal modified the ruling, assigning two-thirds of the blame to the Admiralty and one third to Cunard White Star. The latter appealed to the House of Lords, but they upheld the decision.

The damaged bow of Queen Mary

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Curacoa_(D41)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/RMS_Queen_Mary

http://linerlogbook.blogspot.com/2014/09/needn-worryhe-will-keep-out-of-your-way.html

papers reported that there was a gale and a heavy sea at the time of the tragedy. The reports stated that there was perfect discipline aboard, and that the suddenness of the disaster and the hostile elements prevented lifesaving. Reports at the time indicated that there were 42 survivors and that although the first lifeboat escaped the second capsized. Survivors witnessed the crowded decks at the time the ship sank. All officers were lost.

papers reported that there was a gale and a heavy sea at the time of the tragedy. The reports stated that there was perfect discipline aboard, and that the suddenness of the disaster and the hostile elements prevented lifesaving. Reports at the time indicated that there were 42 survivors and that although the first lifeboat escaped the second capsized. Survivors witnessed the crowded decks at the time the ship sank. All officers were lost.