Today in Naval History - Naval / Maritime Events in History

27 February 1869 – Launch of HMS Volage, a Volage-class corvette built for the Royal Navy in the late 1860s.

HMS Volage was a Volage-class corvette built for the Royal Navy in the late 1860s. She spent most of her first commission assigned to the Flying Squadron circumnavigating the world and later carried a party of astronomers to the Kerguelen Islands to observe the transit of Venus in 1874. The ship was then assigned as the senior officer's ship in South American waters until she was transferred to the Training Squadron during the 1880s. Volage was paid off in 1899 and sold for scrap in 1904.

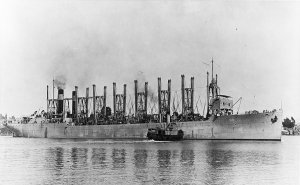

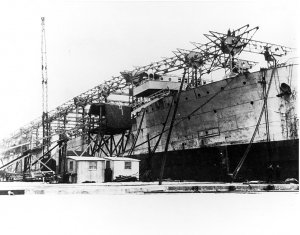

Circa 1892 photograph of HMS Volage, lead ship of the class

Description

Volage was 270 feet (82.3 m) long between perpendiculars and had a beam of 42 feet 1 inch (12.8 m). Forward the ship had a draught of 16 feet 5 inches (5.0 m), but aft she drew 21 ft 5 in (6.5 m). Volage displaced 3,078 long tons (3,127 t) and had a burthen of 2,322 tons. Her iron hull was covered by a 3-inch (76 mm) layer of oak that was sheathed with copper from the waterline down to prevent biofouling. Watertight transverse bulkheads subdivided the hull. Her crew consisted of 340 officers and enlisted men. The ship was nicknamed Vollidge by her crew.

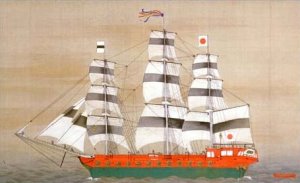

The ship had one 2-cylinder trunk engine made by John Penn & Sons driving a single 19-foot (5.8 m) propeller. Five rectangular boilers provided steam to the engine at a working pressure of 30 psi (207 kPa; 2 kgf/cm2). The engine produced a total of 4,530 indicated horsepower (3,380 kW) which gave Volage a maximum speed of 15.3 knots (28.3 km/h; 17.6 mph). The ship carried 420 long tons (430 t) of coal, enough to steam 1,850 nautical miles (3,430 km; 2,130 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). Volage was ship rigged and had a sail area of 16,593 square feet (1,542 m2). The lower masts were made of iron, but the other masts were wood. The ship's best speed under sail alone was 13 knots (24 km/h; 15 mph). Her funnel was semi-retractable to reduce wind resistance and her propeller could be hoisted up into the stern of the ship to reduce drag while under sail.

The ship was initially armed with a mix of 7-inch and 64-pounder 64 cwt rifled muzzle-loading guns. The six 7-inch (178 mm) guns and two of the four 64-pounders were mounted on the broadside while the other two were mounted on the forecastle and poop deck as chase guns. The 7-inch guns were replaced in 1873 and the ship was rearmed with a total of eighteen 64-pounders. In 1880, ten BL 6-inch 80-pounder breech-loading guns replaced all the broadside weapons. Two carriages for 14-inch (356 mm) torpedoes were added as well.

Service

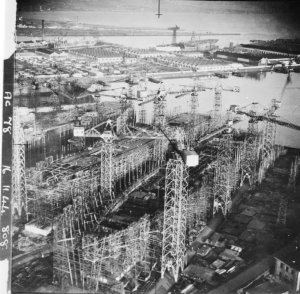

HMS Volage was laid down in September 1867 and launched on 27 February 1869. The ship was completed in March 1870 at a total cost of £132,817. Of this, £91,817 was spent on her hull and £41,000 on her machinery. Volage was initially assigned to the Channel Fleet under the command of Captain Sir Michael Culme-Seymour, Bt. However, by the end of 1870, she was transferred to the Flying Squadron which circumnavigated the world. The ship returned to England at the end of 1872 and was given a lengthy refit. Volage recommissioned in 1874 to ferry an expedition of astronomers to the Kerguelen Islands to observe the transit of Venus. She grounded on an uncharted shoal there without damage. The following year, the ship was assigned as the senior officer's ship for the South American side of the South Atlantic. Volage was ordered home in 1879 where she was refitted, rearmed and her boilers were replaced. The ship was assigned to the Training Squadron in the 1880s until it was disbanded in 1899. Volagewas then paid off and sold for scrap on 17 May 1904.

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

27 February 1869 – Launch of HMS Volage, a Volage-class corvette built for the Royal Navy in the late 1860s.

HMS Volage was a Volage-class corvette built for the Royal Navy in the late 1860s. She spent most of her first commission assigned to the Flying Squadron circumnavigating the world and later carried a party of astronomers to the Kerguelen Islands to observe the transit of Venus in 1874. The ship was then assigned as the senior officer's ship in South American waters until she was transferred to the Training Squadron during the 1880s. Volage was paid off in 1899 and sold for scrap in 1904.

Circa 1892 photograph of HMS Volage, lead ship of the class

Description

Volage was 270 feet (82.3 m) long between perpendiculars and had a beam of 42 feet 1 inch (12.8 m). Forward the ship had a draught of 16 feet 5 inches (5.0 m), but aft she drew 21 ft 5 in (6.5 m). Volage displaced 3,078 long tons (3,127 t) and had a burthen of 2,322 tons. Her iron hull was covered by a 3-inch (76 mm) layer of oak that was sheathed with copper from the waterline down to prevent biofouling. Watertight transverse bulkheads subdivided the hull. Her crew consisted of 340 officers and enlisted men. The ship was nicknamed Vollidge by her crew.

The ship had one 2-cylinder trunk engine made by John Penn & Sons driving a single 19-foot (5.8 m) propeller. Five rectangular boilers provided steam to the engine at a working pressure of 30 psi (207 kPa; 2 kgf/cm2). The engine produced a total of 4,530 indicated horsepower (3,380 kW) which gave Volage a maximum speed of 15.3 knots (28.3 km/h; 17.6 mph). The ship carried 420 long tons (430 t) of coal, enough to steam 1,850 nautical miles (3,430 km; 2,130 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). Volage was ship rigged and had a sail area of 16,593 square feet (1,542 m2). The lower masts were made of iron, but the other masts were wood. The ship's best speed under sail alone was 13 knots (24 km/h; 15 mph). Her funnel was semi-retractable to reduce wind resistance and her propeller could be hoisted up into the stern of the ship to reduce drag while under sail.

The ship was initially armed with a mix of 7-inch and 64-pounder 64 cwt rifled muzzle-loading guns. The six 7-inch (178 mm) guns and two of the four 64-pounders were mounted on the broadside while the other two were mounted on the forecastle and poop deck as chase guns. The 7-inch guns were replaced in 1873 and the ship was rearmed with a total of eighteen 64-pounders. In 1880, ten BL 6-inch 80-pounder breech-loading guns replaced all the broadside weapons. Two carriages for 14-inch (356 mm) torpedoes were added as well.

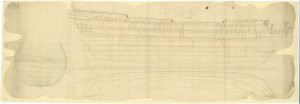

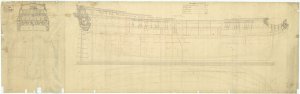

Scale: 1:48. A half block model of the starboard side of the 10-gun single-screw, steam corvette HMS Volage (1869), made entirely in wood and painted in realistic colours. The hull is painted to resemble oxidised coppering below the waterline, and black above. The hull has a clipper bow. Fittings include decorated trail boards, single row of portholes, stump bowsprit, foremast and mainmast, a stump funnel painted ochre, rudder, and stern gallery windows. The propeller and figurehead are currently missing. The model is displayed on a rectangular wooden backboard painted duck-egg blue with frame edges (left-hand edge currently missing). Handwritten on backboard ‘HMS Volage. Built by The Thames Iron Works - Shipbuilding, Engineering & Dry Dock Comp. Blackwall London for Her Britannic Majesty’. On plaque ‘272 Volage corvette - 1869. An iron-built unarmoured ship built at Blackwall served for many years in The Training Squadron. Sold in 1904. Original armament: - 67in and 4 6in M.L. Second armament 18 6in M.L. Final armament 10 6in B.L. and 2 6in M.L. Dimensions Length 270ft Beam 42ft Displacement 3320 Tons Speed 15 knots’. |

Service

HMS Volage was laid down in September 1867 and launched on 27 February 1869. The ship was completed in March 1870 at a total cost of £132,817. Of this, £91,817 was spent on her hull and £41,000 on her machinery. Volage was initially assigned to the Channel Fleet under the command of Captain Sir Michael Culme-Seymour, Bt. However, by the end of 1870, she was transferred to the Flying Squadron which circumnavigated the world. The ship returned to England at the end of 1872 and was given a lengthy refit. Volage recommissioned in 1874 to ferry an expedition of astronomers to the Kerguelen Islands to observe the transit of Venus. She grounded on an uncharted shoal there without damage. The following year, the ship was assigned as the senior officer's ship for the South American side of the South Atlantic. Volage was ordered home in 1879 where she was refitted, rearmed and her boilers were replaced. The ship was assigned to the Training Squadron in the 1880s until it was disbanded in 1899. Volagewas then paid off and sold for scrap on 17 May 1904.

HMS Volage (1869) - Wikipedia