Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

19 December 1796 - HMS Courageux (1753/1761 - 74), Lt. John Burrows (Act.), struck on rocks under Apes' Hill, coast of Barbary.

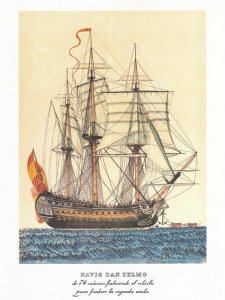

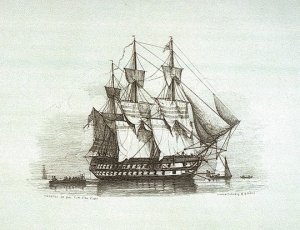

Courageux was a heavy 74-gun ship of the line of the French Navy, launched in 1753. She was captured by the Royal Navy in 1761 and taken into service as HMS Courageux. She was wrecked in 1796.

Class and type: 74-gun third-rate ship of the line

Tons burthen: 1,721 bm

Length: 140 ft 10 3⁄8 in (42.9 m) (gundeck)

Beam: 48 ft (14.6 m)

Depth of hold: 20 ft 10 1⁄2 in (6.4 m)

Sail plan: Full-rigged ship

Armament:

Design

Courageux was a 74-gun ship-of-the-line of the French Royal Navy. Her keel of 140 feet 1 1⁄8 inches (42.7 m) was laid down at Brest in April 1751 and her dimensions as built were: 172 feet 3 inches (52.5 m) along the gun deck, with a beam of 48 feet 0 3⁄4 inch (14.6 m) and a depth in the hold of 20 feet 10 1⁄2 inches (6.4 m). At 1,721 30⁄94 tons burthen she was of a typical size for a French 74 which were at least 100 tons heavier than their British equivalents. She was considered heavy because she carried 24-pounder guns on her upper deck rather than the normal 18 pounders. and when fully manned, she would have carried a complement of 650 men.

While in Royal Navy service, she was armed with up to twenty-eight 18-pound guns on her upper deck and the same amount of 32-pounders on the lower deck. Her upper works carried 9-pound guns; fourteen on the quarterdeck and four on the forecastle.

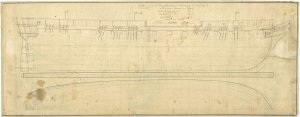

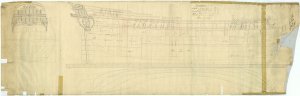

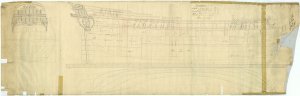

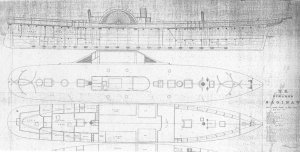

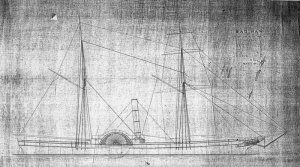

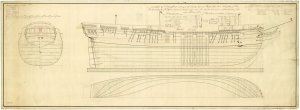

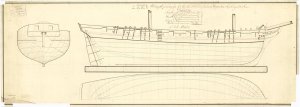

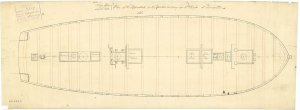

Scale: 1:48. Plan showing the body plan with stern board decoration and name in a cartouche on the counter, the sheer lines with inboard detail and figurehead, and the longitudinal half-breadth for 'Courageux' (1761), a captured French Third Rate, as taken off prior to fitting as a 74-gun Third Rate, two-decker at Portsmouth Dockyard. Signed by Edward Allin [Master Shipwright, Portsmouth Dockyard, 1755-1762] Reverse: Scale: 1:96. Plan showing the roundhouse, quarterdeck and forecastle, upper deck, gun (lower) deck, and orlop deck with fore and aft platforms for 'Courageux' (1762).

Service

Main article: Action of 14 August 1761

On 13 August 1761, Courageux was off Vigo in the company of two frigates, when she was captured by the 74-gun British ship HMS Bellona. Courageux sighted Bellona in company with the frigate Brilliant. The British ships pursued, and after 14 hours, caught up with the French ships and engaged, the Brilliant attacking the frigates, and Bellona taking on Courageux. The frigates eventually got away, but Courageux struck her colours.

She was purchased by the Admiralty on 2 February the following year, for £9,797.16.4, and taken into the Royal Navy as the third rate HMS Courageux. Another £22,380.11.4d was invested in July when a large repair was made at Portsmouth and which took until the middle of June 1764 to complete. A further substantial repair was made between January 1772 and July 1773, the price for which was £16,420.19.10d.

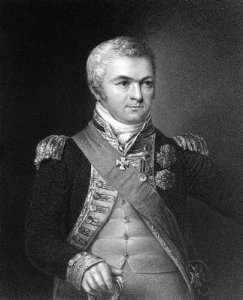

In July 1776, Courageux was commissioned under Captain Samuel Hood and in November, £10,132.6.2d was spent having her fitted out as a guardship at Portsmouth. Between April and May 1779, she underwent another refit, which included the sheathing of her hull with copper, and cost £7,468.7.0d. An £8,547.17.7d refit was carried out in April 1782. Then in June 1787 a great repair was required, costing £30,369.13.4d and taking until July 1789. Following a dispute with Spain over territorial rights along the Nootka Sound, Courageux was commissioned in April 1790, under George Countess for the Spanish Armament. The crisis was largely resolved through a series of agreements signed between October 1790 and January 1794. In February 1791, Alan Gardner was in command, when Courageux was recommissioned for the Russian Armament. Again, the matter was settled before she was called into action and she paid off in September that year.

Toulon

Main article: Siege of Toulon

France declared war on Britain and the Dutch Republic in February 1793, and in the Spring Courageux, under William Waldegrave, was sent with other British ships to blockade the French fleet in Toulon. By the middle of August, this British force, under Hood in the 100-gun HMS Victory, had grown to 21 ships-of-the-line. On 23 August, a deputation of French royalists came aboard Victory to discuss the conditional surrender of the town and on 27 August 1500 troops were landed to remove the republicans occupying the forts guarding the port. Hood's fleet, accompanied by 17 Spanish ships-of-the-line which had just arrived, then sailed into the harbour.

In September, French troops laid siege to the city and in December, the allied force within was driven out. When the order to withdraw was given, Courageux was being repaired and was without a rudder, but was able to warp out of the harbour and assist in the evacuation of allied troops from the waterfront. A replacement rudder was brought out, suspended between two ship's boats, and fitted later.

Corsica

Main article: Invasion of Corsica (1794)

In September 1793, during the occupation of Toulon, Courageux joined a squadron under Robert Linzee, which was sent to Corsica to support an insurrection there. General Pasquale Paoli, the leader of the insurgent party, had assured Hood that a small show of strength was all that was needed to force the island's surrender. This turned out not to be the case however, and Linzee's appeals to the French garrisons there were rejected. His force, of three ships-of-the-line and two frigates, was too small to blockade the island and starve it into submission, so an attack on San Fiorenzo was decided upon.

The two frigates, Lowestoffe and Nemesis, were charged with destroying a Martello tower at Forneilli, two miles from the town, which guarded the only secure anchorage in the bay. After taking a few salvos from the ships, the French garrison deserted and the British landed men to secure the fort. Linzee's squadron entered the bay but was prevented from engaging the batteries of San Fiorenzo by contrary winds. During the night, HMS Ardent was warped into a position where, at 03:30 on 1 October, she was able to attack the batteries and cover the approach of the other British ships. Half-an-hour later, HMS Alcide tried to take up a station nearby but was blown towards some rocks by a sudden change of wind and had to be towed clear.Courageux in the meantime covered Alcide's stern by coming between it and the gunfire from a redoubt on the shore. Alcide, eventually got into a position where she could join in the action and the three ships bombarded the redoubt until 08:15 when, there being little sign of damage, Linzee gave the order to withdraw. Courageux bore the brunt of the action, having been exposed to a raking fire from the town, and had been on fire four times, after being hit by heated shot.

Battle of Genoa

Main article: Battle of Genoa

Courageux was one of 13 ships-of-the-line which, together with seven frigates, two sloops and a cutter, were anchored in the roads of Livorno on 8 March 1795. The following day, a British scout, the 24-gun sloop Moselle, brought news that a French fleet of 15 ships-of-the-line, six frigates and two brigs, had been seen off the islands of Sainte-Marguerite. Hotham immediately set off in pursuit and on 10 March the advanced British frigates spotted the French fleet at some distance, making its way back to Toulon against the wind. Two days later, on the night of 12 March, a storm developed which badly damaged two French ships-of-the-line. These ships were escorted to Gourjean Bay by two French frigates, leaving the opposing fleets roughly equal in strength and number.

The next morning, Hotham attempted to get his ships into a form line but seeing no response from the French fleet, changed his orders to general chase. At 08:00 the 80-gun Ça Ira at the rear, collided with Victoire and her fore and main topmasts collapsed overboard. The leading British ship was the 36-gun frigate, HMS Inconstant under Captain Thomas Fremantle, which reached the damaged Ça Ira within an hour of the collision and opened fire at close range, causing further damage. Seeing the danger, the French frigate, Vestale fired upon Inconstant from a distance before taking the limping Ça Ira in tow.

Throughout the day and the following night, the British van sporadically engaged the French rearguard, with Ça Ira dropping further behind the main body of the French force. In order to better protect the damaged ship, the French admiral, Pierre Martin ordered the ship of the line, Censeur to replace Vestale as the towing ship. By morning the fleets were 21 nautical miles (39 km) south-west of Genoa with the British rapidly gaining ground. Ça Ira and Censeur had fallen further behind, and Hotham sent his two fastest ships after them. Captain and Bedford did not arrive simultaneously however, and were both repulsed, although further damage was inflicted on the French stragglers in the process. Martin, ordered his line to wear in succession and get between the British fleet and the badly damaged Ça Ira and Censeur, which in the meantime had come under a new threat from the recently arrived Courageux and HMS Illustrious. A sudden drop in wind made manoeuvres difficult and the leading French ship Duquesne under Captain Zacharie Allemand, found itself sailing down the other side of the British vanguard.

At 08:00, Duquesne was in a position to engage Illustrious and Courageux which, in their efforts to reach Ça Ira and Censeur, were now far ahead and to leeward of their line. Two other French ships, Victoire and Tonnant, joined the action and for an hour, the French and British vanguards exchanged heavy fire. Both British ships were heavily damaged: Illustrious had drifted out of the battle having lost her main and mizzen mast over the side, while Courageux also had two masts down, and her hull much holed by French shot. The Duquesne, Victoire, and Tonnant, then exchanged passing shots with the British ships coming up, before turning away and leaving Ça Ira and Censeur to their fate. Hotham, considering that his van-ships were not in a condition to, and content with his prizes, did not pursue.

Action off Hyeres

The fleet was re-victualling in San Fiorenzo bay on 8 July 1795, when a small squadron under Commodore Horatio Nelson approached, followed by the French Fleet from Toulon. The British fleet was not able to put to sea immediately due to contrary winds but was spotted by the French, who abandoned their chase. Hotham finished refitting and supplying his ships, and finally managed to set off after his quarry at 21:00; almost twelve hours later. On the night of 12 July, the British ships were hit by a storm and were still carrying out repairs the following morning when the French fleet was sighted. At 03:45 Hotham gave the order to make all possible sail in pursuit of their enemy, which by then was 5 nautical miles (9.3 km) away, bearing towards Fréjus.

By 08:00, the French had formed a tight line-of-battle but the British ships were strung out over an 8 nmi (15 km) distance. The leading British ships, Victory, Culloden, and Cumberland, at 3⁄4 nmi (1.4 km), were within range and opened fire. After six hours, as more ships were arriving, one of the rearmost French ships, Alcide struck. Before the British could take possession of her however she caught fire and exploded. Courageux, under the command of Benjamin Hallowell, and some way back, was unable to get into the action before Hotham, believing the fleet to be running out of sea-room, signalled to disengage.

Fate

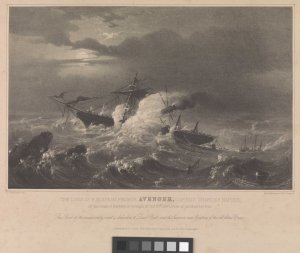

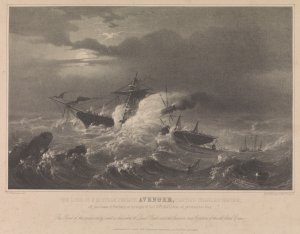

In December 1796, Courageux was with Jervis' fleet, anchored in the bay of Gibraltar, when a great storm tore her from her mooring and drove her onto the rocks. Sources differ as to when this occurred and the number of lives lost. William James records that on 10 December a French squadron under Admiral Villeneuve, left the Mediterranean but the British were unable to pursue due to a strong leeshore wind. The weather took a turn for the worse and that very night, several ships cut or had their cables snapped, including HMS Culloden and HMS Gibraltar.

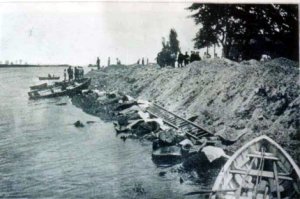

When Courageux parted from her anchor, Captain Benjamin Hallowell was ashore at Gibraltar, serving on a court-martial, and Lieutenant John Burrows was in command. She drifted across the bay and under the guns of the Spanish batteries and from there, under close-reefed topsails, made her way towards the Barbary coast; Burrows reluctant to run through the Straits for fear of falling in with Villeneuve's ships. Towards evening, the wind and rain increased to hurricane force, and soon after 20:00, the crew, who had been exhausted from trying to sail the ship out of trouble, were sent to dinner. The officers, except a lieutenant of the watch, also retired below. At 21:00, when land was sighted, there were too few men available to prevent the Courageux hitting the rocks at the foot of Ape's hill (Mons Abyla), on the coast of Barbary. She broadsided, lost her masts over the side, and water entered at a rapid rate as waves and winds battered her. Of the 593 officers and men that were on board, 129 only effected their escape; five by means of the launch that was towing astern, and the remainder by passing along the fallen mainmast to the rugged shore.

Lloyd's List stated that she had been lost in a gale on 12 December that also resulted in several transport vessels and merchant ships being driven on shore, with the Spaniards capturing the transports. Lloyd's List reported that only five people had been saved from Courageux. In the first printings of his book, "The Naval History of Great Britain, Volume I, (1793-1796)", James gave the date of the wrecking as 17 but this is changed to 10 from the second edition on. David Hepper says it occurred on 18, as does David Steel in "Steel's Naval Remembrancer: From the Commencement of the War in 1793 to the End of the Year 1800". John Marshall in his "Royal Naval Biography (Volume I, Part II)" says 19.

Scale 1:48. Plan showing the body plan, sheer lines, and longitudinal half-breadth for 'Colossus' (1787), 'Leviathan' (1790), 'Carnatic' (1783), and 'Minotaur' (1793), all 74-gun Third Rate, two-deckers based on the lines for the captured French Third Rate 'Courageux' (captured 1761). Signed by John Williams [Surveyor of the Navy, 1765-1784] and Edward Hunt [Surveyor of the Navy 1778-1784].

Scale: 1:48. Plan showing the body plan, sheer lines, and longitudinal half-breadth for Blake (1809) and Saint Domingo (1808), both 74-gun Third Rate, two-decker. These two ships were a lenghtened version of the Courageux (captured 1761), a captured French 74-gun Third Rate. Signed by John Henslow [Surveyor of the Navy, 1784-1806] and William Rule [Surveyor of the Navy, 1793-1813].

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_ship_Courageux_(1753)

19 December 1796 - HMS Courageux (1753/1761 - 74), Lt. John Burrows (Act.), struck on rocks under Apes' Hill, coast of Barbary.

Courageux was a heavy 74-gun ship of the line of the French Navy, launched in 1753. She was captured by the Royal Navy in 1761 and taken into service as HMS Courageux. She was wrecked in 1796.

Class and type: 74-gun third-rate ship of the line

Tons burthen: 1,721 bm

Length: 140 ft 10 3⁄8 in (42.9 m) (gundeck)

Beam: 48 ft (14.6 m)

Depth of hold: 20 ft 10 1⁄2 in (6.4 m)

Sail plan: Full-rigged ship

Armament:

- French Navy: 74 guns

- Gundeck: 28 × 36-pounders

- Upper gundeck: 30 × 24-pounders

- Quarterdeck: 16 × 8-pounders

- Royal Navy: 74 guns

- Gundeck: 28 × 32-pounders

- Upper gundeck: 28 × 18-pounders

- Quarterdeck: 18 × 9-pounders

Design

Courageux was a 74-gun ship-of-the-line of the French Royal Navy. Her keel of 140 feet 1 1⁄8 inches (42.7 m) was laid down at Brest in April 1751 and her dimensions as built were: 172 feet 3 inches (52.5 m) along the gun deck, with a beam of 48 feet 0 3⁄4 inch (14.6 m) and a depth in the hold of 20 feet 10 1⁄2 inches (6.4 m). At 1,721 30⁄94 tons burthen she was of a typical size for a French 74 which were at least 100 tons heavier than their British equivalents. She was considered heavy because she carried 24-pounder guns on her upper deck rather than the normal 18 pounders. and when fully manned, she would have carried a complement of 650 men.

While in Royal Navy service, she was armed with up to twenty-eight 18-pound guns on her upper deck and the same amount of 32-pounders on the lower deck. Her upper works carried 9-pound guns; fourteen on the quarterdeck and four on the forecastle.

Scale: 1:48. Plan showing the body plan with stern board decoration and name in a cartouche on the counter, the sheer lines with inboard detail and figurehead, and the longitudinal half-breadth for 'Courageux' (1761), a captured French Third Rate, as taken off prior to fitting as a 74-gun Third Rate, two-decker at Portsmouth Dockyard. Signed by Edward Allin [Master Shipwright, Portsmouth Dockyard, 1755-1762] Reverse: Scale: 1:96. Plan showing the roundhouse, quarterdeck and forecastle, upper deck, gun (lower) deck, and orlop deck with fore and aft platforms for 'Courageux' (1762).

Service

Main article: Action of 14 August 1761

On 13 August 1761, Courageux was off Vigo in the company of two frigates, when she was captured by the 74-gun British ship HMS Bellona. Courageux sighted Bellona in company with the frigate Brilliant. The British ships pursued, and after 14 hours, caught up with the French ships and engaged, the Brilliant attacking the frigates, and Bellona taking on Courageux. The frigates eventually got away, but Courageux struck her colours.

She was purchased by the Admiralty on 2 February the following year, for £9,797.16.4, and taken into the Royal Navy as the third rate HMS Courageux. Another £22,380.11.4d was invested in July when a large repair was made at Portsmouth and which took until the middle of June 1764 to complete. A further substantial repair was made between January 1772 and July 1773, the price for which was £16,420.19.10d.

In July 1776, Courageux was commissioned under Captain Samuel Hood and in November, £10,132.6.2d was spent having her fitted out as a guardship at Portsmouth. Between April and May 1779, she underwent another refit, which included the sheathing of her hull with copper, and cost £7,468.7.0d. An £8,547.17.7d refit was carried out in April 1782. Then in June 1787 a great repair was required, costing £30,369.13.4d and taking until July 1789. Following a dispute with Spain over territorial rights along the Nootka Sound, Courageux was commissioned in April 1790, under George Countess for the Spanish Armament. The crisis was largely resolved through a series of agreements signed between October 1790 and January 1794. In February 1791, Alan Gardner was in command, when Courageux was recommissioned for the Russian Armament. Again, the matter was settled before she was called into action and she paid off in September that year.

Toulon

Main article: Siege of Toulon

France declared war on Britain and the Dutch Republic in February 1793, and in the Spring Courageux, under William Waldegrave, was sent with other British ships to blockade the French fleet in Toulon. By the middle of August, this British force, under Hood in the 100-gun HMS Victory, had grown to 21 ships-of-the-line. On 23 August, a deputation of French royalists came aboard Victory to discuss the conditional surrender of the town and on 27 August 1500 troops were landed to remove the republicans occupying the forts guarding the port. Hood's fleet, accompanied by 17 Spanish ships-of-the-line which had just arrived, then sailed into the harbour.

In September, French troops laid siege to the city and in December, the allied force within was driven out. When the order to withdraw was given, Courageux was being repaired and was without a rudder, but was able to warp out of the harbour and assist in the evacuation of allied troops from the waterfront. A replacement rudder was brought out, suspended between two ship's boats, and fitted later.

Corsica

Main article: Invasion of Corsica (1794)

In September 1793, during the occupation of Toulon, Courageux joined a squadron under Robert Linzee, which was sent to Corsica to support an insurrection there. General Pasquale Paoli, the leader of the insurgent party, had assured Hood that a small show of strength was all that was needed to force the island's surrender. This turned out not to be the case however, and Linzee's appeals to the French garrisons there were rejected. His force, of three ships-of-the-line and two frigates, was too small to blockade the island and starve it into submission, so an attack on San Fiorenzo was decided upon.

The two frigates, Lowestoffe and Nemesis, were charged with destroying a Martello tower at Forneilli, two miles from the town, which guarded the only secure anchorage in the bay. After taking a few salvos from the ships, the French garrison deserted and the British landed men to secure the fort. Linzee's squadron entered the bay but was prevented from engaging the batteries of San Fiorenzo by contrary winds. During the night, HMS Ardent was warped into a position where, at 03:30 on 1 October, she was able to attack the batteries and cover the approach of the other British ships. Half-an-hour later, HMS Alcide tried to take up a station nearby but was blown towards some rocks by a sudden change of wind and had to be towed clear.Courageux in the meantime covered Alcide's stern by coming between it and the gunfire from a redoubt on the shore. Alcide, eventually got into a position where she could join in the action and the three ships bombarded the redoubt until 08:15 when, there being little sign of damage, Linzee gave the order to withdraw. Courageux bore the brunt of the action, having been exposed to a raking fire from the town, and had been on fire four times, after being hit by heated shot.

Battle of Genoa

Main article: Battle of Genoa

Courageux was one of 13 ships-of-the-line which, together with seven frigates, two sloops and a cutter, were anchored in the roads of Livorno on 8 March 1795. The following day, a British scout, the 24-gun sloop Moselle, brought news that a French fleet of 15 ships-of-the-line, six frigates and two brigs, had been seen off the islands of Sainte-Marguerite. Hotham immediately set off in pursuit and on 10 March the advanced British frigates spotted the French fleet at some distance, making its way back to Toulon against the wind. Two days later, on the night of 12 March, a storm developed which badly damaged two French ships-of-the-line. These ships were escorted to Gourjean Bay by two French frigates, leaving the opposing fleets roughly equal in strength and number.

The next morning, Hotham attempted to get his ships into a form line but seeing no response from the French fleet, changed his orders to general chase. At 08:00 the 80-gun Ça Ira at the rear, collided with Victoire and her fore and main topmasts collapsed overboard. The leading British ship was the 36-gun frigate, HMS Inconstant under Captain Thomas Fremantle, which reached the damaged Ça Ira within an hour of the collision and opened fire at close range, causing further damage. Seeing the danger, the French frigate, Vestale fired upon Inconstant from a distance before taking the limping Ça Ira in tow.

Throughout the day and the following night, the British van sporadically engaged the French rearguard, with Ça Ira dropping further behind the main body of the French force. In order to better protect the damaged ship, the French admiral, Pierre Martin ordered the ship of the line, Censeur to replace Vestale as the towing ship. By morning the fleets were 21 nautical miles (39 km) south-west of Genoa with the British rapidly gaining ground. Ça Ira and Censeur had fallen further behind, and Hotham sent his two fastest ships after them. Captain and Bedford did not arrive simultaneously however, and were both repulsed, although further damage was inflicted on the French stragglers in the process. Martin, ordered his line to wear in succession and get between the British fleet and the badly damaged Ça Ira and Censeur, which in the meantime had come under a new threat from the recently arrived Courageux and HMS Illustrious. A sudden drop in wind made manoeuvres difficult and the leading French ship Duquesne under Captain Zacharie Allemand, found itself sailing down the other side of the British vanguard.

At 08:00, Duquesne was in a position to engage Illustrious and Courageux which, in their efforts to reach Ça Ira and Censeur, were now far ahead and to leeward of their line. Two other French ships, Victoire and Tonnant, joined the action and for an hour, the French and British vanguards exchanged heavy fire. Both British ships were heavily damaged: Illustrious had drifted out of the battle having lost her main and mizzen mast over the side, while Courageux also had two masts down, and her hull much holed by French shot. The Duquesne, Victoire, and Tonnant, then exchanged passing shots with the British ships coming up, before turning away and leaving Ça Ira and Censeur to their fate. Hotham, considering that his van-ships were not in a condition to, and content with his prizes, did not pursue.

Action off Hyeres

The fleet was re-victualling in San Fiorenzo bay on 8 July 1795, when a small squadron under Commodore Horatio Nelson approached, followed by the French Fleet from Toulon. The British fleet was not able to put to sea immediately due to contrary winds but was spotted by the French, who abandoned their chase. Hotham finished refitting and supplying his ships, and finally managed to set off after his quarry at 21:00; almost twelve hours later. On the night of 12 July, the British ships were hit by a storm and were still carrying out repairs the following morning when the French fleet was sighted. At 03:45 Hotham gave the order to make all possible sail in pursuit of their enemy, which by then was 5 nautical miles (9.3 km) away, bearing towards Fréjus.

By 08:00, the French had formed a tight line-of-battle but the British ships were strung out over an 8 nmi (15 km) distance. The leading British ships, Victory, Culloden, and Cumberland, at 3⁄4 nmi (1.4 km), were within range and opened fire. After six hours, as more ships were arriving, one of the rearmost French ships, Alcide struck. Before the British could take possession of her however she caught fire and exploded. Courageux, under the command of Benjamin Hallowell, and some way back, was unable to get into the action before Hotham, believing the fleet to be running out of sea-room, signalled to disengage.

Fate

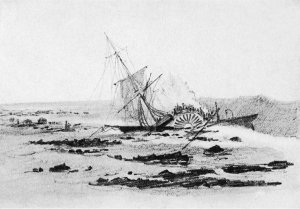

In December 1796, Courageux was with Jervis' fleet, anchored in the bay of Gibraltar, when a great storm tore her from her mooring and drove her onto the rocks. Sources differ as to when this occurred and the number of lives lost. William James records that on 10 December a French squadron under Admiral Villeneuve, left the Mediterranean but the British were unable to pursue due to a strong leeshore wind. The weather took a turn for the worse and that very night, several ships cut or had their cables snapped, including HMS Culloden and HMS Gibraltar.

When Courageux parted from her anchor, Captain Benjamin Hallowell was ashore at Gibraltar, serving on a court-martial, and Lieutenant John Burrows was in command. She drifted across the bay and under the guns of the Spanish batteries and from there, under close-reefed topsails, made her way towards the Barbary coast; Burrows reluctant to run through the Straits for fear of falling in with Villeneuve's ships. Towards evening, the wind and rain increased to hurricane force, and soon after 20:00, the crew, who had been exhausted from trying to sail the ship out of trouble, were sent to dinner. The officers, except a lieutenant of the watch, also retired below. At 21:00, when land was sighted, there were too few men available to prevent the Courageux hitting the rocks at the foot of Ape's hill (Mons Abyla), on the coast of Barbary. She broadsided, lost her masts over the side, and water entered at a rapid rate as waves and winds battered her. Of the 593 officers and men that were on board, 129 only effected their escape; five by means of the launch that was towing astern, and the remainder by passing along the fallen mainmast to the rugged shore.

Lloyd's List stated that she had been lost in a gale on 12 December that also resulted in several transport vessels and merchant ships being driven on shore, with the Spaniards capturing the transports. Lloyd's List reported that only five people had been saved from Courageux. In the first printings of his book, "The Naval History of Great Britain, Volume I, (1793-1796)", James gave the date of the wrecking as 17 but this is changed to 10 from the second edition on. David Hepper says it occurred on 18, as does David Steel in "Steel's Naval Remembrancer: From the Commencement of the War in 1793 to the End of the Year 1800". John Marshall in his "Royal Naval Biography (Volume I, Part II)" says 19.

Scale 1:48. Plan showing the body plan, sheer lines, and longitudinal half-breadth for 'Colossus' (1787), 'Leviathan' (1790), 'Carnatic' (1783), and 'Minotaur' (1793), all 74-gun Third Rate, two-deckers based on the lines for the captured French Third Rate 'Courageux' (captured 1761). Signed by John Williams [Surveyor of the Navy, 1765-1784] and Edward Hunt [Surveyor of the Navy 1778-1784].

Scale: 1:48. Plan showing the body plan, sheer lines, and longitudinal half-breadth for Blake (1809) and Saint Domingo (1808), both 74-gun Third Rate, two-decker. These two ships were a lenghtened version of the Courageux (captured 1761), a captured French 74-gun Third Rate. Signed by John Henslow [Surveyor of the Navy, 1784-1806] and William Rule [Surveyor of the Navy, 1793-1813].

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_ship_Courageux_(1753)

ed off Philadelphia to repair damage caused by a lightning strike

ed off Philadelphia to repair damage caused by a lightning strike

er's Bay. PvdM 9/04]

er's Bay. PvdM 9/04]