Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

9 November 1914 - Battle of Cocos - SMS Emden is sunk by HMAS Sydney - Part II

Battle

Wireless station capture

During the night of 8–9 November, Emden sailed to Direction Island. At 06:00 on 9 November, the ship anchored in the Cocos lagoon, deployed a steam pinnace (to tow a 50-strong landing party in two boats, led by Emden's first officer, Hellmuth von Mücke, ashore), and transmitted the coded summons for Buresk. The ship was spotted by off-duty personnel at the cable and wireless station, and although the ship was initially suspected to be Minotaur, the station's medical officer observed that the foremost funnel was false, and informed superintendent Darcy Farrant that it may be Emden in the bay. Farrant ordered the telegraphist on duty (already alerted by the German's coded signal) to begin transmitting a distress call by wireless and cable. Emden was able to jam the wireless signal shortly after it began, while the cable distress call continued until an armed party burst into the transmission room. Minotaur heard the wireless call and acknowledged, but von Müller was unconcerned, as the signal strength indicated that Minotaur was at least 10 hours away. Von Mücke instructed Farrant to surrender the keys to the station's buildings and any weapons, which the superintendent handed over, along with news that the Kaiser had announced awards for Emden's actions at Penang.

After taking control of the station and its 34 staff, German personnel smashed the transmitting equipment and severed two of the station's three undersea cables, plus a dummy cable. They also felled the main wireless mast; although taking care at the request of the staff to avoid damaging the station's tennis court, the mast landed on a cache of Scotch whisky. At around 09:00, lookouts on Emden saw smoke from an approaching ship. Initially assumed to be Buresk, by 09:15 she had been identified as an approaching warship, believed to be HMS Newcastle or another vessel of similar vintage. As Emden was prepared for battle, several signals were sent to the shore party to hurry up, but at 09:30, the raider had to raise anchor and sail to meet the approaching hostile ship, leaving von Mücke's party behind despite their best efforts to catch up.

The ANZAC convoy, positioned 80 kilometres (50 mi) north-east of the Cocos Islands, heard the coded Buresk summons, then the distress call from Direction Island. Believing the unidentified ship to be Emden or Königsberg (also believed to be at large in the region), Melbourne's captain, Mortimer Silver, ordered his ship to make full speed and turn for Cocos. Silver quickly realised that as commander of the convoy escort, he needed to remain with the troopships, and he reluctantly ordered Sydney to detach. Ibuki raised her battle ensign and requested permission to follow Sydney, but the Japanese ship was ordered to remain with the convoy. At 09:15, Sydney spotted Direction Island and the attacking ship. Confident of being able to outrun, outrange, and outshoot the German vessel, Glossop ordered the ship to prepare for action. He agreed with his gunnery officer to open fire at 9,500 yards (8,700 m): well within Sydney's firing range, but outside the believed range of Emden's guns.

Combat

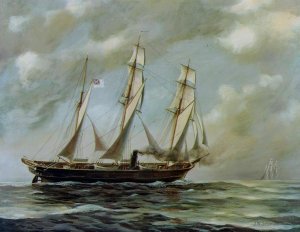

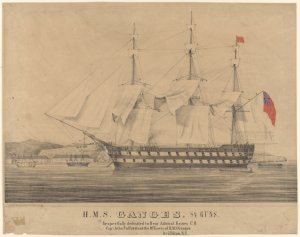

Japanese poster depicting the Battle of Cocos.

Emden was the first to fire at 09:40, and scored hits on her fourth salvo: two shells exploded near the aft control station and wrecked the aft rangefinders, while a third punched through the forward rangefinder and through the bridge without exploding. These shots landed at a range of approximately 10,000 yards (9,100 m); the 30-degree elevation of her main guns allowed her to fire much further than British estimates. Von Müller recognised that his success in the battle required Emden to do as much damage as possible before the other ship retaliated, but despite the heavy rate of fire from the Germans over the next ten minutes (at points reaching a salvo every six seconds), the high angle of the guns and the narrow profile presented by Sydney meant that only fifteen shells hit the Australian warship, of which only five exploded. As well as the rangefinders, damage was sustained to the S2 gun when a nearby impact sent hot shrapnel into the gun crew then ignited cordite charges being stored nearby for the fight, and another shell exploded in a forward mess deck. Four sailors were killed and another sixteen wounded; the only casualties aboard Sydney during the entire engagement.

Sydney attempted to open the gap between the two ships as she opened fire. This was hampered by the loss of both rangefinders, requiring each mounting to be targeted and fired locally. The first two salvoes missed, but two shells from the third struck: one exploding in Emden's wireless office, another by the Germans' forward gun. Heavy fire from Sydney damaged or destroyed Emden's steering gear, rangefinders, and the voicepipes to the turrets and engineering, and knocked out several guns. The forward funnel collapsed overboard, then the foremast fell and crushed the fore-bridge. A shell from Sydney landed in the aft ammunition room of Emden, and the Germans had to flood it or risk a massive explosion.

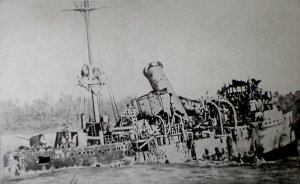

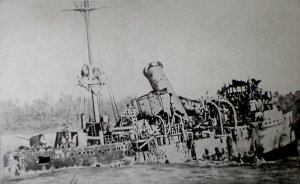

Emden beached on North Keeling Island

At around 10:20, the manoeuvring of the two ships brought them to within 5,500 yards (5,000 m), and Glossop took the opportunity to order a torpedo firing. The torpedo failed to cover the distance, and sank without exploding. The Australian ship sped up and turned to starboard so guns that had yet to fire could engage. Emden matched Sydney's turn, but by this point, the second funnel had been blasted off, and there was a fire in the engine room. In addition, about half of the cruiser's personnel had been killed or wounded, and the abandoning of the attack party on Direction Island meant there were no reserves to replace them. By 11:00, only one of Emden's guns was still firing. As the third funnel went overboard, Emden found herself closer to North Keeling Island, and von Müller ordered the ship to beach on North Keeling Island, hoping to prevent further loss of life. Emden ran aground at around 11:20, at which point, Sydney ceased fire. After Sydney contacted the convoy to report "Emden beached and done for", the soldiers aboard the troopships were granted a half-day holiday from duties and training to celebrate.

After Emden's beaching

Sydney then turned to pursue and capture Buresk, which had arrived on the horizon during the battle. The cruiser caught up shortly after 12:00 and fired a warning shot, but on closing with Buresk, Sydney found the collier had already commenced scuttling. Sydney recovered the boarding party and the crew from Buresk, fired four shells to hasten the collier's sinking, then once she had submerged, turned back towards North Keeling Island.

The Australian cruiser reached Emden around 16:00. The Germans' battle ensign was still flying, generally a sign that a ship intends to continue fighting. Sydney signalled "Do you surrender?" in international code by both lights and flag-hoist. The signal was not understood, and Emden responded with "What signal? No signal books". The instruction to surrender was repeated by Sydney in plain morse code, then after there was no reply, the message "Have you received my signal?" was sent. With no response forthcoming, and operating under the assumption that Emden could still potentially fire, launch torpedoes, or use small arms against any boarding parties, Glossop ordered Sydney to fire two salvoes into the wrecked ship. This attack killed 20 German personnel. The ensign was pulled down and burned, and a white sheet was raised over the quarter-deck as a flag of surrender. During the battle, 130 personnel aboard Emden were killed, and 69 were wounded, four of the latter died of their wounds.

Glossop had orders to ascertain the status of the transmission station, and left with Sydney to do so, after sending a boat with Buresk's crew to Emden with some medical supplies and a message that they would return the next day. In addition to checking on Direction Island, there was also the potential that Emden and Königsberg had been operating together and that the second ship would approach to recover the attack party from the island, or go after the troop convoy; consequently, Sydney could not render assistance to Emden's survivors until such threats had passed. It was too late to make a landing on Direction Island, so the cruiser spent the night patrolling the islands, and approached the wireless station the next morning. On arrival, the Australians learned that the Germans had escaped the previous evening in a commandeered schooner. Sydney embarked the island's doctor and two assistants, then headed for North Keeling Island.

Aftermath

The Australian cruiser reached the wreck of Emden at 13:00 on 10 November. After sending an officer over to receive assurance that the Germans would not fight, Glossop began a rescue operation. Transferring the German survivors from Emden to Sydney took about five hours, with the difficulty of transferring so many wounded, rough seas, and overcrowding aboard the Australian cruiser. The two Australian medical officers aboard Sydney and the medical staff from Direction Island worked from 18:00 on 10 November to 04:30 the next morning to clear the most pressing needs for medical attention, with Emden survivors prioritised. Some of the Germans had swum ashore after the beaching, and the difficulty of recovering them from the beach in the dark meant the rescue of the 20-odd survivors was put off until the morning of 11 November, although personnel from Sydney and Bureskwere sent ashore the previous evening with supplies. Most of 11 November was spent treating less pressing cases; the Direction Island staff left the ship around midday, and Emden's ship's surgeon, who had previously been unable to assist because of the shock and stress of caring for so many wounded from the battle's end until Sydney returned, had recovered enough by this point to assist as an anaesthetist.

On 12 November, the auxiliary cruiser Empress of Russia arrived, and the majority of the German personnel (excluding the officers and those too injured to be moved) were transferred over for transportation to Colombo. Sydney caught up to the ANZAC convoy at Colombo on 15 November. There were no celebrations of Sydney's success as the cruiser entered harbour: Glossop had signalled ahead to request that the sailors and soldiers aboard the warships and transports refrain from cheering, out of respect for the German wounded being carried aboard.

The wreck of Emden, some years after the battle

After Emden's defeat, the only German warship in the Indian Ocean basin was SMS Königsberg; the cruiser had been blockaded in the Rufiji River in October, and remained there until her destruction in July 1915. Australia was no longer under direct threat from the Central Powers, and many of the RAN ships designated for the nation's defence could be safely deployed to other theatres. Over the next two years, troop convoys from Australia and New Zealand to the Middle East sailed without naval escort, further freeing Allied resources. The state of affairs persisted until the raiders Wolf and Seeadler began operations in the region in 1917.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Cocos

9 November 1914 - Battle of Cocos - SMS Emden is sunk by HMAS Sydney - Part II

Battle

Wireless station capture

During the night of 8–9 November, Emden sailed to Direction Island. At 06:00 on 9 November, the ship anchored in the Cocos lagoon, deployed a steam pinnace (to tow a 50-strong landing party in two boats, led by Emden's first officer, Hellmuth von Mücke, ashore), and transmitted the coded summons for Buresk. The ship was spotted by off-duty personnel at the cable and wireless station, and although the ship was initially suspected to be Minotaur, the station's medical officer observed that the foremost funnel was false, and informed superintendent Darcy Farrant that it may be Emden in the bay. Farrant ordered the telegraphist on duty (already alerted by the German's coded signal) to begin transmitting a distress call by wireless and cable. Emden was able to jam the wireless signal shortly after it began, while the cable distress call continued until an armed party burst into the transmission room. Minotaur heard the wireless call and acknowledged, but von Müller was unconcerned, as the signal strength indicated that Minotaur was at least 10 hours away. Von Mücke instructed Farrant to surrender the keys to the station's buildings and any weapons, which the superintendent handed over, along with news that the Kaiser had announced awards for Emden's actions at Penang.

After taking control of the station and its 34 staff, German personnel smashed the transmitting equipment and severed two of the station's three undersea cables, plus a dummy cable. They also felled the main wireless mast; although taking care at the request of the staff to avoid damaging the station's tennis court, the mast landed on a cache of Scotch whisky. At around 09:00, lookouts on Emden saw smoke from an approaching ship. Initially assumed to be Buresk, by 09:15 she had been identified as an approaching warship, believed to be HMS Newcastle or another vessel of similar vintage. As Emden was prepared for battle, several signals were sent to the shore party to hurry up, but at 09:30, the raider had to raise anchor and sail to meet the approaching hostile ship, leaving von Mücke's party behind despite their best efforts to catch up.

The ANZAC convoy, positioned 80 kilometres (50 mi) north-east of the Cocos Islands, heard the coded Buresk summons, then the distress call from Direction Island. Believing the unidentified ship to be Emden or Königsberg (also believed to be at large in the region), Melbourne's captain, Mortimer Silver, ordered his ship to make full speed and turn for Cocos. Silver quickly realised that as commander of the convoy escort, he needed to remain with the troopships, and he reluctantly ordered Sydney to detach. Ibuki raised her battle ensign and requested permission to follow Sydney, but the Japanese ship was ordered to remain with the convoy. At 09:15, Sydney spotted Direction Island and the attacking ship. Confident of being able to outrun, outrange, and outshoot the German vessel, Glossop ordered the ship to prepare for action. He agreed with his gunnery officer to open fire at 9,500 yards (8,700 m): well within Sydney's firing range, but outside the believed range of Emden's guns.

Combat

Japanese poster depicting the Battle of Cocos.

Emden was the first to fire at 09:40, and scored hits on her fourth salvo: two shells exploded near the aft control station and wrecked the aft rangefinders, while a third punched through the forward rangefinder and through the bridge without exploding. These shots landed at a range of approximately 10,000 yards (9,100 m); the 30-degree elevation of her main guns allowed her to fire much further than British estimates. Von Müller recognised that his success in the battle required Emden to do as much damage as possible before the other ship retaliated, but despite the heavy rate of fire from the Germans over the next ten minutes (at points reaching a salvo every six seconds), the high angle of the guns and the narrow profile presented by Sydney meant that only fifteen shells hit the Australian warship, of which only five exploded. As well as the rangefinders, damage was sustained to the S2 gun when a nearby impact sent hot shrapnel into the gun crew then ignited cordite charges being stored nearby for the fight, and another shell exploded in a forward mess deck. Four sailors were killed and another sixteen wounded; the only casualties aboard Sydney during the entire engagement.

Sydney attempted to open the gap between the two ships as she opened fire. This was hampered by the loss of both rangefinders, requiring each mounting to be targeted and fired locally. The first two salvoes missed, but two shells from the third struck: one exploding in Emden's wireless office, another by the Germans' forward gun. Heavy fire from Sydney damaged or destroyed Emden's steering gear, rangefinders, and the voicepipes to the turrets and engineering, and knocked out several guns. The forward funnel collapsed overboard, then the foremast fell and crushed the fore-bridge. A shell from Sydney landed in the aft ammunition room of Emden, and the Germans had to flood it or risk a massive explosion.

Emden beached on North Keeling Island

At around 10:20, the manoeuvring of the two ships brought them to within 5,500 yards (5,000 m), and Glossop took the opportunity to order a torpedo firing. The torpedo failed to cover the distance, and sank without exploding. The Australian ship sped up and turned to starboard so guns that had yet to fire could engage. Emden matched Sydney's turn, but by this point, the second funnel had been blasted off, and there was a fire in the engine room. In addition, about half of the cruiser's personnel had been killed or wounded, and the abandoning of the attack party on Direction Island meant there were no reserves to replace them. By 11:00, only one of Emden's guns was still firing. As the third funnel went overboard, Emden found herself closer to North Keeling Island, and von Müller ordered the ship to beach on North Keeling Island, hoping to prevent further loss of life. Emden ran aground at around 11:20, at which point, Sydney ceased fire. After Sydney contacted the convoy to report "Emden beached and done for", the soldiers aboard the troopships were granted a half-day holiday from duties and training to celebrate.

After Emden's beaching

Sydney then turned to pursue and capture Buresk, which had arrived on the horizon during the battle. The cruiser caught up shortly after 12:00 and fired a warning shot, but on closing with Buresk, Sydney found the collier had already commenced scuttling. Sydney recovered the boarding party and the crew from Buresk, fired four shells to hasten the collier's sinking, then once she had submerged, turned back towards North Keeling Island.

The Australian cruiser reached Emden around 16:00. The Germans' battle ensign was still flying, generally a sign that a ship intends to continue fighting. Sydney signalled "Do you surrender?" in international code by both lights and flag-hoist. The signal was not understood, and Emden responded with "What signal? No signal books". The instruction to surrender was repeated by Sydney in plain morse code, then after there was no reply, the message "Have you received my signal?" was sent. With no response forthcoming, and operating under the assumption that Emden could still potentially fire, launch torpedoes, or use small arms against any boarding parties, Glossop ordered Sydney to fire two salvoes into the wrecked ship. This attack killed 20 German personnel. The ensign was pulled down and burned, and a white sheet was raised over the quarter-deck as a flag of surrender. During the battle, 130 personnel aboard Emden were killed, and 69 were wounded, four of the latter died of their wounds.

Glossop had orders to ascertain the status of the transmission station, and left with Sydney to do so, after sending a boat with Buresk's crew to Emden with some medical supplies and a message that they would return the next day. In addition to checking on Direction Island, there was also the potential that Emden and Königsberg had been operating together and that the second ship would approach to recover the attack party from the island, or go after the troop convoy; consequently, Sydney could not render assistance to Emden's survivors until such threats had passed. It was too late to make a landing on Direction Island, so the cruiser spent the night patrolling the islands, and approached the wireless station the next morning. On arrival, the Australians learned that the Germans had escaped the previous evening in a commandeered schooner. Sydney embarked the island's doctor and two assistants, then headed for North Keeling Island.

Aftermath

The Australian cruiser reached the wreck of Emden at 13:00 on 10 November. After sending an officer over to receive assurance that the Germans would not fight, Glossop began a rescue operation. Transferring the German survivors from Emden to Sydney took about five hours, with the difficulty of transferring so many wounded, rough seas, and overcrowding aboard the Australian cruiser. The two Australian medical officers aboard Sydney and the medical staff from Direction Island worked from 18:00 on 10 November to 04:30 the next morning to clear the most pressing needs for medical attention, with Emden survivors prioritised. Some of the Germans had swum ashore after the beaching, and the difficulty of recovering them from the beach in the dark meant the rescue of the 20-odd survivors was put off until the morning of 11 November, although personnel from Sydney and Bureskwere sent ashore the previous evening with supplies. Most of 11 November was spent treating less pressing cases; the Direction Island staff left the ship around midday, and Emden's ship's surgeon, who had previously been unable to assist because of the shock and stress of caring for so many wounded from the battle's end until Sydney returned, had recovered enough by this point to assist as an anaesthetist.

On 12 November, the auxiliary cruiser Empress of Russia arrived, and the majority of the German personnel (excluding the officers and those too injured to be moved) were transferred over for transportation to Colombo. Sydney caught up to the ANZAC convoy at Colombo on 15 November. There were no celebrations of Sydney's success as the cruiser entered harbour: Glossop had signalled ahead to request that the sailors and soldiers aboard the warships and transports refrain from cheering, out of respect for the German wounded being carried aboard.

The wreck of Emden, some years after the battle

After Emden's defeat, the only German warship in the Indian Ocean basin was SMS Königsberg; the cruiser had been blockaded in the Rufiji River in October, and remained there until her destruction in July 1915. Australia was no longer under direct threat from the Central Powers, and many of the RAN ships designated for the nation's defence could be safely deployed to other theatres. Over the next two years, troop convoys from Australia and New Zealand to the Middle East sailed without naval escort, further freeing Allied resources. The state of affairs persisted until the raiders Wolf and Seeadler began operations in the region in 1917.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Cocos

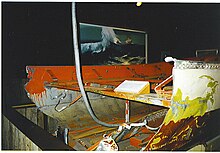

of USS Mount Hood (AE-11) in Seeadler Harbor, Manus, Admiralty Islands, 10 November 1944. Small craft gathered around USS Mindanao (ARG-3) during salvage and rescue efforts shortly after Mount Hoodblew up about 350 yards away from Mindanao's port side. Mindanao, and seven motor minesweepers (YMS) moored to her starboard side, were damaged by the blast, as were the

of USS Mount Hood (AE-11) in Seeadler Harbor, Manus, Admiralty Islands, 10 November 1944. Small craft gathered around USS Mindanao (ARG-3) during salvage and rescue efforts shortly after Mount Hoodblew up about 350 yards away from Mindanao's port side. Mindanao, and seven motor minesweepers (YMS) moored to her starboard side, were damaged by the blast, as were the

week

week